- Source: Frieze Magazine

- Author: IAN BOURLAND

- Date: June 14, 2021

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

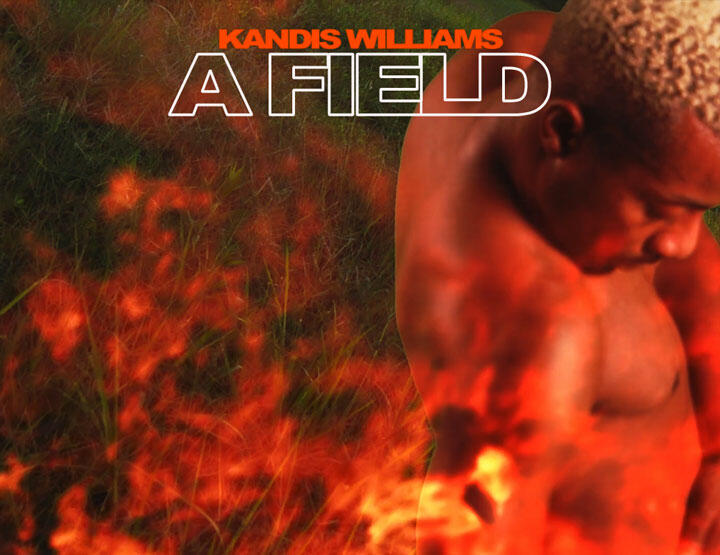

Kandis Williams Unearths the History of US Extractive Labour

At the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, the artist presents a site-responsive project that looks at the fraught history of post-slavery labour practices across the Virginia countryside

'Kandis Williams: A Field', 2020–21, exhibition view, Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Courtesy: the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University

In 2016, I reviewed a group show at the Studio Museum in Harlem – ‘A Constellation’ – and found myself utterly captivated by a mixed-media piece by a young Baltimore-born artist named Kandis Williams. That work, paralysis II (2014), overlayed photographic fragments of young women embracing, registered over a series of monochromatic, angular motifs. It called back to historical tensions between photography and painting, abstraction and figuration, and resonated on a haunted frequency – one refracted through a then-au courant glitch aesthetic. It also seemed like an opening salvo, a foundational gesture towards bigger things on the horizon.

'Kandis Williams: A Field', 2020–21, exhibition view, Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Courtesy: the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University

Last autumn, Williams installed a site-responsive project, A Field (2020), in the upper gallery of the ICA at Virginia Commonwealth University. Elaborating her earlier experiments on a grand scale, the work addresses a vast historical sweep without sacrificing a feeling of immediacy made all the more potent by its contrast with the screen-bound textures of most COVID-19-era interactions. The gallery – an airy, vaulted white cube – had been transformed: when visitors exit the elevator, they are greeted by a sense of lush overgrowth, more evocative of the region’s tidal marshes, kudzu and dense forests than the Richmond streetscapes beyond. Faux banana leaves and abundant fronds sprout from elongated vases of black water; others form a canopy over a makeshift trellis. Closer inspection reveals low-res images on the leaves’ versos – found photographs from mid-century magazines, fragments of pornography, scenes of men working the chain gang and portraits of the 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass. These elements are echoed on five elongated banners encircling the space, while patches of turf dot the walls like canvases.

In this way, Williams creates a dissonance between moribund archival images and botanical vitality, between inheritance and becoming. The scene is anchored by an inviting expanse of green, framing a small shed. Within, the titular video plays on a loop, reverberating the sinuous minor key of the tango – a dance made famous in Argentina but, as the wall text notes, originated in Río de la Plata, on the Uruguayan border. The dance was brought there by enslaved people – its pas de deux an analogue for the collisions of peoples through which the Americas were forged. On one level, A Field is a passage through the Virginia countryside: aerial views of an expansive, exurban manse are followed by scenes of the bucolic Tidewater region in Norfolk that was once home to plantations and, more recently, prisons where inmates were sentenced to hard labour. Finally, the terrain seems engulfed by fire, burning all to ash and, presumably, on the cusp of a new cycle of regrowth. Throughout, the superimposed figure of the dancer Roderick George moves rhythmically, at times embracing a spectral twin.

Kandis Williams, Annexation Tango (video still), 2020.

Courtesy: the artist and Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University

Such scenes of dialogic encounter elaborate the project’s underlying motif of a shared modernity that is fundamentally relational, wherein there is no self without other, no America without Africa. But, in responding so clearly to Richmond itself, Williams also draws important parallels between the foundational moments of extractive labour in this country, and its persistence by other names – a crucial invocation at a time when many states aim to enact repressive voting laws that land heavily on people of colour. By re-iterating the eastern seaboard as part of wider Gulf or Caribbean imaginary, she also calls to mind such landscapes as places of simultaneous trauma and abundance. While the former is never fully out of the frame, Williams postulates Black futures unbound by the strictures of the hothouse, and free to effloresce.

‘Kandis Williams: A Field’ is on view at Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University through 12 September 2021.