- Source: BOMB MAGAZINE

- Date: MARCH 13, 2019

- Format: ONLINE

Lauren Bon and Oscar Tuazon

Oscar Tuazon, Library Window (LAWS), 2018, powder print on glass, Milgard window, plywood, and aluminum. 81.25 × 23 × 13.25 inches. Photo by Jeremy Jansen. Image courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, and Eva Presenhuber, Zürich and New York.

California’s water crisis has been in the making ever since settlers forced Native people off their ancestral lands and set the region on a rampant path of farming and industrialization. Once this monumental engineering of the landscape had begun, the twentieth century saw no limits to diverting rivers, building dams, reservoirs, and hundreds of miles of pipeline for routing water to growing cities. Today, add climate change, drought, and diminished snowpack feeding the watershed to poor policy, agricultural overdraft, waste, and pollution. Viable solutions, along with a change of public attitude, are urgently needed.

Lauren Bon—artist, activist, and cofounder of the Metabolic Studio—spearheads Bending the River Back Into the City (2018), a radical intervention on the battered LA River, twelve years in the making. For a precursor project, Not a Cornfield (2005–06), the collective laid ninety miles of irrigation pipe, cleansed the soil, and planted corn sourced from and returned to the Native community in the precolonial watershed of Yaangna.

Fellow LA resident and artist Oscar Tuazon opened the doors to his Los Angeles Water School (LAWS) this past fall. LAWS is one in a series of sustainable modular structures designed to serve as spaces for community mobilization and education about water. Tuazon is also known for public sculptures utilizing sections of water pipeline, which allow viewers to physically inhabit the infrastructure that’s normally hidden from sight but makes our faucets run.

Bon and Tuazon first met at a recent event at Tuazon’s LA Water School and recorded this conversation at Bon’s Metabolic Studio a few days later.

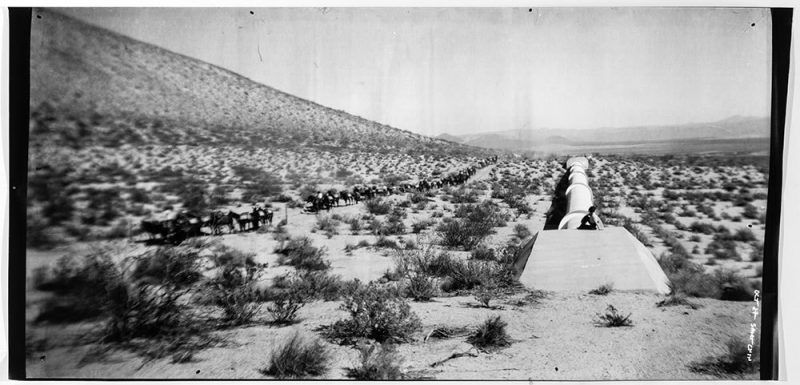

The Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Richard Nielsen, and Tristan Duke), One Hundred Mules Walking the Los Angeles Aqueduct, 2013, liminal gelatin print.

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio, Bending the River Back Into the City, 2012-ongoing. Images courtesy of Metabolic Studio.

Oscar Tuazon

I’m amazed at just how much our interests overlap. You’ve even done some works that I’ve had in my mind.

Lauren Bon

Oh, which ones?

OT

Well, just looking at your bookshelf and your walls, we seem to be working with the same map, literally. (laughter)

The maps might be a good place to start. Mapmaking and drawing on existing maps is something I do a lot; for me it’s a way to zoom in and out to different scales.

LB

I’ve been using my body and my movement between places as a form of mapmaking. With One Hundred Mules Walking the Los Angeles Aqueduct, I walked 240 miles of the LA Aqueduct as a meditation to precede my work Bending the River Back into the City. I wanted to take the time to understand the sacrificial landscape of Los Angeles’s watershed—the space between the snowpack of the Eastern Sierra and Los Angeles. What does this landscape actually look like? The movement of a natural resource from one place to the other—what does that look and feel like? How would the world be terraformed differently if water falling from the sky as snow wasn’t networked in the way it is?

OT

You mean, if it just stayed where it was?

