- Source: GARAGE

- Author: ELIZA WALLACE

- Date: SEPTEMBER 06, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Word Play and Women’s Work with Eve Fowler

The artist's universe unrolls in two consecutive shows at Morán Morán in Los Angeles.

Courtesy of Morán Morán

Eve Fowler is writing her own stuff now. But other peoples’ words keep crowding her head. In her new exhibition These Sounds Fall into My Mind, (from The Bucketheads 1995 house song, The Bomb!) she invites these other words to live alongside her own. Known for her recontextualizing of Gertrude Stein’s written works, Fowler has been experimenting with experimental text for over a decade. Stein’s words are still a part of the warp and weft of work in her current show, but her writing process has become her recent fascination.

“Writing is hard, but it makes me happy,” Fowler said to me, over coffee and an LA August’s midmorning sweat sticking me to the leather booth. I write “fascination,” but maybe it’s more like: “Itch to scratch.” “Medium-sized demon to exorcise.” “Loose tooth to worry.” “Soap bubble to hold.” Encouraged to write a book by a friend, Fowler started on New Year’s Day in 2018. As she began to write, phrases from other artists and writers collided and merged with her own. She would hear “pearls that were his eyes” from T.S. Eliot’s Wasteland, and it would drop, like pearls on eyes, right into the middle of her sentences. Fowler apprehends the phrase from Eliot who took the phrase from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and suddenly the words fold into a meditation on who really owns words anyways, man. The words are always someone else’s, your own, nobody’s.

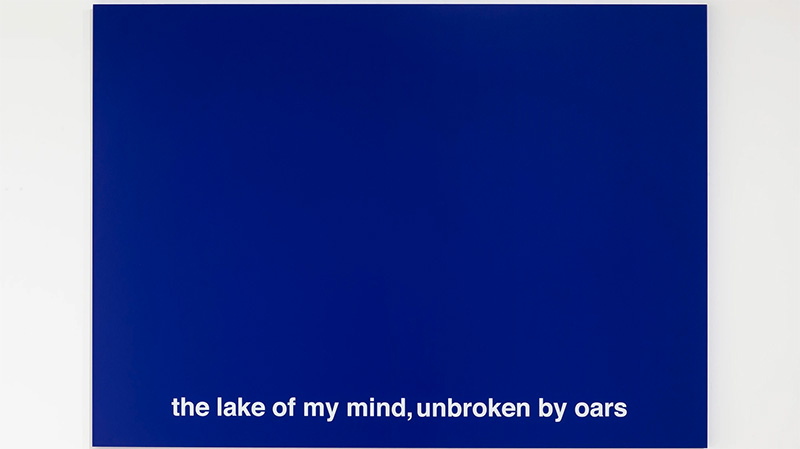

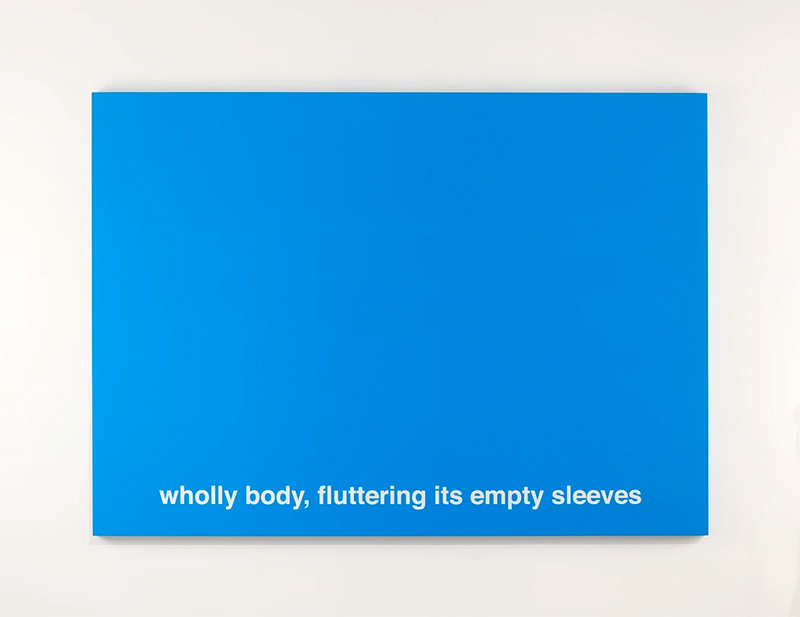

These Sounds, opening September 7th at Morán Morán Gallery, includes a film, a video, and six wall pieces. Fowler’s writing plays itself out in the video and the wall pieces. Across blue fields, like a sky, an ocean, or the blank blue TV screen before the VHS player engages, appear the phrases of a poem. The fields of varying shades of blue and the phrases drop steadily, like pebbles into water, like sounds into a mind.

