- Source: HYPERALLERGIC

- Author: Angelica Aboulhosn

- Date: JANUARY 23, 2024

- Format: DIGITAL

The Divine Dissatisfaction of Music

Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly’s Musical Thinking at the Smithsonian American Art Museum is alive with pathos.

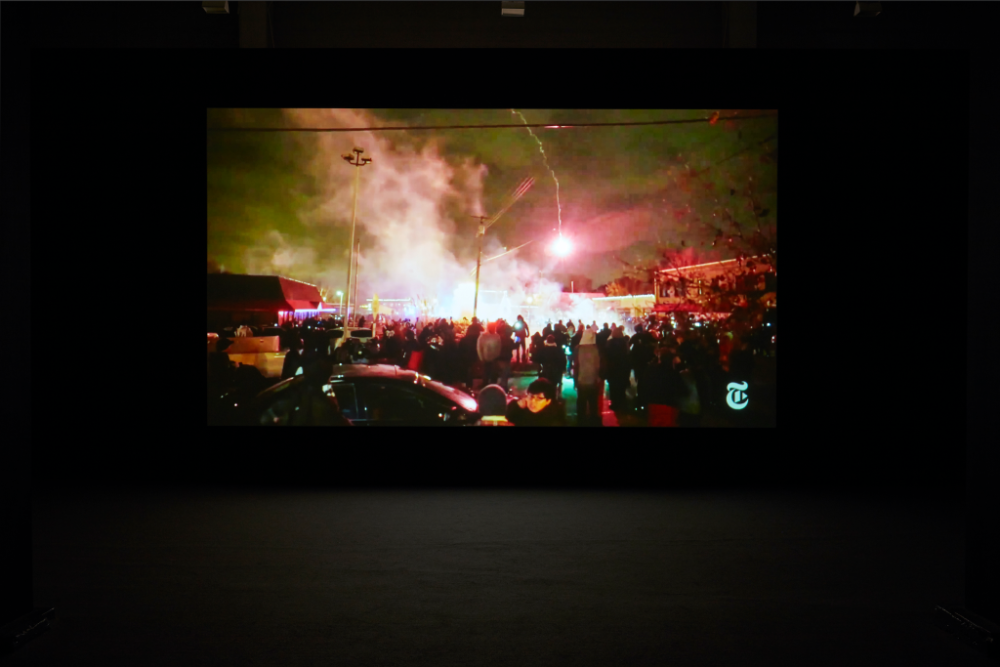

Simone Leigh and Liz Magic Laser, "Breakdown" (2011), single-channel digital video, color, sound (photo Angelica Aboulhosn/Hyperallergic)

WASHINGTON, DC — The courtyard of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC, is deceptively quiet. Even when teeming with people, the expansive room never overwhelms. In it, noise dissipates, echoing then falling away. On a recent winter night, the courtyard swelled with the sounds of wind chimes and bird calls, the lulling of conversation that begins and trails off.

Dancers clad in pearl and slate gray swayed, branchlike, to the undulating music. The performance, entitled “Like a Phantom Near or Far (An Occasional Figure Moving),” wove through the galleries as the dancers crawled downstairs, perched behind balconies, and lost themselves in dervish-like spirals on the third floor’s azure-blue and russet tiles.

Conceived by Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly, the performance accompanied the exhibition Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies. The show opens with “When the Spirits Moved Them, They Moved” (2019), an effusive work by filmmaker Ghani and choreographer Kelly. Shot in a Shaker community in Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, it follows a troupe of dancers, some donning wine reds, others in crisp whites, as they file into a sun-drenched room, where they stretch and balance, interweaving, tendril-like, with every move.

Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly, “When the Spirits Moved Them, They Moved” (2019), three-channel video, color, sound; 23:36 minutes (photo Angelica Aboulhosn/Hyperallergic)

Drawing from 19th-century Shaker diaries, whose first-person accounts are adapted in the accompanying wall text, the performance revels in the “freedom and simplicity” of the community’s gatherings, as the prose reads, where “a beautiful stillness pervaded.” It’s on that lilting note that Musical Thinking begins.

