- Source: INTERVIEW MAGAZINE

- Author: RACHEL SMALL

- Date: OCTOBER 16, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

THE CIRCULARITY OF JACOLBY SATTERWHITE, A 3D ARTIST WITH A 360 POINT OF VIEW

The cover of Satterwhite’s Love Will Find a Way Home. Photo by Wolfgang Tillmans.

In the latest video opus of the artist Jacolby Satterwhite, titled Birds in Paradise, sequence after animated sequence delivers a tapestry of fantastical images that, like puzzle pieces, coalesce into a hypnotically intricate yet fully harmonious whole. Take, for instance, one of the main characters in the second installment of the five-part series: a naked, tattooed cowboy soaring above a Roman colosseum on a winged horse-disco ball hybrid, projecting from its head a montage of Satterwhite being baptized in the ocean by a Nigerian mermaid.

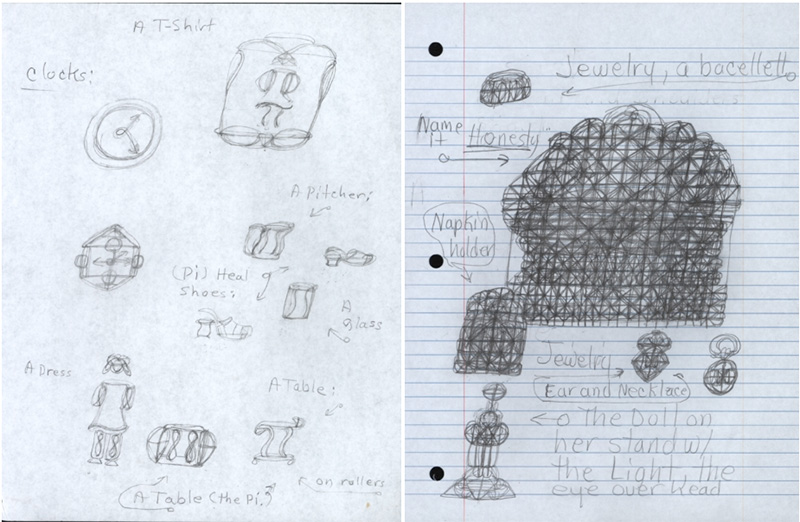

To be sure, rarely a moment in Birds in Paradise goes by without at least one gyrating figure in the frame—though much more often, undulating bodies will surface in multitudes, together carrying out elaborate choreographies across neon-tinged landscapes. All the while, the cumulative waves of movement expand and contract to the electronic beat of songs from Love Will Find a Way Home, an original album Satterwhite produced with Teengirl Fantasy’s Nick Weiss between 2015 and 2018. In the past, Satterwhite has made ample use of drawings created by his late mentally ill mother, Patricia, as part of his aesthetic language; now, for the first time in his work, Love Will Find a Way Home directly incorporates snippets from the hundreds of cappella vocals his mother recorded in the 1990s. After premiering at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia earlier this fall, Birds in Paradise debuted in New York this month as the focal point of You’re at Home, a sprawling solo presentation at Pioneer Works in Red Hook, Brooklyn that features, among other new work, 2017’s Domestika, Satterwhite’s first foray into virtual reality. One gallery is devoted exclusively to showcasing lyrics handwritten by his mother, as well as a number of her sketches depicting never-realized inventions to sell on shopping channels like QVC. Additionally, a concert stage built on-site for the exhibition will accommodate a series of performances, including live renditions of songs from Love Will Find a Way Home for the 2019 Performa Biennial this November.

Ahead of the Pioneer Works opening, we visited Satterwhite at his Bed-Stuy apartment, where we found him in the midst of putting the finishing touches on parodic faux-tabloid covers for a wall display installation of sculptural “magazine racks.” Though feverishly multitasking, he nevertheless helped us unfurl the manifold visual and conceptual layers entwined within Birds in Paradise.

Installation view, You’re at Home: Jacolby Satterwhite. Pioneer Works, New York, October 4-November 24, 2019. Photo by Dan Bradica.

RACHEL SMALL: The last time we spoke was in 2014.

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE: When we did that interview, I was making C-prints. That was basically the genesis for the project that I’ve finally finished for the most part, which is showing at Fabric Museum and Pioneer Works. It’s a feature-length animation series called Birds in Paradise. It’s a sequel to the conceptual thread that I was dealing with in Reifying Desire [2012-2014], except this is focused on music. My mom not only made thousands of drawings, she made hundreds of a cappella recordings. She would imitate songwriting structures from Top 40 hits and add folk and gospel influences.

There were these tape recordings that she would make in the mental institution and at home. When I was a kid, I was embarrassed by it. But as an adult, after grad school, I was like, “Woah, these are poignant and interesting.” They kind of remind me of Gertrude Stein or Emily Dickinson—isolated women—making these poignant lyrics that I felt needed to be repurposed somehow.

