- Source: HYPERALLERGIC

- Author: GREGORY VOLK

- Date: OCTOBER 14, 2017

- Format: DIGITAL

The Past and Present of a Syrian-American Artist

Diana Al-Hadid is a cherished former student who is moving beyond talent into something much deeper and riskier, what Emerson called “the science of the real.”

Full disclosure: Diana Al-Hadid is a cherished former student of mine, exemplary and adventurous. As a second-year MFA candidate in sculpture when I began teaching at Virginia Commonwealth University in 2004, she sought me out, requesting to audit my Critical Issues seminar (she couldn’t officially enroll because she had too many credits). I agreed, with one caveat: She had to do the same copious amount of work as the other students — all the eclectic readings and intensive class discussions, all the comprehensive engagement. This she did, with aplomb.

We also had many studio critiques, basically every two weeks for much of one year. I witnessed at close quarters the origins and development of what is sure turning out to be a deeply compelling and strikingly idiosyncratic artistic vision, and I don’t use that word “vision” lightly.

Born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1981, Al-Hadid immigrated as a five-year-old child to Ohio, where she grew up in an Arabic-speaking Muslim family. She has thus long negotiated her way between two vastly different worlds — the West and Islam; heartland America and Syria; box store, fast food, high school football, family car Ohio, and Syria, both ancient and modern, the seat of multiple civilizations with millennia’s worth of historical remnants and architectural traces.

This negotiation is also essential for her art. I recall one studio visit when an in-process sculpture (I think it was largely made of plaster built around some scaffolding) was threatening to overwhelm her entire studio. With its slopes and indentations it suggested rolling hills — akin to parts of the Ohio landscape — but it equally suggested architecture, a brittle archaeological fragment writ large, and the weathered surfaces of ancient structures. Back then it was apparent that Al-Hadid wasn’t intent on making “successful” (an art school word that always makes me cringe) sculptures catering to the endless crits and discussions in grad school, or to the whims and fashions of the art world. Her focus was instead on creating crazily ambitious sculptures that arise from her deepest self and ultimately engage in dialogue with the world — her world — based on her very particular experience.

While at VCU — and this has certainly continued into her professional career —Al Hadid’s favored materials were not high end and splendid but Home Depot(ish) and quotidian, among them plaster, cardboard, aluminum foil, and paint. Even back then it was apparent that she had an extraordinary, almost alchemical ability to coax these bare-bones materials into startling and at times spectacular and enthralling sculptural forms. She also imbued them with acute thought, involving eclectic research.

This ability has only increased through the years. “No ideas but in things,” the great poet William Carlos Williams counsels in his poem “A Sort Of A Song,” thus fusing thought with the material world (or, as he put it in his poem, using “metaphor to reconcile the people and the stones”). This seems very close to what Al-Hadid has long been up to with her thought-filled, heavily material art, and it underpins the various works in her impressive new exhibition, Falcon’s Fortress at Marianne Boesky Gallery.

There is nothing overtly political about this exhibition, which features three decidedly eccentric (to say the least) sculptures; a set of mesmerizing wall panels made by the controlled dripping of polymer gypsum and other sundry materials, which leaves small gaps and wider openings across the surface; and willfully scruffy yet gorgeous mixed media drawings (Conté, charcoal, pastel, and acrylic) on Mylar, but it’s gratifying to witness the way the show subtly turns the tables on the frothing-at-the-mouth, profoundly ignorant, ban-the-Muslims crowd.

Al-Hadid’s inspiration for her new body of work involves two Muslim visionaries, towering figures in the Islamic world but little known in the West. One is Al-Jazari (1136-1206), the Arab polymath and mechanical engineer whose brilliant Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, chronicling (and giving instructions for) his many inventions ranging from water-pumping systems to functional candle clocks, predated Leonardo da Vinci by almost 300 years. The other is Bosnian Matrakçı Nasuh (1480-c. 1564), likewise a genius polymath — mathematician, cartographer, expert swordsman, and painter of gorgeous, intricately detailed miniature panoramas of the cities, villages, fortifications, and landscapes of the far-flung Ottoman empire, notably the cities encountered by the Ottoman army during Suleiman the Magnificent’s Safavid War of 1532-1555, involving a long march between Istanbul and what is now Baghdad, and back.

