- Source: The New York Times Style Magazine

- Author: Kirstin Valdez Quade

- Date: AUGUST 17, 2017

- Format: ONLINE AND PRINT

The Other Side of the Wall: A New Generation of Latino Art

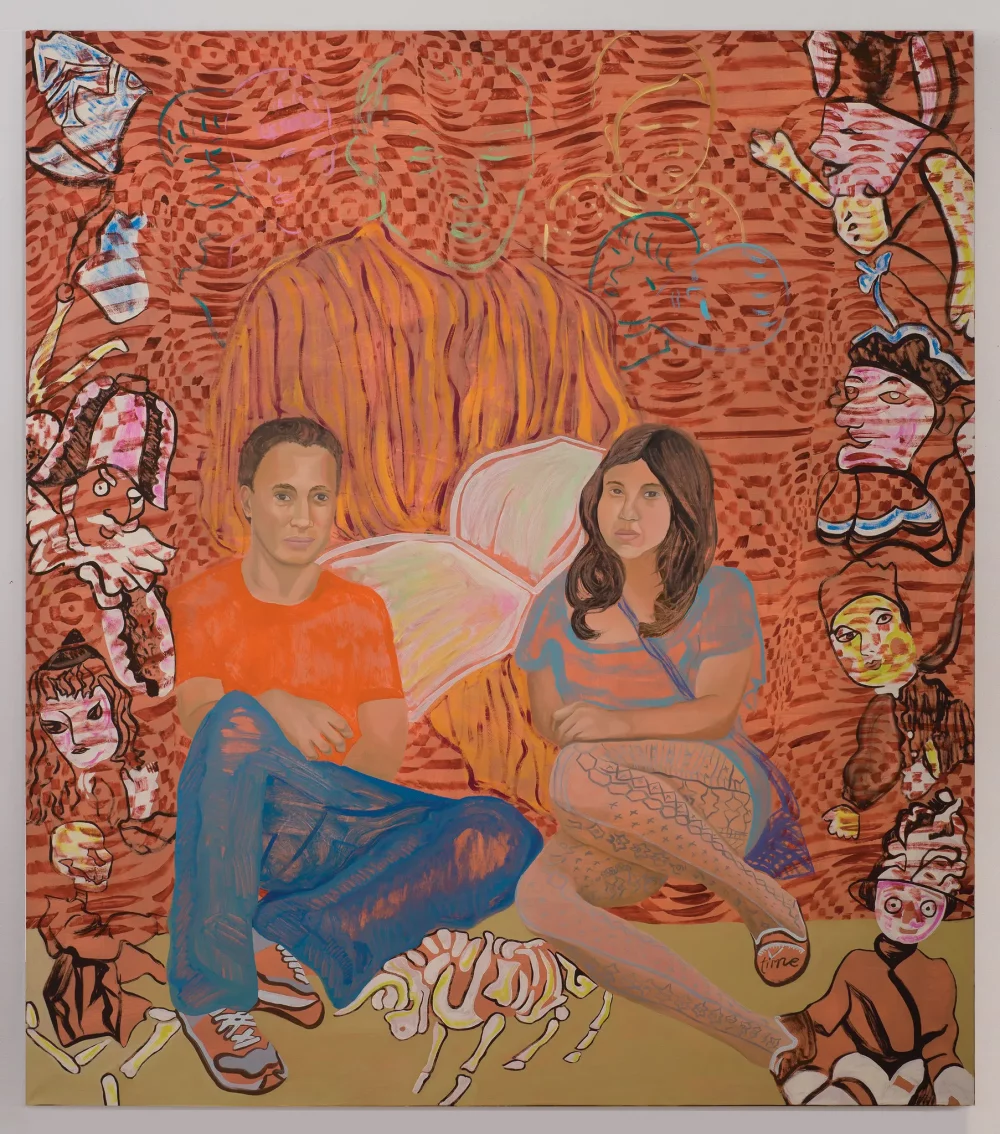

"The History Lesson," a 2017 painting by Aliza Nisenbaum, depicting Carmen and José, second-generation American citizens in Queens. Framing the painting are images from a 1950s-era Mexican coloring book.Credit...Aliza Nisenbaum, "The History Lesson," 2017, oil on linen, image courtesy the artist and Mary Mary, Glasgow

WHEN I WAS 22, living in Tucson, I visited my then-boyfriend who was staying in New York for the summer. I was a country mouse — a desert mouse, really — in awe of everything, head tipped up to see the sights.

