- Source: Influence Magazine

- Author: Gil Blank

- Date: Issue 2, 2004

- Format: Print

Interview:

Gil Blank and Eve Fowler

What is it that I wish to convey?…I wish to convey something immaterial and I have to use material means for it. I have to convey something which is inexpressible and I have to use expression. I have to convey, perhaps, something unconscious and I have to use conscious means. I know in advance that I shall not succeed and cannot succeed, and therefore all I can do is to get nearer and nearer in some asymptotic approach; I do my best, but it is an agonizing struggle in which, if I am…any kind of self-conscious thinker, I am engaged for the whole of my life.

– Isaiah Berlin. The Roots of Romanticism, (Princeton University Press, 1999)

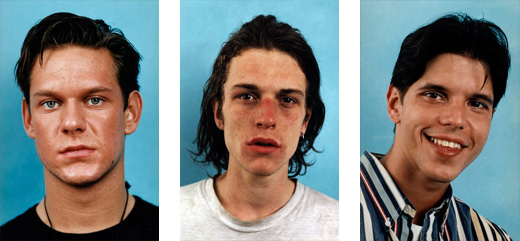

Ten years ago, Eve Fowler made a series of pictures similar in format to what you might expect from any grade school photographer or commercial portrait studio. There was the standard mottled canvas background and the plain, bright studio lighting; she even had the photos printed in frame-ready five-by-sevens and wallet-sized multiples. Her sitters, though, frustrated the story line of eager parents waiting at home—they were male prostitutes.

Photographs ©Eve Fowler

For a recent series, she’s begun to photograph sitters whose most distinctive characteristic is, paradoxically, the ambiguity of their appearance. Neither documentary essay nor personality caricature, Fowler’s work addresses subjects fraught with connotation, but only as stand-ins for more indirect questions. When I discussed individual images with her, names were rarely ever mentioned. In time, I completely lost track of which story was attached to which portrait, a drift towards obscurity that seems not unrelated to Fowler’s project, itself an amalgam of the preferences we maintain of our personal histories.

GIL BLANK Tell me a bit about what led to your consistent engagement with portraiture. Were you at all interested in using it as a way of understanding certain people, or was it much more a consciously controlled act of surveillance, a premeditated artistic and conceptual process, where the subjects, or their sense of identity, were somewhat secondary to your own motivations and questions?

EVE FOWLER When I started photographing hustlers in 1993 I was taking photographs on the street. I wouldn’t say that work was conceptual. But after two years I had the idea that I was attracted to the hustlers because of some things we had in common. The experience was like a return to some feelings I had from when I was growing up. I would say there was something nostalgic about my affinity for the people I was photographing. “Nostalgia” translated directly from its Latin root means “home,” or the pain of returning home, and I decided to try to get that into the pictures. I figured that my nostalgia was for the seventies, because that was the time when whatever made me the way I am was making the hustlers the way they were. I thought making traditional, wallet-sized school portraits would give the viewer a feeling of nostalgia, both good and bad. I didn’t want it to be obvious. I didn’t even say that the people in the photographs were hustlers when I showed them.

You call an affinity for your subjects nostalgic, which I think reveals quite a bit about your perception of both hustlers (as totemic of loss), and the portrait ideal. I assume you didn’t know the individuals before you developed the idea to photograph them as a caste, as hustlers. Yet by an act of conflation—fake school pictures of real dropouts—you imbued them with a specific meaning, with loss, and you say as much by qualifying the work as nostalgic. Is this nostalgia intrinsic to the basic portrait tendency?

I don’t know if I would use the word “caste” because it implies that the work is about class. I didn’t intend that to be a part of the work but I suppose it is. A friend of mine told me the other day she thought all of my work was about survival. A common feeling of loss is an important part of the project. Creating a very controlled catalog was a way to make order out of chaos.

