- Source: Kojo London

- Author: Kojo Abudu

- Date: April 2, 2019

- Format: Digital

Eric N. Mack:

Painting in an Expanded Field

Lemme walk across the room is the title of Eric N. Mack’s latest exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, an immersive site-responsive installation that successfully engages with, and simultaneously problematises, the categorical boundaries separating painting from sculpture, performance, architecture and fashion. Within the museum’s airy Great Hall, the 32-year-old artist’s visual language, expressed most captivatingly through his textile-based works, materialises an aesthetic rupture. The self-declared painter composes abstract ‘paintings’ that are themselves abstractions of painting. Indeed, Mack’s ‘paintings’ are not simply the application of oil, dye or acrylic to canvas, paper or linen; his paintings extend into space, converse with the architecture, move with the flow of air, prompt the viewer to walk by and around them, and allow the viewer to look through them. Tactile and colourful but also bodily and spatial, Mack takes the formal and experiential axioms of painting and pushes them in a different direction. He paints, sure, but as the artist says time and time again, he does so in an “expanded field”.[1]

In her seminal essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, published in 1979, art historian and theorist, Rosalind Krauss, attempted to make sense of the novel sculptural languages that had emerged during the 1960s and 1970s[2]. Krauss argued that these newer works, which were swiftly historicised as “sculpture” by critics, actually shared very little, structurally and symbolically, with what had preceded them, namely, modernist sculpture and commemorative monuments. Sculpture, which had hitherto been defined in a double negative bind as not-landscape and not-architecture, could not accommodate the expansive terms of discourse set by the works of Richard Serra, Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson, Christo and Bruce Nauman, for example. Krauss showed that the aforementioned artists weakened the modernist categorisation of sculpture, moving it beyond its double negated condition into an expanded field where other sculptural languages could be validly articulated. In this expanded ‘postmodern’ arena, “practice is not defined in relation to a given medium … but rather in relation to the logical operations on a set of cultural terms, for which any medium … might be used.”[3] I want to argue that Mack primarily engages with the logical operations of painting such as materiality, colour and surface, but uses these formal coordinates as a starting point for negotiating the aesthetic languages of sculpture, architecture, fashion and performance. Viewed in this manner, the artist could be said to “occupy and explore” an expanded field of painting, which in contrast to Krauss’s formulation, likely exceeds four designated possibilities[4].

Installation View of Lemme Walk Across The Room: Seat Pleasant, 2019. Jonathan Dorado / Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum

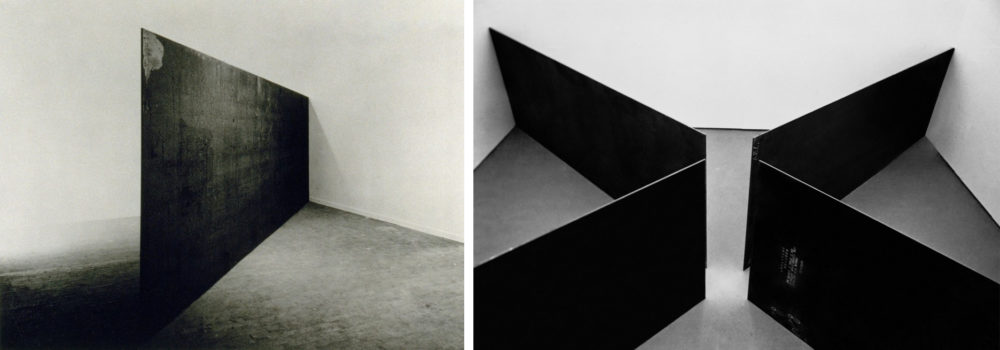

As viewers approach the site of Mack’s installation, the first piece they likely encounter (or are drawn to) is Seat Pleasant (2019), a dye-textile work that coheres the site’s visual field and asserts its presence from any of the hall’s four corner entrances. Mack assembled the work by pinning large sheets of fabulously dyed cotton to two perpendicularly hung, intersecting ropes that span across the entire space. As the exhibition title suggests, the viewer is encouraged, tempted even, to walk beside the hung textiles, guided around the room by the shifting vectors of the suspended ropes. As the viewer walks-across-the-room, in between and around these textiles, she becomes increasingly aware of the positioning of her body, and the directionality of her movement, in relation to time and space. Perceptual qualities of physical space, such as distance, are thoroughly engaged, as the textiles articulate the spatial intervals that connect the Great Hall’s corners; the work “forces a perspectival reading of the space” as Serra would say[5]. Seat Pleasant thus intervenes in the museum’s classical architecture by cutting up the site’s space and altering how bodies experience and move through that space. The work’s emphatic phenomenological delivery as well as its partial embodiment of what Krauss would call an “axiomatic structure” (between architecture and not-architecture) recalls the early works of Richard Serra, in particular Strike (1969-71) and Circuit (1972)[6]. Remarking on these early works, Serra states “[Circuit] opened up the possibility of entering into a space and making the space the sculpture, so that when you enter the room, you become a part of the work … [Strike] opens the space and fans out into the field as you walk it. It declares the entire room as its content”(italics mine)[7].

