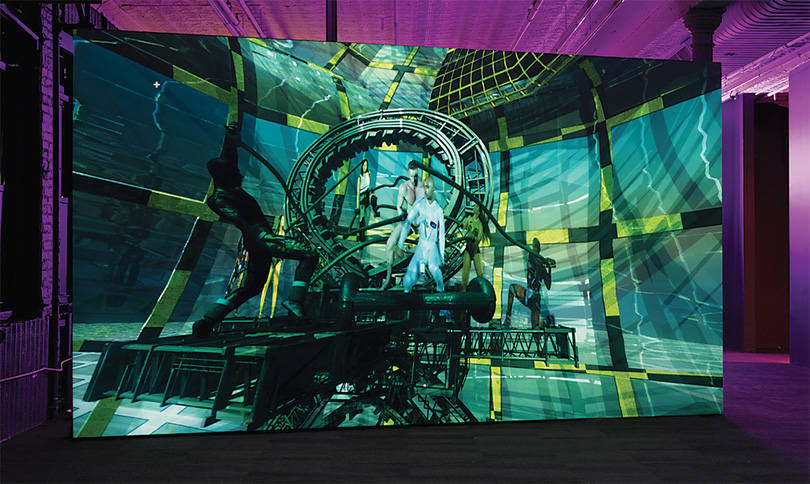

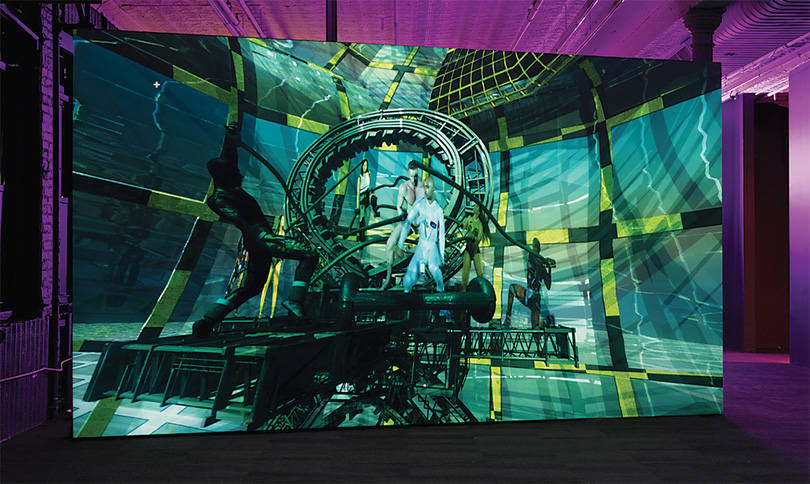

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue, 2018. 3D animation and video, 19:20. Edition of 5 with 2 APs. Courtesy Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/ Rome.

In his essay written for the exhibition, art historian Jack McGrath interprets the store as a gesture of recompense. Pat’s gift shop, he writes, “leverages a son’s cultural capital to drive the economic circuits from which his parent was systematically excluded.” But the store also suggests a second, more fraught reading. Satterwhite’s mid-priced editions honor his mother’s creations while they anticipate and lean into the commodification of alterity that conditions the reception of her art and, in a different way, his own. “No matter what I do, I’m aware of metonymy and the codes associated with bodies, genders, races, mental illness, outsider, insider,” Satterwhite has said. “I’m aware of what queerness really is. Queerness for race, queerness for everything.” Despite superficial appearances, the queerness of Satterwhite’s art isn’t heterotopic or carnivalesque. Like that of its cyborg libertines, Blessed Avenue’s power flows in a feedback loop between reification and subjectivity, alienation and jouissance.

—Chloe Wyma