The rhythm picks up with Simone Leigh’s “Cupboard VIII” (2018), a towering stoneware figure atop a raffia-leaf skirt. Set against a canary-yellow wall, the gargantuan work anchors the show, its arms outstretched as if beseeching the viewer. But the figure’s intentions are elusive, its head a bulbous jug.

Nearby, in a darkened room, “Breakdown” (2011) plays on loop. In the nine-minute film, by Leigh and Liz Magic Laser, mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran wilts and bellows, her song an ode to female hysteria based on scenes from popular media. Drawing from Amiri Baraka’s 1964 play Dutchman, a fiery take on the Adam and Eve story, Breakdown is at times disturbing. Like the characters in the nervy Dutchman, Moran is erratic, her every twist and turn unpredictable. “I’ve been performing all my life,” she laments, “because I’ve always done it.” She shrieks and stammers, stops and laughs. To witness her vocal and bodily ebb and flow feels wrong, improper.

Martine Gutierrez, “Clubbing” (2012), HD video, color, sound, 3:06 minutes (photo Albert Ting)

Martine Gutierrez’s “Clubbing” (2012) is a fitting reprieve. A room bedecked in silver streamers sets the stage for the lighthearted short film, in which men and women in metallics and sequins — all played by Gutierrez — twist and turn to the buoyant music. “It’s one of my favorite things,” Gutierrez remarked in a 2022 interview, “to watch people watch me.” This voyeurism runs to extremes in “Clubbing,” where viewers are invited to dance on a haptic stage, to see and be seen. On a visit to the exhibition, I noticed a group of young women dancing alongside the film. Some laughed to themselves, but their dance seemed tenuous, as if they might be found out.

In his film “Love is the Message, The Message is Death” (2016), artist Arthur Jafa finds a world cracked open, seething at the edges. Images of Martin Luther King Jr. are interspersed with those of Black demonstrators, some dragged from their seats at a lunch counter. The chilling scenes reverberate through the exhibition, most poignantly in the accompanying work, “APEX GRID” (2018), the artist’s painstaking assemblage of photographs, album covers, and drawings — the sparkling fragments of a life laid bare. From an early age, Jafa collected clippings, like those in the kaleidoscopic grid, filling notebooks and binders with pictures of Black musicians and African-inspired dress. One of the artist’s guiding principles, as he noted in a 1998 essay, is articulating the “sheer tonality in Black song.” He wanted his work to move people in the same way a performer can: “I’m not talking about the lyrics that Aretha Franklin sang. I’m talking about how she sang them.” “Love is the Message” has that kind of gravitas: It awakens something real, visceral, in the viewer, and once seen it is hard to forget.

Cauleen Smith, “Pilgrim” (2017), digital video, color, sound, 7:41 minutes (photo Angelica Aboulhosn/Hyperallergic)

Musical Thinking ends with two films, “Pilgrim” (2017) and “Sojourner” (2018), both by Cauleen Smith. Effervescent images of oak leaves and orange-tinged meadows draw parallels between composer and musician Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda and the 19th-century Black Shaker Rebecca Cox Jackson. Smith was drawn to Coltrane’s writing about “celestial instruments,” which can be played, Coltrane asserted, “without the use of hands or without physical contact whatsoever.” Jackson, likewise, recounted visions in which she left her body and soared through the air, seeing the world anew. Mounted on walls of Smith’s gleaming, iridescent prints, the works have an otherworldliness about them, like a waking dream.

For me, the show recalls a chance meeting of choreographers Agnes de Mille and Martha Graham, in 1943. De Mille’s staging of Oklahoma! had just opened and was a “flamboyant success,” as she remembered years later. Still, she felt a gnawing despair. De Mille confided in Graham, who told her, without irony, that there is no satisfaction in art: “There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than others.”

The artists in Musical Thinking have that divine dissatisfaction about them. Nothing is settled, or tidy. The result is gripping and pointed, shrill and exuberant. If the aim of great art is to awaken something in the viewer, this show is a knockout.

