- Source: HARPER'S BAZAAR

- Author: STEVEN MOOALLEM

- Date: OCTOBER 6, 2022

- Format: PRINT AND ONLINE

Two Artists Are Reimagining the Future of Lincoln Center

With a pair of new public-art projects, Nina Chanel Abney and Jacolby Satterwhite herald the arrival of new era for one of America’s preeminent cultural institutions—by reckoning with its complicated past

Nina Chanel Abney. Rick Owens strobe jacket, $7,125, and shirt, $410; rickowens.eu. Esenshel bowler hat, $555; 917-806-2378. Necklace, her own.

XAVIER SCOTT MARSHALL

Jacolby Satterwhite. Yohji Yamamoto coat, $7,450, and blouse, $860; theshopyohjiyamamoto.com. Earring, his own.

XAVIER SCOTT MARSHALL

Before Lincoln Center was a place, it was an idea. Hatched in the 1950s as part of a controversial “urban renewal” project shepherded by then New York City planning commissioner Robert Moses, the concept was to build a new campus to house the city’s top arts organizations, modeled on the great cultural squares and kunsthalles of Europe: a stage—or rather a series of them—upon which American excellence in the classical arenas of music, theater, opera, and dance could be performed. Moses, once described in a 1939 profile in The Atlantic as a “Paul Bunyan of an official,” earmarked a piece of land for the development in San Juan Hill, a bustling neighborhood with large Black and Puerto Rican communities nestled between 59th Street and 65th Street on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. San Juan Hill was already teeming with artists—great ones, in fact, who were in the process of shaping some of the 20th century’s most distinctly American forms of creative expression. Eugene O’Neill lived there. So did Thelonious Monk. It was the birthplace of bebop and the Charleston. Moses, though, had the entire area demolished to make way for the construction of Lincoln Center, which broke ground in 1959, displacing more than 7,000 families and 800 businesses.

The story of how San Juan Hill was effectively razed—and in many ways erased—is one that resonated deeply with both Nina Chanel Abney and Jacolby Satterwhite. Last fall, the artists were each invited to submit proposals for public-art installations to inaugurate the reopening of David Geffen Hall, home since 1962 to the New York Philharmonic orchestra. The building, formerly known as Avery Fisher Hall (and before that, Philharmonic Hall), was shuttered in March 2020 as the pandemic descended. But it has since undergone extensive renovations, thanks in part to a substantial gift from entertainment mogul Geffen, whose name now graces its entrance. The $550 million in refurbishments preserved the glass-walled exterior and tapered marble columns of the late architect Max Abramovitz’s original design but involved substantial interior modifications to improve the hall’s acoustics and make the space feel more intimate and accessible. The lobby will feature an open plan with a 50-foot media wall where people can view live performances for free, as well as an Afro-Caribbean restaurant from chef Kwame Onwuachi. The coming season will kick off October 8 with the premiere of San Juan Hill: A New York Story, a new multimedia work by Trinidadian-born jazz trumpeter Etienne Charles conceived as an ode to the neighborhood. October will also mark the unveiling of the works by Abney, 40, and Satterwhite, 36, the first in a planned rotating series of pieces commissioned by Lincoln Center in conjunction with the Studio Museum in Harlem and nonprofit Public Art Fund. Abney’s installation, which will cover the entire 65th Street facade of David Geffen Hall, will pay tribute to the people of San Juan Hill and the powerful spirit of the community. Satterwhite’s piece, a video that will span the length of the media wall, will merge elements of Lincoln Center’s history with notions of the future and possibility.

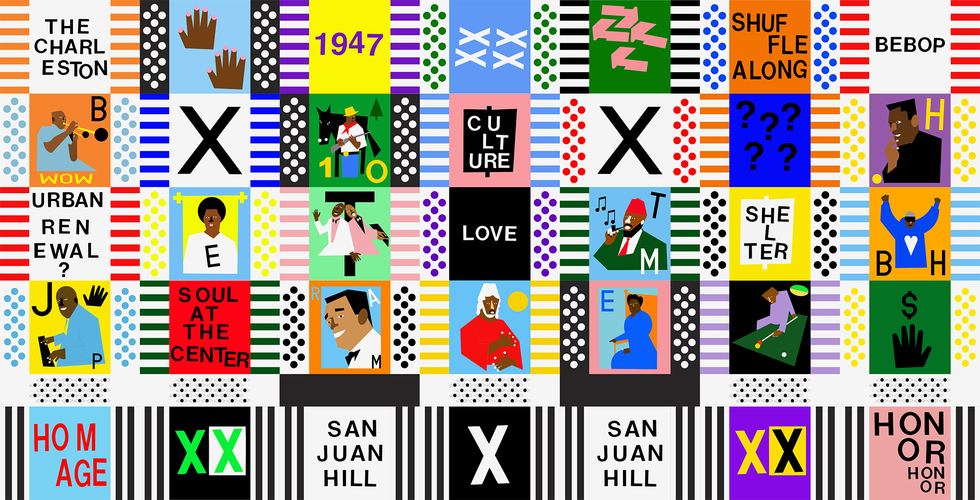

Nina Chanel Abney, Study for San Juan Heal, 2022. Courtesy Nina Chanel Abney Studio, Inc. The final installation, San Juan Heal, was commissioned by Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in collaboration with The Studio Museum in Harlem and Public Art Fund for the new 65th Street façade of David Geffen Hall.