Al-Hadid’s multi-tiered “The Candle Clock of the Swordsman” (2017) features a candle-like form at the top, with molten candle wax (it’s actually gypsum) spilling down the sides; a gold falcon (tinged with green) perched, wings spread, in the middle; various small balls made of cast plastic and metal leaf and a white base with incisions, so that parts of it seem to be flowing or dripping.

It isn’t at all a faithful reproduction of one of Al-Jazari’s clocks (which kept accurate time via the decreasing weight of burning candles and the release of the small balls). It’s a riff on one of those clocks: essentially, Al-Hadid absorbed Al-Jazari’s design into her distinctive sculptural aesthetic — which is at once exquisite and unruly, graceful and rugged — and the work is a total marvel.

Diana Al-Hadid, “The Candle Clock of the Swordsman” (detail) (2017), modified polymer gypsum, fiberglass, brass, copper, steel, concrete, polyurethane foam, wood, plaster, lead, bronze, metal leaf, pigment

This is the only one of the three sculptures in the show that Al-Hadid intended to actually function, sort of. Prior to the exhibition there was a real candle at the top, which, when lit, and after it burned down for a couple of hours, actually released one of the small balls, then another.

Al-Hadid had timed the working of her clock to coincide with the August 17 total solar eclipse, thus alluding to the Islamic world’s centuries-old engagement with astronomy (this information is in the press release and available to the public). Later, candle and wax were replaced by fabricated versions.

The falcon, which is made of cast polymer gypsum and fiberglass, with additional metal, foam, and metal leaf, is riveting. It’s a version of a bird but it also functions as a powerful and mysterious totemic force. Falcons appear in the other sculptures too, and also in the wall panels, sometimes overtly, sometimes via subtle hints. It’s as if this totemic bird is traversing the different works in the exhibition, but also flashing across a vast expanse of history and time, uniting present and deep past.

A falcon appears near the bottom of “The Candle Clock in the Citadel” (2017), this time with a gold ball issuing from its chest. Way above, there is a candle and cascading gypsum “wax.” Scraps of architecture and a protective outer sheath (also hinting at architecture) are derived from Nasuh’s miniature of Aleppo’s famous citadel — an architectural and historical treasure and long the city’s central landmark—which has been gravely damaged during Syria’s civil war.

Pouring in a centrifugal whirl toward the floor, Al-Hadid’s absorbing, extraordinarily complex sculpture, while static, feels chock-full of wild motion, poised on a cusp between intricate cohesion and impending decay. Like many of Al-Hadid’s works it is also curiously mobile in time. It’s fresh and eventful, but also seems crusty and precarious, almost like an unearthed archaeological relic. It may well be the case that this sculpture, launched by an exquisite miniature made several centuries ago, responds to Aleppo right now, this renowned city punished by warfare and wantonly wrecked by the brutal Assad regime.

