- Source: SWITCH

- Author: JON DAVIES

- Date: SPRING 2010

- Format: PRINT

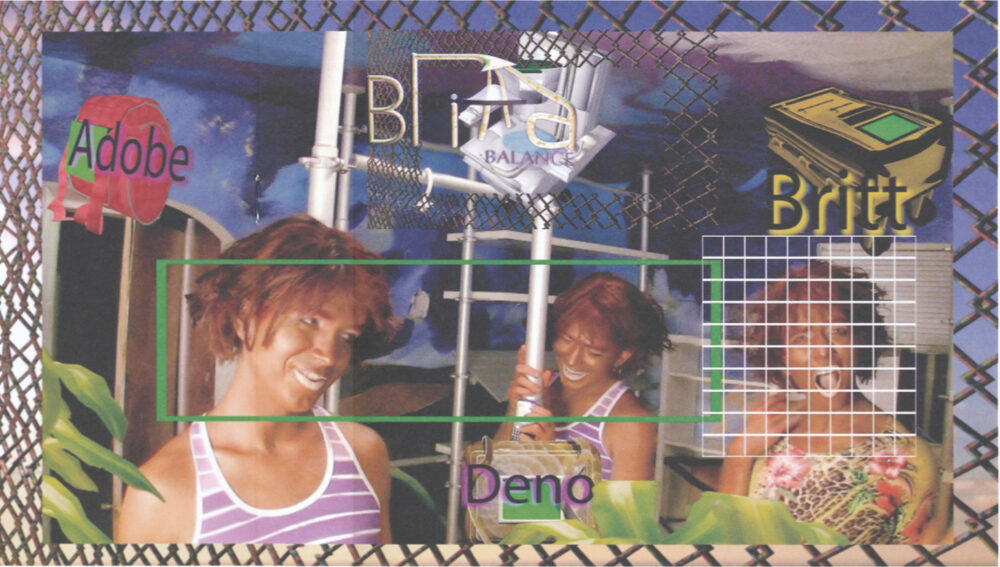

Ryan Trecartin: Data Purge

Ryan Trecartin

P.opular S.ky (section ish), 2009,

Still from an HD video. Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York).

The young American artist Ryan Trecartin’s vertiginous performance, media and installation practice seeks to give people physical form to the abstractions that govern life in the digital age. The structures and motifs of globalized, networked media and communications become characters, narratives and environments in his work.

Cyberculture îs rewired through the fallible human body, with all its entropic, expressive energies and potential for physical and communicative breakdown. The result is a messy and excessive sensory bombardment that scrambles his viewers’ processors and rewires their comprehension of cinematic storytelling, time and space. Consequently, Trecartin’s work has commanded the art world’s attention in a matter of a few short years.

Trecartin was born in 1981 in Webster, Texas, and raised in rural Ohio. He attended the Rhode Island School of Design, where he studied video and animation, receiving his BFA in 2004. Relatively cheap to live in, packed with art students and close (but not too close) to New York, the city of Providence is known for being a hotbed of discipline-crossing DIY experimentation in terms of culture and community. It was here that Trecartin found his crew of like-minded creators, dubbed the XPPL (Experimental People Band). Upon graduation, Trecartin and friends decamped for New Orleans and then, following Hurricane Katrina, he has lived itinerantly, working in Philadelphia, Miami and Los Angeles, among other locations.

Ryan Trecartin

K-Corea INC. K (Section A), 2009,

Still from an HD video. Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York).

