- Source: HYPERALLERGIC

- Author: NICOLE RUDICK

- Date: JULY 01, 2017

- Format: DIGITAL

The Power and Complexity of Children’s Art: An Interview with Brian Belott

Children’s scribbles may appear random but they often repeat shapes, like the mandala or the Greek cross, that suggest the beginning of language.

Installation view, Brian Belott’s Dr. Kid President Jr. at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise. (Images courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.)

Brian Belott’s work is a lesson in the eccentric and ecstatic. His aesthetic is evident not only in his choice of colors (every hue under the sun, frequently in a single painting) and materials – which have included artificial bread, socks, calculators, hair, aquarium rocks, shoelaces, remote controls, and a lot of cotton batting – but also in his intense curiosity in the margins of culture and his interest in the amateur aspects of art. In the early and mid nineties, Belott attended the Cooper Union and the School of Visual Arts in New York, but his paintings, even now, display an unschooled, adventurous, and exuberant sensibility. He is fearless in his experimentation.

His latest exhibition — Dr. Kid President Jr. at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise — is a case in point. This is the third iteration of the show (he first mounted it at 247365 in New York in 2015, and then at Pancake Epidemic in Los Angeles in 2016) and the largest by far. The show is tripartite and hung salon-style in the gallery’s high-ceilinged space: some three hundred drawings and paintings from the Rhoda Kellogg International Children’s Art Collection; fifty of Belott’s own paintings; and multimedia works produced in an art classroom, inside the gallery, by local New York City schoolchildren. Kellogg (1898–1987) was a psychologist and early-childhood educator and the director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Preschool Learning Center (part of the Golden Gate Kindergarten Association, in San Francisco) for nearly three decades. During that time, she amassed a staggering collection of art made by children between the ages of two and eight. Belott’s discovery of her collection intersected with his own work at the time and forms the basis of this new exhibition.

Last week, the artist walked me through the show, as a group of first graders from P.S. 129 chattered and painted in the art classroom.

Nicole Rudick: Why a show of kids’ art?

Brian Belott: Kid’s art’s been a long-time passion, something I’ve always loved — not only the innocence, but the exuberance of how things are done. A child wakes up in the morning with so much energy, and I try, in my own practice, no matter what I do, to tap into that hyper-spazzy energy that slowly gets shut down as you enter the adult world. As an artist, I’m into celebratory stuff. I’d much rather create a dance party than a pity party. I’m not too interested in Francis Bacon, for instance, because I don’t like to deal with the torture of being a mortal meat pocket, you know? I was lucky enough that my parents kept a lot of my own art, so I have maybe two hundred examples of stuff I did when I was a kid. When I started going to college, I tried to copy my own childhood work. That didn’t really work out.

NR: What was the problem?

BB: It felt too loaded, because it came from my psyche when I was young – pirates, laboratories, and robots, Star Wars. And when I was confronted with that psyche, as an adult, at Cooper, it was a little too much. It was easier to find children’s art on the street. I lived in New Jersey at the time and was surrounded by schools, so I would just dumpster dive. My mom was a teacher, and at the end of her school year I would go to her classroom and whatever was left I would keep. I’ve been amassing a collection of children’s art for a long while.

NR: How do you know which ones you want to keep? How did you know what to look for?

BB: I just grabbed everything. In my junior year of college, on a snowy night on Avenue B, me and my friends found three trash bags filled to the gills with children’s art, and we threw our bags over our shoulders like Santa Claus and went off to our apartment. When we ripped the bags open, we found that they were full of Wynton Marsalis’s kids’ art. There were hundreds of drawings – some amazing specimens, really. I spent a good portion of my year at SVA photocopying this work, painting over the photocopies. After art school, I stopped dealing with children’s art for quite a while. Then, I started working for the artist Donald Baechler – I worked for him for ten years – and while at his studio, I started going through his bookcases, and that’s where I found books by Rhoda Kellogg.

NR: Tell me about Rhoda.

BB: One of her earlier books is What Children Scribble and Why, where she goes into the world of scribbles and tries to make sense of them in a semiotic way. Her books blew me away. I became obsessed with children’s art. I spent late nights on eBay and Amazon looking up any title that had to do with children’s art, and a lot of the books I found were about using children’s art as a measure of intelligence or as a measure of trauma or setting up a curriculum from a teacher’s point of view. Rarer were catalogues from children’s art museums or ones that were nationalist: Romanian children, Russian children, American children. Rhoda’s books popped to the forefront because she seemed uninterested in head-shrinking or manipulating the data of children’s art. She was in awe of it. In a kind of Jungian way, she was interested in finding the archetypal aspects of children’s art.