LB

Yes, and if it could again reach the streams and rivers that spread into deltas and eventually fall into the sea. Think of all the living systems that would benefit.

One overriding ambition in the Metabolic Studio projects was to reconnect the floodplain here with the water that used to connect to it. It’s an invention that a river called the LA River existed; there was only a seasonal flood channel. You can find some line drawings of a creek, basically. But what would happen here, where we’re sitting, is that when it rained, it would flood. Which is what made this particular part of the city a place where, for a millennium, Native people would settle. The land here was moister than the surrounding area.

People have been moving water to where they needed or wanted it for thousands of years. What’s new in our era is our entire commons is being challenged. We need to address the air we breathe, the well-being of the oceans, topsoil, and trees, and the sequestering of carbon.

OT

Most maps are bad at representing change and movement over time; they treat space as static, even though water is always on the move. Now you see it, now you don’t. The river might be as much a temporal event as a geographic feature.

LB

Water flow in the arid parts of the world is not easy to understand through mapping because a lot of the flow happens on water table levels below the earth’s surface. It takes a much slower, more deliberate kind of mapping—like moving the body through space. For me it’s been the movement between the basins of the intermountain West, from the Rockies to the Sierra, and understanding what the major rivers of these places are doing and not doing. But tell me about your project, the Los Angeles Water School.

OT

The Los Angeles Water School (LAWS) is a recent endeavor, and it would be hard to tell the story without mentioning Standing Rock. For a few years I had been working at a studio space near the LA River, but I wasn’t really conscious of the river as an entity. It was just this weird concrete channel. I was working on a passive solar structure based on a 1970s design by the architect Steve Baer for his home in Albuquerque. The original structure was built for a particular high desert climate that is hot during the day and cool at night, so the design stores solar energy in a water-filled facade that gives off heat at night. The structure adapts seasonally by opening and closing to the environment, an intelligent system that runs on really basic manual technology.

Over the last couple of years, as I’ve been revisiting the structure, its simple principle—sunlight on water—opened my eyes. Here in LA you can’t look at water without seeing Owens Valley or the Colorado River. These connections are dynamic and alive. At that time, I was also driving to Standing Rock and starting to understand the massive water system that connects North Dakota to the Gulf of Mexico and the vastness of flow across these huge distances.

For an artist working on this scale—which is a continental scale, really—it becomes less about an object; it’s about an environment that people inhabit and pass through. Not to say the process is not an art practice, but I wonder if you relate to the notion that the object can’t possibly encompass this scale or the question that it is a part of.

LB

Yeah, it’s an interesting thing to love space and be a space-maker. I believe the spaces we make are subject to the same laws that govern all form, which dictate that everything is in a state of transition, all the time, everywhere. Artists are needed now as big-systems thinkers. Human survival is at stake, and we should claim our mantle as free agents and propose outside-the-box methods to support the life web. In the works I make with the Metabolic Studio, catabolic and anabolic processes are at the core of the practice: things that get torn down and things that build up. The objects I make are meant to be catalytic, systemic works that are not about their own formal elements, but instead are catalyzing formal elements in a kind of prophetic challenge.

OT

So along with a vast physical scale, the work also occurs over a very extended time.

LB

Exactly. We don’t focus on the now but on the becoming. Every place is the story of its own becoming. How can an art practice catalyze a generative story in today’s world? How do we catalyze a parallel narrative about LA River revitalization that isn’t about stuff but about systems? Bending the River Back into the City is asking, “Why are we so obsessed with a construction from the late 1930s that isn’t even where the river was? Why are we all talking about this concrete jacket as if it was some holy river from the Bible? Why aren’t we instead discussing what the wasted water in that concrete jacket can do if we redirect it?”

