- Source: The Washington Post

- Author: Sebastian Smee

- Date: October 12, 2018

- Format: DIGITAL

Art’s sharpest social commentators since Andy Warhol reveal the state we’re all in

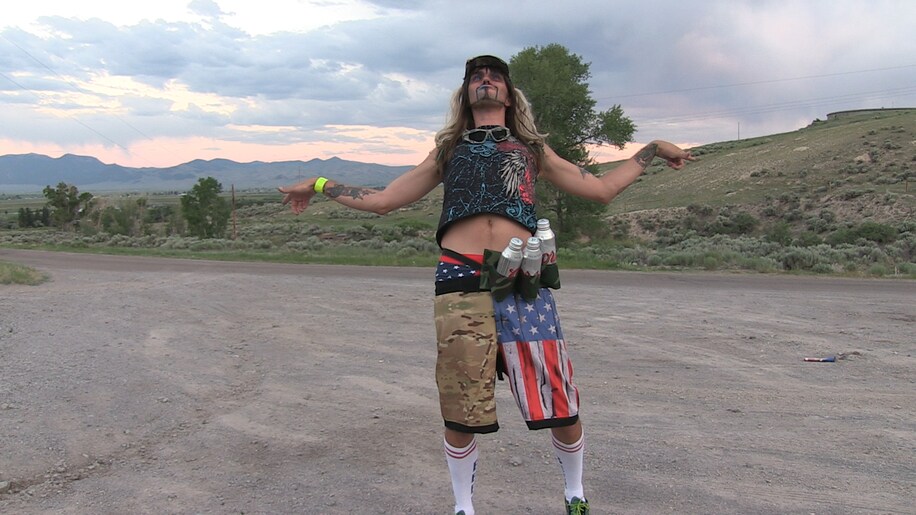

A scene from "Mark Trade." (Ryan Trecartin/Regen Projects/Spruth Magers)

BALTIMORE — It’s hard to describe the sharp, metallic-tasting genius of Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin other than to say they have skewered the zeitgeist. No artists, in fact, since Andy Warhol have reflected American culture back on itself with such a combination of hyper-vigilance and underlying hilarity.

You may not instantly love their work, which takes the form of videos, often presented in room-scaled installations. They’re frenetic, loud, disorienting and long. In no way do they announce themselves as “masterly.” But their films, most of which are freely available online, are more artful than they look.

The Baltimore Museum of Art is hosting an exhibition of three of Fitch and Trecartin’s films, each screened inside a different installation. Of the three, the most riveting is “Mark Trade.” You watch it from a stool in a dark room set up like a sterile hotel bar with electric fans, velour rope, carpet and an ambient, drone-like sound emitting from speakers.

Mark Trade, the film’s main character, is a classic Fitch/Trecartin creation: Preposterously dressed in shorts and long socks, he has a dark goatee, colored eye lenses and blond pigtails protruding through his Lone Wolf cap. He is vain, incoherent, vapid and lascivious, yet weirdly magnetic and quick-witted.

All of Trecartin and Fitch’s characters feel slightly unreal. They’re played by real people (including Fitch and Trecartin), but they seem to embody the avatars and clones of Internet culture, the “selves” who appear on reality TV or unspool across social media or YouTube comment threads spewing venom, humor and random assertion. Their hair styles, outfits and makeup are egregiously crass, their voices often sped up to helium pitch or dripping in phony accents.

Mark Trade has slightly more substance than their other characters. He has to carry a whole film, after all. We surmise quickly that he has paid a film crew to shoot him for a documentary about himself. “I like it when he acts like we hired him,” says one of the crew. (They wear tank tops emblazoned with “WITNESS.”) Trade is unfazed: “I’m on camera, I couldn’t be happier about the entire thing.”

We see him hamming it up for the cameras in and around National Park tourist sites, in an RV, and at a small lakeside home in Oregon. Intermittently, there is friction between him and the crew. This tension (tantrums from Trade, eyerolls and pouting from the crew) becomes part of the show’s rhythm.

Trade has his own, post-human reality. He has no core, no self-awareness, no inner life. All he wants to do is perform before the camera. “I’m pretty sure as long as I’m in front of the camera, beauty ain’t nothin’ to worry about,” he croons, sweatily.

He does karate kicks, makes lewd gestures, plays air guitar. From his mouth stream hilarious, emphatic statements, doggy howls, jokes, complaints. “The contract I signed said there’d be a spotlight,” he barks. But there’s no more weight or feeling for consequence behind this assertion than anything else Trade says. The only constant about his mind is its total discontinuity.

Trade’s crass and absurd presence is set against the natural vistas all around. This creates a sort of cognitive dissonance, compounded by the viewer’s awareness of watching “Mark Trade” inside an art museum, part of which has been made over into a hotel bar.

“The human era went like that, like a sweatshirt on a campfire,” says Trade. It’s one of a number of statements that set the film in a putative future, when there’s talk of old realities — animals, humans, nature — being “reanimated.” In front of some bison, Trade says, “There’s a chance they’ll animate them again, but that’s to do with paying attention back then.”

Many of the lines are funny: “We’re really off the griddle.” Or: “Someone invented this handwriting once and eventually it became at the center of this novel I’m in.” Others are pointedly absurd: “Night vision only works on the north side of trees.” Or: “You might have a couple of people willing to die for a salad, but most likely that was eons before the salad era.”