NR: To what end? What sorts of conclusions does she come to?

BB: Well, one thing I would say is that, when she did this, her colleagues gave her the cold shoulder. Up to that point, it was thought that scribblings and finger paintings were essentially like making mud pies. They were nonsense, like a radio when it hits static, so it wasn’t worth studying. I just think it’s really interesting that a woman who went up against a lot of indifference from her colleagues pursued something that was seemingly absurd – it’s like a Dadaist gesture, going into mud trying to find language and coming out with mystical truths, like that we all are one family before we are nationalized. It’s an amazing feat, I think.

She went around the globe collecting kids’ art, so a lot of the art in this show is international. We have art here from Switzerland, from India, from Egypt, from Tibet. What she found was that no matter where finger painting went on across the globe, kids were essentially drawing the same stuff. In Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell compared creation myths, showing the common thread through seemingly disparate cultures. Rhoda was finding the same thing, but in children’s scribbles. She was going into this nexus of gobbledygook and nonsense, with very little support, and she winds up finding that within scribbles are repeating shapes, like the mandala or the Greek cross. What she’s also seeing bubbling up from this is the beginning of all language – the alphabet.

NR: But it’s a graphic language, as opposed to an alphabetic one, so it exists apart from a specific language or nation?

BB: Absolutely. There are certain things the body loves to do, like making a cross, or an X, or a loop-de-loop. These actions are born in the time of early childhood. What’s wild, too, about this practice is that, for the kids, it’s akin to running around on the playground, because kids are only half of the time thinking deeply about what they’re doing. It’s more about motor action and covering a surface.

NR: Is the children’s art in this show from your collection?

BB: No, it’s from hers. In one of her books, she talks about having 100,000 examples of children’s art. Then in another, she talks about having half a million. By the end of her life – she was born in 1898 and died in 1987 – she is said to have over a million. For this third show, I wanted to have a historical element, so I reached out to the Golden Gate Nursery, which she was a part of, and they told me that the collection is on the East Coast, in a storage locker in Connecticut.

NR: Incredible!

BB: I’ll tell you, it’s rough, because throughout my life I’ve been obsessed with things, and when I get obsessed I’m just a goner. So when I saw this storage locker and over a million examples of children’s art packed tightly in boxes that hadn’t seen the light of day for a couple decades, it was like when Cortez saw the City of Gold. Over the winter, I went up there about six times, and it was freezing, I would see my breath, but I would just stay in twelve-hour sessions, going through stacks, going through them like a rolodex.

And in the course of going through the storage locker, I found out a lot about Rhoda’s personal life, which was intense. I found out that she was married twice and that she had a daughter who committed suicide. And I wondered if this is the Picasso kind of thing, the neglect of the kids because the parental figure is busy doing something else – in this case, catering to kids and theories. I found out quite the opposite – it was after her daughter’s death that Rhoda embarked on her life’s work. One can’t help but imagine that maybe this trauma was the jet fuel for all of her discoveries.

She was in her mid-forties when she started all of this stuff. I also discovered that Rhoda had directed a film, which we’re showing in the other room. Even the Golden Gate Nursery didn’t know it existed. There are only two copies in the US, and we acquired the film and digitized it immediately. I also found a manuscript of a book she never published, called How One Three-Year Old Girl Taught Herself to Draw. We printed a version for the exhibition. The girl’s name is Jessica, and I found hundreds of examples of her art in the collection.

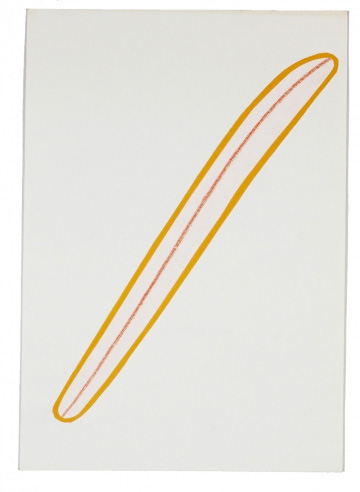

A scribble, cut out and mounted on paper, from Rhoda Kellogg’s collection.

NR: Some of your paintings are in the show, too. How did the idea to include different kinds of work – yours, the collection’s, and new children’s art – come together?

BB: In 2014, I went up to Vermont, very close to Canada, so I pretended that my e-mail didn’t work, my phone didn’t work, and all the responsibilities of New York were gone, and I started painting. I had collected all those children’s books, and whenever I saw a painting I liked I would flag it. Well, I started copying art from the books. Those paintings aren’t me riffing, they’re not me using the material in the books and going somewhere else – they’re painted as though from a model in a life-drawing class. In each one, I’m trying to get the colors right, I’m balancing the composition – every small puzzle piece.