He was living in Brooklyn, in a huge building of not-exactly-legal artists’ lofts, and on our way out one morning, we found ourselves in the newly painted elevator with a Real New York Artist. Weary and angular with lank blond hair, elegantly sheathed in black, yet still casually paint-flecked: She was exactly how I’d imagined a Real Artist.

My boyfriend pointed out the fresh graffiti scratched in the beige paint, chuckling. “They got to it already.”

“Mmm, yes,” said the Real Artist, slow and sardonic. “Those who can’t find canvas find walls.” She stretched out this last word in a way that struck me as both ludicrous and terribly sophisticated.

When she stepped out of the elevator, I burst out laughing and repeated that line incessantly — and, no doubt, annoyingly — for the next several days. Those who can’t find canvas find waaaalls.

Raúl de Nieves, who was born in Mexico, photographed in his New York studio. The artist’s intricate installations with faux stained glass and plastic beads often reference Catholic imagery. Credit: Jason Schmidt

WE HAVE BEEN TALKING about walls a lot lately. The chants at our president’s rallies (“Build a wall!” “Lock her up!”); the discussions about sanctuary cities; the argument over what counts as a wall and what is merely a fence — all this political rhetoric forces us to consider what walls keep in, what they keep out, whom they shelter, where they are permeable. And so we must consider, too, what art is hung — or scratched — upon them. These days, I think about walls in relation to a number of Latin American and Latino artists who are engaging with our current moment, and in doing so, are challenging what an art space is and who belongs in it.

Walls, of course, are sometimes manifested not as physical barriers, but as institutional ones. The Museum of Modern Art in New York staged its first exhibition devoted to Latin American artists in 1942, and since then, Latin America’s role in the development of Modernism has been acknowledged by most cultural institutions — though in many cases not significantly. Latino and Latin American art remain underrepresented in many mainstream American museums.

But this is slowly changing — MoMA’s holdings of Latin American art increased substantially after a donation last fall of works from the collection of philanthropist Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, who has collected art from the region for 40 years. Then there’s the latest installment of Pacific Standard Time, an occasional survey of art from Southern California spearheaded by the Getty Foundation. This year’s exhibition, which begins in September and is on view through January of next year, will focus entirely on Latino and Latin American art, in over 70 exhibitions and programs across Los Angeles and elsewhere in the state, offering something akin to an official acknowledgement of the Latin American diaspora’s artistic influence and legacy in the United States and the vibrancy and range of contemporary Latino art.

Any exploration of Latino art must necessarily be vast; after all, the category Latino is terrifically capacious, encompassing dozens of cultures and identities and origins and histories. Unlike Latin American art, which has historically been rigidly and reductively divided by nationality — Mexican art, Peruvian art, Cuban art — Latino art is less about a single ethnic origin than it is a shared experience. Now, decades after the first major wave of Mexican immigration to the United States before World War II, work made in the U.S. by artists of Latin American origin has come into maturity as its own genre.

What characterizes it is a sense of shared history, of shared contradictions. To be Latino is, in many cases, to have descended from both the colonizer and the colonized, to be between languages or to mourn the loss of a language. People who identify as Latino might be recent arrivals to the United States, or might have a centuries-long history with land now known as the United States. Latino culture isn’t monolithic. There isn’t a single artistic or political philosophy. And there certainly isn’t one story, one Latino identity. Primarily, however, Latino art is American art, and much like feminist art in the 1970s, or queer art in the 1980s, Latino art in 2017 says as much about the country at large as it does about any single group; the work is both predictive of and a response to the current political moment.