I don’t know why, but I’ve always had a slight aversion to the word “portrait.” I suppose these are portraits, though. When you look at all of them together you can see that there are different types within a type. The type is part of the appeal for the “john.” This body of work functions in different ways for me. On the one hand, it’s a study of something in the world that’s completely outside of myself, and on the other hand I’m making a kind of self-portrait. Vince Aletti wrote that the series was a portrait of the artist as a young man. That made me feel like the work was functioning the way I wanted it to.

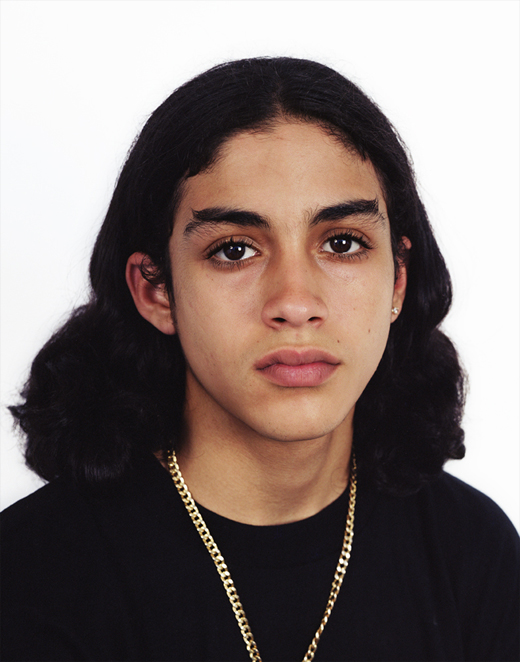

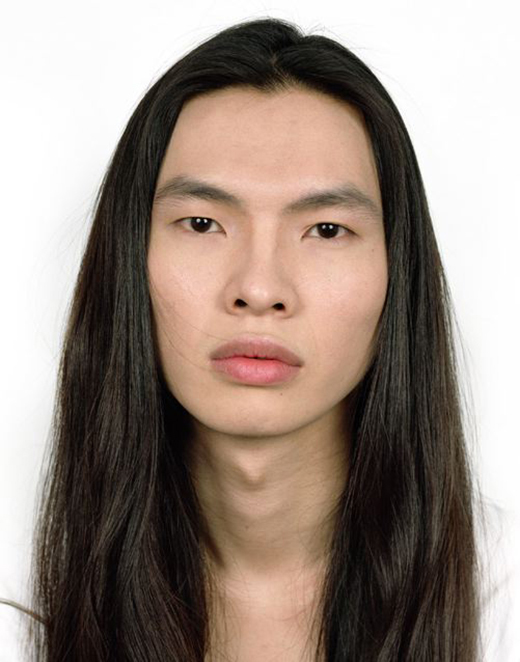

There’s something similar at work in my new series of pictures of people who look androgynous. I’ve never been mistaken for a boy, though I feel like one sometimes. Since I grew up without any women around, I didn’t learn to put on make-up or accessorize. All those things are mysterious to me. Photographing people straight on creates a level playing field, and the viewer is confronted with the subject directly. This forces the viewer to deal with the subject and the subsequent assumptions they might make. The viewer can’t ignore the subject because there’s nothing else at work: no composition, no dramatic light, or any other effect.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

I think that’s another complicating aspect of the work: the studio portrait is an established notion, but traditionally the studio has been a place of complicity, where photographer and model collude to invent a concept of identity. Joan Didion has written that as a young editor at Vogue, she quickly understood by sitting in on Irving Penn’s portrait shoots that there was the photographer and there was the subject—the model in the studio—but there was also the Subject, and that “the two would not necessarily intersect.” This is in direct opposition to the traditions of documentary and reportage, where elements of environment—the street, foreign lands, war—provide a much more palatable perception of vérité. The social issues you bring up are normally the territory of sober documentary, but you seem to be pulling a kind of double-switch: you force a reconsideration of identity by first forcing a reconsideration of the duplicitous mechanics of the portrait genre. Do you follow up on these individual pictures with any others of the same people? Is there any relationship with or further knowledge of them outside of the photographic act? Does your familiarity with them, or lack of it, have any significance in the images?