Installation view, Brian Belott’s Dr. Kid President Jr. at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

NR: You’re looking at the original painting and painting it?

BB: And with the least amount of interpretation possible. What I found, of course, is that what’s charming about children’s art is how they barrel into a room. The Katherine Bernhardt kind of thing – hit it and quit it. There’s no looking back. It’s very straightforward. No regrets. But since I was painting these more from a devotional standpoint, they lost a bit of that energy. So I see these as failures, because when you see the originals next to them, the originals are just better.

NR: It’s like trying to forge someone’s signature, and you can’t get the flourish of the original quite right.

BB: Absolutely. It’s also a game of telephone. Not only did Rhoda pick painting X for the book, it was probably then reformatted a bit, and then through the process of printing it changes, and then through my devotional process, or forgery, it changes once again. In going through the collection, I found all the fodder that went into Rhoda’s published books – all the original artwork, all the original layouts. And since there were no computers and no photocopiers, she had to painstakingly re-create each of them and get them all on a page.

NR: How did she re-create them?

BB: She was interested in the patterns, not in the materials or the colors, so she traced everything. The books that I had been going nuts over for five, seven years – they’re all her tracings. I found piles and piles and piles of tracing paper. Even the drawings on the wallpaper here have been processed through Rhoda’s hand.

NR: She did what you did.

BB: Exactly. I couldn’t believe it. That’s something I’ve seen before, as a collector – there’s a certain point at which collecting the object is not enough. Collecting them all and putting them in a case isn’t enough. Collecting them and dancing with them in a room when no one’s watching isn’t enough. You need to digest them in another way. I’ve found a lot of collector’s guides where the collector has redrawn everything. For the collector, holding it isn’t enough. Their hand has to process the thing to feel satisfied again. That’s one of the themes running through this show. Of course, she was trying to collect scientific data. But I think she was tracing, also, to understand the subject more, because her hand was actually digesting her collection.

NR: Did she come to conclusions about development?

BB: Well, she was really obsessed with being hands-off. She felt that the teacher should be there to supply the materials and a certain amount of encouragement, meaning that if a kid makes something great, you shouldn’t go to the kid and say, “That’s amazing!” Because the kid will just repeat that. She was very particular about not interfering. She was also not interested in asking questions like, “Is that a house?” She would just say, “What is that?” And if the kid said, “It’s a tornado,” she’d ask what the tornado was doing. She would keep asking questions rather than cement or finalize anything.

NR: Do you think that way of approaching art has extensions in work by adults? If a certain approach by an artist is overly praised – whatever that means exactly – is the artist more likely to get locked in to that approach?

BB: I think it’s a difficult thing, because the academy is a double-edged sword. It’s what we have. I mean, as time passes since I was in college, I feel more and more feral, more and more back to my earlier roots. And I’m a bit cynical about the academy and what it does to artists. I think artists, a good deal of them, are private people who like to make stuff in their dark caves. If they wanted to be performers, if they wanted to be dancers, they would be that. What I mean is that a dancer is used to being looked at and sweating in front of people. A deer in headlights they’re not. They have headlights on them, and they are smiling, and they are sweating, and they are delivering. I don’t think painters are like that, so I think the academies and the market get it a little bit twisted when they expect artists to flourish in an environment where they’re being observed, where all of a sudden you’re with your class and it becomes about personalities, and how they cope with that. I do think that’s what Rhoda’s point hooks onto – different stages of development up to a master’s. I do think there’s something constricting about that predicament, and artists who are not up to that battle probably crumble or give up.

NR: What do you think about that in terms of critics and the way critics talk about an artist’s work? Can that be unproductive as well?

BB: I don’t know. The fact is that, at a certain point, you do have to deal with the real world, and if you want to be a real artist, you’re going to have to deal with criticism, and with an indifferent world. That’s also what I think is interesting about this show – children’s art is literally worthless, and the only people who value children’s art are mothers.

But it’s not realistic to erase critics. I mean, currently I’m grappling with the fact that this show was reviewed in the New York Times, and I’m furious with the way it was reviewed. It really pissed me off, but all it did was just get me more on my grind.

NR: What didn’t you like about it?

