- Source: The New York Times

- Author: Randy Kennedy

- Date: November 12, 2015

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Recalling the Outlaw Eye of Dash Snow

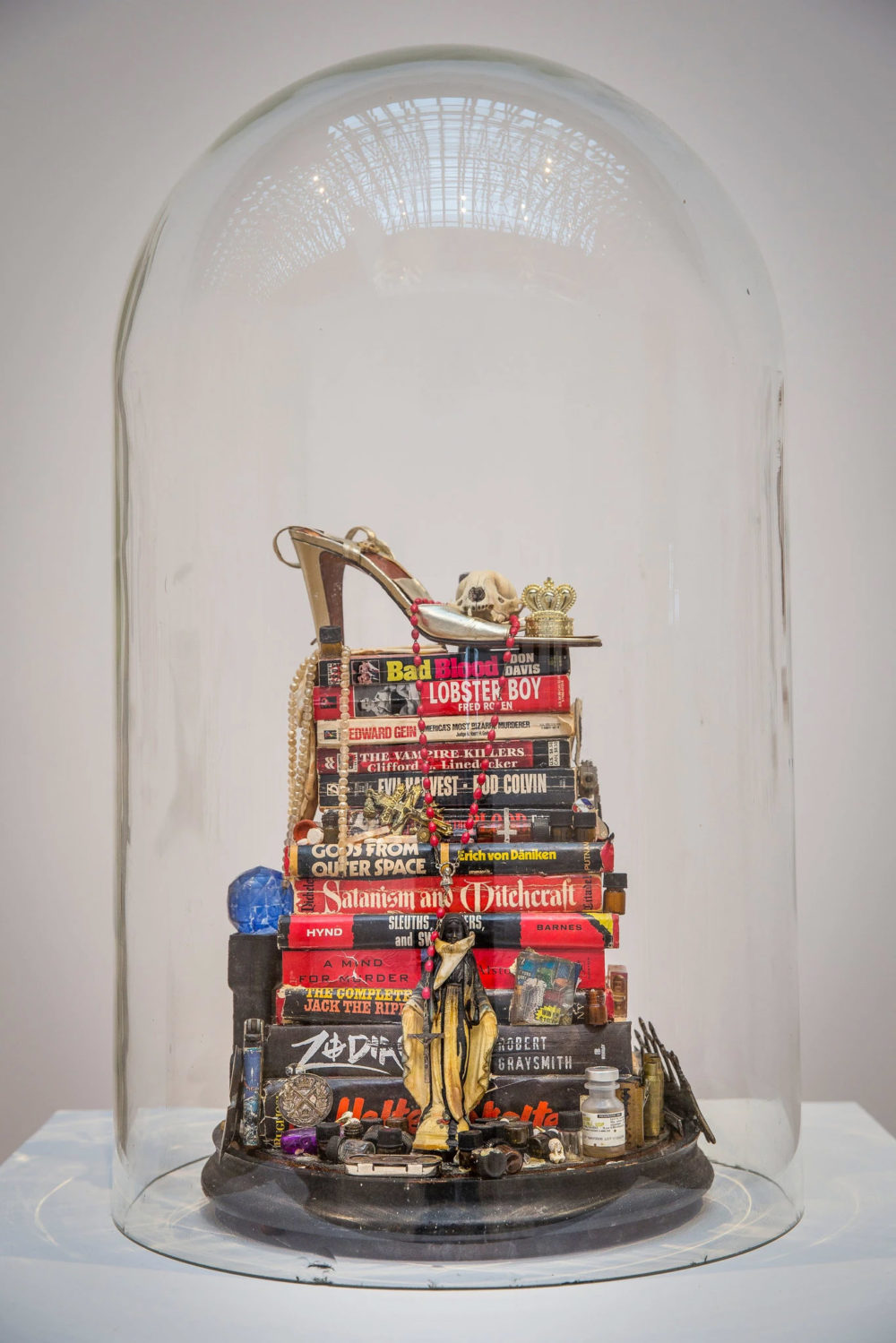

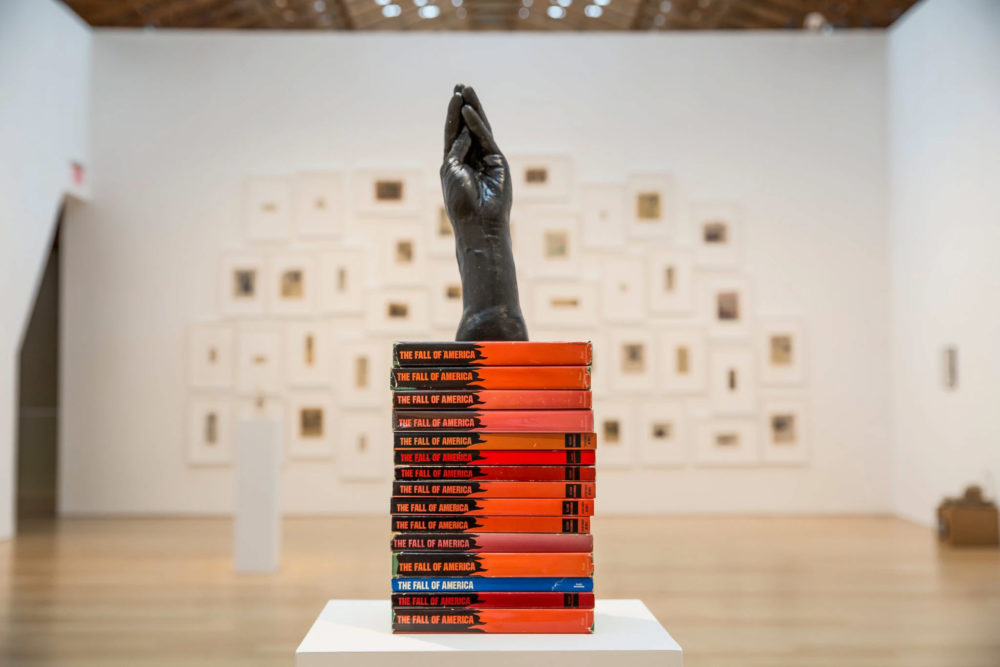

Dash Snow’s “Untitled” (2006-7), at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center,

in Greenwich, Conn. Photo credit Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

GREENWICH, Conn. — For a press-wary paranoiac, the artist Dash Snow towed around an immense burden of public myth during his short lifetime. By the time he died from an overdose in 2009 at the age of 27, he had come to stand almost single-handedly for a downtown New York art and party scene that arose just before 9/11 and flourished in the anxious years afterward, known for its drug-fueled excess and adolescent rebellion in the face of a city rapidly becoming more homogeneous, wealth-obsessed and heavily policed. That Mr. Snow came from art-world privilege — he was an estranged member of the de Menil collecting family — made the narrative that grew up around him all the more loaded. He was resented, glorified, dismissed and envied, often in the space of a single conversation, regarded as a genuinely troubled, politically aware poet of early 21st-century anomie or a heavily tattooed epigone of a counterculture that lost its steam long before his arrival.

The question of whether his artwork (photographs, collages, film, assemblage sculptures) had staying power was mostly lost in the noise. But his heyday — back when Rudolph W. Giuliani was in the mayor’s office; the Internet was young; Bushwick, Brooklyn, wasn’t a place that made you think of artists; and artists could still afford to live there (or almost anywhere in the city) — seems far more distant than the calendar suggests. The passage of time is now occasioning the first good look at what Mr. Snow left behind. The Brant Foundation Art Study Center, the publisher and collector Peter M. Brant’s by-appointment museum in Greenwich, Conn., has just opened “Dash Snow: Freeze Means Run,” a selection from the surprisingly voluminous output that Mr. Snow managed to generate in his few years.

