Coercive Beliefs

BY MATT KENNY

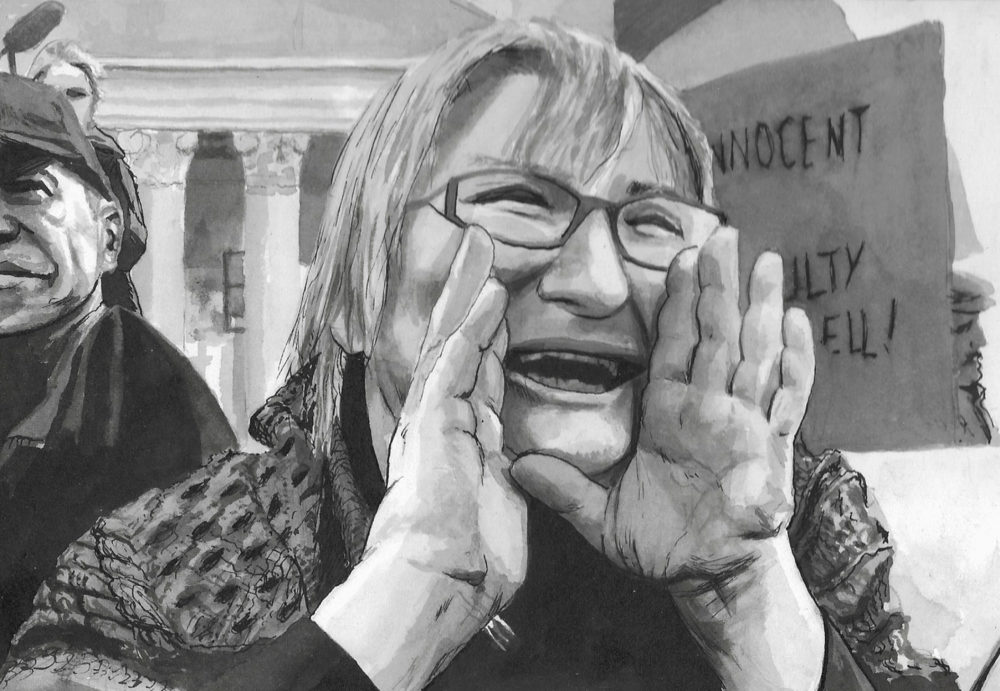

1. Lynne Stewart, Present

Fig. 1

The Advocate

On March 7, 2017,

less than four weeks after

the Blind Sheikh died,

Lynne Stewart, his former lawyer,

passed away after a long struggle with breast cancer

at seventy-seven years old.

Before she died

Stewart reflected on Omar Abdel-Rahman to the New York Times:

“he was the personification of an American hero.

I feel very strongly that he suffered.

He suffered unjustly because

he was convicted of a bogus crime.”

On January 17, 1996,

Abdel-Rahman was sentenced to life in prison

for seditious conspiracy against the United States.

At the center of the indictment was the “Day of Terror” plot,

in which followers of the Blind Sheikh were accused

of planning to detonate five bombs

in the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels

the George Washington Bridge,

the United Nations Headquarters,

and a federal office building in lower Manhattan.

These charges

included the conspiracy to bomb the World Trade Center

on February 26, 1993.

Following the sentencing,

Abdel-Rahman proclaimed his innocence,

declaring the trial as

“not only an attack on Muslims alone,

but it is an attack on the words of God.

I have not committed any crime except

telling people about Islam.”

Violence seemed to follow the Sheikh wherever he went.

In Egypt,

the Sheikh had been accused

of inciting two major riots and issuing the fatwa

that led to the assassination of President Anwar Sadat.

In the United States,

Abdel-Rahman

found himself in close proximity

to the deaths

of Afghan mujahideen fundraiser Mustafa Shalabi

and the American-Israeli hate activist Meir Kahane.

It was the word of Omar Abdel-Rahman

that touched this history of violence.

Abdel-Rahman was the spiritual guide of

al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya,

a revolutionary movement

dedicated to overthrowing the secular Egyptian government

and replacing it with an Islamic state.

Nearly a decade after Abdel-Rahman’s sentencing,

on February 10, 2005,

Lynne Stewart

was convicted,

alongside the Abdel-Rahman legal team’s

translator, Mohammed Yousry,

and al-Gama’a middleman Ahmed Abdel Sattar,

for providing material support to terrorists.

Stewart was accused of passing messages

from the Blind Sheikh to supporters in Egypt

while he was under Special Administrative Measures.

SAMs are directives

the United States Attorney General

may issue the United States Bureau of Prisons

“regarding housing, correspondence and visitors to specific inmates.”

It includes prisoners awaiting trial or being tried,

as well as those convicted,

when it is alleged

there is a

“substantial risk that a prisoner’s communications

or contacts with persons

could result in death or serious bodily injury to persons, or substantial damage to property

that would entail the risk

of death or serious bodily injury to persons.”

Stewart had signed agreements

to these procedures under both the Clinton and Bush

administrations.

As the spiritual guide to al-Gama’a,

Abdel-Rahman’s communications with the outside world were absolutely restricted.

