- Source: Hyperallergic

- Author: Dan Nadel

- Date: January 04, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Brian Belott’s Time Pieces

Belott’s “frozen artworks” signify duration in the interval between the water freezing and the ice melting.

For many years Brian Belott painted cats with clock faces for eyes on glass. These are not on view here, but they are worth imagining, and are illustrative of Belott’s truest subject matter: time. Nearly everything in his current exhibition at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise is related to the artist’s profound interest in exhuming and archiving the discarded and the dispossessed — from the work of forgotten painters and obscure jazz musicians to children’s art to obsolete electronics to his own art — not as an act of nostalgia, but rather as a way to seek new ground and then open up it up for collective examination. Belott rewinds time — recalling Asger Jorn or Claes Oldenburg’s Brut reversions in philosophy and aesthetics — in order to find a place that felt muddy enough that there was no tradition binding his consciousness. A sloppy ground from which to move forward.

Time is intrinsic to Belott’s and my own experience of this exhibition, which doubles as a mini-retrospective. His “frozen artworks” — materials embedded in ice and stored in industrial freezers in the gallery — signify duration in the time it takes for the water to freeze and the ice to melt, should a circuit blow, a freezer darken, and his frozen paintings be exposed to the atmosphere. (A freezer did in fact blow out a few months back, setting one of his studio rooms ablaze, destroying new and old artworks alike, and necessitating the form of his current exhibition.) Time is present in the 20-year-old paintings on canvas board that foreshadowed and influenced post-2005 New York expressive painterly moves. And time is present in his caveman riffs on modern technologies: calculators and remote controls are coated in sand and stones. There is such poignancy in these futile devices, mounted stupidly on thin wood stands throughout the gallery, daring me to trip and break them — or maybe break off the stand and use it as a selfie-stick.

I’m extending a lot of pathos to an artist who, more often than not, defuses such sentiment via vaudeville-meets-Cabaret Voltaire-meets-Jerry Lewis performances — a symphony of electric can openers, for example — and an ongoing obsession with children’s art that has consumed his energies over the last few years (and was the subject of his previous exhibition at the gallery). The trick is to see past the performances, which encompass artwork titles, display systems, and the entire infrastructure of art, and really take in what the objects embody. So, back to the freezer.

Brian Belott, “Untitled” (2018), top: plastic hand, hair gel, Aquafresh, twine; middle: hair gel, snowy garland, hand massager, Halloween mask, hassle; bottom: clay, mustard, sand, cotton, paint, each in ice suspended in freezer with hardware, 79 x 27 x 32 inches

Each of three glass-fronted freezers in one room of the gallery contains rectangular blocks of ice mounted on a vertical rod suspended. Encased in the ice are layers of material. They remind me of three-dimensional versions of Man Ray’s “rayographs.” They also represent Belott’s decades-long project of creating works that are transparent in form and idea — allowing viewers to see the work and how it’s made in a single look. This approach, ranges from paintings on glass to laminated works. In one “frozen” painting a plastic hand, surrounded by a looping, ethereal string, emerges from the hazy crystal grasping for space. In another, tabs of pale minerals subtly radiate from the center. Still another frames brass doorknobs, an abacus, and a grandfather clock eight between lengths of green- and blue-tinted ice. Belott, keenly aware of the slight tradition of frozen painting and sculpture (and a related category in which he participates — food sculpture and drawing — dominated by Dieter Roth and Fischli/Weiss) focuses on creating delicate and ethereal beauty that contrasts with the industrial container housing the works. Fragile or sturdy, vulnerable or aggressive, the ice paintings sometimes seem more found than made, an effect highlighted by the black-out room in which they’re displayed like centerpieces in a gem museum. The experience of encountering these glowing vessels in the dark is that rarest combination of sublime, funny, and moving. There’s nothing else quite like it and it is worth seeking out if only to sooth or enlighten your addled mind.

