- Source: ARTFORUM

- Author: Siddhartha Mitter

- Date: May 2019

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

WAKING LIFE

Siddhartha Mitter on the art of Cauleen Smith

Cauleen Smith, I Cannot Be Fixed, 2017, recto/verso, satin, poly-satin, indigo-dyed silk-rayon velvet, embroidery floss, acrylic fabric paint, satin cord, polyester fringe, poly-silk tassels, sequins, 62 × 48 1⁄2". From the series “In the Wake,” 2017.

VISITORS TO THE 2017 WHITNEY BIENNIAL will remember the banners. Roughly five feet tall by four feet wide, they hung from the ceiling in the museum lobby and the exhibition’s main gallery. Each presented, on one side, a garish image such as a bird bleeding in the sky, or a human eye pierced by a pencil. On the other side appeared a (mostly) confrontational text: MY PATHOLOGY IS YOUR PROFIT; I’M SO BLACK THAT I BLIND YOU; I HAVE NOTHING LEFT. The tough words contrasted with the lush beauty of these objects—the warm colors painted on rich fabric, the sequins and fringes, the phrases embroidered in cursive that imbued them with innocence and immediacy. And when the banners were brought out of the museum one day to be borne in a procession, it was to the joyful accompaniment of spirituals—freedom songs.

Cauleen Smith may not have been well-known to the general public, or indeed to much of the art world, before her banners and their parade were part of the Biennial. But in the Black vanguard—the Afrofuturists and community activists, the artists and writers and theorists imagining ways of living that dignify themselves as Black subjects as well as all of humanity—she is something of a heroine for the breadth and generosity of her work. Many still know her primarily for her filmmaking, her original craft, which she studied at UCLA in the early 1990s. Her feature film Drylongso (1998) is a Black independent cult classic, critically lauded but difficult to find; since then, she has shot at least forty experimental short films.

Cauleen Smith, Leave Me for the Crows, 2017, recto/verso, satin, poly-satin, silk-rayon velvet, metallic thread, polyester fringe, poly-silk tassels, sequins, 78 × 51 1⁄2". From the series “In the Wake,” 2017.

Though these films have long been included in group exhibitions, as well as in solo presentations such as “A Star Is a Seed,” a 2012 show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, it is the slow, steady, sincere broadening of her art practice that is now blossoming into view, a practice that encompasses moving image, installation, textile, drawing, and performances that double as community gatherings. An exhibition of recent work in multiple media, “Give It or Leave It,” originated last fall at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, traveled to the ICA at Virginia Commonwealth University, and is on its way to the Frye Art Museum in Seattle before heading to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. That iteration will be a homecoming: Smith lives in Los Angeles and teaches at CalArts. Meanwhile, another major show, “We Already Have What We Need,” bringing together recent work with several earlier films, opens this month at MASS MOCA.

Smith’s politics are serious, but even more fundamental to her outlook is an ethic of care, both of oneself and of others.

Smith was born in Riverside, California, in 1967, but grew up in Sacramento. She was an undergraduate at San Francisco State University, studying film at a time when the Bay Area, having generated key strands of the Black Arts Movement and nationalist politics, was still a redoubt of Black bohemia. Smith’s parents are both social workers who moved to the West Coast from their native Tennessee. In Sacramento, they purchased a Joseph Eichler home—a residence in one of the modernist subdivisions that the developer scattered about California. On principle, Eichler rejected the racial discrimination then prevalent in real estate transactions, and as a result Smith grew up in a diverse community; she remembers a gay couple who lived down the street, and many of her friends were Asian American. In California, Smith’s father got into bonsai and became a master of the craft, along with suiseki, the Japanese art in which connoisseurs go in search of rocks with felicitous shapes. She prizes the pedestal-mounted championship rocks that he has given her—bulbous, serrated, cavernous—though she scolds herself for not displaying them properly. When I met her in her studio, she showed me a copy of Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers, Leonard Koren’s 1994 book on the Japanese aesthetic of “things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.”

The intentional positioning of objects is part of Smith’s art. One format that she has honed in recent years—employed in several works in her current exhibitions—involves selecting items that carry personal or symbolic meaning and carefully arranging them on a tabletop. Also on the tabletop are monitors that play video footage—both her own and found—and closed-circuit cameras that capture the moving images as well as the objects and then project it all onto a wall.