Before I went to graduate school I was more or less a documentary photographer. I worked for a political advocacy organization for the homeless and I spent about four years documenting people, mostly at night because I worked during the day. Then I went to art school—need I say more? So you could say that I’m using the studio as a cloak. I’m still documenting but I’m doing it in a more effective way. The stripped-down, straightforward portrait allows the viewer to identify more with the subject. I also have a hard time with the environmental portrait because of my history with it. I’m not so interested in an environmental portrait—I want to know something else. This idea of pulling a double-switch is something I thought about a lot. Making the hustler photographs in the studio got ideas into the pictures in a very simple way. The school portrait implies stability, like the way that a caring family might have a picture made. It also helped me create a kind of taxonomy of a type of person. That sounds cold, and it is, but I think it made the work more accessible. August Sander was able to make an incredibly powerful photograph that was simple and straightforward. There’s real depth and intimacy there but it’s never overwrought. It’s warm and cool at the same time. The psychology is warm and the concept (photographing every type in Germany) is cold.

I generally don’t follow up with people but there is one exception. I stay in touch with the people I used to work with before graduate school and occasionally I make photographs of them. I’m struggling to find the right way to portray them.

Your mention of taxonomy and types brings up other questions. Naturally the typology also has a long lineage in photography, and in portraiture in particular. But typologies have normally been a way of marking distinctions in that human catalog you mention, while you seem to be trying to make identity purposely ambiguous. Are the names of these people even important? I imagine the hustlers may or may not have bothered to tell you theirs.

Sometimes I think I shouldn’t talk about this work in terms of taxonomy because it sounds too cold. I was really close to some of the people in that series of photographs. I knew everyone’s name and I spent quite a bit of time hanging around some of those guys—I had them over for dinner, went out to lunch, went to other bars with them, and so on.

So you didn’t just put them into an everyday context in the images; you strove to incorporate them into your actual everyday experience. You’re plainly playing off some ambiguous feeling of alienation in the series—in both series actually—which, with the hustlers, I think most people would attribute to the people, the hustlers themselves, as social outsiders. But you didn’t regard them that way. You brought them into your life; you made them, perhaps counterintuitively, the banal element, having them over for dinner and giving them (fake) school pictures. So what then is the alienating element in the picture? All that seems left is the actual photographic act. You’ve made the traditional portrait, normally an attempt at familiarization, an instigator of dissonance.

I didn’t want to make a traditional portrait. I don’t think you can become more familiar with someone through a photograph, because as I mentioned, a photograph of a person generally has more to do with the person who’s taking it than the person who’s in it. I assumed that I had certain things in common with the people I photographed, but I also assume some of that is projection and not a real part of their own identities.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

What, then, is the common thread between the two series? I mean specifically within you — what was the compulsion to make these two highly particular series consecutively?

I think the common thread has something to do with my identification with the subject. The first person I remember having a real impact on me was a teenage boy who lived down the street. His name was Jimmy Groul. He had long brown hair and he would walk around the neighborhood without a shirt on. He was incredibly sexy—very seventies. I wanted to be like him.

The desire he stimulated in me was very strong, but it wasn’t a crush. My mother always wanted me to wear dresses and cut my hair short, which drove me crazy because I wanted to have long hair and wear pants—I wanted to work the Jimmy Groul look. I think that for about five or six years, I looked like a lot of the guys I take pictures of. My dad just let me be who I was, while it had been just a constant battle with my mother.

The second project started because I kept seeing people on the street that I was drawn to, a sexy young guy that I wanted to be like or that I identified with somehow. The first few subjects were that specific type, but then they got more diverse.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

I think that’s a fundamental aspect of human attraction, be it of a sexual, platonic, professional, or personally identifying nature: it’s always a hybridized complex of desires. I don’t think any single type of interpersonal relationship is based on any single form of attraction, compromised as that admission may make us feel. We often choose our friends not merely for the strength of their character, but because being in their company confirms our self-image in the positive and even sexual way that we might otherwise typically think to seek from a mate. Likewise, we might subconsciously be more sexually attracted to someone who bolsters our professional or personal aspirations. And why not? It seems perfectly logical to desire a mate that we can aspire toward.