The only weapon Abdel-Rahman ever had at his disposal was his ability to communicate his vision

with the authority vested in him by his followers.

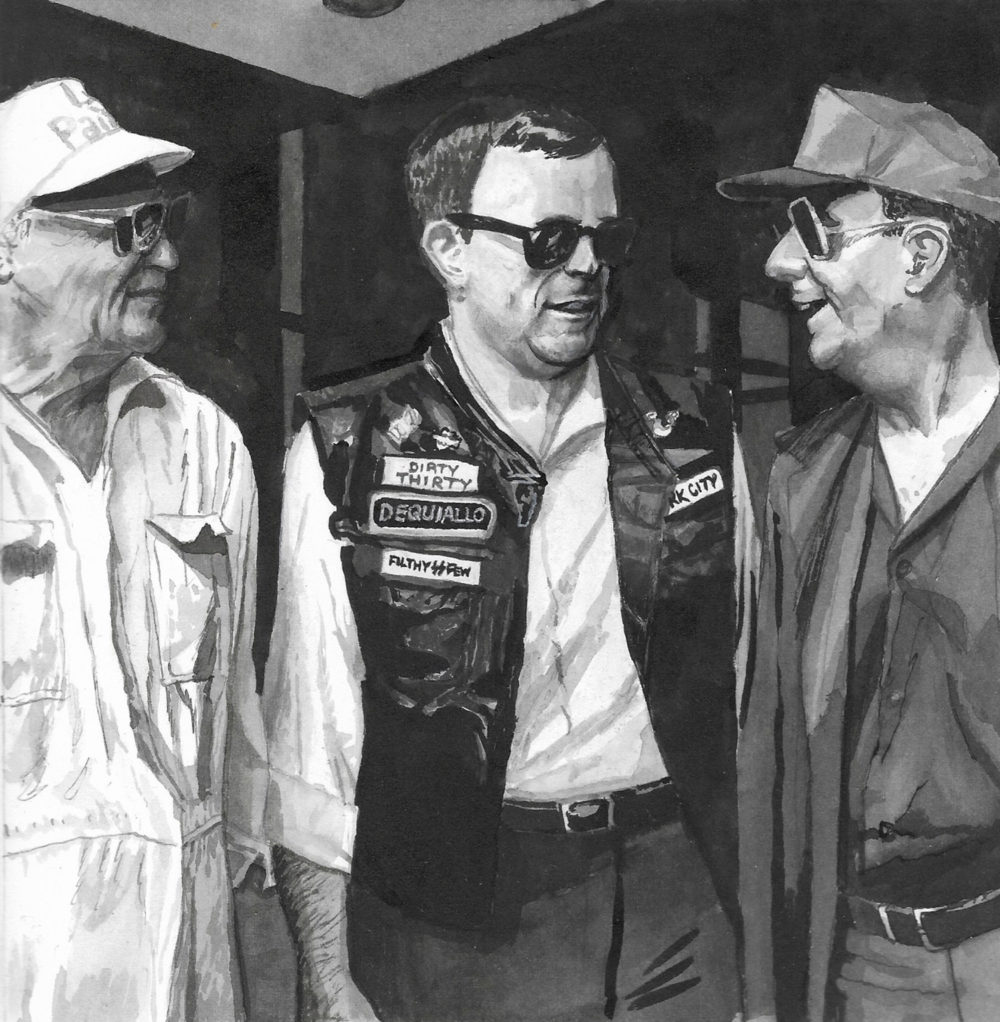

Fig. 2

Twice

Stewart had spoken to a reporter who worked for Reuters in Cairo regarding Abdel-Rahman’s view

that al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya withdraw

from a cease-fire agreement with the Egyptian Government.

On April 9, 2002,

Attorney General John Ashcroft announced in New York City

that the Federal Government was indicting

Stewart, Yousry, and Sattar

for materially aiding a terrorist organization,

conspiracy to provide material aid to a terrorist organization,

defrauding the US Government,

and lying to the US Government

under the 1996 Terrorism Act.

Stewart was arrested in front of her home

and brought to Manhattan’s FBI office

while her office was searched.

Three hours later she was locked up.

That night the Attorney General

went on the David Letterman Show

to tie Stewart’s case to the War on Terror.

His remarks were met with applause.

Letterman wanted him to sing a song.

Stewart’s supporters posted the $500,000 bail.

On June 13, 2003,

Judge John Koeltl asked prosecutor Christopher Morvillo

what distinguished political activities protected

by the United States Constitution

from criminal conduct in terrorism cases.

His answer was simply,

“You know it when you see it, your honor.”

The indictment included the revelation

that Stewart’s meetings with the Blind Sheikh in prison

had been recorded for two years before her arrest.

The explosive potential of this intrusion

into attorney–client privileges

meant that this trial could reframe what it meant for lawyers

to defend unpopular clients.

The duel between Stewart and Ashcrof

t

had massive ramifications for civil liberties in the United States

and the chilling message from the government

was that the attacks on 9/11

had deeply altered America’s legal system.