Cauleen Smith, Epistrophy, 2018, multichannel video (color, sound), four CCTV cameras, four monitors, projection, custom wood table, taxidermied raven, wood figures, bronze figures, plastic figures, books, seashells, minerals, jar of starfish, Magic 8-Ball, maneki-neko, mirror, metal trays, plaster objects, wood objects, wire object, fabric, glass vase, plants. Installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Photo: Constance Mensh.

Epistrophy, 2018, for example, which borrows its title from a Thelonious Monk composition, presents four monitors placed at right angles at the center of a round table. The video tracks cut across various landscapes: a railroad in the desert; trees in blossom, seen up close; the Los Angeles hills at dusk; riders on a bus in Kenya; elevated rail girders in a city, perhaps Chicago; cloud formations; the curve of the earth as viewed from space. Across the tabletop Smith scattered books, bracelets, stones, plants, dolls, and a taxidermied crow on a pedestal. She positioned African statuettes within the cameras’ sights. All four projections then appear on a wall, slightly overlapping, with the statuettes in silhouette, standing like impassive sentinels as the scenery rushes by. On one level, the work is immersive—the images fill the room like a kaleidoscope—but the table registers as an altar: Every item is sacral. It is a telescopic experience, uncannily intimate—suggesting, perhaps, how we might make spaces meaningful for ourselves in this unsettled world.

