- Source: ARTNET NEWS

- Author: NATE FREEMAN

- Date: OCTOBER 29, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Just in Time for Trump’s Impeachment, the Watergate Is Back in the Spotlight—as a Place to Show Contemporary Art

What better place for an exhibition about conspiracy and political malfeasance?

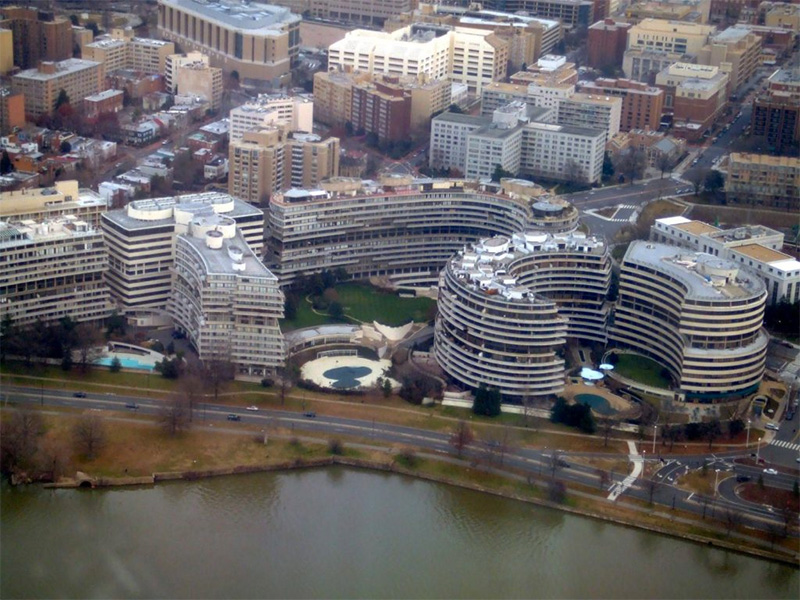

The Watergate complex.

There’s a prevailing notion that Washington, DC, is a one-industry town beset with bloodthirsty lobbyists, ambitious Capitol Hill aides, White House employees cashing fat checks and walking through a revolving professional door, and cutthroat Supreme Court clerks fresh from Harvard Law—and that’s just during a normal administration. I grew up in the area, and I can tell you that such a reputation is… well, it’s basically correct! And yet, it has a history of producing artists of true genius, such as Morris Louis (born in DC in 1912), who alongside fellow Washington resident Kenneth Noland pioneered the Washington Color School. More recently, the artist from the city who’s had perhaps the most outsize influence on a new crop of artists is Kenneth Noland’s daughter, Cady, who was born in Washington in 1956. And now, decades after Noland stopped making work (she’s long maintained a Pynchon-level disappearing act and is said to be holed up in a fifth-floor one-bedroom apartment west of the Flatiron District in New York), her work returns to DC for a show in a location that fits her obsession with the conspiracy theories and political malfeasance: The Watergate Complex, the iconic half-circle riverside series of apartment buildings where a break-in brought down a president, and where prominent swamp-dwellers such as Karl Rove, Bob Dole, and Alan Greenspan all lived at one point or another.

Works by Cady Noland, Dahn Vo, and Sondra Perry in the exhibition.

The two works by Noland are in a show organized by Tribeca’s Bortolami Gallery as part of its Artist/City project, wherein an artist is invited to make use of an underappreciated aspect of one non-New York city. Previous iterations have handed the reins to artists on the Bortolami roster, but for this edition, gallery founder Stefania Bortolami wanted to work with artist Paul Pfeiffer, who instead of accessing his own works decided to curate a group show with artists he had long admired. Titled “Exodus,” the show relies on work by Noland as well as Josh Kline, Cameron Rowland, Sondra Perry, Lorraine O’Grady, Dahn Vo, Eric N. Mack, Renee Green, Arthur Jafa, and Lutz Bacher. In a press release, Pfeiffer explained that he wants the show to comment in a broad sense on migration—physical migration on land, but also the migration of a readymade from object to artwork. If the timing seems almost too on-the-nose—a deeply political show in the nation’s capital, in the heart of the Watergate, as President Trump faces an impeachment threat, and with the Washington Nationals playing the first World Series in DC since the 1930s—it’s interesting to hear that the exhibition has been in the works for years. “The list of artists has been formed for a long time,” explained Emma Fernberger, who is the Artist/City director at Bortolami. “But the political moment that we’re living in, as time has gone on and this conversation has progressed, it seemed more and more urgent.”

A work by Josh Kline.