Together, Stewart and the Justice Department

were pioneering new boundaries

in the freshly born “war on terror.”

The scale of these questions

was not lost on the judge overseeing the case.

On July 22, 2003,

Judge Koeltl issued a seventy-seven-page opinion that

“the statute under which the charges were brought,”

the 1996 Terrorism Act, was

“unconstitutionally vague as applied

to the defendants’ conduct”

and dismissed the charges.

In response,

an angry and embarrassed Attorney General Ashcroft,

along with James B. Comey,

US Attorney of the Southern District of New York,

announced superseding charges against

Ahmed Abdel Sattar, Lynne Stewart, and Mohammed Yousry

on November 19, 2003.

The indictment read that

“after Abdel Rahman’s arrest,

a coalition of terrorists, supporters, and followers,

including leaders and associates

of the Islamic Group, al Qaeda, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad,

and the Abu Sayyaf terrorist group in the Philippines,

threatened and committed acts of terrorism

directed at obtaining the release

of Abdel Rahman from prison.”

The indictment continued,

“Abdel Rahman himself urged his followers

to wage jihad to obtain his release from custody.

For instance, in a message to his followers

recorded while he was in prison,

Abdel Rahman stated that

“It is a duty upon all the Muslims around the world

to come to free the Sheikh,

and to rescue him from this jail.”

New charges were added against Sattar,

alleging that with Abdel Rahman,

Sattar conspired to kill and kidnap persons in a foreign country.

Stewart and Yousry were charged with

“providing and concealing material support

to conceal and kidnap persons in a foreign country.”

The government wanted Stewart badly.

At the opening of the new trial in June 2004,

prosecutor Morvillo told the jury that Stewart

“used her status as a lawyer as a cloak

to smuggle messages into and out of prison.”

He charged that Stewart allowed the Blind Sheikh

“to incite terrorism.”

The prosecution showed the jury

video of Osama bin Laden

urging support for the Blind Sheikh.

On February 10, 2005,

Stewart, Yousry, and Sattar were convicted

after the jury deliberated for thirteen days.

The prosecution hoped that Stewart

would spend the remainder of her life in prison:

“…this sentence of 30 years

will not only punish Stewart for her actions,

but serve as a deterrent for other lawyers

who believe that they are above

the rules and regulations of penal institutions

or otherwise try to skirt the laws of this country.”

Stewart was shocked by the prosecution’s proposed sentencing;

she had signed agreements and knowingly broken them,

expecting a different punishment.

“It said on this piece of paper that breaking the S.A.M.s

could result in being cut off from visits.”

On October 16, 2006, Stewart was sentenced

to twenty-eight months in prison by Judge John Koeltl.

The sentence was viewed by the administration

as a frustrating setback.

Stewart was automatically disbarred.

She appealed the court’s decision and

on November 17, 2009,

the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

not only upheld the conviction

but also ordered that she be re-sentenced.

Once again, she returned to Judge Koeltl’s court

but this time the judge was ordered

to take

“terrorism, perjury and abuse of her position as a lawyer”

into account in his decision on sentencing.

On July 15, 2010

Lynne Stewart,

seventy years old,

mother and grandmother,

was sentenced to one-hundred-twenty months in prison

by Judge Koeltl.

Numerous accounts

mention

a

split-second of silence in the court the moment the words

“one hundred twenty months,”

left the judge’s mouth.

That silence was

devoted to converting

those months to years.

Ten.

Five times the original sentence.

“A death sentence,”

said her husband, Ralph Poynter. The New York Times reported that

“a collective gasp went up from Ms. Stewart’s supporters,

who packed the broad high-ceilinged courtroom.

That was followed by a few shrieks and sobs;

some held their hands over their mouths.”

When asked to speak, Stewart answered,

“I’m somewhat stunned, judge,

by the swift change in my outlook.”

Regaining composure, Stewart lamented,

“I feel like I let a lot of my good people down.”

Friends, family, and supporters shouted:

“We love you!”

Stewart’s breast cancer,

originally diagnosed in 2006,

returned while she was in prison.

In early 2013 Stewart received chemotherapy in shackles.

Diagnosed with only eighteen months to live,

Stewart was granted a compassionate release

and left prison on December 31, 2013.

Aboveground and Underground

Stewart was a passionate “movement” lawyer.

Born and raised in Queens,

Stewart went to law school after her political awakening.

Stewart’s practice brought her into the company

of a group of powerful activist lawyers

facing the twilight of the revolutionary movements of the 1960s.

In 1962,

Stewart was a librarian at a public school in Harlem,

where she met her future husband, Ralph Poynter,

a black teacher and union organizer.

A sheltered white woman from Queens,

what Stewart witnessed in Harlem

was not only the school’s deep inadequacy,

but American society’s systemic oppression of African Americans.

Poynter brought Stewart into the flourishing movement

for civil rights and

over the course of four decades Poynter and Stewart

would become the dynamic duo of New York’s activist community.

Early on,

their activities came at a cost:

Poynter was fired for trying to organize parents

to confront the collapsing school system.

Afterward, Stewart and Poynter became central figures

in New York City’s revolutionary underground.

