- Source: MUSEE

- Author: OSCAR LOPEZ

- Date: JULY 13, 2013

- Format: DIGITAL

Luis Gispert: The Joker

©Luis Gispert. Coach Mark VIII, 2011. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

What’s the difference between an art institute education and going to Yale?

It’s very different. My undergraduate experience was very theory-based, to the point that I stopped making things. Basically I read myself into a corner.

How did you translate that kind of experience at the Art Institute to your Yale experience?

There was a 2 year gap after undergrad, which was great because I got to travel and work, make art, but also live, and I started making objects again. I was making small films but I started making sculptures again, and thats what led me into graduate school. By the time I got to Yale, I decided that it was time to clear up everything from this dogmatic theory that was indoctrinated in me at undergrad. It became about being loose and to actually make things. I was working with Andrea Zittel, Jessica Stockholder, John Miller, and Joe Scalin. It was a very good diverse group of people. At that point, making art or what it was to be an artist was covered by a myth in my eyes. To see all these other working artists work, and to work with them after school as an assistant, the whole process of making art and working as an artist became demystified.

Transforming cars and urbanizing Haute Couture logos can be seen as a process of forgery. Do you see it as something inherently creative?

Definitely. My initial attraction to these people and the cars and the stuff they were doing was obsession. It was clearly a creative act, and even though they are not “artists,” it was their creative outlet. These cars were things they labored on for years in their spare time, and their level of craft varied from very fine to very amateur, and some of them could’ve hired people to have them work on them. I want to go back to the schoolteacher who owns a replica of the car from the Night Rider TV show; he took 5 years and something like $60K to do this project. The actual value of the car is like 3 grand, because it’s an old Pontiac, so it was a huge level of commitment and obsession for a thing and aesthetic. I immediately saw the parallel to an artist in a studio, the rigor, the sheer lunacy of being an artist because, as an artist, you don’t go into a project thinking, “Well, this is going to turn a profit or, this is going to mean something or, someone will care about it.” You’re just making this fucking thing, and if you’re lucky, someone is going to connect to it and even want to take it home with them. I mean, I’ve nearly gone bankrupt twice working on projects, and if you’re lucky you break even. And these guys – a mailman, on a mailman’s salary – is tricking out this old Mercedes into a Gucci fantasy car. And it was him and his buddy and his cousin over the weekends in his garage religiously working and tweaking it. Also with the garments, these ladies that have these little clandestine shops in their basements making dresses, making Quinceañera or prom dresses: the beauty of it is they’re not looking at the high end fashion magazines to get their cues. They’re going on the concept of what they like and what they want to do, and it’s an interpretation of something.

How does your work relate to or deconstruct ideas of beauty and taste?

That’s a complicated one. Those are almost like bad words: beauty and taste. Good taste, bad taste, like where you come from there is a certain aesthetic, a clear idea of beauty, and it’s inextricably tied to class and socioeconomic condition. Or education will dictate what kind of aesthetic you gravitate towards, and where I came from the baroque was very apparent in a very Latin, Cuban kind of way. So more was more. I discovered minimalism in Art school, and tried to understand it there. So its always been this negotiation, especially since my lifestyle is minimalist. I grew up in this house that was very cluttered so if you ran you’d knock something down. It was very curated, but very dense, so the kids were always terrified to play in the house because if you knocked something over you’d be done. So, I tended to strip things down. My early work tended to be an overloading of color and texture, but concepts of beauty attempt to deconstruct it and examine it. I mean, I’m not an academic or a theorist, so a lot of the work tends to be rather intuitive, and instinctual, and I have a road map of things that stick out to me. Like this forgery, the real basic one. The people who buy these brands when they’re real, versus the people who buy the fakes or make the fakes: What’s the difference in their lifestyle, and the discord? It’s the concept of customization, or the ghettoizing of something. I mean ghettoizing not in a pejorative way; I mean it in more in a colloquial way of making it legitimate on the street. So you take a luxury car, a luxury brand, and you do what they say is ‘chop and screw’, you change it, remix it, you customize it, and now it’s in another part of the world and it’s still a luxury item, but it looks nothing like when it did coming off the assembly line. So you got the guy in the fake Gucci jumpsuit, or the guy in the real Gucci jumpsuit and the Gucci loafers walking his dog to get The Times. Its not just about getting something off the rack: it’s getting it then doing something to it, to add to it, to change it, to customize it. But the idea of customization is something that spreads across all of America, which is: you buy something that is mass-produced and you individualize it. And they caught into that in the last couple years, but it goes back to the Model T in the 30s and 40s.

© Luis Gispert. Burberry BMW, 2011. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

What about the wealthy people who buy these fakes? I mean, you can buy these really good fakes Illegally, and wealthy people who can afford the real thing buy that.

It proves that its absurd to put that much value into a bag. A $10,000 bag? There’s something perverse about that.

But people in the music industry buy it.

