- Source: Out Magazine

- Author: R. KURT OSENLUND

- Date: March 10, 2017

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

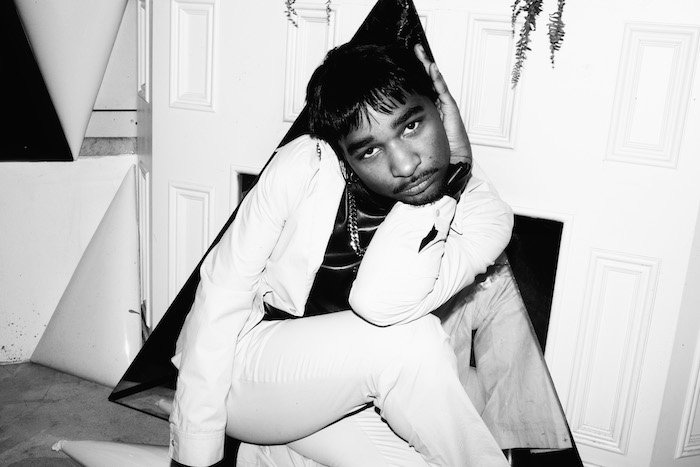

Jacolby Satterwhite Evokes Queer Spaces of Every Kind in Epic Tribute Album to His Late Mother

The multi-faceted artist reveals the story behind his most personal work yet.

Photograph courtesy of OUT Magazine

Squeezed into a prop-riddled balcony in Brooklyn’s Spectrum dance club (or Dreamouse) on Wycoff Avenue, Jacolby Satterwhite is defying the laws of nature. Donned in vintage clothes that loosely hang on his nimble limbs, the artist is rapidly contorting his body into different pretzel-like poses, eventually holding one as he sinks into a pile of faux-fur pillows and garbage bags. While some might call it eccentric, the whole tableau is in fact quite minimalistic for Satterwhite, who previously, as seen in the pages of OUT and in exhibitions around the globe, has performed in spandex bodysuits covered with androgynous protrusions and digital screens. “I’ve moved away from that for a couple of years,” Satterwhite says. “I think right now I have a different message. My work is still gonna be 3D-animated and otherworldly and weird, but lately I feel much more satisfied with the conversation I’m having with my audience—it’s about tactility and connection. I think it’s more about realism for me.”

While grounding his personal aesthetic in something more real and accessible, Satterwhite, 31, has also been crafting his most intimate and revealing project to date. On March 17 through 19, at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, he’ll be debuting a full-length visual album directly inspired by his mother, the artist Patricia Satterwhite. A homespun, yet modernized labor of love and grief, the album, accompanied by dystopian, cybersexual video elements, features Patricia’s original vocals—pulled from cassette tapes she recorded herself in the ‘90s—and marries them with pulsating techno production by Nick Weiss of the electronic duo Teen Girl Fantasy. “She recorded the vocals in a mental hospital and at home,” Satterwhite says of his mother, who began developing schizophrenia when Satterwhite was 7, growing up in his hometown of Columbia, S.C. “She had a gospel voice, and her songs sound like variations on a standard Top 40 hit. She’d tap a pencil on her thigh as a metronome, which also became an instrument. So that’s the analogue part.” Satterwhite’s collaboration with Weiss, he says, incorporates an acid house style evoking early ‘90s dance music by DJs like Mr. Fingers and Lil Louis.

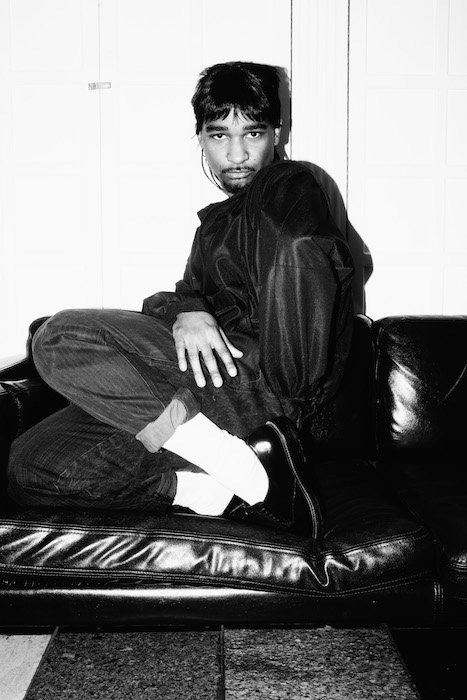

Photograph courtesy of OUT Magazine

“She’ll always be the gesso to my canvas,” Satterwhite says of his mother, whose influence has permeated Satterwhite’s art for years, and whose own work, particularly her drawing, has itself been celebrated—written about in The New York Times and Art Forum and placed in permanent collections at the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Fort Lauderdale Museum, and Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art. But she’s never been such an explicit part of Satterwhite’s palette as she’s been on the new album, which Satterwhite has been producing for the better part of two years, all while showing at venues in New York, Seattle, Dallas, London, Berlin, Oslo, and more. Patricia died last August at 66—something that, until now, Satterwhite hasn’t even told some of his closest friends and collaborators. “It was the hardest thing I’ve probably ever dealt with,” Satterwhite says. “It felt ambient and all-consuming—it could shift my behavior and slow down my process and my work. It was especially hard going to the funeral and feeling that she still seemed so needed. No one else in her immediate family knew how much of a public mark she was making with her work. It felt like people were scrambling to find a record of what made her great, and that really hurt. It made me more determined to revive that voice.”