In 1971,

Stewart went to law school with an eye toward advocacy.

“Because I could come up against government,

fight government

on behalf of someone who didn’t really have the tools

or the wherewithal to do that

and yet I could still go home

and look at myself in the mirror.”

Poynter and Stewart spoke

of “aboveground” activism and the “underground” militancy

and it was the underground that came to define Stewart’s service.

Stewart described her beliefs in these terms:

“We said, if we can’t have the apples off of the tree,

we’ll chop the damn tree down.”

Every profile of Stewart

makes note of her personal warmth,

her gift for reaching the sympathies of a jury,

and her moral passion.

Her appearance was so unpretentious

it amounted to a form of reverse-pretention.

Stewart’s adversaries respected her

and her clients loved her.

These clients included

former Weatherman David Gilbert,

mob enforcer Sammy “the Bull” Gravano,

Colin Ferguson, the Long Island Railroad Shooter,

and Black Panther airline hijacker Willie Roger Holder.

Willie Holder’s hijacking of Western Airlines flight 701

still holds the record

for the longest-distance hijacking in American history,

flying from Los Angeles to San Francisco to New York to Algeria.

Whether they were black power activists or gangsters,

Stewart zealously fought for them.

Tributes to Stewart from former clients and activists

following her death

reveal the respect she earned.

Mumia Abu-Jamal, an activist and journalist

serving life in prison

for the murder of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner:

“For decades, she and her husband, Ralph, fought for

New York City’s political activists and revolutionaries, like the

Black Panthers and Young Lords—a Puerto Rican socialist collective.

But mostly, they fought for the freedom of the poor and dispossessed

of New York’s Black and Brown ghettoes.”

Jaan Laaman, member of the Ohio 7,

in prison serving a fifty-three-year sentence:

“For decades Lynne Stewart was a, if not the,

preeminent human rights, civil rights, peoples’ lawyer,

boldly fighting for justice, equality, and freedom

in many of the most important and widely reported cases in the United States.”

As antagonistic as Stewart was to “the system,”

she also believed that her role as an advocate

could change that system.

In a fascinating interview with Chris Hedges in the summer of 2016

about the deterioration of radical activism,

Stewart and Poynter

looked back on their sixty years of resistance.

Poynter and Hedges shared

a dark view of America’s future prospects.

Speculating on the result of America’s

ambivalent treatment of its disenfranchised people,

Poynter asserted that

“there is going to be death”

in the country’s inevitable turn toward revolution.

In their view it was unlikely

that American society had the ability to change course,

short of a massive violent uprising.

In the face of bleak evidence,

rising homicides in Chicago,

the militarization of the police,

the water crisis in Flint, Michigan,

the explosion of income inequality,

radical movements “defanged”

by a system

designed to seduce and oppress with startling completeness,

Poynter and Hedges had some justification for their pessimism.

Stewart stepped in,

even after more than four years in prison,

with a somewhat more hopeful outlook.

“I just want to end by saying that you know,

I do have high hopes, never ever giving up

because as someone once said to me in Berkley of all places,

they said you know, Lynne,

when we were in the fifties and we were out there

trying to get people signing petitions for the Rosenbergs

and they executed them

we really thought this is never going to change.

And then we had the sixties.

So I feel the same way.

I look at it now and I say, can this ever change,

are we so caught up in this,

is this so much YouTube

and so little people actually communicating,

will it change?

And I have faith, it will change.

And it will come about the way it always does,

by people who are just fed up

and go out there and say I am going to fight for this,

fight for this because we are also,

as Ralph has just finished saying,

that it’s going to come by being nice and playing nice.

It’s never going to come that way.”

Stewart’s vantage point

from her start

in the battle for civil rights,

the struggle against the Vietnam War,

to her professional arrival at

the withering of counterculture,

the explosion of the drug wars,

and finally her swan song in the midst of the War on Terrorism

made her witness to America’s darker currents.

She spoke to the National Lawyers Guild in 2003,

presenting her view of advocacy:

“For we have formidable enemies

not unlike those in the tales of the ancient days.

There is consummate evil

that unleashes its dogs of war on the helpless;

an enemy motivated only by insatiable greed—

The Miller’s daughter made to spin gold—

the fisherman’s wife:

Midas,

all with no thought of consequences.

In this enemy

there is no love of the land

or the creatures that live there, no compassion for the people.

This enemy will destroy the air we breathe

and the water we drink

as long as the dollars keep filling up their money boxes.

We now resume our everyday lives

but we have been charged once again,

with, and for, our quests,

and like Hippolyta and her Amazons;

like David going forth to meet Goliath,

like Beowulf the dragon slayer,

like Quenn Zenobia,

who made war on the Romans,

like Sir Galahad seeking the holy grail.

And modern heroes, dare I mention?

Ho and Mao and Lenin,

Fidel and Nelson Mandela and John Brown,

Che Guevara who reminds us

‘At the risk of sounding ridiculous,

let me say that the true revolutionary

is guided by a great feeling of love.’

Our quests, like theirs,

are to shake the very foundations of the continents.