That’s different because they’re in entertainment and have to maintain a persona. The rap guys are obsessed with jewelry, but how do you know if they’re not fakes? The knockoffs you see today are the copies of the ones that rap guys get made custom. $150G’s for a bracelet, it’s absurdity. But it was the same in old school rock, it’s the absurdity in the braggadocios, in the showing off. It’s part of the mythology of being an entertainer to us mere mortals. Look at Liberace. It goes back to any form of showmanship.

Look at Versialles.

Look at Versailles!! (Laughter)

Consumer culture is in constant flux. There are new trends that constantly change, while new brands are forged and others reemerge. How do you think your work relates to this constant transformation?

I think when my older work related to pop-culture, that was more closely related to trends, things that were going on and part of the zeitgeist of the moment. More and more i’m interested in themes that are a little bit broader, classic themes that might last longer than a trend. But my work changes, I change, and maybe that ha something to do with my attention span. During every project, I get really intensely enamored with a subject, and I research it, and I live it, and I go out there and I find it and I make it, and then it burns itself out and maybe it just kinda mimics itself in culture. Maybe when I was younger I was more interested in how pop-culture related to art and taste, but now that I’m older, I’m married, bought a place, trying to have a kid, so the world is kind of changing, and more and more I know what I’m interested in. I can say, “Wow thats a real spectacle going on over there, but I have no interest in it”. I’d much rather research something I’m interested in thats already 10 years out of date or passe. But every once in a while, it’s exciting to discover a new phenomenon in culture or say, “who is this new person thats super young making this interesting stuff?” I’m kind of cynical, and really critical, especially of music and hip-hop, and now that it’s an industry, the appropriation and regurgitation and repeating of stuff get boring after a while. Its not even entertaining after a while, so I’m always taken a back by someone who does something interesting.

You use the word aesthetic, and a lot of it is based off people’s socioeconomic level, but how much of it also trying to fit into their peer group?

It’s like a uniform, or something. But I agree with that. If you think of track housing, it’s all cookie cutter, you can’t even pick the color of your picket fence because everyone wants to fit in.

What would you like people to say, or think, or feel when they look at your work? What emotion would you like to provoke?

Mixed. Mixed emotions. When I was younger it was very important for me to have a visceral impact at first; the image, the work, has to be compelling. A lot of my work was between the grotesque and the attractive. Once you get past that initial effect, you’ll stay and scratch beneath the surface because there’s a lot there. The newer work is a little quieter. I hope its still visually intriguing, but it’s not like getting hit with a baseball bat in the base of the neck. But in the end, when you walk away from it, you know its impossible to know what people are going to take away with it. I hope when you pass over the image, you’ll look at it for more than a few seconds. Oh, and something I forgot is humor. All of this work starts from a humorous satirical place. Every time I get into the studio there has to be lightness to it, there has to be humor so I don’t get too self important.

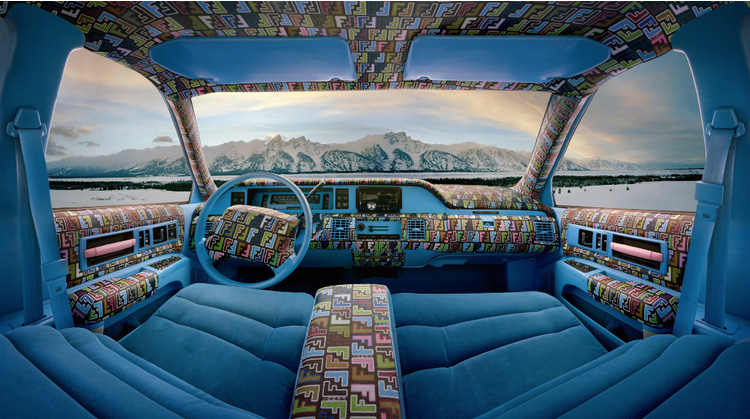

©Luis Gispert. Fendi Caprice, 2011. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Do you think that deflects from the seriousness of your work or how seriously others will take you?

No, I don’t ever think about that, but I think its about making it palatable to me. I’ve always been a joker. I think its part of the accessibility point, so sometimes the humor can be a Trojan Horse to disarmingly allow you into the piece.

How do you feel about people referring to you as a photographer rather than an artist?

Thing is, I went to school with photographers, I know a lot of photographers, and I don’t think they consider me a photographer. I know my way around a camera a little bit but I guess I don’t consider myself a straight photographer. I guess it’s all relative, but I being an artist because I prefer flexibility and I like making sculptures. When I think photographer I think of the Magnum guys. The man on the street with a Leica, the man with a Hasselblad.

Do you think more is being called art now more than ever before?

Yes, yes. More and more every decade.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about your work?

No, we covered humor, and that’s important to me. I’m a sculptor more than a photographer. I’m really not a photographer, I just conceive and idea of an image and figure out a way to put that on film. I love to obsess over stuff. I love to shoot film, even though I’m not a photographer. If I was a conceptual guy maybe I’d have gone ‘oh shoot it digital or why not get stock photography, but I fetishize the process of the camera and film. I must say I’m getting bored with everything being made digitally. I think the younger kids, who are now the ones born with it in hand, are going to turn against it and go back into analog photography.

©Luis Gispert. Sprouse Gouse, 2011. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.