A still from Yoshua Okón’s video project about Oracle, Ariz., a small town that has been the site of anti-immigration protests. Okón’s work will be included in the 2017 iteration of Pacific Standard Time, a series of exhibitions that will draw connections between Latin American art and Southern California. Credit: Yoshua Okón, "Oracle," 2015, video still, 12:36 minutes, looped, courtesy of the artist and the Torrance Art Museum

ONE OF THE MOST MOVING works in the new Latino art canon is the Los Angeles-born Rafa Esparza’s “Figure Ground: Beyond the White Field,” 2017, which was exhibited at this year’s Whitney Biennal. Esparza built a gallery within a gallery, a physical wall of rough, unplastered adobe made through traditional methods from the mud and water of the Los Angeles River. The result is extraordinary: a hushed, cool, earthen sanctuary that almost feels underground. It’s an art space, but it also felt, to me, like a holy one, reminiscent of a kiva.

Esparza made the adobe blocks using methods he learned from his father, who built a home from adobe in Mexico before immigrating to the United States, and who helped the artist install the piece in the museum. The L.A. River has been a frequent site of inspiration for Esparza. In 2014, he performed with Sebastian Hernandez, an artist and Aztec dancer, under a viaduct in the working-class, largely Mexican-American neighborhood of Boyle Heights, which abuts the river.

Esparza’s Whitney piece insists on community and inclusion: It is, in fact, a gallery for other L.A.-based Latino artists who were not originally invited to participate in the official Biennial show — the adobe walls displayed, among other works, arresting photographs of steady-eyed young men by Dorian Ulises López Macías. Then there was Gala Porras-Kim’s sculpture “Reconstructed Southwest Artifact,” which incorporated a painted Native American potsherd purchased from eBay (no provenance given, “condition: used”). Porras-Kim’s art, like Esparza’s, is a kind of running commentary on erasure and appropriation and value — monetary and otherwise. Just as Esparza brings soil and river water and traditional labor into the rarefied walls of a museum, Porras-Kim examines how context changes an object’s meaning. For a show at the Hammer Museum in L.A. last year, she took obscure ethnographic objects from the collection of the Fowler Museum at U.C.L.A., all of which had been categorized as “unidentified” — including textile scraps and broken pottery — things that had effectively been deemed originless and valueless, divorced from their history and the history of those who made them. Placing these fragments on display in a contemporary art show asked the viewer to consider the forgotten lives of the people who made them, and offered a sly commentary on the very organizing principle of museums everywhere: What gets to be displayed by an institution, and why?

Also creating sanctuaries is Raúl de Nieves, who was born in Mexico and now lives in New York. In contrast to Esparza’s contained space, de Nieves’s 2016 installation “beginning & the end neither & the otherwise betwixt & between the end is the beginning & the end,” is all openness, light and extravagant color. Marvelous glittery stalagmites and figures elaborately costumed in pontifical vestments and Marie Antoinette-like wigs are arranged before a massive allegorical faux stained glass window made of plastic and tape that depicts love and sex and violence and death.

The spectacle of de Nieves’s work at once delights in and undercuts the decadence, pageantry, beauty and symbolism of the Catholic Church, royal courts — and perhaps the museum itself. A subtler response to the question of what belongs in a museum was “Salón-Sala-Salón (Classroom/Gallery/ Classroom),” created in 2017 by Chemi Rosado-Seijo, who lives in Puerto Rico. He swapped a gallery space at the Whitney with a classroom at the Lower Manhattan Arts Academy, a reprisal of a 2014 work first staged in San Juan. The gallery was a working classroom, complete with trash cans and paint-splattered tables and student art on the walls. Students came to the Whitney for their classes, and viewers were invited to the Lower Manhattan Arts Academy to view the professional art displayed in the classroom there. Here, the workspace was elevated to art, and the boundaries between student and professional, between product and process, between the child and adult worlds blurred, and were made penetrable. The very act of entering the room became a kind of border crossing.