We go out to stop police brutality—

To rescue the imprisoned—

To change the rules for those who have never been able

to get to the starting line much less run the race,

because of color, physical condition,

gender, mental impairment.

We go forth to preserve

the air and land and water and sky and all the beasts

that crawl and fly.

We go forth to safeguard

the right to speak and write,

to join; to learn,

to rest safe at home, to be secure, fed, healthy, sheltered,

loved and loving,

to be at peace with one’s identity.”

When asked by Abdel-Rahman’s lawyer and

former Attorney General Ramsey Clark

to take the Blind Sheikh’s case

he told her,

“If you are a fireman and you walk by a fire

you must run in.”

Fig. 3

“Something of a Folk Hero”

Before Omar Abdel-Rahman,

Lynne Stewart’s most famous legal battle was securing,

alongside infamous defense attorney William M. Kunstler,

the 1988 acquittal of Larry Davis,

a twenty-two-year-old black man,

for the attempted murder of nine police officers in 1986.

On November 19, 1986,

twenty-seven police officers surrounded

a Bronx building.

This was a year after

the New York Times, a little late to the story, first reported that a

“new form of cocaine, known as crack,

was on sale in New York City.”

These twenty-seven police officers assembled

outside of a home

with bulletproof vests, shotguns, and handguns.

Their purpose of the raid was

to question twenty-year-old Larry Davis.

Twenty days earlier

Davis was apparently a suspect

in an exchange of gunfire and subsequent car chase

with the police in the High Bridge section of the Bronx.

There was no arrest warrant for the raid.

The intercom broken, a tenant let the heavily armed squad in.

Fifteen officers took up positions outside the six-story tenement,

Twelve others went inside

Robert McFadden recounted the raid vividly

in the New York Times the following day:

“Six of these—

a captain, a sergeant, two detectives,

and two emergency service officers—

entered the three-room ground floor apartment

of the suspect’s sister, Regina Lewis.

Four adults and four children,

including Mr. Davis and his girlfriend

and infant daughter were in the apartment.

‘I heard a knock,’ Ms. Lewis recalled yesterday, ‘I was on the phone near the doorway.

I saw the knob turning and I

thought it was my sister.’”

She opened the door, the police entered with guns drawn

and told Davis’s sister and girlfriend

to take the children out of the apartment.

They shouted:

“‘Come out, Larry, you don’t have a chance—

we’ve got you surrounded.’

Blazing away with a shotgun and handguns

from a small bedroom where two babies lay asleep,

Mr. Davis wounded the six officers

as they stood in an adjoining living room.

Returning the gunfire in a shootout

in which 30 shots and eight shotgun blasts resounded,

the six retreated into a hallway.

In the ensuing confusion of bleeding officers,

screaming bystanders and gunfire,

the police,

who took cover behind a stairwell

and a corner of an L-shaped hallway,

apparently took their eyes off the door to the apartment

where Mr. Davis was hiding.

Slipping out of his cul-de-sac,

the gunman entered the hallway,

went into a next-door apartment

whose lock had been shot off in the gunplay,

dropped 10 feet from a window into a rear courtyard,

vaulted a brick fence into an alley

and escaped unnoticed.

As the wounded officers were rushed

to Bronx-Lebanon Hospital

across the street,

a search of the 30-family building

and the surrounding area was conducted,

but no trace of the suspect was found.

In the apartment police found a 16-gauge shotgun,

a .32-caliber pistol and a .357 Magnum pistol.”

Humiliated, the NYPD deployed a bloodhound to search for Davis.

“Tunnels, bridges, airports and rail and bus terminals

were being watched

and a task force of heavily armed officers

wearing bulletproof vests

searched for known haunts of the fugitive…

It was the highest number of officers

shot in a single incident in memory.”

In the aftermath, it was revealed

that Davis was wanted for the murder of five men.

After a citywide manhunt lasting seventeen days,

police finally caught up with Davis

in the Twin Parks housing project.

Davis held a woman and her two children hostage.

The police learned this at one in the morning

and for the next six hours

they negotiated from an apartment

just down the hall

from Davis and his hostages.

At the start, Davis,

panicked, proclaimed he had removed the pin from a grenade,

but a long conversation about synthesizers with a savvy police officer

defused the tension.

At seven in the morning Davis surrendered,

escorted through the project hallways to cheers and clapping.

“Lar-ry! Lar-ry!”

“As police searched him, they found one pocket full of loose

change and another with seven or eight pieces of candy, which

fell to the ground.”

“Everybody grabbed for the candy,” said Ms. Arroyo, whose

family was never forced to flee the apartment. “I grabbed a

Tootsie Roll from the floor and put it in my pocket. A lot of

people grabbed them as souvenirs.”

Larry Davis had become a folk hero.

Fig. 4

A Social Pharmacology of Smokable Cocaine

Only two and a half months prior,

on September 14, 1986,

President Reagan and the first lady

went on national television

to talk about cocaine.

The American landscape was faced with an array of challenges,

untouched by the artificial glow of the President’s sunny rhetoric,

and alongside his wife he sought to address one of them:

the War on Drugs.

