- Source: Frieze Magazine

- Author: LOUISA ELDERTON

- Date: October 21, 2015

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Torey Thornton at Modern Art, London, UK

Exhibition Review

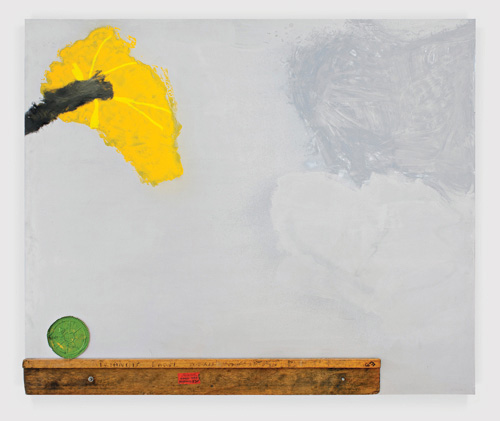

The paintings in Torey Thornton’s first UK solo show wanted to play: 17 ambitiously scaled works on paper and wood panel jostled for centre stage across Modern Art’s three gallery spaces. Even the exhibition’s cryptic title had playful overtones: ‘Kneed a Sea Ware Groin’ conjures two bawdy sea creatures wrestling in a cartoon embrace. Thornton’s large-format works depict bold, confident forms that oscillate between figuration and abstraction. A nod to the cartoon-like renderings of painters such as Philip Guston is palpable – intentional childlike naiveté offset by witty titles. In First Cynthia (2014), a frenetic fly buzzes towards a pristine platter of grapes – still life humorously interrupted – while in As Troll No Mic Call, Ring (2015) the sun reaches out to stroke the earth, its golden beams like long limbs. Elsewhere, less obviously identifiable shapes also recall bodily organs, or are they landscapes? In First, After I saw Elvis Looking At Me and Imagined Him Looking To Andy (2014–15) a canary-yellow cellular mass is streaked with veins of electric lemon like a cartoon lung or, perhaps, a lake seen from above.

Bright colours pop throughout: bubblegum-pink offset by turquoise-blue and apple-green, accompanied by great swathes of silver and gold. Images and shapes are repeated across paintings and found objects are playfully integrated into their compositions: rectangular strips, bulbous round forms, a sign saying ‘Do Not Litter’, a My Little Pony hung upside down, its purple tail pointing up. The cadmium lines of First Cynthia recur enlarged in Once You Become a Real Yorker Are You Still Southern (Second Broken Rule) (2015), like road markings dancing on black asphalt and beginning to dissolve in a magic mushroom-laced haze. Repetition also featured within works, for example in the form of stacked wooden beams or gridded sheets of paper, lending the whole exhibition a certain rhythm.

Torey Thornton, First, After I saw Elvis Look At Me And Imagined Him Looking To Andy, 2014–15

Aluminium enamel paint, oil, wood, spray paint and collage on wood panel, 1.8 × 2.2 m

Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

Contemporary painting often brings to mind the virtual realities of our internet-mediated world (think, for example, of the work of Ida Ekblad, Mary Ramsden or Michael Staniak). Thornton’s paintings are rooted in physical matter, yet his characterful objects sit on the surface against monotone backgrounds reminiscent of flat computer screens. Many depict the simple, almost archetypal, forms that might appear in a Google image search for ‘orange’, ‘sun’, ‘earth’ etc. His aesthetic calls to mind Photoshop actions: draw around one form to cut it out and overlay it on another, copy and paste, enlarge the size. The program’s sidebar of tools is recalled more explicitly in the right-hand purple and grey strip of Baby Grand Barrier (2015). As Thornton indicates, however physical the action of painting remains, it cannot escape the virtual realm and its influence on visual culture.

Two distinctive works were comprised of found slatted-wooden panels. One is striped with yellow and red, the other a rich green plane studded with masonry screws: Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘combines’ meet Jasper Johns’s ‘flags’. Drag Sass Cross (2015) presents a similarly idiosyncratic case: green polyester play mats take the place of canvas, lending the paint a rubbery texture. Thornton follows in the footsteps of these 20th-century American titans, who used popular iconography to symbolize the blurry intermingling of art and life. Thornton’s conflation of the two draws, instead, on the mediation of the computer screen – each of us, after all, enacts a form of collage on a daily basis, layering windows, tabs and images on our computer desktops. His titles, often reminiscent of quick-fire quips posted on social-media sites, seem to corroborate this background narrative.

Aerial views appear in works such as Name Your Yellow Lab Cabbie (I Didn’t See But OD) (2015) or the colloquially titled Snipers Vacay Too (2014) – a topography of sea and shoreline. In the former, a palette of shimmering golds and ochres suggests plots of land. I was reminded of the recent bird’s-eye images of the destruction of the ancient city of Palmyra in the Syrian desert: bare rectangles of dusty land, no monuments in sight. The smoke-chugging, colossal tank-like form in You Say Militia, I say Melissa, Or Something. Mostly About Striping (2015) is surrounded by a strange melange of galloping equestrian-statue horses, conjuring a feeling of warfare from a Command & Conquer-type videogame. At first, Thornton’s canvases seem not to take themselves too seriously but, further considered, they reproduce the mood of our time, in which war, fantasy and pop culture all combine – often on the same newsfeed, one window visible beneath the other.