On Tuesday, in a room at the foundation lorded over by a sculpture built from piles of true-crime books that Mr. Snow collected, I led a round-table discussion about the exhibition with three artists — Dan Colen, Hanna Liden and Nate Lowman — who were close to Mr. Snow and whose own art careers have become established over the last decade. The three helped organize the show (which runs through March 2016) with Blair Hansen, director of the Dash Snow Archive, who took part along with Mr. Brant. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

From left, the artists Hanna Liden and Nate Lowman; Blair Hansen, director of the Dash Snow Archive; and the artist Dan Colen

at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center in Greenwich, Conn. Photo credit Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

Q. Maybe we could start with all of you talking about when you first met Dash Snow and his life as an artist then.

Colen I met him around 1999, a little before Hanna did. I met him through my childhood friend, the photographer Ryan McGinley, who had a big influence on Dash, and he had started shooting Polaroids. But his relationship to the work was ambiguous. It essentially established what became the way he worked later, which was that the art was very fluid with his life. For him to define it as art eventually happened, but it was never very important to him. The first real apartment where he was making stuff was on Avenue C, with Agathe [the artist Agathe Snow, who married him in 1999, when he was just 18], and if you could imagine this show essentially deconstructed, that was their apartment: objects, newspaper clippings, images from all over the place, everything tacked to the wall, on the floor. Things would form, and he started making very articulate objects. But he did it almost the way somebody might read a book or watch a TV show. It was just like his home activity.