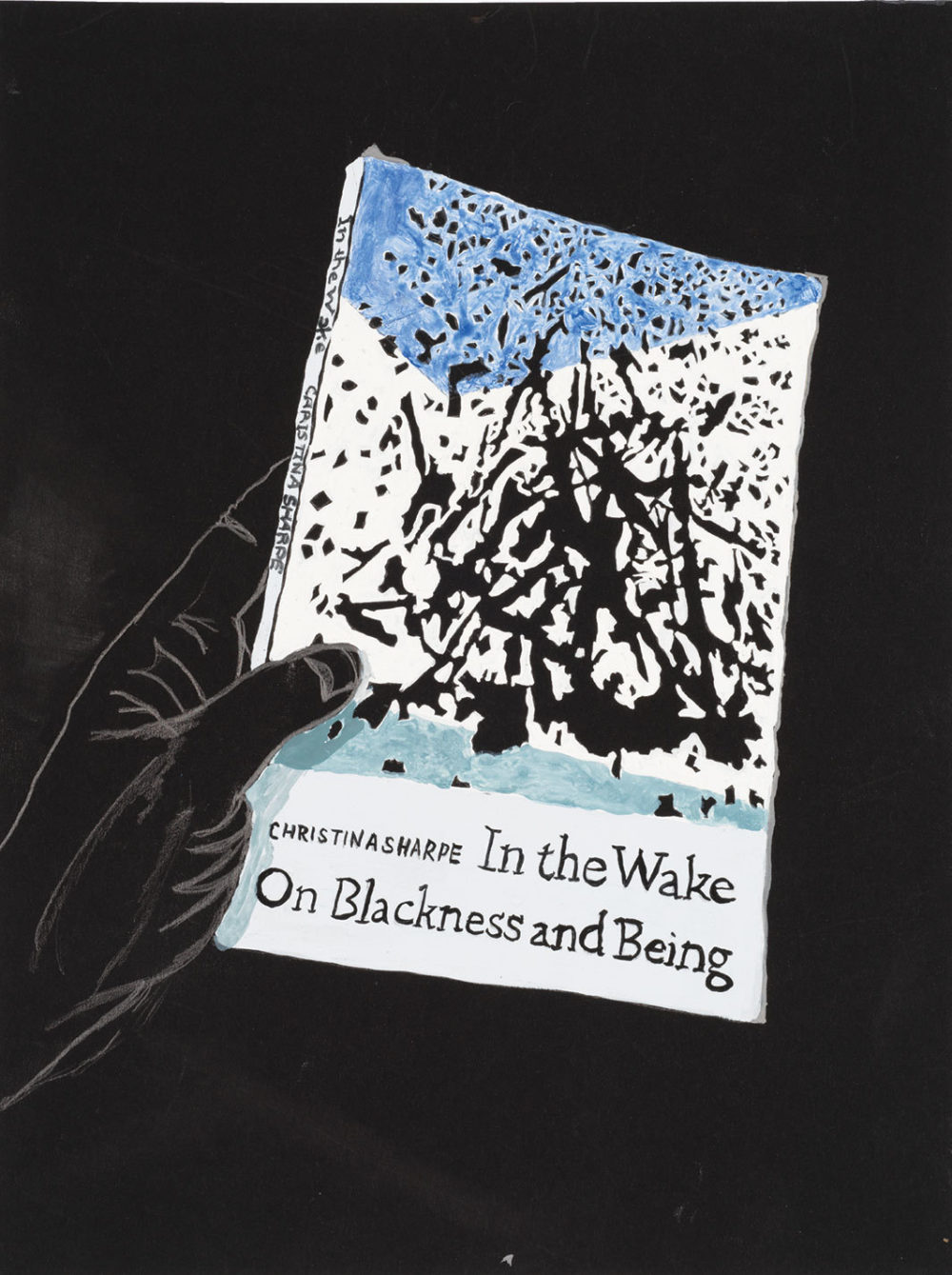

Cauleen Smith, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, 2019, gouache on paper, 12 × 9". From the series “BLK FMNNST Loaner Library 1989–2019,” 2019.