Trecartin and Fitch were both born in 1981 and met as students at the Rhode Island School of Design in 2000. They have been friends and collaborators since then, although before 2011, Trecartin was known mostly as a solo artist.

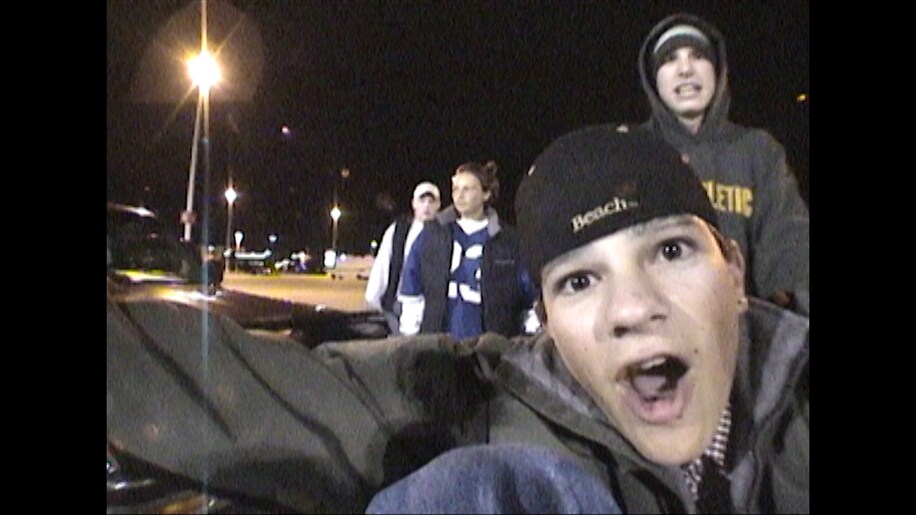

When Trecartin was 17, his mother gave him a Sony Handycam. Inspired by the “Blair Witch Project,” he used a night-vision lens to film a week-long ritualized “war” between the juniors and seniors at his high school. He edited it into a movie, “Junior War,” 14 years later.

A scene from "Junior War.” (Ryan Trecartin/Regen Projects/Spruth Magers)

“Junior War” is the second of the trio of films at BMA. The ritual involved vandalism, binge-drinking, partying and run-ins with the police. We see high-schoolers smashing in mailboxes with baseball bats. The footage is blurry and filled with menace. Abrupt, emphatic things are said, in a manner evincing more concern for the judgment of the camera than for how the statements relate to reality or to any preceding statements.

This — the emphatic non sequitur — has become a kind of structural principle underlying all of Trecartin and Fitch’s videos. With their kinetic editing, complex layering and split screens, the films are, among other things, an ongoing joke at the expense of the very idea of “continuity.” Artistically, this puts them in an avant-garde tradition that begins, perhaps, with cubism, develops into the disruptive collage aesthetic of Kurt Schwitters and Robert Rauschenberg, and merges with an interest in gender blurring, playacting and psychosexual pressure derived from Marcel Duchamp, Claude Cahun and Cindy Sherman.

The third film, “Permission Streak,” screened in a room set up as a hybrid of a diving pool and a gymnasium (the installation is called “Trigger Rink”), takes discontinuity to a new extreme. Glamorous young (mostly) women with futuristic or off-kilter makeup compete to be accepted into a group dynamic that might just as easily spit them out. “I can’t handle my body,” says one. “When I chop down a forest, it makes a really loud sound, even when no one’s there,” asserts another. “Facts do turn into opinions and they smell funny,” says a third. The film then breaks down into a kinetic sequence of inside stunts involving wind-machines, spotlights, camouflage outfits and fake palm trees.

A scene from "Permission Streak." (Ryan Trecartin/Regen Projects/Spruth Magers)

What are these films telling us?

Watching them is like being at a party where everyone is trying to be heard at once. Which is to say, it’s like being on Instagram or Twitter. It may be misleading to say they’re “about” social media or reality television or the heavily mediated, dematerialized world we choose to spend our days in. But they are about how all of us relate to the world in this new era: how we conceive of ourselves, how we communicate.

The jagged, incoherent feeling Trecartin and Fitch create emerges from the sense — intensely familiar to teenagers but perhaps also, increasingly, to politicians, preachers, journalists and teachers — that no one is listening. In fact, these films propose that no one need listen. We are in era of solipsism, where listening is beside the point and a distraction from the main game: gathering followers, likes and comments.

Personality itself in this brave new world has become slippery, diffuse and biddable. Online, in front of the cameras, and in daily interactions, people are actively choosing to be limited versions of themselves — to be stereotypes and caricatures — to get the attention they crave, the results they want. Fitch and Trecartin convey all of this.

Their films induce a rising panic. The more you look, the less euphoric, self-made and free their characters seem and the more they appear to be subject to various kinds of control: the control exerted by peer pressure, certainly, but also by deeper, more structural and sinister forms of power.

The characters’ sloppy makeup suggests forms of camp, but also a kind of haste, forced on them by a capricious, unknown authority. Their behavior has both a pathos and a manic intensity. All of which turns the films’ surface hilarity into something stressful, arbitrary and relentless. Like what?

Like civic life in America.