- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: TED LOOS

- Date: SEPTEMBER 27, 2023

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

With a Love Poem and Acid Beat, a Grand Space Feels the Heat

Bucking the rules, and the canon, Jacolby Satterwhite remakes the Met’s Great Hall with his multimedia “A Metta Prayer.” It draws on Titian and video games.

The Metropolitan Museum is giving over its landmark Great Hall to an artist, Jacolby Satterwhite, for the second time. His immersive installation, “A Metta Prayer,” a queer-infused love poem to the universe, set to music and dance, opens Oct. 2. Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

From the soaring Beaux-Arts architecture to the pristine flower arrangements, the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art can be a humbling, even intimidating entry point for visitors.

The artist Jacolby Satterwhite is having none of that. His new Great Hall Commission, “A Metta Prayer,” turns the museum’s solemnity into a funky, queer-infused love poem to the universe, set to an acid house beat.

The installation, made of digital projections and a soundtrack, will be on view through Jan. 7. The piece will feature live performances on weekends in October and November, as well as opening night, Monday, Oct. 2. The video may be the only time Met visitors will hear a benediction like, “May we always keep our wigs on our heads.” Amen.

Satterwhite, 37, was running on adrenaline at the end of August, sitting at his multi-computer command station in his home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Though he is also a painter, much of his recent work is digital, and fantastical moving images are his calling card.

“I haven’t been sleeping,” said the artist, who talks in long, energetic bursts once he gets going. “The grandiosity of the exhibition is a lot of pressure. It’s the first time the Met has done this and they’re breaking a lot of their own rules.”

A metta prayer is a peaceful wish for compassion in the Buddhist tradition, and Satterwhite does transcendental meditation everyday. But he said he has given the practice both a personal spin — “from my Black queer irreverent self” — as well as a generational twist.

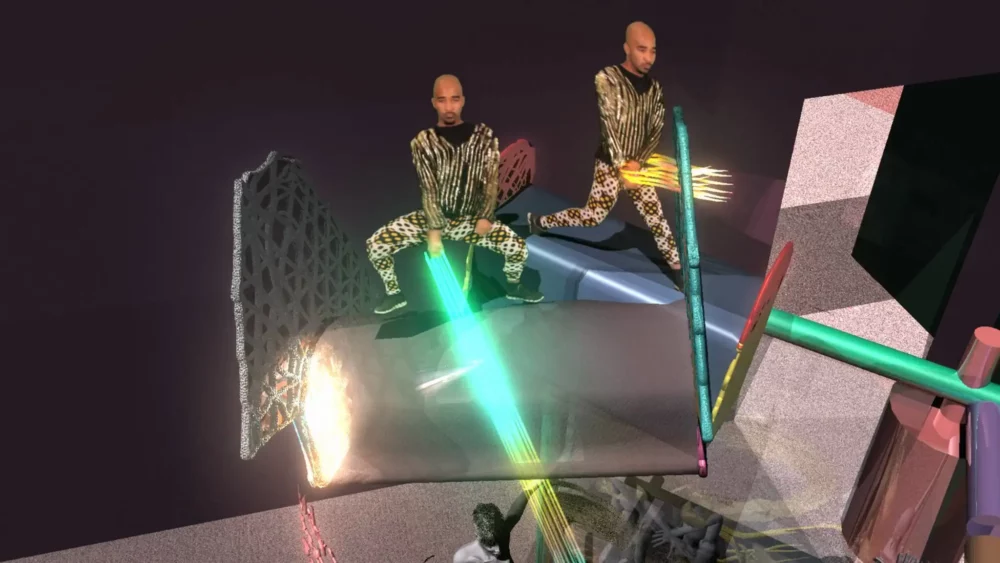

“I’m a millennial who was raised on video games,” Satterwhite said. “I’m using the language, software and engineering that make games — which are meditations on conquest and violence — and turning them upside down to do a love and kindness prayer.”

Satterwhite says he’s using the language, software and engineering of video games “and turning them upside down to do a love and kindness prayer. Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

The video is partly set in New York City, with characters collecting “mantra coins” in the manner of “endless runner” games, in which players navigate obstacles, and partly on a surreal floating cloudscape that Satterwhite said was inspired by Titian’s “Assumption of the Virgin,”

Satterwhite used cutting-edge digital animation techniques to make the work, including motion capture, the same process that helps create the effects in superhero movies. He worked in a space in the Brooklyn Navy Yard scanning dancers (some of the same ones who will perform), the musician Solange Knowles and himself.

The artist also scanned more than 70 objects from different corners of the Met’s collection, from ancient terra-cotta figures to a Noh mask and incorporated them into the work.

He gave particular attention to arms like a medieval dagger-axe. “I’m integrating artworks that were made for imperialist conquest,” he said. “But I’m bringing them into my world.”