BORDERS OF ALL KINDS have become recurring touchstones among Latino artists. Postcommodity, an art collective based in New Mexico and Arizona and made up of Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez and Kade Twist, indigenous artists with roots in Mexico and the Cherokee Nation, looks directly at the physical boundary of the U.S.-Mexico border. Their video “A Very Long Line,” 2016, documents the fence between Agua Prieta, Sonora and Douglas, Ariz. The work was filmed from a car, and we’re moving too fast to take in the whole landscape — mesquite and green-trunked palo verde, yucca and prickly pear, bleed into residential neighborhoods and telephone wires. As the camera sweeps around, we hear wind and passing vehicles, clanking as though we’re crossing over a cattle guard. Because the projection gives the sense of space beyond the gallery wall — and beyond the fence that’s being filmed — there’s simultaneously a sense of entrapment and expansiveness, of possibility and limitation.

The title evokes the very long line of the U.S.-Mexico border, of course, and the linear journey of driving that border, but also the long and tangled lineages of the people who populate the borderlands. Without ever seeing people, without ever hearing human voices, we’re reminded that the fence splits the tightly bound communities of Agua Prieta and Douglas. We’re forced to consider the arbitrary nature of borders, the ways that communities and individuals and ecosystems can become casualties of political forces.

The piece was destabilizing, but there was something remarkable about the flash of recognition I felt while viewing this work. As I watched, I was flooded with associations from my own trips to the Sonora-Arizona border. The smell of creosote and soil. Big white border-control trucks, speeding from behind, passing smoothly in a blast of hot, dusty air. Hiking on a trail scattered with traces left by people making their long journeys: cast-off clothing and crushed plastic water bottles, a stuffed dog, everything that isn’t essential and can’t be carried.

The militarization of the border and America’s shifting immigration policies are increasingly urgent themes as well. Yoshua Okón, born in Mexico, where he currently lives, and educated at U.C.L.A., has made a quasi-fictional documentary video about Oracle, Ariz., the location of the largest-ever protest against child immigrants from Central America. The video includes a re-enactment of the protest, staged by members of an organization called Arizona Border Protectors, alongside footage of nine immigrant children performing the U.S. Marines’ Hymn. (The video will screen as part of Pacific Standard Time.)

But though the experiences of Latinos are diverse, the narratives that dominate popular culture tend to be lazy: harrowing journeys across the border; undocumented criminals robbing and raping; children torn from their parents’ arms by ICE agents; drugs flooding northward. And then there are the stock characters: the wicked coyote, the ruthless trafficker, the bright-eyed abuelita with her folk wisdom and unshakable Catholicism, the hardworking and/or exploited housekeeper or fieldworker who is either taking jobs from Real Americans or doing jobs Real Americans won’t do.

These stories mask the complexity and humanity of actual people and become their own kind of wall, obscuring truth, demonizing or romanticizing entire populations. Many Latino artists have looked to the domestic space to answer such typecasting, offering a rebuke to a cliché with something specific and intimate. The L.A.-based Carmen Argote, whose work will appear at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art as part of Pacific Standard Time, makes installations using the carpeting from her childhood home in Mexico, rendering her family history in spare, minimalist sculpture. There’s also Aliza Nisenbaum, whose rich, candy-toned paintings of undocumented Mexican immigrants pay homage to the first wave of Mexican and Argentine realist painters to exhibit in the States, like David Alfaro Siqueiros or Antonio Berni, both of whom were part of MoMA’s early holdings of Latin American art, and also contend with stereotypes in their work.

Part of the power of Nisenbaum’s paintings is that they make visible people and moments that are usually overlooked. In “La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times,” 2016, a father and daughter read a newspaper against a backdrop of exuberantly painted Talavera tiles. They are undocumented, but it is their relationship that animates the picture, not their immigration or employment status. There’s a lovely ease in their postures, an intimacy in the way the father rests his hand on his daughter’s leg. The daughter stretches along the length of the couch, her hair spilling, the newspapers drifting to the floor. In the slightly skewed perspective, there’s a sense of instability, of precariousness; perhaps the couch is too narrow and the daughter will fall off. Yet in this moment are beauty and pause.

The piece is a reminder that if there is a commonality in Latino art, it’s the emphasis on community, on connections as both a source of solace and as a necessary means of change. Through witnessing one another’s stories, in all their nuance and complication, history can be rewritten, and walls, no matter how forbidding, might even be scaled.