Bending the River is about lifting a small part of water up out of the LA River, cleansing it, and redistributing it to two different floodplains to start with—the state park where I started my practice with Not a Cornfield (2005) and the new park across the river of Albion. Both parks will be getting one hundred percent of their water from the Bending the River project and won’t have to pay for water anymore. Our demonstration project is anti-object in the sense that all of this effort is about two small holes bored into the side of a concrete jacket. The result is that water can flow by gravity under the railway tracks and then it gets picked up by a water wheel by its own force and sent through a wetland to be cleaned adequately to meet Title XXII, which is the code for recycled irrigation water. We’re talking about thirty-two acres in the state park and twenty-some acres in Albion Park—over fifty acres of floodplain that will be reconnected by two small piercings.

Now, that might sound like a really large undertaking, but compared to what we’re up against, it’s less than a drop in the bucket. It’s taken a very long time to push through the bureaucracy—there are sixty federal and state permits we’ve had to get, and there’s still one outstanding, which we’re hoping to get in the next few months.

OT

That’s exciting. And it’s important as a demonstration of how an art project can engage directly in the decision-making process of a city.

LB

It’s all about the dialogue needed to make incremental change. It’s a demonstration of an adaptive reuse of infrastructure, which could be much more transformative if it is replicated up and down the LA River channel. Reconnecting the river and the floodplain will make the water cleaner, the soil stronger, and allow us to grow trees that sequester carbon, give off oxygen, and cool our environment. The trees are the real payback here. But we’ve also been able to catalyze some micro-shifts in the park management through water-sharing agreements with the state and city parks: toxic pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides will no longer be used, meaning that cleaner water will return to the water table. Those contractual agreements are crucial returns of the engagement, as opposed to formal things—

OT

Which is so interesting because, as you said, the form itself allows this pragmatic shift to happen—

LB

Yes, it’s a critical part of the conversation—

OT

Right. There’s this utilitarian role of the artwork, which is this beautiful paradox that I’ve tried to work with myself. How to make a functional artwork? I think it works as a circle—when the artwork creates something, like clean water, or the growth of new trees, it’s a process that then generates something outside and beyond itself. I mean, was William Mulholland actually an artist? The Los Angeles Aqueduct was a kind of absurd earthwork.

LB

I think Mulholland did what anyone in his position might have done at the time. He was trying to solve a problem, which was that Hollywood had allowed the city of LA to grow quite large. As it continued to grow, it maxed out the Zanje Madre system of ditches that were here before. Mulholland’s engineering of a large-scale water-supply infrastructure was part of our federal government’s plan to make our country an empire. This meant colonizing the West and making it boom the same way the East Coast did and, simultaneously, opening up the West Coast for international trade with Asia.

OT

All of which resulted in reengineering the environment.

LB

Controlling the seas and rivers. Mulholland’s plan was only made possible by Theodore Roosevelt. To get the water flowing, he signed the 1906 law that provided the land necessary to build the LA Aqueduct. All territory around our water supply was either federal or state-owned. The park system allowed the trains to come across. And while Roosevelt was doing that, he also masterminded the Panama Canal, which opened the year after the aqueduct. Both were part of a grand masterplan of American capitalism and the maturation of Manifest Destiny.

But the LA Aqueduct didn’t do anything that hasn’t been done for millennia. We tend to think about historical treachery rather than seeing what happens every single year that we continue to take water from the Owens Valley. Finally, in 2018 water limits were enforced for Mono County ranchers. There’s a big battle right now for that landscape, another territory sacrificed to the city of LA. In that light, Mulholland is way less problematic than the current absence of civil dialogues about our water sources and the real costs of our appropriation of water, including the wild fires in the West, dust that’s getting into the atmosphere…

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio, Bending the River Back Into the City, 2012-ongoing, Los Angeles Watershed.

Lauren Bon and the Metabolic Studio, Reimagine Payahuunadü, 2017-ongoing.

OT

True. And as artists we can extend our own perception and understanding of water here in the city and in Mono County, where our water comes from. We need to reflect on the space we each occupy as an individual body. We can do that by walking alongside the water, or even by walking through a pipeline. When I installed water pipelines as public sculpture, I was superimposing those two scales—the individual and the structural. I’ve seen how physically experiencing the infrastructure above ground enables people to conceptualize these systems on a human scale.