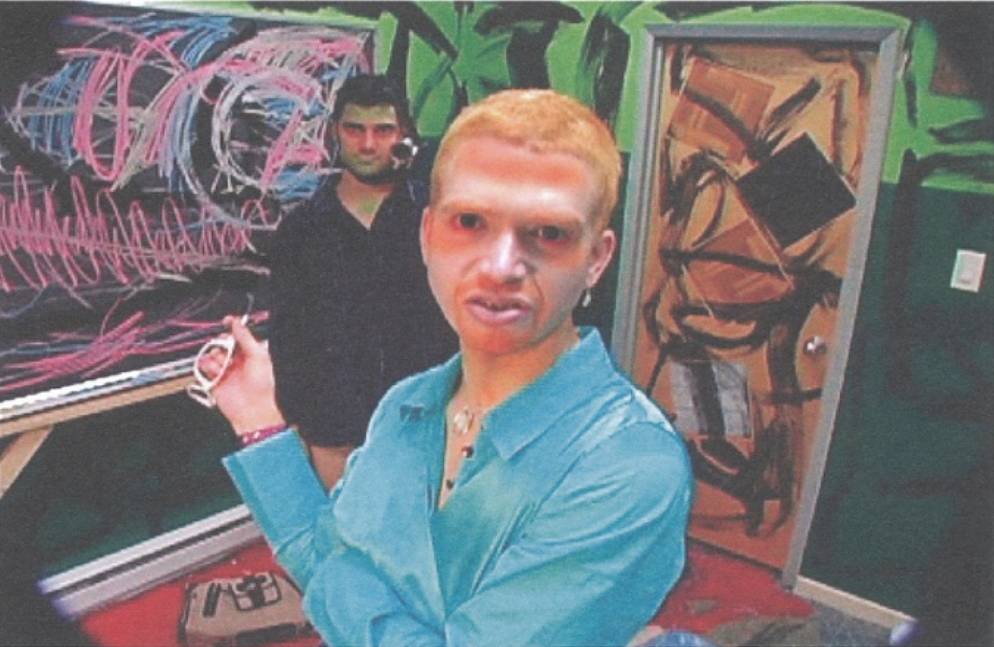

Ryan Trecartin

I-Be Area, 2007,

Still from an HD video. Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York).

Trecartin captures the addled mental state of a generation raised by the Internet and the glut of information (though not necessarily knowledge) that it offers access to. Through his queer hysterics/theatrics and the hallucinatory digital manipulation of every image, object, space, and sound on-screen, Trecartin’s work is a seething stew of the bodily, the discursive and the virtual. He transforms the space of the screen into that of a computer desktop with hundreds of windows open, each addressing you with a character high on what writer Wayne Koestenbaum has succinctly called “connectivity” and “morphability.”

With seemingly no history to speak of, Trecartin’s attention-seeking characters spout a painfully ‘contemporary’ dialogue composed of pop-culture references, trendy buzz-words, harebrained theories, talk-show confessions, and text-message shorthand. This sub-cultural meta-language might sound nonsensical at first, but on closer inspection it reveals itself as a witty and incisive (if absurdly circuitous) diatribe. Working in an improvisational performance tradition with mostly nonprofessional actors, friends and acquaintances of all ages, genders and races, Trecartin writes a script but lets his performers play within it.

The characters’ rapid-fire sentences (or fragments thereof) are more often than not punctuated with an act of physical destruction: Bodies plunge through walls, smash picture frames (or bed frames) or swing sledgehammers through windows. This violent body language amplifies each spoken word through seemingly nihilistic gestures, but only IKEA furniture ever breaks, not human beings. Trecartin’s mash-up of a script is frequently delivered in an exaggerated, neo-Valley girl tone distilled from the likes of Paris Hilton and Britney Spears. Similarly, the cadences and beats of their frenetic speech – and the pauses for breath and accentuation in between – are dislodged from rhetoric logic. This inhuman, synthetic-sounding organization of verbal language is further intensified by Trecartin’s digital manipulation of many of the voices and statements in post-production. The most punchy Trecartin sequences – the ones that really stick – use montage to create rhythm and something approaching sense from his mind-melting flow of audio-visual content.

Trecartin’s characters are digital data and they know it. Subject to being designed, rendered, and transmitted like files, they can fluidly shift identity, form and affect at the press of a button – not to mention falling out of ‘acting’ and into ‘being’ at the drop of a hat.

Trecartin has maintained a fascination with cloning and the multiplication of identity throughout his multifarious projects, from the cracked coming-out story A Family Finds Entertainment (2004) to his suite of seven videos – the interconnected trilogy K-Corea INC. K (Section A), Siblings Topics (Section A) and P.opular S.ky (section ish) (all 2009), and the four-part series R’Search Wait’S (2010) – all showing together for the first time in The Power Plant exhibition ‘Any Ever’. This theme spans the increasingly overlapping realms of biology and the digital, just as the successful cloning of ever more complex and sentient mammals parallels the culture of self-replication fostered by social media. YouTube, for example, provides a hotbed for the generation of an infinite number of performances of the self, with even the most bare-bones confessional video blog inevitably constructed in dialogue with the dizzying archive of moving-image material to be found on the site. (And of course, each of these posted videos becomes the material for an infinite number of remixes and remakes, homages, and perversions authored by millions of savvy autodidact editors.) Facebook, for its part has honed the careful cultivation of one’s public image into a digital art form, though again always in dialogue and in tension with other users and their whims (you can un-tag yourself from an embarrassing drunken photo, for example, but you can’t delete it). The figure of the avatar in gaming, meanwhile, is so familiar in popular culture as to have lent its name to the colossal entertainment product that is James Cameron’s 3D, CGI film Avatar (2009).

Ryan Trecartin

Installation view: 'The Generational: Younger Than Jesus', New Museum (New York), 2009.

Still from an HD video. Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York).