In terms of just how he would revive it, Satterwhite has dipped into a dense catalogue of artistic, musical, and even familial inspirations. When discussing conceptual sources, the queer vanguard cites trip-hop artist Tricky, who similarly merged female vocals with music he produced, and whose debut album, 1995’s award-winning Maxinquaye, featured a narrative fueled by his own mother’s death. Regarding the creation of a visual album, Satterwhite’s impetus precedes any recent efforts by Beyoncé. What influenced him most was the 2003 Japanese-French animated musical Interstella 5555, a direct visual manifestation of Daft Punk’s second studio album, Discovery. “I was 14 years old, and I was like, ‘Oh fuck—I like the way they packaged that album,’” Satterwhite says. “And ever since I started making my experimental films, I’ve been wanting to make this album in a similar style.” (Indeed, as shown below in the video for the track “Healing in My House,” premiering online as an OUT exclusive, Satterwhite has made good on his goals, creating a 3D dreamscape in step with the work that sparked his adolescent imagination.) As for the acid house homage, Satterwhite attributes much of it to time spent with his two older brothers, both of whom are also gay, were involved in dancing and fashion, and were exposing Satterwhite to the club scene at an early age. “My brothers are 14 years older than me,” he says, “and they’d go to a lot of amazing clubs in New York City and Atlanta, sometimes bringing me along and breaking me in. Even when I was home, there was constantly house music playing—they would almost only listen to mix tapes they got from clubs.”

Partly due to the objectification that he and so many other black performers have experienced, whether onstage or in front of a canvas (he even opted to leave painting behind because of its pressures and implications as “a western white person sport”), Satterwhite prefers not to focus on himself as a black artist. He is adamant, though, in conveying a message of queerness (or, more broadly speaking, otherness), and if there’s one theme holding his new maternally-inspired artwork together, it’s the notion of safe space, in every sense of the term. His exposure to queer club spaces has had a definitive impact on him (the video for “Healing in My House,” for example, was partly filmed at the previous Spectrum location, on Montrose Avenue in Brooklyn), but that’s just one entry point—the most literal—into Satterwhite’s spacial philosophy. He says that Patricia’s songs have an arc to them that speak to his theme, with his mother singing in the space of a mental institution, then at last settling into the space of her own home, not to mention the space, so to speak, of her own mental condition. He even goes so far as to invoke the Afrofuturist movement, which has historically involved black people finding safe spaces for their bodies beyond this world.

Photograph courtesy of OUT Magazine

“Because it has been raked into my subconscious since I was a teenager,” Satterwhite says, “I think that no matter what I do I’m aware of metonymy and the codes associated with bodies, genders, races, mental illness, outsider, insider—I’m aware of what queerness really is. Queerness for race, queerness for everything. I feel like that’s the ultimate overarching basis of where my work operates and functions. It’s heavy, it’s hard to describe, and it’s something I’ve been thinking about my entire life. I was born and raised by a mentally ill woman who was in a mental institution, I had two gay brothers, and I had a heavy involvement in nightlife since I was 13—all of these safe spaces, alternative space. That’s why I did a galactic-looking visual 3D film. All of this is like a metaphor for the safe space that I only understand being someone who was constantly externalized.”

And the space at San Francisco MoMA, where the album will premiere, will echo these ideas. Satterwhite describes the event as a visual listening party, where cellist Patrick Belaga, an integral part of the album’s creation, will also perform. After the inaugural exhibition, Satterwhite will take the show on the road to other venues, before officially releasing the film and finalizing album distribution. All told, the process will be one of continued healing. As Satterwhite tells it, Patricia, who was able to hear some of his and Weiss’s tracks before her death, used her own music to cope, much like acid house music emerged as a coping mechanism for queer people living through the AIDS crisis. And Satterwhite himself has been able to cope, too. “I feel like I’ve had the darkest, but most educating time of my life in the past two years,” he says. “It’s definitely matured me as an artist. I feel like this work is extremely revealing about who I am, where I am now, how much I’ve grown, what I’ve seen in the past, what I’m seeing now, and what I may see in the future. I think it is gonna allow the viewer to really understand me—it’s gonna be less vague of what her significance is in my endeavors. I’m feeling like I’m finding form again after her death. I’m feeling back to life again—finally.”