Island Life

By Andrew Durbin

EXPLORING JACOLBY SATTERWHITE’S ‘ISLAND OF TREASURE,’

THE MOST RECENT ENTRY IN HIS REIFYING DESIRE SERIES

Drive it in between.

—Grace Jones

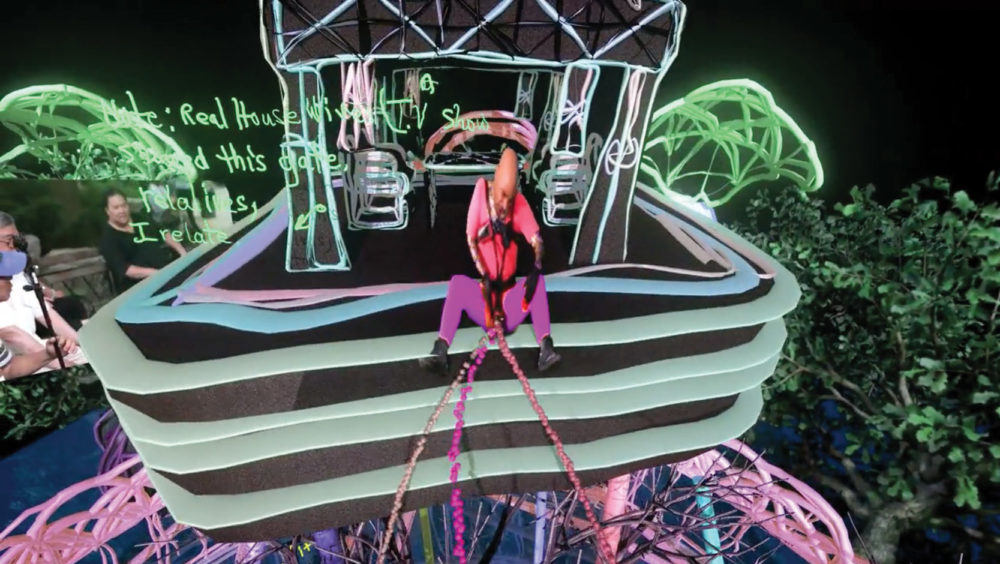

Fig. 1

Outside Jacolby Satterwhite’s studio, housed in a small office of One Liberty Plaza on a floor of studios managed by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, One World Trade Center takes up the bulk of his generous view of the city with its massive, torqued body. I say body because it’s one of those strange buildings that doesn’t just feel present, it feels alive, for whatever reason, vibrating to the undetectable rhythms of someone’s history, maybe even ours. At this moment, it is the tallest building in the United States, a fact it wears proudly in the tremendous spire that sways at its top. During my first studio visit with Jacolby in December 2013 the sun set and all the windows of the high rises around us lit up with the slow winter palette of early sunset: yellow, orange, red, purple, each draining into one another until it all turned to night, at which point Jacolby and I finally joked about the power drama of the sun going down on Lower Manhattan. I begin with this part of the city around the site of the World Trade Center, with its austere memorial for the gaping holes that scabbed the bottom of the island for the better part of the past decade, because that’s where Jacolby’s Reifying Desire 6: Island of Treasure, the last of his Reifying Desire series, begins. It begins where we begin again.

The word treasure comes, by way of the French, from the Greek word thésauros, from which we also get the word thesaurus. The Greek means “a concentration of valuables,” and so from those valuables we’ve drawn out a concentration of words. Like a thesaurus, Jacolby’s work is replete with allusive language. There is this sense in Reifying Desire 6 that every object, detail, and body is the thing it appears to be as much as an item in a set of potential locutions. The work’s visual grammar owes a great deal of its force to ideas in language, particularly recursion, a linguistic device that allows clauses to be embedded into sentences. In Jacolby’s work, one thing is always embedded into another is embedded into still another. This recursive strategy leads to multiple doublings throughout, from objects (both as real and animated or filmed) to performance (Jacolby often dances in front of his videos in a suit that, in yet another doubling, incorporates a screen that plays another film). Recursion has always seemed to me to be a method of beginning again, bearing—like childbirth—one thing out of the same thing. For Jacolby, this often means incorporating material from his family and his past.

