- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: KAREN ROSENBERG

- Date: JANUARY 11, 2008

- Format: DIGITAL

What’s on the Art Box? Spins, Satire and Camp

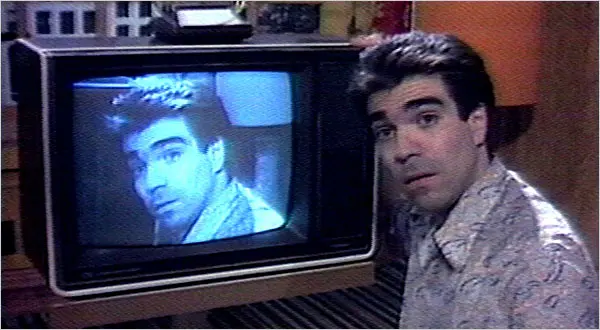

In Mike Smith’s “It Starts at Home,” Mr. Smith’s character suddenly finds himself on TV.

Electronic Arts Intermix

“You are the product of TV,” declares “Television Delivers People,” Richard Serra’s six-minute 1973 video screed of scrolling text set to elevator music. If Mr. Serra were to recreate the piece today, he might call it “People Deliver Television.”

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s new show of single-channel video works, which takes its title from Mr. Serra’s piece, tries to put in perspective the changes wrought by the DVR, YouTube and, more recently, the writers’ strike. Organized by Gary Carrion-Murayari, a curatorial assistant, it combines television-obsessed works from the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s with fresh material from young artists for whom the “idiot box” is just one of many interactive screens.

Clocking in at close to four hours of video (two and a half on a projection screen and another hour or so on a series of television monitors), the show may test the patience of viewers who have grown accustomed to five-minute shorts. Those intent on watching the whole thing may want to do it in two or three sessions. (The longest piece, Alex Bag’s “Untitled Fall ’95,” is 57 minutes, and no clock or little red progress bar is provided.) Most people will simply drift in, catch a few minutes of whatever happens to be playing on the big screen and then move on to the next exhibition.

More committed viewers should start with the three works displayed on monitors (which include the Serra video). One, Mike Smith’s “It Starts at Home” (1982), takes Mr. Serra’s aphorism to a literal extreme. In this mock sitcom, Mr. Smith plays a regular Joe who signs up for cable service and suddenly finds himself on television. The piece is longer than it should be, but worth watching for Mr. Smith’s comically befuddled expressions and for Eric Bogosian, who is the disembodied voice of the tough-talking boss.

Dara Birnbaum’s “Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman” (1978-79) requires only the most minimal attention span. This five-minute sequence strings together clips from the popular 1970s “Wonder Woman” television show, focusing on the magic spin that morphed the actress Lynda Carter into the scantily attired superhero. A mesmerizing stutter effect, timed to the disco soundtrack (“shake your wonder-maker”), makes for a kitschy sendup of Justice League sexism.

The deconstructionist programming continues on the large screen, with Joan Braderman’s “Joan Does Dynasty.” In this half-hour video from 1986 the artist deconstructs that ’80s soap opera, which starred Joan Collins as Alexis Carrington Colby. Talking over the characters with a mixture of contempt and glee, she applies Foucault and feminism to Alexis and the show’s other outrageous schemers. These theories may have fallen out of fashion, but the piece resonates as a critique of yuppie values that could just as easily be applied to “Gossip Girl.”

Lynda Carter spins in Dara Birnbaum’s “Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman.”Electronic Arts Intermix

There is only one representative from the ’90s, perhaps because that decade in video art was dominated by sweeping, multichannel installations. Fortunately, Ms. Bag’s “Untitled Fall ’95” (1995) covers a lot of territory. Ms. Bag poses as a School of Visual Arts student with a dyed red pageboy and a Valley Girl drawl who updates us on each semester of her college experience. Between the segments of her video diary are fake phone-sex ads, skits with potty-mouthed puppets and a slide lecture by a droning, self-obsessed artist who films the contents of her purse.

Ms. Bag’s naïve undergraduate emerges from art school a changed, bitter creature. In one hilarious scene she complains about an achingly hip professor who misquotes a Nirvana song. “Stop selling my culture back to me,” she pleads, neatly encapsulating the Kurt Cobain era.

Ms. Bag’s satiric self-transformations have set the stage for the emerging performance artist Tamy Ben-Tor, among others, but they can sometimes come across as high camp, as is the case with her second piece here. A remix of her shrill Joan Crawford spoof, “Harriet Craig” (1998), with a series of mock commercials from 2004, it targets conglomerates like Procter & Gamble and the company formerly known as AOL Time Warner. One explores the “metrosexual,” a term that now seems as dated as the hype over the merger of AOL and Time Warner.

More up-to-date works take their cues from reality television. In “Dreamtalk,” by Keren Cytter, a young man obsesses about the female star of a dating show as he prepares and shares a meal with his girlfriend and best friend. The other characters interrupt his thoughts with their own syntactically challenged voice-overs, acting out the propped-up love triangles of the reality genre with a disconcerting, Brechtian sense of alienation.

In Kalup Linzy’s “Melody Set Me Free” (2007) the focus shifts to the televised talent competition. A plucky young girl named Patience O’Brien enters a contest of Whitney Houston impersonators, overcoming would-be saboteurs and the disapproval of her strict mother. Mr. Linzy supplies the voices for all of the characters, including the slightly off-key singers. Lurking behind Mr. Linzy’s feel-good story and virtuosic performance is the cautionary tale of Ms. Houston’s decline.

The show’s youngest artist, Ryan Trecartin, doesn’t start with a recognizable genre; he creates his own, with Day-Glo paints, thrift-store costumes and a seizure-inducing arsenal of digital effects. His video “What’s the Love Making Babies For” is not as compelling as his recently exhibited epic “I-Be Area,” though mercifully shorter at 20 minutes. Its adolescent characters declare themselves to be beyond gender and the sexual reproductive system. Since they look like the children of Matthew Barney and David Bowie, it’s easy enough to believe them.

The Whitney’s minisurvey of art about television is only a small, performance-oriented slice. It could have included Paul Pfeiffer’s digitally edited sports and entertainment clips, Nathalie Djurberg’s sadomasochistic Claymations or the recent Turner Prize nominee Phil Collins’s series about disgruntled reality-show participants. In charting such a precise path from Mr. Serra to brand-new work with a YouTube following, it historicizes a medium that is still, as the writers’ strike reminds us, in transition.