A process like yours, and mine too, is inherently collaborative. Once you start to engage with a natural system like water, you immediately recognize it connects us all. And because water is so intrinsic to life, it’s a medium for bringing people together. This became very obvious at Standing Rock, where issues related to land and public water were articulated in a very clear manner due to the crisis. For many people, the interconnectedness of all systems, natural and infrastructural, was brought to the surface for the first time.

LB

When authorities want to end an occupation, they cut off the water supply and that pretty much ends any protest. Water independence is a portal toward independence from all kinds of things we might need to become independent from. Which are the very things we take for granted as part of urban life—you get a place and you pay a fee and you get water; you pay another fee and you get electricity. We don’t have to think about sourcing these necessities and therefore have more time to do other things. But what happens when these systems aren’t working? Very quickly we’ve left behind the knowledge and skills of our ancestors, who used to teach us how to source water or make power. Now we’re reduced to being children of bureaucratic agencies. They can put a stop to everything we know how to do the moment our electricity and water grids shut down. And we see how fragile these grids are, even in moderate wind storms or rain events. Those things are truly alarming to me. What makes us believe so strongly that these things are sound? And here in LA it’s like the ultimate absurdity: we’ve got ten million people and growing—

OT

And everyone’s waiting to turn on the tap, assuming the water will be there.

LB

Amazingly, Mulholland’s aqueduct made sense for a long time. From 1913 into the ’70s, water was supplied to LA for almost free, so people were racing to this great climate from everywhere. The LA Department of Water and Power was considered a heroic agency, and it produced exhibitions and a monthly newspaper that everybody got. They staged cultural events: in the ’50s, once they realized the Hoover Dam was going to provide so much electricity, they had demonstrations of what it meant to be modern—“Stop using your gas stove, go electric!” Their PR machine was sophisticated; it worked for decades. And when we say it worked, part of that was making it seem like we no longer had to know how to do these things for ourselves. Look at Manhattan: one hundred percent of its water is imported from somewhere else. How many people do you know in Manhattan who would do well if there was no more water supplied to them? Look at the Great Lakes and Detroit with the water shutoffs that are going on. That’s a place with a lot of water! So why aren’t there more alternatives to bring water to places with water shutoffs?

OT

We need to be more intelligent about using water and make our water use more tangible. The solutions should be hands-on, human-scale responses to our changing climate. It can be done. The type of heroic infrastructure projects we mentioned are unsustainable in the long term.

LB

They are very paternalistic! The conversation you hosted last Friday at your Water School was very important. Listening to the circle of Tongva women talk about water, specifically the absence of those LA hot springs that have been covered over, made the situation really tangible. This loss of natural mapping comes with the loss of stories about these places.

OT

And there’s lots of individual knowledge that supported and sustained those water sources. Elder Julia Bogany has been instrumental in the Tongva language revitalization project, and to me it’s incredibly important to know the names of the villages sustained by this river for thousands of years. Language is an enormous cultural resource that can teach us where water is, where it comes from, how people move through and with the water. The ancestral knowledge of the Native communities and the individual agency that comes along with it is valuable to all of us: knowing where and how to get water—

LB

And knowing seeds.

OT

Right. Developing relationships and responsibilities to living systems continues to be an ever more urgent necessity in the era of climate change. We can learn from successful environmental management strategies of Native communities.

LB

They say it takes two generations for those stories to be lost altogether. Native people’s stories are essential to us all. I thought about some of the questions during the LAWS event, like, “What do we do about oil drilling off the coast?” The reality is that most of the oil we run our cars on here in LA comes directly from the Amazon. We are the direct consumer beneficiaries of the exploitation. The Amazon makes up the lungs of the planet. So how do we decide where oil drilling is the least bad?

OT

We have to think on a global scale.