BB: I feel like the show is a church to children’s art. I don’t know how anyone could do anything but feel, like, Wow! The show, aside from being uplifting, is packed with hundreds of ideas for adult artists to steal from. So I met the reporter, and I spoke to him for twenty minutes, then he told me he was from the New York Times and I spoke to him for another twenty minutes, and then he wrote me at home, and I sent him detailed, long explanations, and then when the review came out it just seemed like he said, “It’s hard to see stuff.” Like, what? That’s what you had to say? It’s hard to see stuff? I can see stuff. Churches are supposed to be overwhelming, and that’s what I wanted to do, to make the children’s art rise up into the vaults of the ceiling, a twenty-foot ceiling, and maybe to make the adults feel dwarfed again, like a kid does. I also wanted it to feel like a tidal wave of children’s art – a natural force that won’t be stopped. It’s happening around the globe at every second, and so I wanted people to be overwhelmed by the endless permutations of this natural force. If Basquiat just sold for $130 million and this is worthless, then so is the practice, so is the teacher that teaches the course, so is the curriculum. And of course it is. You see that education is threatened under this current regime. Well, what do you think about art classes? Art classes are an endangered species. It’s absurd and sad, so I wanted to slap people with, like, “Look at the celebration of children and their imagination, it’s limitless. And you want to take this out of their curriculum? You want to take pencils and paintbrushes out of children’s hands?”

NR: You’ve done the opposite – you have classrooms of kids coming in to make work and add it to the show.

BB: The morning after the show opened, we started hosting classes, and they began with marker and crayon. Sam Moyer and Eddie Martinez were the artists standing in on that. And then from there it went to collages – I hosted those classes. Then it went to tempera painting and self-portraiture, then to printmaking, and now in the last week, we’re talking about doing a mural with a school, and we’re also talking about doing a puppetry workshop. The kids are surrounded by their own art, not by the unattainable Michelangelo or da Vinci or Rembrandt or Escher – the stuff a kid sees and thinks, “I’ll never get there.”

Since this is a church, I wanted to put in a rose window. It’s Rhoda’s mandala, and you read it from the center out. In the center are the early developmental stages and symbols that are common in children’s scribbling and finger painting. As you move outward, you see the different classifications, whether they’re boats or buildings or planes or animals, and the different aspects of the early ways we draw the human figure.

A fingerpainting from Rhoda Kellogg’s collection.

NR: It’s beautiful. How did you make it?

BB: It’s a reverse-glass painting. The original drawings are Rhoda’s, and I fitted the back with Rosco gels, so theater gels are what’s making the stained-glass effect, and it’s on a light box. I wanted a rose window to give that idea of the church, but any church also needs candles. I remember this dancing tongue of fire was supposed to be the ever-present Holy Spirit. So for me there has to be an activity, a dancing flame of activity, and that is the classroom in the gallery. Without it, the show is strictly historical. The first stuff that we put up in the classroom area are finger paintings from Rhoda’s school, which is still in operation. Everything you see here now was made during the sessions, and it’s going to culminate in an event on July 1, which will be a celebration for all the kids and their parents, and they’ll take their work home. We’ll have performances, too – I organized a jazz band of kids to play.

NR: What about Art Brut? There are obvious connections, but to what extent were you thinking about Dubuffet’s approach to his own art, which came through the prism of the untrained artist?

BB: Art Brut is definitely something I’ve obsessed over, and that’s why, when I got my job with Donald Baechler, I was really happy, because he’s an Art Brutist par excellence. He’s an Art Brut semiotician. He would collect and archive the untutored hand as it shows up in children’s books, yearbooks, hand-drawn cookbooks, telephone books from other countries, all sorts of ephemera. He’s amassed an amazing library of the untutored hand. I learned a lot about Art Brut through working for him. And that’s when I stumbled on Rhoda’s books in his collection. So the study of Art Brut has led me to this show.

I think modernism has really batted this subject around a lot. You have Paul Klee, Kandinsky, Picasso. It’s so funny, because Picasso’s work has some of the best-known quotations, yet I don’t think his stuff ever really achieves the childlike quality that Dubuffet’s does. Then you have Cy Twombly, then Basquiat, even Katherine Bernhardt – artists who are not interested in necessarily rendering more “adult” modes of representation.

I’m also interested in what I call “sound scribbles.” Playing in the gallery right now is a two-hour play list of audio that I found in junk stores and thrift stores, off cassette tapes and reel-to-reels, of kids flipping out. How do you mainline that childlike energy? I think audio is a way to flip your consciousness back to that full-steam-ahead locomotion of a children’s free-associative, postmodern way of being. High and low are getting smushed together – first they’re an animal, then they’re a volcano, then they’re making songs, then they don’t finish the song and they’re screaming, then they’re playing with their cat. I really feel like the audio is a way to shuttle you back to that mindset, especially for a crowd that has digested modernism, and may have become a bit complacent. I think about when I wake up in the morning with so much energy, or when I’m leaving a prank phone call on someone’s voicemail, or when I’m going on a vacation, the first couple days, and that bubbling-over of excitement and feeling all the responsibilities being clipped off – that’s the essence of children’s art that I’m really into. And that has to do with comedy, with being goofy, that your excitement exceeds how good you’re looking or how composed you are.

