- Source: Observer

- Author: Craig Hubert

- Date: January 22, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Robert Mapplethorpe’s Photos No Longer Seem Shocking in 2019

—And That’s a Good Thing

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self Portrait, 1980. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

When Robert Mapplethorpe died on March 9, 1989, of complications from AIDS, he had yet to reach the apex of his fame. That would come a few months after he was gone. In June of that same year, following a movement led by conservative senators Jesse Helms and Alphonse D’Amato to dismantle the National Endowment of the Arts, the sheepish cancellation of a touring exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s work called The Perfect Moment brought his images to their feverish attention. The work was so offensive, Helms told the New York Times that same year, that he had trouble even describing it to his wife.

This campaign, publicized by Helms and backed by the Christian American Family Association, would stretch on for years, and place Mapplethorpe and others and the center of what is commonly referred to now as the culture wars. It made the photographer a household name, even if many had never seen his work, especially those images that were deemed most controversial. At the same time, it simplified Mapplethorpe’s artistic output, singling him out as a cause to get behind. A familiar argument was that the beauty of the images, their classicism, outweighed charges of pornograpghy and offensiveness. Luc Sante, with only a few years hindsight in 1995, wrote that “many of his photographs will probably appear most notable as artifacts of the complicated and fascinating time in which they were made—certainly a nobler fate than to wind up as mere decor, which is another possibility for them.”

Their actual fate is somewhere in between. Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now, a two-part, nearly year-long exhibition that opens at the Guggenheim on January 25, rides an almost decade-long wave of renewed appreciation and widespread cultural re-embrace of the artist that began with the publication of Patti Smith’s 2010 memoir Just Kids: there have been fashion collaborations between designers and his estate, a reverent HBO documentary, and an upcoming fictional film starring an actor who used to play Dr. Who (Matt Smith). And during that same period, cultural standards have loosened, to a degree. Much of the content that people—both supporters and detractors—deemed hard to look at in Mapplethorpe’s body of work can now be viewed easily by any teenager with an open mind and a smartphone.