Left: Richard Serra, Strike, 1969-71; Right: Richard Serra, Circuit, 1972

However, unlike Serra’s use of industrial steel plates, Mack’s work plays on the light materiality of cotton. Echoing the vibrantly coloured, hung canvases of Sam Gilliam, Mack takes the canvas off the stretcher and extends it into space, thus merging the sculptural and the architectural with the painterly. The artist’s hand-dye technique, which gives rise to elongated, flat patches of orange, green, pink and blue bears a formal resemblance to the style of abstraction popularised by the Colour Field painters, many of whom, like Gilliam, came from Washington D.C., where Mack was born and raised. The bright, playful and grid-like blotches of colour laid on the fabrics create a variegated visual filter for viewers that look through the fabric and also bring to mind check patterns that one often associates with quilts or clothing, such as gingham or plaid. This not-so-subtle symbolic allusion to fashion and homely craft ties back to Mack’s fundamental concern with the relationship between the work and the viewer’s body. In other words, not only is the viewer sensitised to his or her bodily spatio-temporal orientation; the viewer also engages with the work as intimate, affective material – as fabric that can wrap around and give warmth to his or her body. For me, Mack’s immersive work triggered sensations I felt as a child being confronted with the voluminous presence of my parents’ king-size bed sheets drying on the washing line in our Lagos backyard; the short-sleeve Cuban collar shirts, dyed with bright splashes of red, yellow and green, which also hang on the suspended ropes alongside the large textiles, further punctuate the work’s probing of the private and public symbols that one often places on seemingly quotidian pieces of clothing and fabric.

Sam Gilliam, Carousel, 1979. Courtesy of Walker Art Center

Mack’s frequent collaborations with British artist/designer, Grace Wales Bonner, have clearly influenced his approach to textiles, specifically his interest in how clothes move and communicate an identity[8]. Also in Seat Pleasant, the artist mounts a slowly oscillating fan on the wall by one of the entrances, which blows gently on the hung fabric. The fabric ripples with the movement of air, and thus, at each moment, embodies a different spatial configuration. By instantiating an ever-shifting mode of presence in relation to the viewer, by emphasising the here and now – “the indexical present” in Adrian Piper’s words – the work itself engages in a performance, moving as though a body were wearing it down the runway or across the street[9]. Even in areas of the site where the breeze of the fan is not felt, the very motion of the viewer’s body activates the work by producing a similar rush of air. This relation between viewer and artwork, which is reciprocal and dynamic, shifts painting – a conventionally static medium – into an exciting performative mode.

Wales Bonner, Mumbo Jumbo, AW 2019. In the background is Eric N. Mack’s Capital Heights (via stretch), 2019

Installation View of Lemme Walk Across The Room: Tessuti Raponi (Cia Milano), 2018. Jonathan Dorado/ Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum

Other works in the installation such as Tessuti Raponi (Cia Milano) (2018) showcase Mack’s ability to paint with fabric, as he meticulously juxtaposes the colours, patterns and textures of various garments to generate a collagic image/material that floats in space, hovering over the viewer’s body. The textiles in the composition are readymade fabrics that Mack often comes across on his frequent shopping sprees – the title directly references a well-known fabric store in Milan, one of the world’s fashion capitals. The artist’s demonstrated affinity for assemblage besides showcasing his formal deftness at composition, also channels a [black] radical impetus. According to curator and art historian, Adrienne Edwards, “the concept of assemblage … is the basic set of conditions to enable a becoming. It is a mode of agency that works by constituting a multiplicity of response to the apparatuses delimiting a subject’s pursuit of his or her most fundamentally motivating desires”[10]. As an irruptive strategy of perpetual ordering and reordering, a conscious refusal of the singular, the original, and the ‘logical’, an effective/affective means of making do, assemblage wields a generative [black] radical force that relentlessly critiques the normative bases of modernity, from the African-American vernacular tradition of quilt-making to the emergence of the Dada movement to the contemporary work of Robert Rauschenberg and David Hammons to the sophisticated use of sampling and remixing in hip-hop culture. This historically transmissive radical force presents itself in Mack’s ouevre as an aesthetic rupture.