Such a bloated corporate enterprise as Cameron’s seems to be from an entirely different planet than the grainy pixelation of the online video realm where Trecartin’s work has found a popular audience outside of the art world. Instead, Trecartin’s spectacle is a kind of DIY sci-fi: the future will be experienced through multiple web browsers and home editing-suite filters. I-Be Area (2007) remains perhaps the purest and most deserving of the term ‘epic’ among Trecartin’s cinematic concoctions, with its dual protagonists of I-Be 1 and her clone I-Be 2 and its preoccupations with adoption and other non-biological forms of connection and reproduction. Trecartin’s characters are digital data and they know it. Subject to being designed, rendered, and transmitted like files, they can fluidly shift identity, form and affect at the press of a button – not to mention falling out of ‘acting’ and into ‘being’ at the drop of a hat. This ostensibly liberating power of pure mutability carries a dark undercurrent, with everyone screaming over each other to be heard, and no stable home of selfhood. These concerns with family and biology are resurrected in Sibling Topics (Section A), which begins with a character named Carryon Ova – who boasts a digitally-distended, constantly mutating pregnant belly – addressing her quadruplet daughters Ceader, Britt, Adobe, and Demo (all played by Trecartin, all of their subjectivities blurred).

K-Corea INC. K (Section A) finds Trecartin portraying just one of dozens of near-identical ‘K-Coreas’ from all over the world attending an endless company meeting. Each is identifiable primarily by their mock-ethnic accent since they share the same blonde wig, glasses and business-casual women’s wear (all part and parcel of their collectively performed whiteness and womanhood, which Trecartin calls “work-face”). Their Sarah Palinesque style and hyperbolic pronouncements, mass-produced to become a kind of uniform for the jet-setting businesswoman of today, takes on added menace with the quip: “rethinking the word humanity as an object with a goal.” Here Trecartin finds a delirious corporeal form for the unfettered global traffic of capitalism: each is an “offshore identity storage unit” – certainly nothing more human than that – enacting a hyped-up version of the corporate bump and grind and always at risk of being made redundant by their formidable lady-boss, Global Korea. A climactic sequence features an airplane full of the Koreas screeching and getting drunk, eventually setting a stewardess – who resembles more of a Leigh Bowery creation than Karen Black in Airplane – on fire. (The airplane is an anachronism: none of these characters actually require hulking masses of steel to travel through space and time, just willpower.) The fuselage set we see is a homemade construct installed in someone’s house, with the ‘real’ outside world visible through the back windows – nothing is seamless.

It is important to point out here that Trecartin always works collaboratively – most commitedly and from the very beginning with Lizzie Fitch – and returns with the same troupe of performers from one project to the next, though each is inevitably expanded with people met or found along the way. His projects register this ad hoc community’s impulses towards both creation and destruction, as characters, sculptures, paintings, and architectures are built up only to be destroyed in the cathartic, even orgiastic ritual that is the shooting process. (Arguably this libidinal dimension casts the equally energy-consuming but solitary work of editing – an intensive, monomaniacal process that Trecartin claims is fueled by junky microwave meals – as a masturbatory one.)

While much ink has been devoted to Trecartin and his work, very few critics have described his non-linear experimental narratives in detail, unless quoting directly from the artist. The speed and simultaneity of the plot threads, sudden transformations of the characters, fluidity of time and space, and shrill mode of delivery make the narrative structures confusingly rhizomatic and abstruse, tough to take a step back from and summarize beyond the subjective pleasure and terror-filled experience to them. This intense degree of abstraction mirrors the impossible-to-grasp paroxysms in the global economy – particularly the recent ‘crunch’ that seemed like it might doom us all to eating foraged twigs and berries – and the increased immateriality of credit and of finance. Increasingly difficult to comprehend too are the changes to our genetics as technologies become more and more intricate and the once-unimaginable becomes real. Digital video – amplified through animation/CGI technologies – is in a unique position to similarly make the imaginary tangible and manifest: what physical bodies won’t do, pixel-tweaking can.

Ryan Trecartin

P.opular S.ky (section ish), 2009.

Still from an HD video. Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York).

However, it is remarkable just what these bodies can do, particularly Trecartin’s athletic shape-shifting, which has seen him transform into dozens of distinct characters through costumes and make-up, not to mention tanning: Shin, Amerisha, Pasta – their names part Warhol superstar, part Walmart. While the models of identity proposed in Trecartin’s videos feel radically new, they fall into the legacy of queer underground film and performance figures like Jack Smith and John Waters (frequently name-checked in writing on Trecartin) who advocated perverse dress-up, striking an exaggerated pose and rabid acting-out as flaming forms of self-fashioning and self-projection. In ‘Any Ever’, the possibility for imaginative identity construction is also opened up for viewers: As people walk through the labyrinth of distinct ‘containers’ that Trecartin will create at The Power Plant, they will be confronted with non-sequential, open-ended and polyphonic cinematic realities that, in Trecartin’s mind, are to be ‘edited’ by viewers into some sort of semblance of cohesion depending on where or how they direct their attention. Each of these framing environments will take on another form – board room, airplane, etc. – echoing how the settings and spaces in the videos themselves are of decidedly unstable materiality, constantly shifting in terms of what worlds they enclose – and what possibilities they present.