As with his other films, much of the visual material in Reifying Desire 6 is sourced from his mother’s drawings of objects, many of which are blueprints for already-existing products (vacuums, soda cans, vibrators, etc) and architectural designs. Patricia Satterwhite’s work appears in Jacolby’s films as bright, shimmering animated objects and structures. Her hand-written notes orbit these things, describing what they are and how they function. (To return to treasure: the words and letters flash like jewels and coins.) The architecture of the spiraling city at the center of the film, along with its visual and linguistic décor, follows the logic of recursion, doubling back to its mathematical definition: the process through which a procedure invokes the procedure itself, causing things to multiply and embed, give birth and be born. In Reifying Desire 6, the text within the film and performance elaborates an architecture that in turn elaborates more text and more performance. The introduction of one image causes other images to proliferate. A favorite example: trash bags in Chinatown become the Resource Woman, a pump of energy at the center of an elaborate ritual to energy use. In this sense Reifying Desire 6 returns to another strategy of language—the poetic—in that it concerns itself with the making of things.

Fig. 2

The novelist Rachel Kushner writes that a poem is a gesture with no possible rebuttal. To modify her slightly, I’d say that a poem—the poetic—is a gesture with no possible rebuttal because it refutes itself. The poetic breaks down, as systems generally do, and therein resides what makes it so compelling: beauty, maybe, but one that emphasizes its (our) own fragility. I like fragility. I think Jacolby does, too. In his work, fragility is the tendency in complex systems—bodies and cities—to catch a cold, to get sick, and to collapse. Viruses and cancers accelerate a process already in effect, and he locates in that quickening biological economy a currency of images that always refer back to what sparked them: tumors, cancers, cell splitting. Bodies misaligned. In these processes, Jacolby discovers dreamy, circuitous metaphors for how we live, forcing them to rhyme with dance, sex, and city life. And this impulse to metaphorical logic allows him to collapse city and body into one, turning one into the other, co-dependent and living, multiple and singular. That biological reality is always historical, too. Figures made of T-cells are lynched in the uncanny field while Jacolby dances below them. The history of the place he comes from, the troubled history of his home state South Carolina, finds itself stitched into the psychobiological world of the film, metastasizing health into more than just a personal concern, but a communal one too, a state of being that effects the structure of experiential reality, blossoming and folding like beautiful cancers that corrupt and split the city-body into more city-bodies. There is no place, there is no time: like history (like recursion), processes of the body prefer to loop rather than progress.

Consumption and procreation unify these recursive city-bodies. In the film, sex between two people—Jacolby and the porn star Antonio Biaggi—is multiplied into a circling orgy below a tree upon which another Jacolby sits, birthing dancers into translucent tubes wrapped around the tree. The haphazard movement of the couple’s arms organizes into a ground-level ceremony in celebration of the complex birthing practices surrounding the tree.

At the center of this performance, his mother’s drawing of a triangle glows with Rihanna’s face glimmering within it, a mournful eye that, for me, suggests the supernatural isolation that fame—separation from the city—brings about. Jacolby’s mother’s writing floats free of this orbit of bodies, satellite commentary to consumerist over-drive to invent and be invented as unique, original, famous: “Note: Real House Wives (TV Show Showed this gate.) Relatives, I relate.” Relatives, relations: the two recur and bind the film’s many threads into pageants and rituals that explore open themes like sex, health, and energy. Ritualized at the center of this is motherhood itself, and the implicit injunction to make.

Reifying Desire 6: Island of Treasure refers to another island of treasure: Treasure Island Media, the notorious porn house that features men—some of whom are HIV positive—engaged in bareback sex. By removing the condom, a lot gets said (quite literally: a trademark of the films is their use of subtitles to narrate unseen intimacies like ejaculation), but one clear thing seems to be the reassertion of contamination, of fluid exchange as inevitable to sex. Treasure Island Media, like Island of Treasure, reminds us on the one hand that the separation of bodies is imperfect at best, on the other that this imperfection can be a source of desire and a reason to fuck. In one of the many explorations of the body-in-sex, Antonio Biaggi fucks multiple iterations of the artist, critiquing the operational hurdle non-procreative sex introduces into “natural” reproductive cycles.