Brian Belott, “Untitled (Fan Puff)” (2016), mixed media, 83 x 73 x 8 1/2 inches

Next to the freezer is a whirling fan in a window cut into the wall; it’s part of “Untitled (Fan Puff)” (2016), related to Belott’s series of “puff piece” works. Begun in the late 1990s with cotton balls, the current version uses cotton batting as either a support or subject. In the latter case, painted bulges of batting in various hues compose a tondo, which might house a detourned calculator or remote control or some other modern debris. In the former, the batting is shellacked between hunks of festooned paper and sometimes activated with an inset fan or, in the alarming case of “Untitled (Puff)” (2018), a motion sensitive hair dryer that blows hot air as the viewer approaches. Now there’s a joke that is all about the timing. The hair dryer also briefly distracts from the burnt black char (a result of the artist’s studio fire) that coats a quarter of the piece and eats away at a corner. For someone so funny, Belott doesn’t traffic in irony or jokes-on-you condescension. The comedy comes from experiencing the totality of the artwork.

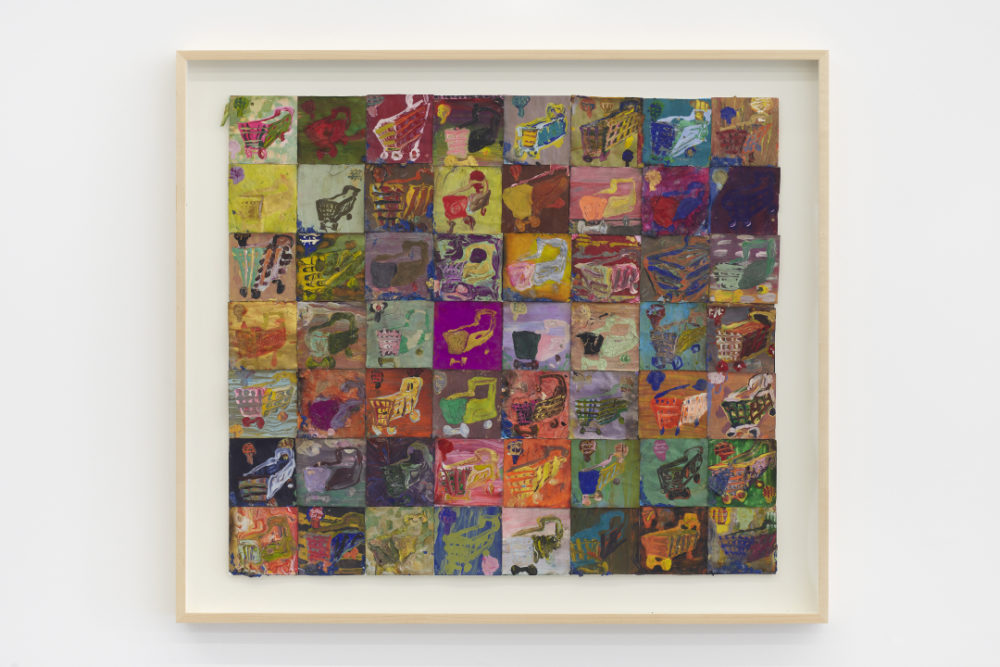

Brian Belott, “Shopping for Color” (1996–1998), tempera on Post-it notes, 28 1/4 x 31 3/4 inches

Chance moments, funny decisions. Wandering through the years and the scorch marks, the exhibition is as much about moments of discovery as it is about the art objects. Eight untitled drawings made with skeins of mustard look better with singed edges than as originally exhibited in 2014. Raw food drawings are cooked, fire adding some tone to them, and what is old is made new again. It’s brutal ground to discover ideas within, but such is Belott’s mode in the world — which isn’t to deny him rigorous agency in the making of the things: even after a blaze his efforts are deliberate. It’s a rare mind and hand that can transform a personal and professional disaster into generous and beautiful art. Perhaps no work is more generous — and generative — than Belott’s meditation on the shopping cart, Shopping for Color (1996–1998). It is ugly analog tech serialized: post-it notes are painted different colors and arranged in a grid; each expert gesture appears, but certainly is not, casual. This deceptively simple object, appropriately tucked away from the main exhibition space, takes us back to the beginning of Belott’s activites and points the way forward. At once a biographical key, a container of consciousness, and a blurt of color, it’s about as beautiful a collection of paper you’re likely to see in New York.