Included in this paternal address

was a reminiscence of the glory days of World War II, America’s greatest hour:

“My generation will remember

how America swung into action

when we were attacked in World War II.

The war was not just fought

by the fellows flying the planes

or driving the tanks.

It was fought at home by a mobilized nation—

men and women alike—

building planes and ships,

clothing sailors and soldiers

feeding marines and airmen;

and it was fought by children

planting victory gardens and collecting cans.”

The President went on,

speculating about the dead of the Second World War:

“Never would they see another sunlit day glistening

off a lake or river back home

or

miles of corn pushing up against the open sky of our plains. The pristine air of our mountains

and the driving energy of our cities are theirs no more.”

On December 20, 1985,

the Associated Press published a report

by Brian Barger and Robert Parry

alleging that that Nicaraguan rebels in northern Costa Rica

were trafficking cocaine to finance their war

against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

The report accused

the Nicaraguan Democratic Force,

M-3,

and the Revolutionary Democratic Alliance

of using drug money to finance the war against the communists.

At the same time these groups were also

financed and supported by a secret operation

run out of Reagan’s National Security Council.

Five of the whistleblowers talking

to Barger and Parry were American mercenaries

who went down to Costa Rica to train the Contras.

Witnesses at the front in Central America

were in mortal danger.

Former Panamanian Health Minister Hugo Spadafora

was decapitated and stuffed into a US Mail bag

and dumped

near the Costa Rica–Panama border.

The figure “F-8” was carved into his corpse;

the signature of a Panamanian hit squad.

Spadafora was murdered only days after talking to

a DEA official in the American Embassy in Costa Rica

about blowing the whistle

on corruption and cocaine in the Contra movement.

The Contras were a diverse coalition

of counterrevolutionary Nicaraguans

fighting the Sandinistas,

the leftist guerilla movement that assumed power

after the fall of the Somoza Dynasty.

Still stricken with Vietnam syndrome,

the United States remained allergic to military adventurism,

so the United States assumed the role of wealthy patron

for freedom fighters from Honduras to Afghanistan.

The soldiers in Reagan’s

global war against communism were not the American GIs

he so wistfully romanticized in his speech.

Reagan’s crusade against communism

would be a war run by intelligence officers and waged by proxies.

The foot soldiers in this effort were

fundraisers, spies, weekend warriors, public relations firms,

mercenaries, death squads, freedom fighters, holy warriors,

and drug traffickers.

The Contras’ abysmal human rights record and

an ill-conceived CIA operation that planted mines

in Nicaragua’s harbors

drove Congress to write the Bolan Amendment,

as part of a Defense Appropriations Bill,

which was signed into law by Reagan

on December 21, 1982.

The Boland Amendment strictly prohibited intelligence agencies

from providing military support

to groups for the purpose

of overthrowing the Government of Nicaragua.

When Congress cut off financing to Contras,

the White House chose to develop

off-the-books pipelines to support the Contras

and arms deals to the Iranians in exchange for hostages.

The Reagan White House’s attempts

to kill two birds with one stone

blossomed into a massive autonomous, interconnected covert war

that stretched from Afghanistan to Iran to Nicaragua.

Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Israel,

Panama, Argentina, Egypt, and Pakistan

were just a few of the nations woven into this “secret war.”

The fact that this war was completely privatized

meant that the players,

friends of the White House,

were getting rich off of airlines to fly weapons,

finder’s fees to facilitate arms deals,

and paramilitary training to rebels.

All of this money was made

in the pursuit of the Reagan White House’s policy objectives.

The chief operations officer of these pipelines

was a young National Security Council staffer and Marine

named Oliver North,

who looked like he walked straight out of central casting

for “American Hero.”

Bearing a sycophant’s gift for opportunism and social climbing,

young Oliver North found himself in the center

of what would become the largest political scandal since Watergate.

Wearing his Marine uniform,

North basked in the ire of Congress.

North, who knew how to play to a camera,

managed to keep a brave face.

Since 1982

drug traffickers

had been a reliably opportunistic ally

in the Reagan Administration’s secret war

against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

Drug networks,

professional keepers of secret pipelines,

were all too happy to offer their services

to score chips to cash when they needed them.

Veteran pilots highly skilled at evading US border security

would later tell Congressional committees

about how they were supplied unwatched corridors

back into the States.

The pilots testified that they assumed they worked for the CIA.

As reports of these arrangements began to appear in the media,

Oliver North started paying good money

to spy on journalists and discredit their sources

talking about the White House’s secret war.

Brian Barger and Robert Parry’s reporting was

an explicit threat to North’s enterprise.

Jack Terrell was a militant anticommunist member

of a mercenary group

called Civilian Military Assistance,

who went to Central America to fight the Sandinistas.

Jack Terrell was one of Brian Barger

and Robert Parry’s primary sources

on the Contra/cocaine story.

Terrell told Barger and Parry that

he saw Contras commit

mass executions, arbitrarily murder civilians, and run drugs,

and he was ready to tell his story in Washington.

By this time, Oliver North

paid a former CIA agent

$4,000 a month

to smear opponents of the administration’s foreign policy.