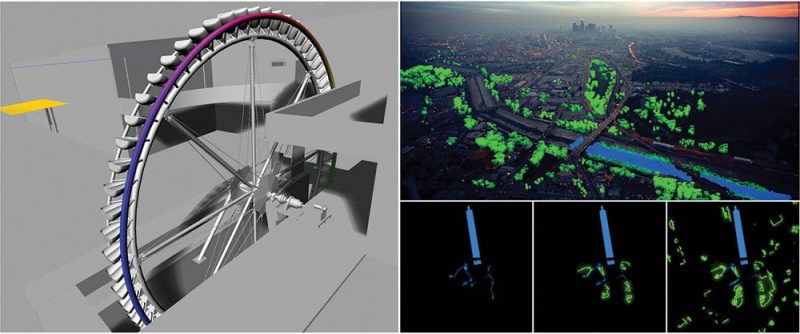

Oscar Tuazon, construction view of the Los Angeles Water School (LAWS), 2018.

LB

The tribal narratives that have been lost need to be found and reconfigured so we can understand the interconnectedness of all living things. The local stories wouldn’t have sufficed to meet the reality of global warming, but they still could have stabilized local patterns of sourcing and resourcing our lives. We should at least have accessible knowledge about how to behave if we needed to survive.

Even socially, we assume we don’t need each other for anything more than the interior narrative of our lives. If we didn’t have water or heat, we’d probably be better kinds of neighbors. Thanks to domestic utilities and global markets supplying us everything, we forgot how to form relationships with people with multiple skills. Metabolic Studio as a practice is about joining forces and exhibiting—as a full-scale model—that another city is possible.

OT

Artists are able to model systems.

LB

Yeah. I’m trying to work with people who bring different skill sets to the table, including the capacity to build trust in a traumatized part of town, especially around real-estate trauma. This requires staying put, keeping at it, and becoming known as a neighbor. Most artists come into a place, do a project, and then move onto the next endeavor—

OT

—wanting to maintain a certain invisibility or site-lessness. As you said, building real relationships with other people is key. Maintaining relationships with the natural world and people over time are at the core of the Tongva stories and they are vital to any kind of community, regardless of its size. For instance, knowledge about water doesn’t exist in any one person or place, it lives on in those cross-generational relations. I hope that LAWS can continue to be useful to the community in that way.

LB

I read a bit about your background. Your parents were people who made communities. How has that experience affected you in terms of relationship building, homesteading, and resource sharing?

OT

I would say that the core of my work comes from architectural or spatial ideas. My parents built a geodesic dome and I was born in it. My current work marks a shift from the private house to a public structure in a literal way. The building I based the design of my public structure on was Baer’s one-family home. I took that structure as the DNA and blew the domestic part out of it in order to design a public communal space. I’m just starting to understand the implications of that—it’s exciting to invite other people in! For our first public event the other night, we had fifty people in what originally were a couple of bedrooms.

LB

So, the structure we were in was exactly like Baer’s house?

OT

It’s one part, actually a quarter of it. Having grown up in a geodesic dome, it’s this weird dream object for me, but I’ve also found it problematic because it is an emblem of white flight and the death of the city, as it was known at the time. I’ve always had questions about urban retreat, and, in that context, I have a nuanced relationship with Baer’s work too. The Water School in LA is my attempt to reimagine what a house can do in an urban environment now. The passive solar concept Baer was experimenting with has real applications for building in an ecological way today. It was particularly important to push away from the domestic and toward the notion of community.

LB

You’re taking something that, back then, represented a new way of domestic existence, and while you’re appropriating aspects of it, you’re changing its architectural brief from one about the nuclear family to one about tribe. About where we come together to explore in a bigger group, one that is self-appointed rather than based on biological engendering.

OT

Right. And this structure, as we rebuild it, will eventually exist in four different locations—here in Los Angeles; Minnesota; Michigan in the Great Lakes area; and Nevada, in the Great Basin area along the Nevada-Utah state line, where the Water School will ultimately be reassembled as a public space in a remote place. The structure will be linked to each of these four places, and to the water systems that connect them. It will become a school network that can educate us about water, and show us how water moves.

LB

Have you chosen these locations because they’re nodal on different watersheds?