Fig. 3

Jacolby situates us, his viewers, amid the (often) contradictory drives to assume the role of progenitor, complicating our efforts to make a human or a film. Deleuze writes in his essay on deserted islands that the longing for the island is a longing to separate and in separation be made new. Since this desertion is only ever imaginary the island has long been a site for the invention of selves—a place to begin again. In its totalizing separation, the island always points toward a radical form of integration and community, one established by clear borders. And like the porn house and Jacolby’s film, the island where we hide our treasure (a person, a history, a city, a film) is a place where we can situate myths about desire and the self, too, and within those coordinates allow for more mythologies to flourish. For Treasure Island Media, this myth is exploited in the inverse: the HIV-positive man is de-islanded, reintegrated into sex without precaution. Jacolby’s film makes a similar effort to return the isolated individual—a model he filmed dancing by him or herself, trash bags on the street, his own sex life—into a public community of others. Deleuze writes about literature and islands what might be said about film: “[It] is an attempt to interpret, in an ingenious way, the myths we no longer understand, at the moment we no longer understand them, since we no longer know how to dream them or reproduce them.”

In Reifying Desire 6 and its five previous volumes Jacolby and his actors (many of them recruited from his circle of friends or the streets outside his Recess studio) dance in the rendered cities of his digital atopia. The semi-random nature of their inclusion and their atypical dancing—they aren’t professional dancers, and how they dance is all their own—is structured by the various pageants Jacolby coordinates in his films, from the subway cars filled with dancing passengers drifting trackless through his city to his sex scene with Biaggi. What might seem to be simply uncoordinated movement is appropriated and synced into a larger arrangement of bodies recruited for the various rituals that mark the film. Jacolby’s actors are filmed separately, so they have no idea what troupe they’ll be part of. Their formalization into the structure of the film, what forces them into community, mimics how cities make populations of unrelated individuals cohere into a locality. Their bodies drift and circulate, but always maintain their social affinities through dance. They are also folded, recursively, into one another, and into a new city, one that none of us actually inhabit, that gives them form. This movable organization of bodies strikes me as an exemplary image of the contemporary city today, especially New York, with its manifold contradictions that allow people to live in fluid relation to one another—as neighbors in the real and online.

Fig. 4

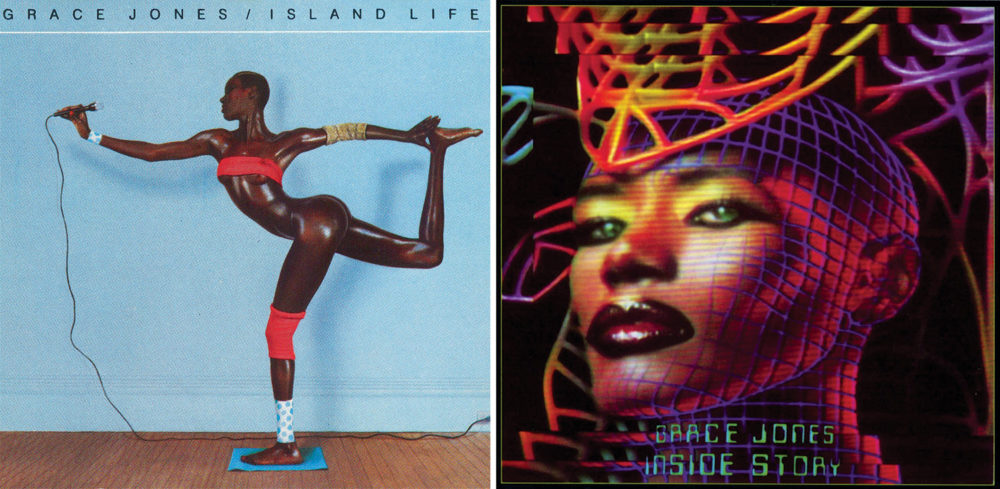

I’m reminded of one of my favorite albums: Island Life by Grace Jones. Jacolby was born shortly after the album was released and before her follow-up, Inside Story, but between the two feels like a good place to locate him and his practice. The iconic cover of Island Life features an oiled, leotard-wearing Jones posed mid-stretch before a blue wall. Her body is tense and sculpted. Its formal visual quality is countered in Jones’ follow-up, Inside Story, which features a portrait of the artist illustrated to appear in mid-digitization.