Jack Terrell was one of this agent’s primary targets.

Glenn Robinette, North’s private security officer,

wined and dined Terrell hoping to keep him from Congress.

Terrell didn’t take the bait.

It didn’t matter,

the White House had

other levers on the whistleblower:

Terrell’s phones were tapped.

Apparently, Terrell said he could

“get the president”

over the phone and before long

the Terrorist Incident Working Group,

North’s own “security apparatus,”

was supplying the FBI with a report on Terrell,

while airplanes serving his arms pipeline

flew cocaine into the United States.

“America has accomplished so much

in these last few years,

whether it’s been rebuilding our economy

or serving the cause of freedom around the world. What we’ve been able to achieve

has been done with your help—

with us working together as a nation united. Now we need your support again.”

In the president and first lady’s unique joint address from the West Hall of the White House

Nancy and Ronnie spoke from a sofa,

the nation gathered before kindly grandparents.

“Drugs are menacing our society.

They’re threatening our values and undercutting our institutions.

They’re killing our children….

Despite our best efforts,

illegal cocaine is coming into our country

at alarming levels and four to five million people regularly use it.

Five hundred thousand Americans are hooked on heroin.

One in twelve persons smokes marijuana regularly.

Regular drug use is even higher

among the age group eighteen to twenty-five—

most likely just entering the workforce.

Today there’s a new epidemic: smokable cocaine, otherwise known as crack.

It is an explosively destructive and often lethal substance which is crushing its users.

It is an uncontrolled fire.”

The camera turned to the first lady,

poised, eyes tracking the text she is to read.

“As a mother,

I’ve always thought of September as a special month,

a time when we bundled our children off to school,

to the warmth of an environment in which they could

fulfill the promise and hope in those restless minds.

But so much has happened over these last years,

so much to shake the foundations of all that we know

and all that we believe in.

Today there’s a drug and alcohol abuse epidemic

in this country,

and no one is safe from it—

not you, not me,

and certainly not our children,

because this epidemic has their names written on it….

Our job is never easy

because drug criminals are ingenious.

They work every day to plot a new and better

way to steal our children’s lives,

just as they’ve done by developing this new drug, crack.

For every door that we close, they open a new door to death.”

On July 26, 1986,

Oliver North wrote a memo to the National Security Council entitled

“Terrorist Threat: Terrell.”

In addition to allegedly threatening the president’s life,

“Terrell has appeared on various television ‘documentaries’ alleging corruption,

human rights abuses,

drug running,

arms smuggling

and assassination

attempts by the resistance and their supporters.

Terrell is also believed to be involved with various

congressional staffs in preparing for hearings and inquiries

regarding the role of U.S. Government officials

in illegally supporting the Nicaraguan resistance.”

Ronald Reagan read the memo about Terrell.

In the middle of August

Terrell took two days of polygraph examinations

conducted by the FBI and the Secret Service

to determine if he was a threat to the president.

Terrell was never charged with a crime.

One of Terrell’s media contacts,

Brian Barger, called the police

when he realized his home was being watched. The police learned that

two individuals rented an apartment across the street and monitored the journalist’s home.

By the time Ronnie and Nancy

gave their cocaine speech from the White House,

his Justice Department’s criminal division

was stonewalling

Senators John Kerry, Richard Lugar, and Claiborne Pell’s

requests

“for information on more than two dozen names

of individuals connected to the contra operation

and suspected of drug trafficking.”

There was some soul searching

in the Justice Department on the issue:

“I must confess I was concerned.

I was concerned not so much that

there were going to be hearings

[about contra-connected drug trafficking].

I was concerned that we were not responding

to what was obviously a legitimate congressional request.

We were not refusing to respond in giving explanations

or justifications for it.

We were seemingly just stonewalling

what was a continuing barrage of requests for information.

That concerned me to no end.”

After Nancy finished offering her solution

to the degradation of the United States of America

by drugs and alcohol

the camera turned to the president.

“In this crusade, let us not forget who we are.

Drug abuse is a repudiation of everything America is.

The destructiveness

and human wreckage

mock our heritage.

Think for a moment how special it is to be an American.

Can we doubt that

only a divine providence placed this land,

this island of freedom,

here as a refuge for all those people on the world

who yearn to breathe free.”

Buy Crack

On July 9, 1986,

United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York,

Rudy Giuliani,

Ben Baer, the Chairman of the Federal Parole Commission,

and New York Senator Alfonse D’Amato

dressed up like “drug addicts” to go buy some crack.

Giuliani wore sunglasses and a Hells Angels vest.

D’amato wore a ball cap and windbreaker.

Baer wore a clean white painter’s outfit.

Agents from the Manhattan office of the DEA

drove them separately uptown to 555 West 160th Street playing

“rock music loudly.”

Baer rolled up in a car

with out-of-state plates and nearly got charged

an out-of-towner’s rate of $40.

Baer played the elderly “crack-head” for the dealer.

Baer claimed he bargained the man down to $15.

The story goes

that Giuliani and D’Amato each bought two vials of crack for $20.

Baer managed to get his two vials for $15.