Simone Leigh, “Cupboard VIII” (2018) (photo Angelica Aboulhosn/Hyperallergic)

Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly, “Like a Phantom Near or Far (An Occasional Figure Moving)” (2024), performance at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (photo Angelica Aboulhosn/Hyperallergic)

Installation by Cauleen Smith in Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (photo Albert Ting)

Arthur Jafa, “Love is the Message, The Message is Death” (2016), single-channel high-definition digital video, color, sound, 07:25 minutes; Smithsonian American Art Museum (© 2016, Arthur Jafa, image courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York / Rome)

Raven Chacon, “Report” (2001/2015), single channel video, color, sound, and printed score shown on music stand, Component A: 03:48 minutes, Component B: 8 1⁄2 x 11 inches; Smithsonian American Art Museum (© 2015 Raven Chacon, composition © 2001 Raven Chacon)

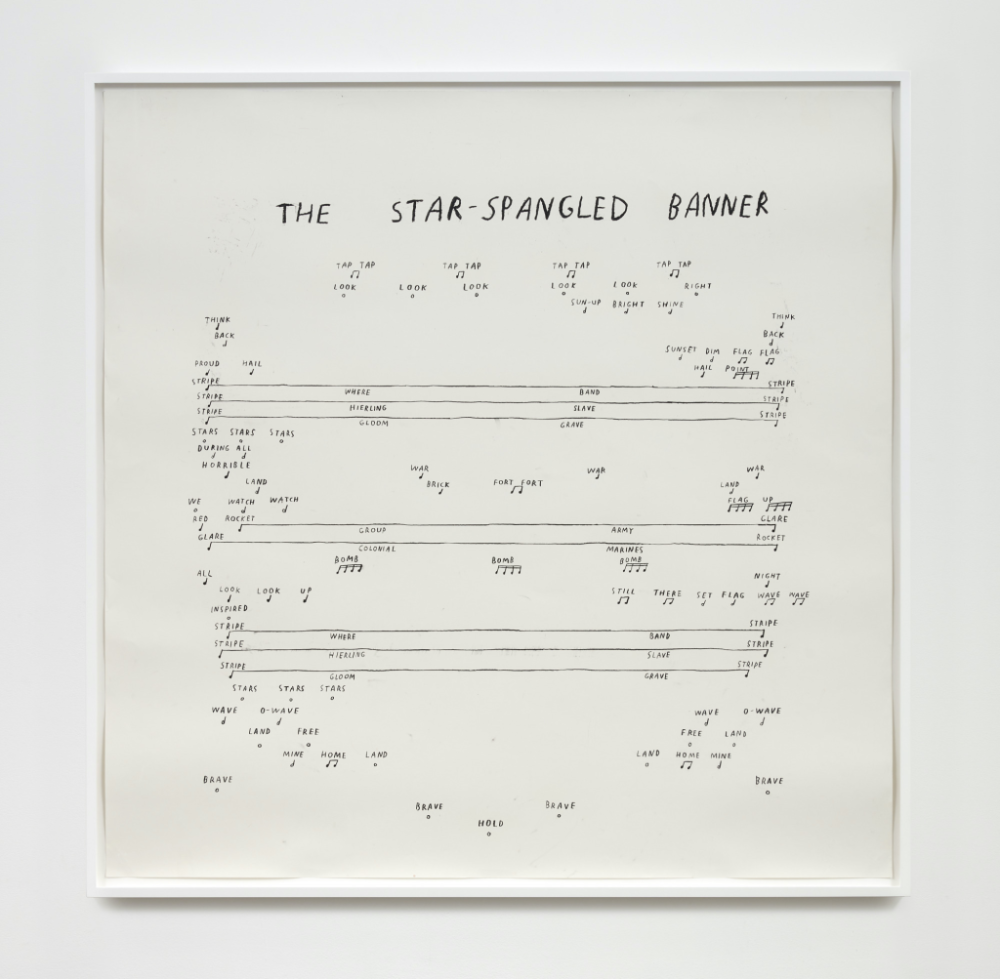

Christine Sun Kim, “The Star-Spangled Banner (Third Verse)” (2020), charcoal on paper, overall: 58 1/4 x 58 1/4 inches, frame: 60 3/4 x 60 3/4 inches; Smithsonian American Art Museum (© 2020, Christine Sun Kim, courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles)

Installation by ADÁL in Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (photo Albert Ting)

Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies continues at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (8th and G Streets, Northwest, Washington, DC) through January 28. The exhibition was organized by Saisha Grayson, curator of time-based media at the SAAM, with support from Anne Hyland, curatorial assistant.