“I really respect the canon,” he said of the Met’s encyclopedic collection. “I just don’t take it too seriously.”

The six-channel video will be projected onto four main walls of the Great Hall and two large lunettes on the balcony level — and a separate light projection will surround the space’s three skylight domes.

Satterwhite is changing the color of the screens of the electronic ticket kiosks to match his work, and he is even adjusting the palette of the Met’s famed floral arrangements — the first time an artist has been allowed to tinker with the fruits of Lila Acheson Wallace’s endowment.

The Great Hall interior, designed by the architect Richard Morris Hunt— who also did the building’s Fifth Avenue facade — is a New York City landmark and the projectors can only be placed in certain spots. (The first official Great Hall Commission, two paintings by the Canadian artist Kent Monkman, had a more conventional installation in 2019.)

“There are a lot of restrictions about what we can and can’t do,” said Lauren Rosati, an associate curator in the Met’s department of modern and contemporary art. Because of the video projections, Rosati noted, “Nighttime viewing will get closest to the artist’s intent.”

Limor Tomer, the general manager of the Met’s Live Arts program, emphasized that the Met wanted a certain feeling of disruption with “Metta Prayer,” but it could only go so far, given the high traffic.

The opening night performance will also feature some brand-new things for the 153-year-old museum. Satterwhite will be playing the synthesizer and a beat machine, and doing vocals. “I’ll have backup singers, a cellist, a wrestler on each side doing evangelical rituals, throwing holy water around,” he added.

Satterwhite is coming off a very busy five-year streak of being featured in exhibitions at museums all over the world and, last fall, unveiling a commissioned piece for Lincoln Center’s new David Geffen Hall.

His digital work there, “An Eclectic Dance to the Music of Time,” achieved, in the words of a New York Times critic, “an extraordinary balance between stasis and movement, picture and narrative, the excitement of the present and the grandeur of history.”

He usually works solo, on his computers — though he had help with the scanning process from a couple of assistants on “Metta Prayer.”

“An Eclectic Dance to the Music of Time” by Jacolby Satterwhite at David Geffen Hall. Caitlin Ochs for The New York Times

“It’s amazing to me that he does it all himself,” said Max Hollein, the Met’s director and chief executive, who has made it his mission to ramp up the museum’s involvement in contemporary art with such projects.

For Satterwhite, self-reliance was born of challenges. He grew up in Columbia, S.C. “I had bone cancer as a child,” he said. “I had cancer twice, actually. I have a prosthetic shoulder and a metal arm.”

The experience may help explain his furious pace now. “It defined the urgency of making art to have something to leave behind,” he said.

The artist was close with his mother, Patricia Satterwhite, who died in 2016, and she now serves as a posthumous collaborator. She was a self-taught artist who did thousands of drawings and also wrote and performed songs. A remixed version of her singing can be heard in the “Metta Prayer” soundtrack, just one of the ways her work has been integrated in his art over the years.

Satterwhite is frank about challenges he has faced as an adult, including past struggles with addiction. But they have not stopped his career. He got his B.F.A. from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore and his M.F.A. from the University of Pennsylvania. He was only in his late 20s when he had a piece in the 2014 Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art, an installment of his “Reifying Desire” video series. As in “Metta Prayer,” a digital avatar navigates a fantasy space and performs there, and the piece included elements from his mother’s drawings.

Still from Jacolby Satterwhite’s digital video, “Reifying Desire 5” (2013), in which a digital avatar navigates a fantasy space and performs there, via Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Derrick Adams, the New York based multidisciplinary artist who taught the younger artist in his undergraduate years, said that for Satterwhite, “Emotional transparency becomes part of the art itself.”

He recalled that Satterwhite’s enthusiasm was not lost on anyone in the classroom. “I used to tell him, ‘Do you want to teach my class?’” Adams said, laughing. “He was always telling the students what artists to look at. He was giving them lists.”

Adams said that Satterwhite’s mastery of technology may sometimes obscure an old-school emotional current in the work.

“It has a raw feeling from the ’70s and ’80s,” Adams said, comparing him to Keith Haring. “If Jacolby had been around then, he’d be wheat-pasting all over town, too.”

And despite the high-energy of much of “Metta Prayer,” it has a somber note, too, because of the murder of the dancer and choreographer O’Shae Sibley, who was killed at a Brooklyn gas station in July. Sibley, whom the police said was subjected to homophobic slurs during the incident, is one of the performers seen dancing in the Met work.

“It was triggering,” Satterwhite said. “He got killed for vogueing in front of a gas station.”

The murder underlines the high emotional stakes of creating and self-expression, depending on who is doing the expressing. “In a way, it brings together everything I’m thinking about,” Satterwhite said. And it seems to be another example of his turning vulnerability into art.

When the Met approached him originally for the commission, Satterwhite said his response was, “Of course! I’ll do anything. There’s nothing that can scare me at this point.”