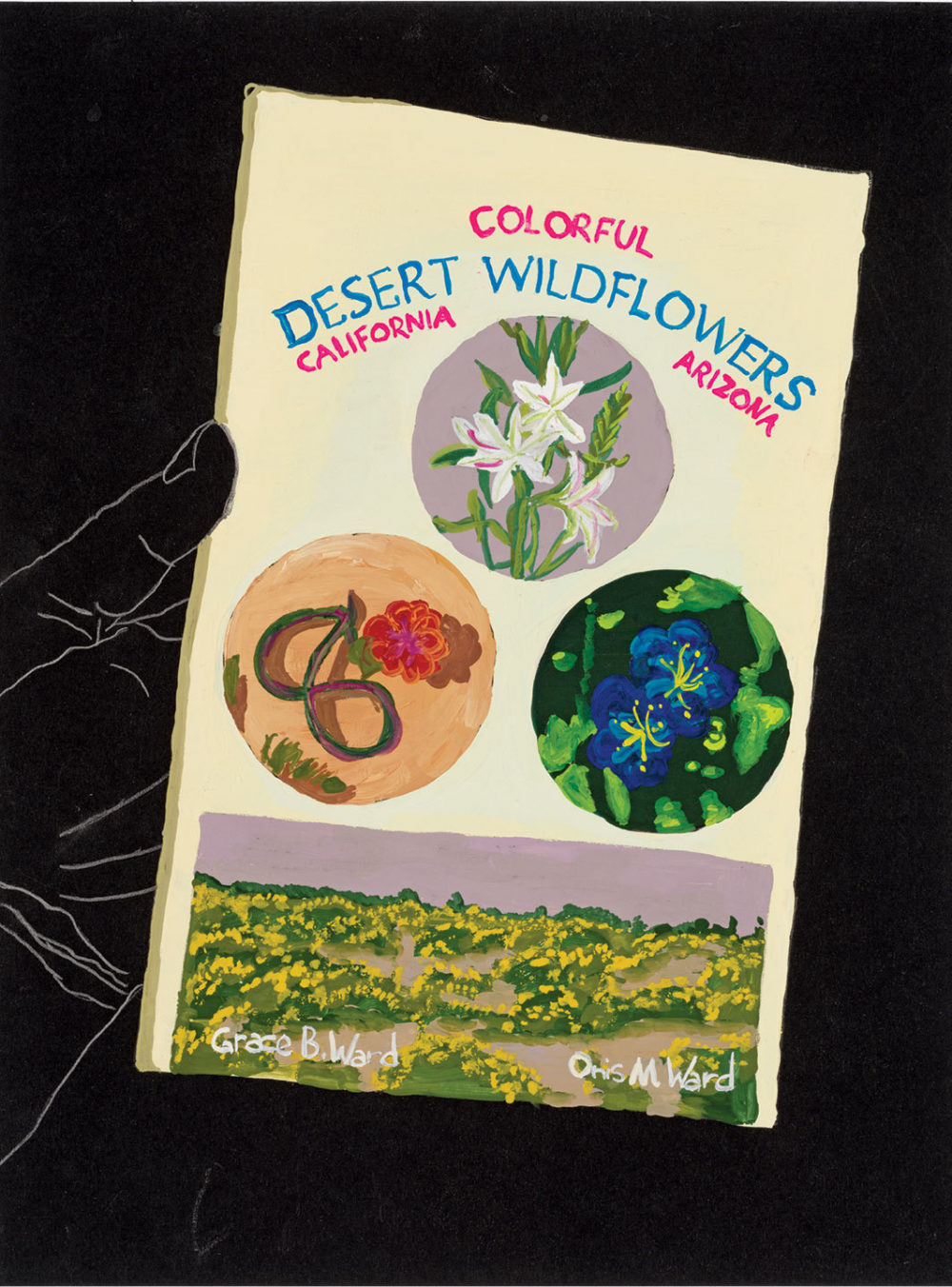

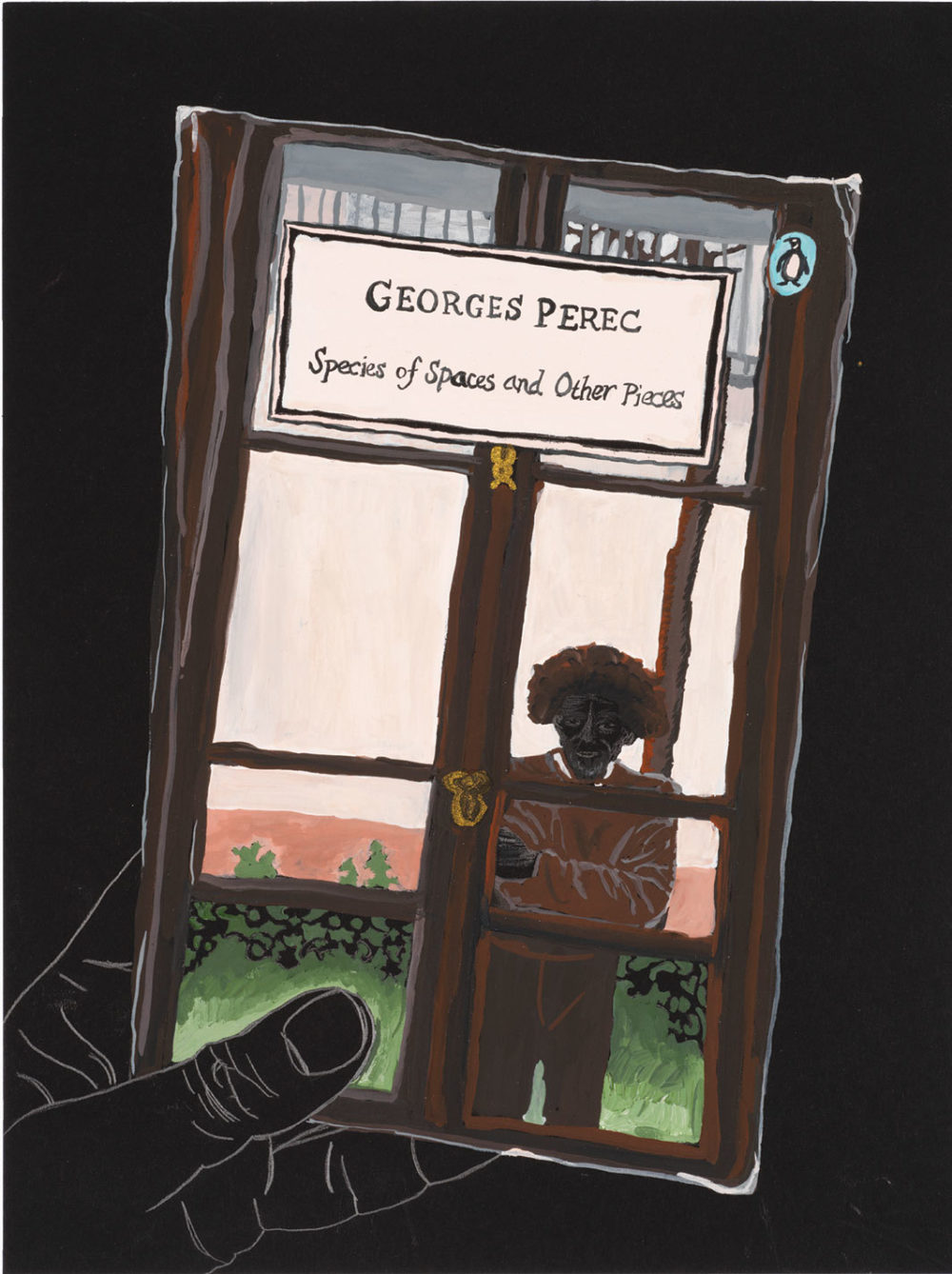

An animating force in Smith’s work is Black feminism—its genealogies, its ways of seeing and being—and her evolution as an artist has been guided by its spirit. Many of the books featured in “BLK FMNNST Loaner Library 1989–2019,” 2019, a new series of thirty gouache-and-graphite works made on letter-size black paper, come from that stream. Each drawing depicts a work of literature dear to her, proffered by a Black hand: Lose Your Mother, by Saidiya Hartman; The Origin of Others, by Toni Morrison; Land to Light On, by Dionne Brand. But she also includes a work by French novelist Georges Perec, another by the Tanzanian leader Julius Nyerere, and a guide to California desert wildflowers. Smith made a similar series in 2015, quickly and on flimsy white paper, emphasizing classics of Black political thought; she intended it as a gesture of solidarity and of gentle mentorship for young Black Lives Matter activists in Chicago. Titled “Human_3.0 Reading List,” it was later exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago. The new series is, in Smith’s own words, less didactic than “Human_3.0”—not a syllabus, but a catalogue of influences and affections.

Cauleen Smith, Colorful Desert Wildflowers: California and Arizona, 2019, gouache on paper, 12 × 9". From the series “BLK FMNNST Loaner Library 1989–2019,” 2019.

Smith’s politics are serious, but even more fundamental to her outlook is an ethic of care, both of oneself and of others. In Drylongso, shot in Oakland and completed in 1998, two young women, brought together by a chance incident, look out as best they can for each other and for the community. Pica (Toby Smith) is broke and in art school and lives with her dysfunctional mother. Tobi (April Barnett) is better off but being stalked by a violent ex-boyfriend. Meanwhile, a slasher has been roaming the streets, attacking men and women; however, activists—embodied by Pica’s friend Malik, a tragic figure—are focused on society’s many threats to Black men, held up as an “endangered species.” Smith’s