Installation View of Lemme Walk Across The Room: Tartan Film Strip from 1987 till Recent, 2019. Jonathan Dorado / Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum

Mack’s nod to fashion reappears in a large, more conventional collage attached to one of the halls’ white walls. Titled Tartan Film Strip from 1987 till Recent (2019), the work is composed of disparately sourced magazine clippings and photographs affixed unto two large, semi-conjoined pieces of oil cloth. The artist (re)employs a kind of Rauschenbergian poetics, as he extracts images and texts from mass cultural sources – newspaper excerpts, photographic advertisements, fashion editorials, magazine covers – and places them unto a singular image plane, constructing a recontextualized narrative that is deeply personal, anecdotal and elliptical[11]. Moments of discordance such as the placement of a Fader cover of Kelis above an African newspaper clipping celebrating the electoral victory of Nigerian president, Muhammadu Buhari, alludes, on one hand, to collage aesthetic of the fashion ‘moodboard’, and on the other hand, to the non-linear and internally incohesive functioning of human consciousness, memory and subjectivity.

In Lemme walk across the room, Mack enacts irruptive formal interrogations with a playful and personalised approach; a light-hearted sensibility that derives in so small part from the artist’s unapologetic flirtations with the cultural codes of fashion and hip-hop culture[12]. His installation left me with more questions than answers, the main one being, “What exactly is painting?” I believe Krauss’s notion of the expanded field proves useful here because it allows critics and historians to acknowledge the aesthetic radicality inherent to Mack’s work while also using current (albeit limited) discursive tools to talk about that radicality. In other words, I accept Mack’s works to be paintings, as they primarily engage with its logical operations (surface, colour, materiality) but simultaneously, I am aware of his works’ critical distance to some of painting’s historic conventions (flatness, stillness, use of paint) hence the need for an ‘expanded field’. Like Serra and Christo, Mack’s ‘paintings’ critique the modernist dogma of aesthetic autonomy and its espousal of a Kantian disposition toward disinterested viewing. Instead, Mack centralises the experience of the viewer by enveloping him or her, physically and psychically, within the mesmerising patterns and vivid dyes of his performative, spatial textile constructions. The assertive architectonic character and large scale of both Seat Pleasant and the short-lived Halter (2019), commissioned for Desert X, provide exciting clues as to where the artist’s experimental practice seems to be heading. Only time will tell if Mack’s transdisciplinary, category-defying tendencies will continuously expand the boundaries of painting or eventually break them, bringing further attention to the medium’s protracted identity crisis.

[1] Eric N. Mack in conversation with Tim Marlow, Artistic Director of the Royal Academy of Arts, at Simon Lee Gallery, London, 12 April, 2018.

[2] Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, in Hal Foster’s The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, 1983

[3] Ibid. p. 41

[4] Ibid.

[5] Richard Serra quoted in Richard Serra and Hal Foster: Conversations about Sculpture, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2018, p. 142

[6] According to Krauss, an axiomatic structure is involved in “mapping the axiomatic features of the architectural experience – the abstract conditions of openness and closure – onto the reality of a given space” p. 41.

[7] Richard Serra quoted in Richard Serra and Hal Foster: Conversations about Sculpture, p. 98-99.

[8] Mack’s work, A Lesson In Perspective (2017), was included in Bonner’s recent exhibition, “A Time for New Dreams,” held at the Serpentine Galleries in London.

[9] Adrian Piper quoted in Jörg Heisser, “Adventures in Reasonland” in Adrian Piper: A Reader, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018.

[10] Adrienne Edwards, “The Struggle for Happiness, or What is American about Black Dada” in Adam Pendleton’s Black Dada Reader, Koenig Books, London, 2017, p. 29.

[11] Mack was an artist in residence at the Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva, Florida in 2017.

[12] The references to hip-hop culture were made more explicit at his 2018 solo exhibition at Simon Lee Gallery in London titled “Misa Hylton-Brim”, after the influential 90s hip-hop stylist.

The concepts in this review were expanded upon in a long-form essay, “Eric N. Mack: Materialising Aesthetic Ruptures,” included in the catalogue for the Unbound exhibition at the Zuckerman Museum of Art, curated by Nzinga Simone, March 2020. For more writing by Kojo Abudu please visit the kojolondon.com website.