Eve Fowler, These Sounds Fall Into My Mind (installation view) (2019). Image courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán.

Six painted works of pristine, sincere, blue aluminum panels with more of her text running along the bottom will hang alongside the blue video. Known for making Colby posters out of text from Stein’s Tender Buttons, which coded the writer’s word play in the forum and material of the LA street, Fowler once again uses a medium that respects her home and work site––blue auto paint. In Los Angeles, there are countless more auto body shops than there are official art supply stores. This degrades the paint not a whit, only strengthens its constructive tenor.

Fowler’s panels recalled to me a very affecting part of Infinite Jest, where a character describes posters at his AA meetings: “The Provident cafeteria walls…are tonight bedecked with portable felt banners emblazoned with AA slogans in Cub-Scoutish blue and gold. The slogans on them appear way too insipid even to mention what they are. E.g. ‘ONE DAY AT A TIME,’ for one.” Fowler’s text is not insipid, but the panels have a similar effect to these slogans that hold a kind of time-release power. “Easy Does It!” and “Turn It Over!” and “One Day At a Time!” mean nothing at first, but with enough rolling them around on the brain, they hold a certain power. There are phrases that become a part of us, drop into our mind, and take on new life.The final element of Fowler’s solo show is the second part of her film series, With It Which It As It If It Is To Be. The films join women and women identifying artists in their studios, quietly observing them at work in black and white 16mm. The Gertrude Stein text Many Many Women is voiced over by different people, the images of the artists in their studios, close ups of their hands sanding or painting or scraping material into form.

Her first film entered the studios of friends and close collaborators. It opens on a woman’s back, like Godard opens on Anna Karina’s back in Vivre Sa Vie (1962). Sontag described the scene’s blocking as a deprivation. He is keeping the viewer from getting too involved. Fowler’s choices in where she points the lens and what she allows us to hear, also make for a restrained relationship. But her intent is different. She aims to dematerialize the art object, in this case, to remove women from the position of art object. She films with utmost respect––action, decision, beauty happens only at their hands, their lead.

"With it which it as if it is meant to be," Part II, 2019 (still image), Courtesy of the artist

She invests in their movements, relinquishes manipulation over anything except for the work itself. Fowler layers Stein’s repetitive, experimental play of text over her subjects as they engage in their daily job of playing with their respective mediums. The whole strata of her pieces consists of process and play. Perhaps work is not the only window to the woman’s identity, but Fowler has cut glass for a window both conceptual and substantial. The logical buckling here is distinctly frustrating and female, but most importantly, poetic.

The actual experience of this woman’s work doesn’t fit with my overdramatic subconscious howling Kate Bush lyrics. Fowler’s approach feels compassionate, straightforward, relaxed, considered, but not overly academic, arch, telescopic, or sentimental. To watch her first film is to be draped in the warmth of friendship and safety. Of the first film, Fowler says, “These are the people who are important to me…I wanted people to see them.” Witnessing a friend create something instills a sense of privilege, pride, and gratefulness. I love my friends so deeply that sometimes my throat catches when I see them in their element. This first chapter was a love letter, a thank you to her friends and collaborators, that a viewer can’t help but recognize.

In the first part, when she entered their workspace, she recalls her friends being glad she was there, finding her presence stimulating. The second film follows this same conceit of reverently documenting women at work in their studios, but with a new series of artists, all of them older women and women identifying artists, decades deep into their careers and practices. Entering the studios of the artists of Part II was a different experience. These women enter their studios with purpose and grace, their practice assured and established. Fowler had to build trust with them throughout the filming process to gain the kind of closeness the first film provided.

Many artists move through the world with hubris, claiming not to reference anyone else in their field. Who is above peer review? Who is above citation? Fowler’s has the rare sensibility to equalize her own words and work with the words and work of others. With humility, she holds close her contemporaries, predecessors, her friends, and her personal life. We’re all on the same team, it seems, or at least, should pay attention to each other as we head toward the same drowned fate.