NINA CHANEL ABNEY

Abney, whose colorful large-scale paintings often touch on subjects like race, gender, sexuality, and violence, began as she usually does when she starts a new body of work: by immersing herself in research. She was already aware of jazz greats like Monk, Herbie Nichols, and Benny Carter and musical-theater pioneers Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, who all lived in San Juan Hill. But she soon learned about other residents, like expeditioner Barbara Hillary, the first Black woman to reach both the North and the South Poles, and Edith Carter and Elizabeth Tyler, Black nurses who helped found the Stillman House Settlement to provide care for the people of San Juan Hill. She also studied the details of the 1898 Battle of San Juan Hill in Cuba, a conflict during the Spanish-American War that was fought and won by a contingent that included a number of Black soldiers, many of whom later settled in New York. Abney read about the economic conditions in the 1930s that led to San Juan Hill becoming home to a big public- housing project that later fell into disrepair and how its designation in 1947 as a “site for redevelopment” precipitated its demolition. She was also enthralled with the powerful resistance to the plan that emerged from within San Juan Hill.

Working in her Jersey City, New Jersey, studio, Abney decided to create a gridlike assemblage of images, texts, and language pulled from old protest flyers and posters that would be printed on vinyl panels and installed on the north side of David Geffen Hall. “It just seemed like a culturally rich neighborhood,” says Abney. “So it was about trying to figure out a new way to share that—and in a way where people learn more about the people who were a part of that neighborhood and their contributions,” she explains. “I feel like we have to acknowledge the history because I’m not quite sure if it’s really been acknowledged enough.”

Satterwhite embarked on a similar fact-finding mission. He plunged into the Lincoln Center archives, searching for not just landmark moments in the annals of the hall but women and artists of color who had appeared or had their compositions performed there. “The history of the Philharmonic and the hall is heavily curated—very myopic and narrow,” Satterwhite says. “I wanted to see if there was a possibility to mine a different history of things that maybe have been swept under the rug and champion lesser-known people, women, queer people, and people of color.”

Jacolby Satterwhite, an in-progress still from An Eclectic Dance to the Music of Time, 2022. HD color video and 3D animation. © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York. The final installation, An Eclectic Dance to the Music of Time, was commissioned by Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in collaboration with The Studio Museum in Harlem and Public Art Fund for the Hauser Digital Wall in the lobby of David Geffen Hall.

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE

Satterwhite’s best-known works incorporate elements of performance, CGI, and digital animation, but he started out as a painter. He immediately began to think about the depictions in high-Renaissance and early modernist pastoral paintings, like Titian’s Le Concert champêtre (circa 1509) and Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), of young artists, poets, and musicians gathering in a bucolic setting to perform. To Satterwhite, these figures seemed almost mythological. He started to envision a virtual landscape populated with music and dance students from local educational institutions like the Ailey School, the Juilliard School, and LaGuardia High School. He then filmed the students performing against green screens on a soundstage before knitting them into his imagined world, which he digitally rendered in his Brooklyn apartment by working off a mix of Googled maps and images and archival videos. “They’re metaphorically about representing the present in the future,” Satterwhite says of the students. “They also are the conduit to bring a different kind of community into Lincoln Center, because it’s sort of like a yearbook. They can see themselves as a participant in something that usually has omitted people that look like them.”

Abney often spurs her creative process by loading up on images and ideas. “I work almost completely intuitively when it comes to painting,” she says. “It’s almost like a puzzle, a game, in the creation.” The impetus is usually small. “It could just be something happening in the news, or something random I read, or just even based off pure imagery or something I want to see,” she says, pointing to a group of pieces she’s working on for “Big Butch Energy,” a solo show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, in November. “It’s based on some of my own experiences, but it was a conversation amongst some friends that sparked the show,” she says of the exhibition, which explores the ways that gender is perceived and performed within the context of social rituals. “I’m thinking about frat houses and sororities,” she explains. “That’s what’s swirling around for me right now visually—and movies like Animal House.”

The public nature of the David Geffen Hall installation inspired Abney to contemplate how she might engage with viewers differently. “If it was in a gallery setting, I might have been more of an agitator about it,” she says. “But I feel like all my work instigates a bit.” She’s now exploring ways of extending the piece. “I have an idea of doing a zine or some digital component where you can scan something and get more information, because I don’t want it to be something where someone’s just looking at it and thinking it’s cool. I want them to be engaged enough to find out more.”

In creating his video, Satterwhite scoured the vast library he is constantly assembling of images, videos, snippets of sounds, maps, schematics, and drawings. It’s a practice he has maintained for years; one of his earlier works, The Matriarch’s Rhapsody (2012), was created using thousands of sketches and recordings made by his late mother, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia. He views the David Geffen Hall project as a natural outgrowth of the way his practice has begun to evolve. “I think that I’ve gotten more direct about things politically after Covid-19 and the summer of 2020,” he says. “I remember having to do a solo exhibition that fall and feeling a great deal of uncertainty and fear and panic and chaos. All I could do was just walk among the people who were protesting outside of my apartment and in the park during the pandemic. … I was just recording everything. I was building an archive on my iPhone, and a lot of that footage ended up becoming the landscape that I was painting from or modeling from to generate new worlds.”

Satterwhite says that kind of social practice is becoming an even bigger part of his work. “I really enjoyed collaborating with 120 dancers and musicians who were giving their all for a small video loop. There was something about that exchange that was really powerful for me,” he explains. “I want them to feel like, ‘This is my first time in Lincoln Center, but this isn’t the last.’ ”