Photo: Courtesy the artist; Anton Kern Gallery, New York; and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects / © Nicole Eisenman

First, massive congratulations to the Whitney. Even with long, flat patches of overly well-behaved work, a strange visual monotony that makes this show predictable (the prior iteration was more optically alive), generally weak painting, and collage and assemblage far too beholden to Robert Rauschenberg, this Biennial has as many as 15 standouts — which, judging by past versions, is a lot! Breakthroughs abound. Over half of the 75 participants are women, and over half are artists of color. Amen. Skeptics and cynics who say these demographics are achieved by good little humanist curators checking boxes to show how woke they are will be thrilled to learn what has always been obvious: Having an exhibition reflect the world this way makes the show better. This Biennial’s spacious installations, which unfold easily and bloom into almost solo presentations that then strike up interesting conversations with nearby work, makes it better still.

The show is also young. Of the 75 artists, almost 75 percent are under 40; 20 of them are under 33. The curators, Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, are 35 and 46, respectively. Together, they have brought to boil an idea that’s been bubbling in front of us for a long time: Subject matter is as important a formal feature of art as form itself as a primary carrier of change and newness. My wife, Roberta Smith, boils it down to “Subject matter is the new form, good and bad.” Look carefully at Carissa Rodriguez’s handsome silent film of tony interiors and sculptures by Constantin Brancusi as it morphs into a filmic Louise Lawler exploration of various rich collectors who own editions of the same Sherrie Levine–appropriated Brancusi sculpture; The Maid, as the work is titled, becomes riveting in its insinuation of cookie-cutter collector taste and what goes into maintaining this system of wealth and accumulation. Elle Pérez’s small color photograph of a person with black eyes showing a red scar on their neck spotlights someone who has just had their Adam’s apple removed in sex-reassignment surgery. And I have to say that White Noise, American Prayer Rug — a large, seemingly abstract wool-and-cotton work by Nicholas Galanin, an artist of Tlingit/Aleut and non-Native ancestry — nails the malign aberrations of what’s happening with whiteness in America as well as what all information turns into right now, as the ice near Galanin’s Alaska melts. This piece could fly over the White House. Over and over, subject matter like this melds with structure, surface, and form in ways that require very little explanation.

Yet for a Biennial with so much diversity in who is being shown, there’s an enervating lack of formal innovation, as if the curators couldn’t take those kinds of formal chances. As a result, sometimes a whole room fizzles. A number of inclusions are so generic and proper they become placeholders. Often, though, formally non-daring works breathe quiet fire and seethe. While we used to believe art history was a progression of one ism and style to the next, artists are now inhabiting the beautiful ruins of the art of the past 125 years — not to mention the glories of 50 centuries of art before that — and are making new things with old tropes. They dance on teleology’s grave, using the canon and previous art willy-nilly as material, fodder, form, information, and tools to make their own work. Call it “sustainable aesthetics.” This isn’t being done in coolly self-conscious or ironic postmodern ways, and it isn’t just pastiche that comments on or criticizes earlier art. It’s not art meant as an illustration of theory or as aesthetic gamesmanship only. It may even signal a thankful waning of the 50-year fetishization of Duchamp and Warhol (one can only hope). Artists’ free-ranging in the fabulous scrap heap of visual culture isn’t new; what’s new here is the passionate embrace of processes they’re using to embed new subjects into known genres, styles, and techniques. This points beyond the Biennial to a wider path forward and away from toeing the line of progress.

Thus all the formal echoes of Rauschenberg and the dematerializing of the art object of post-minimalist sculpture; Jessica Stockholder and Cady Noland’s notions of object-based installation; and numerous references to Pictures artists like Gretchen Bender, Sherrie Levine, and Cindy Sherman. There are even a couple of archaic tool-makers to push the clock all the way back. Video and film follow closely in either classic documentary style or the fictive tropes of Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno, Laura Poitras, Steve McQueen, and many others. When the art here works, it isn’t 95 percent reliant on obscurant wall labels. It’s enough that I left this Biennial hopeful about seeing new ideas of the poetic and subjective.

But here’s a caveat: Almost everything in this show is incredibly sincere, felt, sympathetic, and empathetic and tries to illuminate important things.