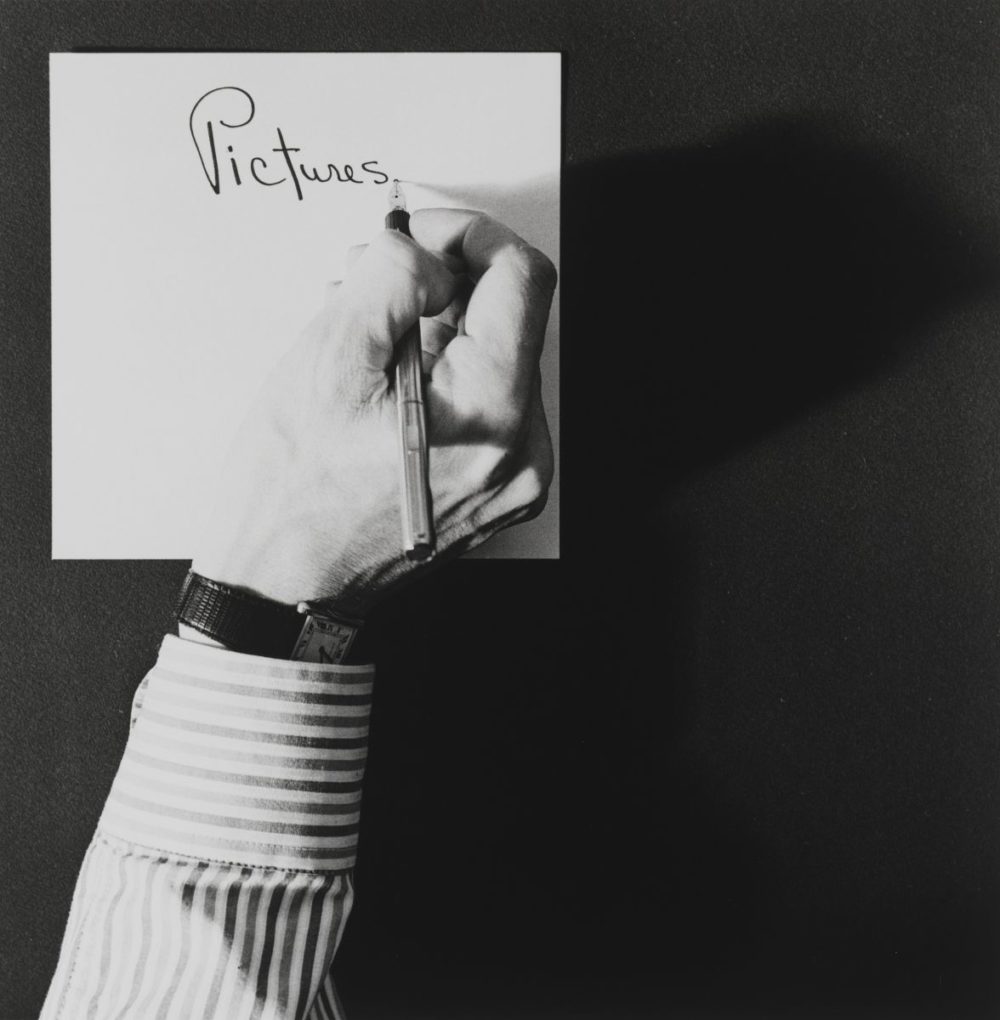

Robert Mapplethorpe, Pictures / Self Portrait, 1977. Gelatin silver print. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe, Pictures / Self Portrait, 1977. Gelatin silver print. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The stain of scandal still remains, though, and a Mapplethorpe show is bound to attract a large number of visitors. There have been over 100 gallery and museum exhibitions of his work since 2009, including a comprehensive exhibition split across the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2016. There will be more, certainly, to come. In an era of bold-name prestige shows, a Mapplethorpe exhibition means big business.

But does his work still carry the same electric charge? Viewing Mapplethorpe’s photographs through the lens of controversy would seem to consign them to relics of a bygone era. Like many contentious works of the past, it’s hard to see what all the fuss was about. People looking at his work for the first time, encountering it without having lived through the period in which it was subject to homophobic screeds on the Senate floor and at the center of lawsuits, only aware of it through its subsequent commodification, will have to find other paths toward appreciation.

The most immediate thing that jumps out looking at Mapplethorpe’s pictures today is their humor. Man in Polyester Suit, 1980, for instance, is one of the best visual jokes in his body of work: a man wearing a cheap-looking suit, cut off at the head and knees, his penis casually unfurled in the middle of the frame. He looks like a stockbroker who forgot to zip up his pants after too many bumps in the bathroom at The Odeon. In Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter, 1979, two leather-clad men, one sitting and shackled to another standing, pose as if for a prom photo.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1982. Gelatin silver print. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Mapplethorpe could also poke fun at himself. In Self-Portrait, 1983, he stands in front of a pentagram wearing a leather jacket out of a noir film, posed with a machine gun like Patti Heart in her SLA portrait. He’s flaunting his rebelliousness.

Looking at the entirety of Mapplethorpe’s output, it’s also clear that what was thought controversial was only a small percentage of the work he made, and much of that was relegated to the notorious “X Portfolio,” a series of 13 images born out of his active participation in the S&M subculture. Many of the nudes he produced—of frequent subjects like the bodybuilder Lisa Lyon or the late dancer Derrick Cross—are chaste by today’s standards. What is striking still is their formal beauty, impersonal and reverent. They are monuments to the human body, frozen as if marble statues. His objectification was all consuming, but his ideal subjects conformed to myths of perfection. While many of these portraits result in images that are alluring, they also reveal something about Mapplethorpe’s own standards of beauty, and racial stereotypes that look less radical with the benefit of time.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Calla Lily, 1986. Gelatin silver print. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Mapplethorpe would go on to photograph both flowers and, not surprisingly, statues in the same way. The move toward these immobile objects are also the most in danger of becoming decor; their stillness, devoid of the sexual politics of a human subject, render them non-confrontational. In the hands of a lesser artist, they are the type of images you would see hung on the walls at a dentist’s office. But in the context of Mapplethorpe’s life and career, they are radical in their seeming blankness, and in many ways his greatest achievement: formally beautiful and erotic, they are also warm and inviting, open to suggestion and contemplation. Their controversy is less obvious but still present.