We were speaking last Sunday morning in the Watergate space, the day after the evening opening. It had been an eventful night. In addition to Bortolami hosting a lovely toast-filled dinner nearby, the Nats got drubbed by Astros just over three miles away by the Anacostia River, and Trump watched from the White House situation room (or from the back of a golf cart leaving his country club across the Potomac, according to a pool report) as American commandos killed ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Fernberger explained that the gallery space had once been a PNC Bank branch with a metal vault (it’s still intact), and as I walked around, the familiar scene of Foggy Bottom peeking out in the background (my late grandmother had lived in the Watergate) took on an eerie quality in a building so associated with abuse of executive power. It turns out to be an unexpectedly great space to show art, hinting at a potential art-centric future for the centrally located, globally iconic Watergate. Could its spiffy Watergate Hotel—which opened within the complex in 2016 with the self-aware slogan “no need to break in”—be the choice venue for a Washington DC art fair, in the vein of new suite-based expos such as Felix LA and the NADA Chicago Invitational? Either way, “Exodus” will be a hard act to follow. The show ended up in the Watergate instead of in Atlanta, where it was originally going to be, because of a random connection to the curator Owen Duffy, whose brother was a former property manager of the Watergate space. After finding out there was a vacant space available, Duffy got in touch with Bortolami Gallery about the possibility of a DC Artist/City. “It was too good an opportunity to pass up,” Fernberger said. “We pretty quickly came down here with Paul and he was like, ‘Oh my god, this is incredible.’ And it fit thematically with what we were already envisioning. It was kismet.”

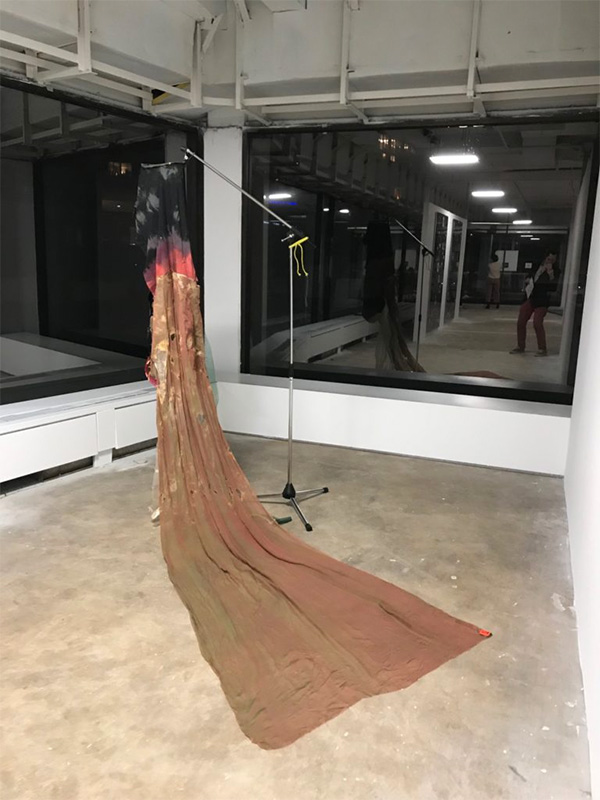

A work by Eric N. Mack.

The exhibition is a gorgeous, brawny critique of our nationalist fervor, staged in the heart of a government center that’s been infected by it, with top-notch examples from some of the most exciting artists alive (though, sadly, Bacher died in May, as the show was being finalized). Noland’s chain-link fence sculpture, Institutional Field (1991), was recently shown at her acclaimed retrospective at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, but it gains a new power here at the Watergate, blocks away from the White House, where policies are being drawn up that rip children from their parents at fences that exist across so much of the country. Elsewhere in the show, Kline’s video Crying Games / Financial District Display 65” (2015) makes reference to one former Watergate resident, former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and two of Vo’s works explicitly reference another: Robert McNamara, the Vietnam War architect who died in his sleep in his Watergate apartment in 2009. One Vo work, Walnut Lumber (2019), is a pallet of wood taken from orchards owned and maintained by Craig McNamanra, Robert’s son, who invited Vo to visit after hearing of his fixation with his father. One aspect of that fixation is Vo’s habit of buying McNamara memorabilia in online auctions, and the other work in the show, Lot 19 Test Ban Treaty Signing Pen, 5 August 1963 (2013) is the tip of the pen used by McNamara to sign the Test Ban Treaty—an object that was sold at Sotheby’s. Bacher’s Whiteboard (2018) makes references to the Tet Offensive and the Mai Lai Massacre amid a bunch of semi-inscrutable doodlings. There are also photo collages by Arthur Jafa and a series of photographs by Lorraine O’Grady that show a performance from 1982 that took place in Central Park, and an elegant draped fabric work by Eric N. Mack that’s installed on a stand, catching the curved shadows that come off the S-shaped building as the sun goes down.

The Watergate from across the street.

Bortolami told me that the show would hopefully draw in government workers and other big shots in politics who might not have time to make contemporary art a regular part of their cultural consumption—even if the local gallery scene has been beefed up by arrivals such as the Georgetown space started by former Team gallery director Todd von Ammon. And Fernberger reached out to some of the more well-known policy makers in the area as well. “I wanted AOC to come, and the squad—I really wanted the squad to come,” she said. “The idea of exodus deals with immigration, and that’s a pressing issue that these politicians are addressing the best they can.” And it’s a distinct possibility that Foggy Bottom’s most prominent tenant—the State Department—will at least notice that there’s something unusual going on in the old bank space as they run out to grab sandwiches at the deli downstairs or cocktails at the swanky hotel bar. It would be hard for them to miss it. But one visitor that Fernberger is not counting on is Cady Noland. Though the artist sometimes comes to personally install works at shows via an arrangement where someone leaves her the keys and lets her install in complete solitude, in this case, she was sent emails asking whether the works were installed correctly, and responded with small requests, indicating that one work had to be flipped, and another needed to be moved a few inches. The famous recluse may not be coming back to the city where she was born, but apparently she’s a very prompt emailer.