The organizers place a kind of political and physical governor on the show. Nothing here will offend. Political bona fides are all in order. This makes the show feel a little locked in, careful, and polite, as though the curators had an idea of what they were looking for and then went and found it. Happily, older artists like Diane Simpson, 84; Nicole Eisenman, 54; Simone Leigh, 52; and Wangechi Mutu, 46 — all makers of powerful, almost ancient or ritualistic figurative forms fashioned from clay, wood, straw, and other materials — are given pride of place and preside over the show like elders.*

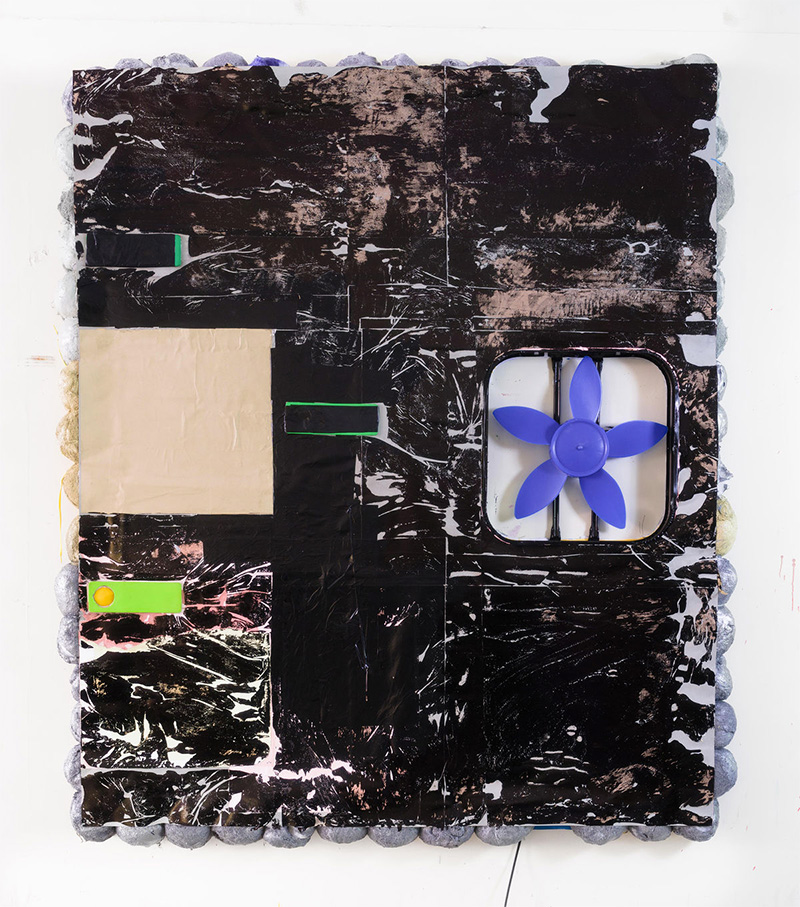

The earnestness does have upside, though. Nearly everything here is conspicuously handmade, pieced together with wire and tape. Humble materials predominate (meshes, fabric, beads, etc.), and layered busywork is everywhere, which means the two genuine so-called outsiders really fit in: Marlon Mullen, with his blazing paintings of Art in America covers, and Joe Minter, 76, a maker of twisted-metal sculptures and the builder in Birmingham, Alabama, of the giant African Village in America. The whole show is a hive of handsy art, the handsy Biennial. There’s a real sense of the artist’s studio throughout. Additionally, nothing here is overproduced or shiny or makes a spectacle of itself. There are none of the visual pows of the previous Biennial’s Samara Golden, Rafa Esparza, Jessi Reaves, Anicka Yi, Pope.L, or Raúl de Nieves.

Well, except for one: The closest thing to a showstopper is Eisenman’s huge outdoor sculpture of a fantastical Hieronymous Boschian procession of oversize Fellini-esque figures, including a severed blinded head with eye piercings and a farting man pulled along on a cart. It’s all the chaos of Trumpism and the End of the American Empire. (It deserves a permanent public home. Maybe Central Park?)

All the photography is strong. This seems to come almost out of nowhere, as it hasn’t been the case for a while at the Biennial. Memorable is the documenting of the black and white American working class by Curran Hatleberg, which feels connected to previous Biennial standouts Alec Soth, Zoe Strauss, and Oto Gillen and almost seems Pulitzer-worthy. Pérez’s pictures of their gender surgery remind us that Catherine Opie’s strongest work initially appeared in the storied 1993 Biennial. John Edmonds employs staged photographs of black figures posed with African objects to take back this purloined field of the modernist fetishizing of black bodies.Heji Shin does the same with mother-and-child photos, giving us close-ups of babys’ heads crowning in the act of birth. Lucas Blalock’s photo mash-ups remain as knotty as ever, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya makes sexually aware pictures that project quietly complicated agency. Todd Gray’s collaged pictures remind one of 1980s artists like Alan Belcher, Anne Doran, and Sarah Charlesworth but with a personal urgency that seems to come from the artist having once been Michael Jackson’s official photographer; little snippets of these pictures are included here.