regret about Drylongso is that she could not forestall masculinist interpretations of the story, which reduced her female protagonists—and thus herself—into helpmeets. “People thought the film was about Black men,” Smith told me. “At that time, that was the whole discourse. It’s easier to see the movie now for what it intended because there’s a language for it now.”

Cauleen Smith, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, 2019, gouache on paper, 12 × 9". From the series “BLK FMNNST Loaner Library 1989–2019,” 2019.

Even if she didn’t know it then, Smith was contributing to building that language. Pica enjoys walking the streets taking Polaroids of strangers, with whom she shares the prints; she is a stand-in for Smith, who once did the same thing. The character is falling behind in her photography course. She cuts class; she insists on using the Polaroid instead of a more professional camera; she drags her feet when it comes to her thesis exhibition, because the format bores her. In the end, she organizes her show as a pop-up sculpture garden for the community in an overgrown empty lot. The Polaroids, some of them memorials for the fallen, adorn fantastical sculptures of found and repurposed materials. Watching the film now, one has the uncanny feeling that Smith was announcing her future moves through Pica’s instinctive decisions in her search for autonomy.

Still from Cauleen Smith’s Drylongso, 1998, 16 mm, color, sound, 82 minutes.

Drylongso was selected for the Sundance Film Festival in 1999 and won awards at SXSW and the Urbanworld Film Festival, but received no commercial traction. Like Julie Dash, the director of Daughters of the Dust (1991), Smith found that Hollywood had little interest in her Black feminist sensibilities. She spent several years ghostwriting scripts and pitching her own movies to no avail, before leaving Los Angeles in 2001 for her first teaching job at the University of Texas at Austin. To this day, she says she doesn’t watch movies except on airplanes, but her work in experimental film, a practice she had begun before Drylongso, continues.