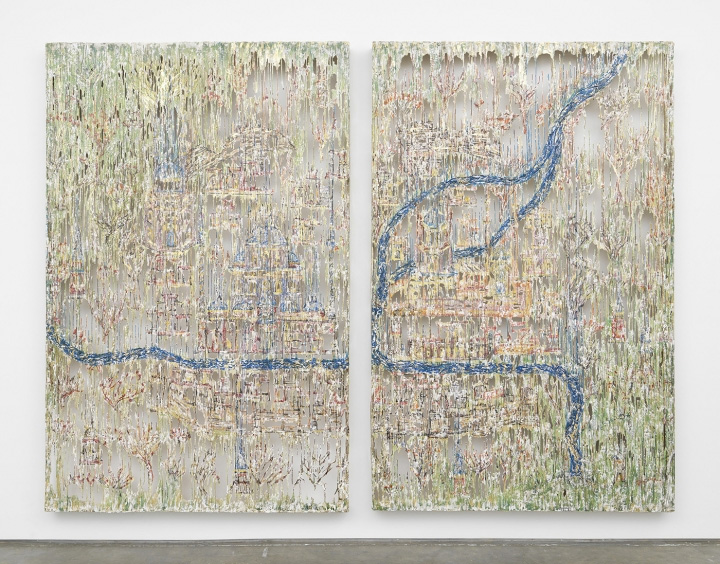

For a New York audience, the big news from this exhibition is the opportunity to see a generous selection of Al-Hadid’s remarkable wall panels, which are extremely novel variations on paintings. Instead of applying brushstrokes to canvas or wood panels, she orchestrates drips, spindly strands, and other mostly thin shapes made of various materials ( along with polymer gypsum, she has used fiberglass, steel, gold leaf, copper leaf, and pigment). These drips are the brushstrokes, so to speak, for three-dimensional “paintings” sans supports, which you look at but also through, because of their many open spaces The panels seem to almost float on the walls.

Each is based on an image (a reproduction) of one of Nasuh’s miniatures, but not obviously so. Al-Hadid magnified and reoriented the images, often inverting and rotating them, before weaving them, so to speak, into sculpted, hybrid “paintings” that are partially abstract but that also suggest architecture, architectural fragments, landscapes, and maps. Al-Hadid’s process of controlled dripping, during which she rotates the panels, allows for a gravity-defying array of activity: drips that flow up, for example, or sideways; forms that sweep across at an angle, almost like a visible wind.

In “Home Base” (2017) an irregular blue band from top to bottom conjures a river sluicing through the landscape. It’s surrounded by hints of columns and walls, houses and distant hills. Step back to take it all in and this teeming work seems full of ragged splendor. Step up close and you get enthralled by details: luminescent parts abutting subdued, earth-toned ones; little glinting bits of silver and gold; vivid, yet tiny, dabs of russet and ocher.

As with the other wall panels, this one suggests a tapestry, threadbare in parts, as well as a partially eroded fresco or mural. In the large diptych, “South East North West” (2017), blue bands again conjure rivers, while myriad accompanying shapes suggest clustered buildings and fecund vegetation. Even though huge, at 130 by 168 by 5 inches, and presumably weighty, this work, with its many openings, seems diaphanous, almost ethereal.

There is a large oval opening on the left of “The Falcon in the Mirage” (2017) and while it suggests outright damage — a hole in a painting or tapestry, say, or a blank space in an eroded fresco or mural — it equally suggests a portal providing access to some other dimension, a conduit to the remote past. It takes a while (or at least took me a while) to realize that the white, gray, and gold, seemingly abstract form at the bottom of the oval is another falcon, with attenuated vertical gypsum strips jutting from its back and head, endowing it with a sort of magical energy.

There is something very dear and touching about this bird, at once powerful and vulnerable, as it surveys a “landscape” that seems both wrecked and wondrous. Here you see how expansive Al-Hadid’s eclectic techniques really are, as they embrace world-shaping forces of cohesion and entropy, regeneration and decay. Also, while Al-Hadid’s wall panels arise from a complex engagement with Nasuh’s miniatures, and by extension with the so-called “golden age” of the Ottoman Empire, it’s likely that her strong feelings for her childhood homeland — especially at this time of utmost distress — are crucial to her new work.

Completing the exhibition are three of Al-Hadid’s drawings on Mylar. Each is a complex, all-over mesh of lines, shapes, and muted, yet still vivid, colors. Although largely abstract, these drawings contain abundant hints and traces of architecture, landscape, and figures, and while quiescent — even meditative — on one level, the more you open yourself to them the more you register how crackling and agitated they really are.

For me, the joy in being a professor is witnessing (and somehow being a part of) an obviously talented young artist’s progress, moving beyond talent into something much deeper and riskier, the kind of questing authenticity that Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his essay “The Poet” (1844), wonderfully termed, “the science of the real.” (This essay was in fact the introductory and foundational text of the seminar that Al-Hadid audited.) That’s what I experienced with Diana Al-Hadid years ago, and it is what I have experienced again, in droves, with her scintillating and deeply meaningful exhibition.

Diana Al-Hadid Falcon’s Fortress continues at Marianne Boesky Gallery (509 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through October 21.