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York and Rome

The biggest overall weakness of this Biennial is painting. While I love Brian Belott’s work, and Janiva Ellis and Pat Phillips are okay, the rest is generic. This is a big missed opportunity that sadly neglects the extraordinary liveliness now afoot in the medium. What is it about curators these days that makes them unsure of or oddly averse to or put off by painting’s much older, more chemical-based psychic alchemies? This academic prejudice needs to end.

As with any group show like this, the best strategy is to sort out what you don’t like and focus on what might be here for you. Right off the fifth-floor elevator, the show touts its credentials in the form of Kota Ezawa’s lyrical animated National Anthem, assembled by rephotographing his watercolors of NFL footage of Colin Kaepernick kneeling in mournful observation of the national anthem. Seeing these images stripped of all the bile projected on Kaepernick (he never played again) and with only the soft strains of the anthem as witness, viewers are left with how extraordinarily brave this moment was.

More generic still but just as riveting is Alexandra Bell’s 20-part Friday, April 28, 1989. Using an almost identical strategy to Charlesworth’s Movie-Television-News-History, June 21, 1979, Bell redacts parts of pages from New York Daily News coverage of the five Central Park “rapists,” all young men of color who were found guilty of brutally raping and murdering a white woman, imprisoned, and then exonerated of the crime and released. See the grotesques of white America describing the boys as a “wolf pack” and “animals” who should be “put to death.” Donald Trump’s full-page ad placed in all New York newspapers on May 1, 1989, is here too. It called on the courts to revise the law so these minors could be put to death. Trump said, “I hate these people … maybe hate is what we need if we’re gonna get something done.” All of this has been coming for a long time, and now it’s here.

Photo: Courtesy the artist and White Space, Beijing

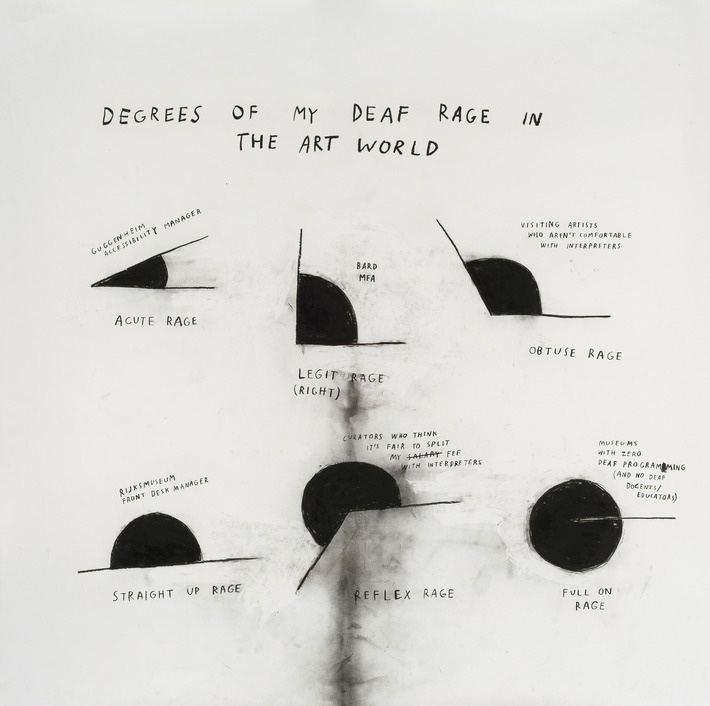

If you want another kind of blasting indictment, look no further than Christine Sun Kim’s affecting six-part exploration of her own “deaf rage.” Formally, the work resembles large-scale Robert Smithson, Mel Bochner, or Richard Serra charcoal drawings, but Kim uses her graphs and words to record degrees of her fury — from “acute rage” to “legit rage” to “full on rage” — at there being no interpreters at meetings and fake interpreters on TV, at her family not learning sign language, at fast-food cashiers, at airplane movies without captions, at Uber drivers’ calling rather than texting, and so much more that your heart will break. It makes you want a requirement forcing all public schools to teach students at least 150 words of sign language.

A shamanic force is put out by a number of artists, among them Tiona Nekkia McClodden with her intense multimedia arrangement of cases with talismanlike tools made from a tree she cut down and videos of the artist at work at forges. She’s on some sort of mission.