That ambiguous area of longing, the intermingling of the desire to simultaneously possess and identify with, seems to me to be the true subject of your portraiture, and I think you’re right to resist its categorization as driven solely by the psychology of either gender or sexual impulse. Because it doesn’t actually matter what the nature of that object of desire is; it is simply there, this quantity of longing, and that seems to be a central part of what drives so much of portraiture. The established photographic impulse is to define, to capture, to know something by means of its isolation: “the decisive moment.” And you’ve flipped that on its head, by obscuring any decisiveness at all in the subject matter of these portraits. Instead, the only element that’s ever pinned down is the nature of our longing, the desire that leads to (but is not ever necessarily fulfilled by) the images we set out to create for and of ourselves.

And you can’t quite believe in that anymore, can you—“the decisive moment.” Besides, I’m not interested in it. You see something in some of these people, and it’s obvious that their sexuality is difficult to pinpoint. It puts them in the margins, depending on who they’re around. That was a relief for me, because I often feel like it’s something that goes on internally for me. I feel alien around certain types of women, particularly the ultra-feminine type. So to see that revealed on the outside, and see how someone can navigate the world in a different way is a relief. I also think I look up to people who are able to deal with the world while having those issues, because it can’t be easy.

Obviously some of the people you photographed aren’t merely androgynous, but transsexual, or perhaps pre-operative.

Yes. There are quite a few women who are pre-operative, and others aren’t even on hormones.

Tell me about a few of these.

That’s Jeremy. I don’t think that he’s taken any hormones, or had any surgery.

But he’s wearing makeup.

Yes, he’s a model; he wears makeup. A friend of mine met him at a party and said, “I thought he was a lesbian with a deep voice.” She said it took her two hours to realize that he was a man.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

Here’s another one I was thinking about. This one seems different from Jeremy, because there doesn’t seem to be the performative aspect—the hair, the makeup.

This is a friend of a friend. It’s someone I knew from around; she was a butch lesbian and about three weeks after this picture was taken had a sex change and is now a guy. But she was on hormones when I took this picture; she was changing and looks a lot different now. She’s very, very attractive. Or he, I guess.

I find it quite interesting that all the images are untitled, which compounds the ambiguity of a project that has such an intense focus on the specifics of identity—ambiguity, paradoxically enough, being one of those specifics.

There are a lot of photographers who make a portrait and then title it with the subject’s name, which seems questionable to me.

I was having a very similar conversation with someone about a Richard Avedon portrait of Isaiah Berlin. This man was a close friend of Berlin’s and he had seen Avedon’s blatantly sensational portrait of him, all high contrast and crooked stare. He took great offense at its blunt title, Isaiah Berlin, philosopher, which, specifically in reference to a photographic document, implied that this single, aberrational and purposely provocative instant was nonetheless a satisfactory encapsulation of the man. I think that’s a distinctly twentieth-century notion, the consummating synthesis of timing, photographic objectivity, and authorial insight, with the title as the cherry topping off the saccharine sundae.

It does seem really naïve. And irritating. People have wanted me to title their pictures, but I’m not tremendously comfortable with that.

And I think that’s one of the big issues at the heart of the photographic pursuit—and, if I can say it, the painterly, literary, and so many other artistic pursuits—at this moment in a hyperspeed, information-glutted culture: How do we approach those fundamental creative challenges by avenues that seem all but closed to us? I don’t know that there necessarily is an answer, but one pragmatic beginning might be to incorporate into the work itself the character of the human struggle to address monumental questions with wholly inadequate means.