NR: Some of the works from Rhoda’s collection here look like fragments of drawings, rather than whole compositions.

BB: What we’re really seeing here is the collaboration between a child and a teacher-philosopher. As I said before, she was really hands off in the classroom, but once she dragged the samples back to her workshop, she would cut into a scribble drawing, and cut around the scribble or the action that she wanted you to pay attention to. Then she made a nimbus, an identical but slightly larger area than the sample, and placed that behind the cut-out scribble, as though to highlight or halo the sample. It’s like in magic – the magician draws a circle around themselves to put all the attention within the circle and banish whatever they don’t want outside the circle. But even though she’s a scientist collecting data, there are subtle impressions of her making artistic choices. So, say, she brings in this orangey-yellow paper nimbus underneath this orange line. Or for these blue scribbles, she adds a cerulean greenish-blue underneath, and then restores it to a rectilinear piece of paper. So you have sophisticated, subtle moves going on in one drawing. I think when you have several of these on a page, it’s so beautiful – scientific and artistic at the same time.

NR: They remind me of some of Dubuffet’s later works, where he was making tightly packed cellular shapes and filling them with tiny marks. He had come to it earlier through making doodles while he was on the telephone. And he made a series involving lithographs – hundreds of lithographs that mimicked the patterns of natural forms, and he would cut them out and use them in other works, like the way Rhoda cut out the patterns she was interested in and then placed them in a new setting. Or like the collections of objects in the exhibition. Did you put those together?

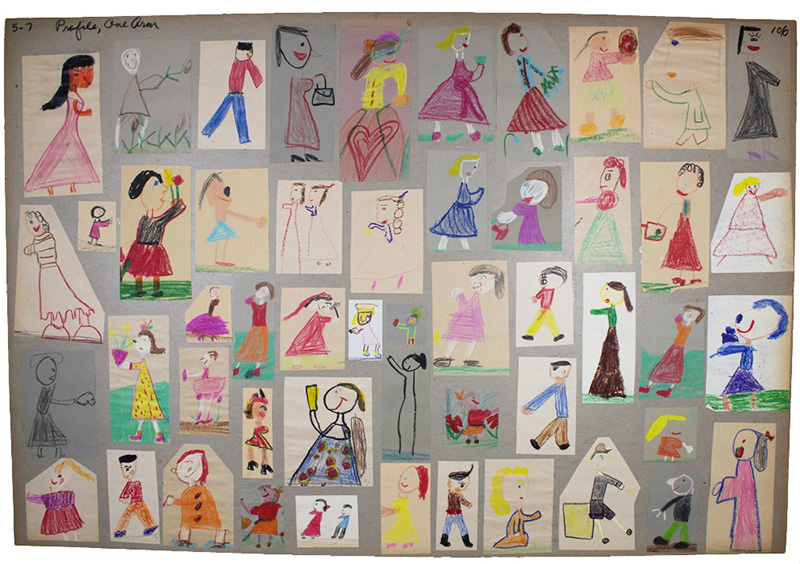

BB: No, these are Rhoda’s. It’s her classification system again, and it gets very specific. For instance, here’s a figure in profile but with one arm. She goes through thousands and thousands of examples to find every variation of the profile with one arm. I joke that it’s no wonder she lost her husband – she was too busy cutting and pasting. She was obsessed, it’s obvious. That’s what’s wild – that her obsession has resonated [with] my own.

NR: And here she’s determined that this particular form, the cross circle, results from two separate movements?

BB: Yeah. And sometimes they use their fingernail, sometimes they use the side of their hands, sometimes they use their palms, sometimes they use their elbow. She goes through every aspect that the human body could possibly use to make marks.

NR: This is Dubuffet again, but also Pollock, using the wrong end of the paintbrush, using their fingers. Have you ever thought about using these scribbles and forms and patterns as a kind of repository of mark-making in your own work?

BB: I’m very curious to see what happens when I get back to making my own work. This has really taken all of my attention. And I want the show to travel. In the best of all dreams, the collection would get a small museum or a couple rooms somewhere in San Francisco, where not only could the work be on endless display but a classroom would be there as an outreach to kids who don’t have an art curriculum in their school. This secular church should be a constant reminder of why art is so important in culture, and why it needs to be helped, dearly, and restored into curriculums. We adults should, for a moment, put a cork in it and allow the kids to be our teachers.