If you want to be transported to another dimension, behold Laura Ortman’s mesmerizing six-minute video of her violin performance in the New Mexico woods with appearances by the dancer Jock Soto. Nearby, be held in suspension by Ellie Ga’s slideshowlike presentation tracking tens of millions of objects adrift in our oceans. At first, I thought Brendan Fernandes’s minimalistic black jungle gym with dancers moving about it would be just generic modern dance until two of the dancers locked eyes with me and I was caught in some sort of parasexualized movement enacted on various S&M-like devices. Meanwhile, Daniel Lind-Ramos fashions large sculptural altars and spirit beings from bamboo, palm branches, burlap, and much more to perhaps watch over his destroyed native Puerto Rico. Ilana Harris-Babou’s three-part delving into the insidious hidden colonialisms of Restoration Hardware should bring you full circle to Kim’s incredulity. And Josh Kline only underscores this with his photographs of things like the U.S. Capitol, the flag, and the Twitter insignia encased in frames with water forever streaming in. All these are very subtle blast furnaces of indictment.

The culminating point and metaphorical backdrop of the whole show is the Forensic Architecture collective’s devastating video incrimination of Warren B. Kanders, the Whitney’s own vice-chairman and the owner of Defense Technology — a huge company that manufactures combat direction systems, chemical munitions, open-tip bullets, and tear gas (the last of which was fired at immigrants crossing the California border at Tijuana on November 25, 2018). Keep in mind that some of these chemical weapons are banned by international treaties for use during wartime but are generally used against a country’s own citizens for “crowd control.” Sick yet?

Many voices have publicly called for Kanders to resign, including 95 Whitney staff members, scores of Biennial artists, and many more academics — these last are often associated with or employed by the same wealthy institutions funded by Kanders and his ilk. It’s time to think about toxic philanthropy and how many of our beloved institutions are supported by fortunes like these. After all, you need look only at the Museum of Modern Art’s board to find it filled with corporate raiders, billionaires, a stock big shot whom the U.S. government found guilty of insider trading and fined $1.8 billion, a Sotheby’s senior vice-president (hello, conflict of interest), another investor guilty of selling more than $600 million in stock before the company went bankrupt, a real-estate titan who has continually sold the museum short on building deals, and others who extract fortunes from fossil fuels, oil and gas fields, pharmaceuticals, gentrifying real-estate developers, and investment and wealth-management firms, mutual funds, and hedge funds (including Lehman Brothers) that led directly to the worldwide financial collapse of 2008. Back then, I used to recoil at the sight of a former MoMA curator regularly shepherding Rupert Murdoch’s then-wife to glamorous museum events. Many museums are this deep in the morally corrupt philanthropic mud.

Before I watched Forensic Architecture’s video, I felt that a systemic cross-institutional conversation was essential and that focusing on Kanders might even be a distraction from that conversation. But the video changed all that for me. Co-directed by Laura Poitras and flatly narrated by David Byrne, this 11-minute collaborative work of artists, filmmakers, and data analysts deploys maps, diagrams, digital animation, simple effects, found footage, and the examination of 5,000 images of worldwide protests identifying numerous instances in which Safariland tear gas was deployed. Titled Triple Chaser after the three-chambered canisters that deliver the gas and allow for an extended “approximate burn time of 20 to 30 seconds,” the video effectively skewers Kanders and his Safariland company as being implicated in the killing and maiming devices used in Turkey, where over 130,000 canisters were fired into crowds, and in Gaza, where 154 Palestinian protesters were killed, including 34 children.

The previous Biennial initiated an important conversation over a painting of Emmett Till that ended with the art world being much better for it. It’s time to have this conversation about Kanders. In public. I walked into that darkened screening room thinking that calling for scalps wasn’t an answer. I left thinking, This guy has to fucking resign. Now! Think of Kanders like a Harvey Weinstein: He’s just one of very many offensive philanthropists; get rid of him and the rest might start to fall. It’s true that if scores of trustees are required to meet agreed-on institutional philanthropic regulations, then museum programs, staff, restoration, and upkeep will be affected across the board. Yet look at the moral costs of giving all this an ethical pass. Perhaps Kanders’s exit might trigger all institutions to draw up guidelines. And if you’re still not sure how deluded some of these billionaires can be, consider Kanders’s quote shown at the beginning of the film: “While my company and the museum have distinct missions, both are important contributors to our society.” Loss of millions notwithstanding, this is a train museums should want to get off of.

Props to the Whitney for showcasing this work, which is sure to come down on them like a ton of bricks. (The museum was completely aware of and endorses the inclusion.) For the second Biennial in a row, the Whitney is showing us that museums are places to have difficult conversations in an offensive world and to raise issues that aren’t polite or easy. My profound hope is that the rest of the artists in this important show aren’t eclipsed again by the focus on one object and one issue. See this Biennial and give it time, the same kind of careful time that seems to have gone into the work in it, its generous installation, and the telling aesthetics within the show. See change happening. Then help make it happen.

*This review has been corrected to show that Wangechi Mutu is 46, not 56, and Diane Simpson is 84, not 88.