Well that’s one reason it’s taken me years to do this project. I started, then stopped when I thought that there was no point to it, and then I started again. I see someone I’m interested in, and this is how I can best render them. I make it as simple and absolutely straightforward as possible, so that the viewer is confronted with nothing other than the subject. If you made pictures of prostitutes on the street, people who don’t want to deal with the idea of a prostitute would be able to find any other visual element in the picture—the grass, the fence, whatever—to avoid the subject. You can’t really avoid the subject here. And that takes the art out of it too; it removes the athleticism and that old-fashioned concern for making a picture with composition and so on.

Thomas Ruff does that of course, and to my mind most wholly exploits that formalist aspect of an evacuated approach to the portrait genre, but I don’t sense that so thoroughly in your work. You’ve acknowledged the impasse that he suggests, but there’s one key difference, and I think it relies upon content. This is where you separate yourself from Ruff and Julian Opie, because your subjects do matter a tremendous deal—for all their ambiguity, both your images and their subjects are so entirely wrapped up in specificity. That specificity of identity may be in flux at the moment of the image formation, but it’s a desired state, conceivable though perhaps inaccessible. The pictures are a crystallization of longing—whether your subjects’ or your own—and that immediately places your work in a territory distinct from the other portraitists. Neither male nor female, the interstitial character of your subjects is the perfect metaphor for your own portrait practice, caught in a suspension of indeterminacy.

I don’t think the idea of depth—personal, emotional resonance—is always important in art. I do think though that it’s more common for photographers to think that they’re making something that has more of that emotional resonance.

Sure. Press the button and you get instantaneous meaning. Isaiah Berlin, philosopher.

Right, and so it ends up feeling phony. I think I’m trying to get at that resonance in a more roundabout way. I want it to be there, and I think it is, but I don’t want it to be so obvious.

Tell me the story behind this one.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

He’s a pre-operative. He says he’s a lesbian. It gets pretty complicated: when you’re biologically a man and you say you’re a lesbian, it’s a little hard to get women to be okay with that, since most lesbians want to be with other women. It’s a tough spot. Similarly, I met a group of young women who like to be called “boys.” They consider themselves transgender whether they’re on hormones, have had surgery, or not. The word has more to do with a state of mind than an exact physical state. I know a lot of older butch dykes that don’t mind being called women, but the younger set who consider themselves transgender, whether they’re transitioning or not, like being called boys.

Not men?

No, because they’re more like waify boys.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

And this one could be your Jimmy Groul. Or Rosebud.

Yeah! Exactly. That’s pretty much what he looked like, though he was maybe a little more muscular and attractive.

I’m sure he was.

This one was a bartender at Trannyfest, a fundraiser for a film festival, and everyone had a crush on him. Every gay guy and every gay girl. Really cute. He’s pretty sexy. And this one is a woman transitioning.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

Really? Looks like she’s already there.

I don’t know what state he’s in here, but I imagine he’s on some kind of hormone because of the facial hair.

This isn’t Phranc, is it?

No, but did you know that Phranc sells Tupperware in Los Angeles?

What’s that all about? A sudden yearning for Midwestern domesticity?

I think it’s a yearning for money.

This is another lesbian that’s a biological male. She calls herself Valerie. I think she’s beautiful.

Photograph ©Eve Fowler

Well the two of you have definitely collaborated here to give him that Botticelli air—or at least hair—and all that image suggests: birth (or in this case, rebirth), an idealized beauty, and of course the arrival of love.

I’ve got a picture of her in a dress that makes her look like a teenage girl.

You mention that, his ability to adopt the look of a teenage girl, and the lesbians’ desire to be referred to not as women, or even as men, but as “boys,” and the self-conscious impossibility of those desires, of becoming not merely another gender but of actually regressing to another age, amplifies the theme of longing. There’s a deliberate yearning for something that is not only in opposition to your fundamental state, but that is in fact totally inaccessible.

There is an element of that longing, and it’s a big part of my connection to this. I definitely agree with what you’re saying about regression in terms of myself—it’s in a lot of my work. It’s complicated. There might be a longing to return to the past and fix it.