“Future and past, you want to hold all of that. You want to celebrate, you want to protest, you want to do all at once.”—Cauleen Smith

In Austin, Smith became interested in presenting films inside museums and galleries. She was galvanized by conversations with curators, whom she found far more open than her former interlocutors in the movie industry, and guided by the video and performance artist Michael Smith, a senior colleague in her department who took her under his wing. I Want to See My Skirt, 2006, which runs to seventeen minutes, was the third film she made as part of an installation. It is a formal layer cake inspired by a set of photographs by the Malian master Malick Sidibé. Smith asked the poet A. Van Jordan to write texts based on these images, which she then had translated into French and read aloud to serve as the film’s narration. Shot in Texas at locations that look remarkably West African, from the wooden shop stalls to the dusty terrain, Smith’s film restages the photographs and builds a story from them. In one scene, based on Sidibé’s image of a young man and woman posing playfully on rock heaps by the Niger River, Smith’s protagonists toss beanbags at each other, which accumulate on the ground. Smith told me that her interest in installation was piqued by a feeling that her film props deserved further uses—that they somehow demanded to pop out of the screen. When the work was shown in December 2006 at the Austin art venue testsite, Smith installed it alongside a huge pile of beanbags, many of which she gave away. She is reprising this piece for the MASS MOCA show, again with one thousand beanbags handcrafted from African wax-print fabric.

Still from Cauleen Smith’s I Want to See My Skirt, 2006, Super 8 transferred to digital video, color, sound, 17 minutes 30 seconds.

Another formative moment for Smith was a monthlong stay in New Orleans in 2008, where she was invited by the artist Paul Chan to participate in a series of post-Katrina projects. While the cultural and economic dislocations that followed the hurricane were apparent to her, she did not have the burden of personal anger or sadness born of knowing the city before the storm. Smith’s forty-eight-minute The Fullness of Time, 2008, is, in her words, a “science-fiction rumination on space, place, and posttraumatic stress.” It is a clear-eyed account of disaster capitalism, but it arcs away from pessimism or dystopia. Images of flood, destruction, and characters adrift give way to both what preexisted Katrina and what also survives it: Mardi Gras Indians, church services, and the presence of music, which swells until the sounds of jazz saturate the film. Returning to New Orleans in 2014, she made a short, H-E-L-L-O (2014), comprising a series of shots in which a single musician improvises off John Williams’s five-note sonic leitmotif for Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Always keen on science fiction, Smith here bridges bold, even impossible, imaginings of the future and the history of jazz, stretching back to Africa. The film exemplifies the ethos of “Ancient to the Future”—the mantra of the avant-garde Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), whose music she grew up hearing in her family home.

Still from Cauleen Smith’s H-E-L-L-O, 2014, digital video, color, sound, 11 minutes 6 seconds.

Smith attributes her use of the processional to New Orleans’s parade culture and to its textured Black community life. She felt the resonance of that culture in Chicago, too, the emblematic destination of the Great Migration, when she held a residency at Threewalls in 2010; a year later, she moved there. Her initial work in Chicago focused on Sun Ra, the great bandleader and mystic who formed his Arkestra in the city in the 1950s, having migrated from Alabama after the war. A precursor and vital influence on the AACM, Sun Ra famously declared he came from Saturn, and looked from ancient Egypt to outer space for alternatives to Eurocentric knowledge systems. Beyond the forms of the music, the wild costumes, and the performances, his art functioned as means to freedom, from economic self-determination (he shared a house with his musicians and founded his own record label) to a deeper assertion of free Black thought.

Cauleen Smith, Space Is the Place (A March for Sun Ra), 2010, HD video, color, sound, 10 minutes 56 seconds.

Smith made several films in homage to Sun Ra, following the bandleader’s footsteps, shooting meditative passages in the Chicago cityscape, and layering in music by him and others as well as audio from interviews with people who remembered his time there. One of these films, Black Utopia LP (2011–), comes with a freestanding album of interviews and Sun Ra studio rarities. In another, The Way Out Is the Way Two (14 short films) (2010–12), a pair of extraterrestrial humanoids with fiery orange hair in black outfits move around the city in search of music to nourish them. While in Chicago, Smith also organized a series of flash-mob events in which Black marching bands played Sun Ra’s music unannounced in public spaces. Space Is the Place (A March for Sun Ra) (2010) documents the first such intervention, and featured the musicians of Rich South High School surging into a commercial plaza in Chicago’s Chinatown while performing the visionary’s most famous tune, “Space Is the Place.” By refusing to seek municipal permission for these events, Smith announced a prior, communal claim to the city as both a shared landscape and a psychic domain. In the process, her own work acquired another dimension: She no longer simply filmed the city; she activated it.