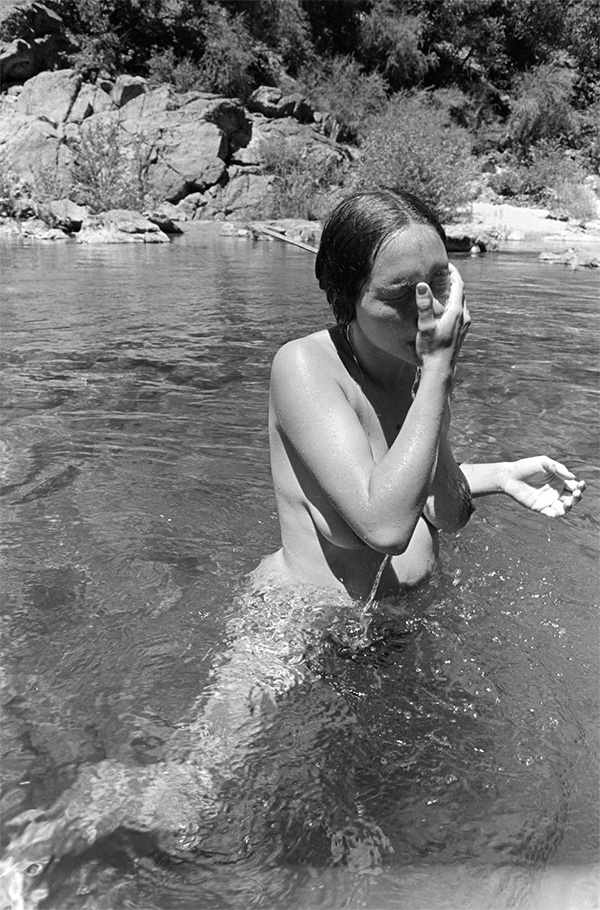

Barbara Hammer's "South Fork Yuba River, California," on view at "Please recall to me everything you have thought of," curated by Eve Fowler.

The show that just came down at Morán Morán was the product manifest of her process study. In a group show called Please recall to me everything you have thought of, Fowler assembled works from each of the twenty women whose practice she recorded for her second film. She grounded her studio portraits with the object result of the artists’ time and energy. Here is Harriet Korman’s painting, here is Virginia Jaramillo’s textile, here is Barbara Hammer’s images of naked women in the Yuba, looking so fresh they could have been taken this summer by all my friends. The group show grounds her studio portraits with the results of the work––discrete pieces of art. The film elevates the objects, honoring artists’ time and energy as much as the market honors their product.

How does one assemble a list of all-women artists? For Fowler, it began with a serendipitous trip to Harmony Hammond’s archives. Hammond founded A.I.R. (Artists in Residence), the first all-female, artist-run gallery in the US, and is similar to Fowler in her concerted effort to bring women to the front. On a Saturday morning, Fowler saw Hammond’s archival treasures, like a purse made out of a friend’s hair, and became acquainted with the early makings of a list of Harmony’s favorite artists and collaborators. This list became the basis for what would grow into the group of women she followed in With It Which It, Part II.

Fowler, with the wisdom that art and curation are inherently political, added and shaped the list of women she wanted to illuminate with a commitment to inclusivity and diversity. Hammond’s list was a starting point. “To get it to be more inclusive, I had to do research, to do the work,” says Fowler. This effort ensured Venezuelan artist Magdalena Suarez Frimkess and Mexican artists Magali Lara and Mónica Mayer were a part of the film and the group show.

Fowler probably enters these studios with a professional calm, able to separate reverence from glorification, but all I could think about was how hard it would be to keep from putting these women on pedestals. I put women on pedestals all the time. The older kids have always been cooler. In sight of the artists farther down the road, with admiration, reverence, jealousy, awe, I go starry-eyed and obsessed. Once, on a night like any other summer night at a bar in Los Angeles, my usually very unflappable lawyer friend Rachel rushed up to me and with wide, serious eyes, breathed into my ear “Naomi Fry is here.” It was like meeting a rockstar. We felt that queer pang that Ilana Glazer’s eponymously named character says of Vanessa Williams’ powerful career-woman in Broad City: “I don’t know if I want to be her or be in her.”

These women are not so different than me––save in time and experience––invaluable and hard-earned gifts that slowly chip away at insecurity. Fowler works from a base line of equal respect for all, which takes the strength of a mature artist. She extends grace to all her fellow artists, and, perhaps most importantly, extends grace to herself.