Her face is drawn into an electric grid that frames her glossy lips and her green, frozen eyes. The two albums suggest two categories of portraiture—the first analog, the second digital—that Jacolby’s own work frequently pivots between (filmed actors, rendered ones; performance in the real, performance on film). In both these album covers, there is an emphasis on the performance of categories (self, gender, history) beyond the body, a performativity that Jacolby frequently refers to: he often dances elaborately in front of his video works, and for hours at a time, striking poses that are as intensely held as Jones held her own body on the cover of Island Life. Jones’ visual elasticity, like Jacolby’s, allows her to assume multiple physical roles, from the bizarre to the sublime, the beautiful to the ugly. Jones effaces these categories by pivoting between them with breathtaking velocity. The broad range of her visual and musical work, which often distorts our expectations of what it means to be a beautiful pop star by also asking what it means to be black, to be multi-talented, to be multi-genre, questions exemplified in the covers of Island Life and Inside Story, propose a theory of the self that argues that we are compelled by these divisions and their blurring, and that the architecture defined by such splits and leaks and bleeding edges offers an ontological map of many routes and segues. Again: the fluid relations between neighbors, here and a poem is a gesture with no possible rebuttal elsewhere. I think Jacolby’s a little in awe of this map and the potential paths it offers, and so he chooses—like Jones did and does—to take them all. What it means to reify, one: to make concrete. Jones and Jacolby concretize the differences that shape their bodies, and their sense of the world and its turbulent histories, by privileging the ornate disarray that marks that vision. What it means to reify, two: to create island space, wherein the possibilities of the self and its performance can take root.

Fig. 5

Like Jones, Jacolby doesn’t dwell on any singular island: he has ritualized this island-making potential into a practice that calls forth objects, bodies, and places into numerous, evanescent, interconnected realities. I don’t have any rituals except one: a McDonald’s Shamrock Shake in Times Square on or around St. Patrick’s Day. How this started is a little vague for me, but I think it began in 2010 and I’ve kept it up ever since—even though I’m lactose intolerant and can usually only manage a sip or two under the dizzying LEDs of the so-called center of the universe before I have to toss the Shake. The Shamrock Shake is a miracle of advertising—a recursive emblem of our present’s unshakeable desire to save and sell: despite its sickly color, its mucous-like consistency, and its inability to melt (leave a Shake like that in the sun and it just warms up and turns to something like concrete), it’s hugely popular. Hugely. Like the McRib everyone’s probably in on the joke and that releases us to a frenzied love for a thing that very much has nothing to do with what it says it is. There are no ribs in the McRib, though the meat has been stamped to look that way. Similarly, there is no milk in the Shamrock Shake, just high fructose corn syrup, water, sugar, natural flavor from a plant source, Xanthan gum, citric acid, sodium benzoate, yellow 5, and blue 1. What I mean to say is that ritual is often rooted in the practice of exciting one thing into another, even if that one thing doesn’t actually exist. (More idea than thing.) Somewhere along that line Jacolby works, putting objects and bodies real or not in and of definition, generating covers and alibis, writing and rewriting figures into multiple lives until its original is obscured behind layers and layers of definition.

Broadway cuts down through Times Square where I like to stand with my milkshake and curves downtown, slightly east, toward Jacolby’s temporary studio at LMCC. I want to say “write” because it feels, with its many chapters, like a novel, but since it’s a film we say made, and that seems apt anyway. Making bodies, making place. It is what cities do, too: they make themselves, over and over again, elaborating structures in which more structures—lives, bodies, histories—house themselves. The thesis of any version of Treasure Island, and of Island of Treasure, is the same as that of cities, that we must conspire together to seek the hidden place that we cannot say with any confidence will actually be there when we arrive where it is said to be. And yet we go on looking for it.

Figure 1. Still from Satterwhite’s video, Reifying Desire 6: Island of Treasure (2013), shown at the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy the Artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles.

Figure 2. Still from Satterwhite’s video, Reifying Desire 6: Island of Treasure (2013), shown at the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy the Artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles.

Figure 3. Jacolby Satterwhite performance. Photo courtesy of Max Linder.

Figure 4. Left: Grace Jones’ Island Life,1985, Courtesy of Island Records. Right: Grace Jones’ Inside Story,1986, Courtesy of Manhattan Records.

Figure 5. Still from Satterwhite’s video, Reifying Desire 6: Island of Treasure (2013), shown at the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy the Artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles.

Andrew Durbin is the author of MacArthur Park (2017) and Skyland (2020), all from Nightboat Books. In 2018, MacArthur Park was a finalist for the Believer Book Award. He is the editor of Kevin Killian’s Fascination: Memoirs (Semiotexte, 2018) and the chapbook series Say bye to reason and hi to everything (Capricious, 2015). His fiction, criticism, and poetry have appeared in BOMB, Boston Review, frieze, Mousse, The Paris Review, Triple Canopy, and elsewhere. He is the Editor in Chief of frieze magazine.

©Andrew Durbin, this essay first appeared in Cluster Mag, 2014