Cauleen Smith, Black Utopia, 2011–, 800 35-mm slides, double vinyl LP, 88-minute performance.

These years also coincided with the rise of the national Black Lives Matter movement, which galvanized the ongoing work of local organizers in Chicago who were fighting gun violence and the scandal-ridden police department. Black women, in particular, spearheaded these efforts. Protest culture, with its performative aspects, processions, and visual messaging, stirred Smith to contribute to the work while expanding its stakes. “Protesters always make gorgeous banners,” she told me. “What if I made it as if it was forever? It’s not about power, it’s about holding the space indefinitely. Future and past, you want to hold all of that. You want to celebrate, you want to protest, you want to do all at once.” Some of her banners are heraldic and authoritative, as in the 2017 Biennial; others are connective, meant for two people to hold up, bearing warmer messages such as APPRECIATE YOU IN ADVANCE.

Cauleen Smith, The Way Out Is the Way Two (14 short films), 2010–12, digital video and 16 mm transferred to digital video, color, sound, 82 minutes.

The recognition Smith has received of late acknowledges the level of mastery she has attained, but it suggests, too, that the world is finally on her wavelength, tuning in to the same signals through the static.

Those she exhibited in the Biennial are collectively titled “In the Wake,” after the book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), by the scholar Christina Sharpe, who theorizes the “wake”—in all its maritime, funereal, and cognitive meanings—as a frame for understanding and enacting Black existence in an anti-Black world. It is a heavy concept, necessarily so, that derives its original metaphor from the slave ship. But what Sharpe calls “wake work” is not simply mourning. Rather, she writes, it is the effort to “imagine new ways to live in the wake of slavery, in slavery’s afterlives, to survive (and more) the afterlife of property.” Inside those parentheses lies possibility. “I am trying to find the language for this work, find the form for this work,” Sharpe writes. Smith’s banners propose one such form.

In Sojourner (2018), Smith’s latest film and perhaps her most beautiful, six banners—made of translucent orange vinyl, onto which are sewn letters in different colors of light-absorbing velvet—reappear in multiple locations. Together, they spell words from a text by Alice Coltrane—known in her spiritual life as Swamini Turiyasangitananda—in which she relates a divine revelation: “At dawn, sit at the feet of action. At noon, be at the hand of might. At eventide, be so big that sky will learn sky.” From site to site, the film touches on a group of nonconformist, deeply humane figures, from different places and periods, among whom Smith has discerned connections. One is Coltrane; another is Rebecca Cox Jackson, the nineteenth-century mystic, who lived with the Shakers in upstate New York and founded a Black Shaker community in Philadelphia. A third is Noah Purifoy, the assemblage artist, who retired late in life to the California high desert and built an extraordinary outdoor museum of found-material sculptures and edifices there.

Still from Cauleen Smith’s Sojourner, 2018, digital video, color, sound, 22 minutes 41 seconds.

We see the orange banners at a protest in Chicago, where the activist Dr. Barbara Ransby is speaking. In California, they are carried along the beach and to the Watts Towers, which the artist Simon Rodia bequeathed to the community. Midway through the twenty-two-minute film, the action settles at the Purifoy site. Twelve women in colorful bohemian outfits walk the banners among the sculptures, the letters casting strong shadows in the desert light. Later the women sit on folding chairs before a transistor radio, and listen to a section of the Combahee River Collective Statement, the Black feminist manifesto issued in 1977. The section culminates this way: “We reject pedestals, queenhood, and walking ten paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.” Music by Alice Coltrane swells before a final tableau.

Considering how multifaceted Smith’s oeuvre has been thus far, Sojourner is a remarkable synthesis: Here is Pica, in spirit, in her improvised sculpture garden; here are places where Smith has lived; here are the ideas and techniques she acquired along the way. The recognition Smith has received of late acknowledges the level of mastery she has attained, but it suggests, too, that the world is finally on her wavelength, tuning in to the same signals through the static. Her work long ago slipped the shackles of category. Its message is one of care and mutuality, intention and improvisation, for art and for life.

Siddhartha Mitter writes on contemporary art and cultural issues.