Liden I met him on the street outside an opening at the Alleged Gallery, I think, one of those openings that kind of just kept going out on the street. [Alleged operated on the Lower East Side, then Chelsea, from 1992 to 2002.] With the camera he was very disciplined. It was really a priority with him to make sure he had everything he needed. He wasn’t very happy if he didn’t have the camera, or if he didn’t have film. It was always really impressive to me. He started pretty quickly creating these kinds of performances around him, where it would feel organic, but then you’d realize afterward that he had this ability to direct the situation without it ever feeling like a photo shoot. I look at the pictures now, and I think he was really a very interested, and interesting, documentarian of that specific, crazy, confused time in New York City after 9/11, which was dark and scary, but there was also a freedom in it that we’ve lost a little bit.

Left, “Untitled (Mud Man)” (2008), a self-portrait by Dash Snow, at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center

in Greenwich, Conn. Photo credit Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

Lowman I met him just after 9/11, and I was living in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, and some graffiti writers that were friends of Dash’s were staying with me, sleeping on my couch. And one of them got stabbed, and so I went to the emergency room, and that’s the first time I met Dash properly — at Beth Israel. But I knew about him, because you’d just hear people talk about him, because he was one of those kinds of magnetic people. We barely had cellphones then. I didn’t do email. But there were only a handful of bars on the Lower East Side, and these neighborhoods that all the same people went to, and so you’d just know people, even if you didn’t really know them. It really was like a different city then.

Q. To what degree do you feel like the scene you were a part of was a reaction to the city’s becoming a more conventional, buttoned-down place in those years?

Colen We did have this very strong sense about Giuliani and that he was changing the city that we knew growing up and that we were trying to hold on to something that it once was.

Dash Snow’s “The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of” (2005), at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center

in Greenwich, Conn. Photo credit Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

Liden But I think there was no real way for such young people to predict really how quick and extreme that change was going to be.

Q. Snow had a reputation as an audacious street artist, which suited his outlaw personality. But it always seemed that the anti-authoritarianism ran much deeper, an aversion to power and control that veered into conspiracy-theory territory. How true was that?

Colen He didn’t have email. He didn’t even like to use the phone that much. He had a pager that he carried around forever. Once the Internet became unavoidable, he did everything he could to keep it out of his life, very aggressively.

Photo credit Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

Hansen I think that part of him was 100 percent genuine. He refused to have any kind of doctrine spoon-fed to him, to base his decisions on any social structure or to take anything on the word of someone he didn’t know.

Colen He was able to live on the edge like that, both emotionally and philosophically but also physically. His fears were much different than those of anybody I’ve ever met. Part of that grew out of graffiti culture, which is an outlaw culture. You’re inventing your own language. Everything is a secret. Everything is only for four people to know, and you’re always paranoid. But at the same time, he would open doors that no one else would open. And I mean that literally. You’d know by the look of a certain door not to try it, and behind it would be something completely crazy, and he’d take a picture of it. He would walk into any scene, say anything to anybody. Even the way he walked on a rooftop was amazing — he just didn’t register seven floors down [if he were to fall]. And there was beauty on the streets that he recognized because of that, beauty no one else saw.

Liden People also need to remember that the crew he ran with [a loose graffiti posse known as Irak] was probably the most diverse you’d ever see, as far as race and sexual orientation and everything. He was one of the most accepting people I’d ever met, and I think that fed into the way he made art.

Q. What was it like watching him make art? Or making it with him?

Lowman His kind of spontaneity always felt dangerous to me. It would get me very self-conscious, and I’d say: ‘You know, I’m not going to just do art right now, right here. My practice is different. I’m like, you know, a studio artist. I stare at the floor all day alone, and I make something, hopefully.’ Because that’s the way I learned, after lots of years in art school. But he always got to me, and we did end up making stuff together. To him it was just like a form of communication, and it always struck me as super-courageous, to put himself out there like that.

Colen I was always very good at defining things, and he was very good at reminding me that I shouldn’t always be doing that. He loved life, and he loved pushing it and making it insane, and then recording it, which was something he was amazed to be able to do.

A version of this article appears in print on Nov. 13, 2015, Section C, Page 23 of the New York edition with the headline: An Outlaw’s Eye After 9/11.