OT

Yeah, but in a way, they’ve chosen me. I was drawn to Minnesota by Winona LaDuke, who has articulated so clearly how local struggles for clean water are part of a much larger, existential conflict, one that we all participate in. Tribal nations have a strong track record of being good environmental stewards on behalf of all of us. The message at Standing Rock was: Oil and water don’t mix. The tension between water and oil there is continual and urgent, and Winona’s organization Honor the Earth has been at the forefront of the resistance to the environmental catastrophe of tar sands extraction. The Dakota Access pipeline is one vein of that, and Enbridge Line 3, which threatens the Ojibwe water system, is another. This is where the Mississippi River originates; this water touches all of us. It belongs to all of us. So it feels important to be there and create a space to support this work that could perhaps participate in local water politics, but also, as you said, to acknowledge the space in between places and to articulate, even model, how water connects people over great distances. To make that connection between LA and the White Earth Nation in Minnesota helped me conceptualize what it means when we say that water connects us all.

What I hope to do in Nevada is reunite the sections into a single structure and create a Water School that will exist as a new type of architecture. I’m envisioning a public space that could consolidate activities already underway in this area. In this arid high desert environment, all the water is groundwater in aquifers. The land I’m working with is on the Goshute Aquifer, a site where the Southern Nevada Water Authority is attempting to build a 300-mile pipeline to pump groundwater to Las Vegas. For nearly twenty years, a broad opposition to the pipeline has successfully resisted an environmental devastation on the scale of what happened one hundred years ago in the Owens Valley. I want to contribute to that complex and fraught dialogue and create these environments, not as my own artwork or architecture, but to provide space for others to act—almost a stage for other people to claim agency in this conversation around water that affects us all.

Oscar Tuazon, Water Map (Goshute Aquifer, Spring Valley, NV), 2018, India ink, watercolor, marker on paper, 24 x 36 inches. Photo by Farzad Owrang.

Oscar Tuazon, Rainwater, 2017, part of Une Colonne d'Eau, installation at Place Vendôme, Paris. Photo by Marc Domage.

LB

Have you purchased the land?

OT

In Nevada, yes. And the Water School in Minnesota is a guest on a permanent site.

LB

You’re making permanent offerings.

OT

Yeah, the idea of a gift economy is very appropriate. Winona’s work is driven by generosity, and her work to protect clean water benefits all of us. I hope that, in turn, the Water School in Minnesota can serve the community on the White Earth reservation.

LB

Will each of these places be completely free to emerge in whatever way they emerge over time?

OT

It’s hard to say. I think what they will become is beyond my control. I’ve been part of a process and now, particularly in Minnesota, other people will play the main role. I want to facilitate and create a space that is useful to the work Honor the Earth is doing. A school starts with a library, and I hope it can grow into a useful resource.

LB

And is Los Angeles Nomadic Division part of this?

OT

Los Angeles Nomadic Division (LAND) is the programming department here at LAWS. LAND is a great partner because they have experience commissioning public artworks and are active in spaces throughout the city. We are organizing a monthly series of conversations around water, where a diverse mix of people can come together to participate in the discourse.

The lot where I’m building LAWS doesn’t belong to me, but putting down roots and staying in this place is a crucial part of the practice. We’ll see what happens.

LB

Boyle Heights, where LAWS is located, is a highly politicized space.

OT

There has been very productive critical discourse in the neighborhood. Originally, I had this massive studio space that I was using to produce my own work. At some point I had to ask myself, “If I’m going to do something with my limited resources, what do I really want to do and how does that relate to my neighbors?” The Water School has grown out of thinking about what role artmaking can play in building community and culture. It’s an interesting time to be working in Los Angeles and engaging with these issues around water. The stakes are real—they’re biological and political, and I feel alive to my own agency. That’s something that came from Standing Rock, which was, as we know, this mass outpouring of people with the least agency taking power. And that power hasn’t diminished; it’s grown. It feels like a candle, you know? Many of us are keeping that flame alive.

I was looking at the logo of Metabolic Studio and thought, Wow, there’s another connection. My logo is a bird too!

LB

Which one is yours?

OT

It’s a crow. My daughter drew a crow, so it became the figurehead.

LB

I love crows. Ours is a roadrunner because it’s the only bird that can scavenge water from its own feces. That’s how it survives in the desert—sticking its beak up its bum! (laughter) I thought that was the perfect emblem for our water project.

OT

That’s what it takes.