This gesture of cultural tourism

was a publicity stunt for the campaign to re-elect Senator D’Amato

and was organized by local DEA agent Robert Stutman.

Seemingly the only one really enjoying himself,

Giuliani was the most ridiculous looking of the three tourists.

“We need emergency action,”

he announced blandly,

touching his vest.

This anthropological expedition

sought to prove that New York City

had what amounted to an open-air drug market.

D’Amato was hawking a crime bill in the senate

calling for mandatory prison terms without parole for crack dealers

“30 heavily armed drug enforcement agents

and undercover police officers

stood ready to move in

if the expedition took a violent turn”

The crack was phony.

Arrests were promised.

Fig. 5

Staging

The Bronx, Manhattan, and Long Island District Attorney’s office

presented a heady series of charges against Larry Davis.

The murder of four drug dealers,

attempted murder of nine police officers,

kidnapping,

automobile theft,

and weapons possession.

On November 20, 1988,

Davis was acquitted of the attempted murder of nine police officers.

The jury also acquitted Davis

of six counts of aggravated assault

in the wounding of six of the officers.

He was convicted of six counts of criminal possession of a weapon.

The District Attorney is described as having slumped into his chair staring straight ahead

as “not guilty” was said fourteen times.

William Kunstler and Lynne Stewart convinced the jury

that the police raid was

“staged to mask an attempt to assassinate Mr. Davis

for his knowledge of police drug corruption”

and that he

“quite properly fired in self-defense.”

In three trials over the course of two years

only the weapons possession charges stuck to Larry Davis.

The humiliation of the DA’s office was in large part

due to Kunstler and Stewart’s genius as defense attorneys.

In the trial for the murders of the four drug dealers

Kunstler and Stewart successfully argued

that Davis was being framed

by the police

in order to justify the gun battle in the housing project.

On December 15, 1988,

Davis was sentenced to five to fifteen years for weapons possession.

At his sentencing, Larry Davis spoke for twenty-five minutes:

“There is no justice for the African-Latino people,

I was supposed

to be on page twelve of the News—

Black Youth Killed By Police.

Instead, I wound up on page one

because I refused to die.”

The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association demonstrated outside the courthouse carrying signs reading

“We Bleed—Davis Walks”

and chanting

“Lar-ry, Lar-ry, wait’ll he shoots you;

the Fire Department will respond!”

The police demonstration ended with fifty police officers

shutting down traffic at the Grand Concourse and 158th Street.

The police had been on trial as much as Davis had.

Tensions between law enforcement and the community it served

were at an all-time high after two decades of high crime

in the five boroughs.

Earlier in 1988,

a twenty-two-year-old police officer was murdered

with five shots to the head

in his patrol car in South Jamaica, Queens.

The death of Eleanor Bumper in 1985,

an elderly and emotionally disturbed

black woman shot

in her home

twice

with a shotgun by a police officer,

served to escalate racial tension in New York City.

Counter-protesters shouted at the officers,

“What about Goetz? That son of a bitch got only six months!”

Bernie Goetz was a white man who had gone

on a Saturday afternoon shooting spree

on a downtown bound 2 train

between 14th Street and Chambers

injuring four young black men, paralyzing one for life.

Labeled the “Subway Vigilante,”

Goetz envisioned himself as an insurgent

on the front lines of New York City’s criminal rulers.

“Crack literally changed the entire face of the city.

I know of no other drug

that caused the social change that crack caused.

You can’t name another drug that came close….

For just $5 to $10, you could get it again and again.

New cash flows, new organizations grew from the street up.”

It would not be until 1991

that the DA’s office would finally get the man

who had so profoundly humiliated them.

Larry Davis was convicted in the murder

of Raymond Vizcaino, who was killed by a gunshot

through a closed door on August 5, 1986.

It was in this landscape,

of freedom fighters and drug epidemics,

of paternal and cynical politicians,

that Larry Davis became

“a hero to some and a pariah to others.

For some,

a symbol of murderous drug wars

and for others, a symbol of widespread mistrust of the police.”

Davis said of Lynne Stewart:

“Everyone thinks Kunstler beat the case.

Lynne Stewart beat the case.”

Figure 1: Matt Kenny, Untitled (Blind Sheikh Press Conference), 2020

Figure 2: Matt Kenny, Untitled (Basement of the World Trade Center), 2020

Figure 3: Matt Kenny, Untitled (Lynne Stewart), 2020

Figure 4: Matt Kenny, Untitled (Arrest of Larry Davis), 2020

Figure 5: Matt Kenny, Untitled (Rudy in costume), 2020

Matt Kenny was born in 1979 in Kansas City and raised in New Jersey. He studied painting at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. After graduating, Kenny moved to New York in the first week of September 2001, just prior to the terror attack on the World Trade Center. Since 2013, Kenny has exhibited work with Halsey McKay Gallery and The National Exemplar, along with projects at 55 Gansevoort and Cooper Cole Gallery in Toronto. This text an excerpt from his book, Coercive Beliefs, that was originally published in 2017 by the National Exemplar and is accompanied by a series of new drawings executed in 2020, during quarantine.