Originally, when I began Reifying Desire, I was trying to make the music a part of it, but I just didn’t have the skill set. When I got a residency at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art [starting in 2015], they commissioned me to make the album. I hooked up with Nick Weiss from Teen Girl Fantasy. He and I became best friends who shared the studio eight hours a day for two years, producing the record. Simultaneously, I always said I wanted the record to be a virtual reality album. I was thinking, “What’s the way to defy what streaming is?” A virtual reality album brings the object back to the experience in a certain way; it feels sculptural.

So, I was producing Domestika and the Birds in Paradise series. Birds in Paradise going to be playing at Pioneer Works and at Fabric Museum. Domestika is the virtual reality piece that I’m showing at both exhibitions. The music [in Birds in Paradise and Domestika] is from the album. Pioneer Works helped us mix and master and produce the album as a vinyl record. It has a 30-page book and it’s going to be streaming on all these services. Wolfgang Tillmans did the cover. It was shot at Spectrum, the nightlife space that Gage the Boone started that closed [in early 2019]. It was a place where we would all collectively go as artists. It felt like a spiritual think-hub among creative minds who were troubled. I felt a great deal of growth happen with my experiences related to that space.

SMALL: Can you say more about that?

SATTERWHITE: It was a safe queer space where I could just dissolve—in my case, to reanimate myself. It was around the time my mother passed away in 2016. It was just a personal safe space that I wanted to archive and preserve in my own work, for myself.

[A video set to a musical track starts to play on Satterwhite’s computer.]

This is the second chapter, which is called “Birds in Paradise.” It’s the result of my collaboration with Solange Knowles. I felt like her and I were both thinking on this Saturn return kind of wave, where it was more about being around 32 and reconciling things from the past in order to transition into a full adult. Circularity was the theme. She was talking about black rodeos in her work, so I started thinking about architectural spaces that express a certain kind of circularity and 360º point of view. This video plays on circularity and the rituals. There’s the disco ball spinning, the crop circles, the colosseums. There are also performance rituals that happen later in this video, which are done in these churches. I’m being shrouded by this other black man, and it’s like he’s orbiting my body. There are other references to Yorùbá Gẹlẹdẹ masquerade culture, like the Yorùbá folklore of the Mami Wata on this channel. She’s coming to bathe me and renew me and bring me back out.

The film does these harsh clashes of Western tropes and folklore and mixes it with African folklore to destabilize what meaning is. There is a part where I’m being hung upside-down and shrouded—it looks like a Klan meeting or some hate crime, if you’re in America watching it. But really, I was citing a ritual in Africa where they shroud you to renew you. It’s about the double entendre of perception. There’s a lot like that going on.

SMALL: What would you say is the key motif of Birds in Paradise?

SATTERWHITE: The circularity, the 360 degrees. It starts off with a baptism and it’s about being reborn and re-centering yourself, finding home again. My mother had these songs written in the ’90s that are on the album [for the Pioneer Works show]: “Love Will Find a Way Home,” “You’re at Home.” Home is such a major theme in my work as well. It’s uncanny how she and I came together like that because my project is the exact idea—but I was doing it on my own, for 10 years technically. It’s crazy.

Drawings by Patricia Satterwhite.

SMALL: What are some examples of African rituals juxtaposed with Western rituals?

SATTERWHITE: A rodeo inside a Roman colosseum next to a baptism inside of the ocean from a Nigerian mermaid. In some parts, there’s a figure inside of a rotunda church and he’s getting shrouded by this black man with black roses. While that’s happening, you’re watching the cowboy make a circular motion around the Roman colosseum. It’s like a wordplay with visual history.

SMALL: I feel like your work also looks more advanced on a technological level compared to a few years ago.

SATTERWHITE: I’ve grown, definitely. That’s the point of me having a sculpture show [at Fabric Museum]—I can’t stay in the same place. I have a lexicon that I work with, but I’m building that as well. I’m not stuck with my mother in my work; she’s just a part of the language sometimes. She’s a part of my trauma. She’s a part of the way I view the world. I was like Grey Gardens, trapped in a house for almost 18 years, around a specific kind of way of living in the world. Of course, I’m going to have tics and be reactionary to it. It’s a real thing that happened, but it’s not about her. She’s just a medium for me to connect with the present. Sometimes I’m connected to the present alone, without her in the work.

I look at Bruce Nauman, and I see him circle back to things, like contrappostos. I wrote about his [2018-19 retrospective] for Artforum. I talk about him in a way I’m thinking about my own kind of way: dealing with the body as a personal mythology and the body as a modernist measurement tool, like measuring your own body as a medium.

SMALL: In the broader arc of your work, what would you say are the biggest developments on display throughout Birds in Paradise and the other videos on view at Pioneer Works?

“Room for Doubt,” 2019. In collaboration with the Fabric Museum of Philadelphia.

SATTERWHITE: I think technically I’ve played with depth of field and light, and certain formalisms in my palette are more applied to the mood that I wanted to achieve in the project. In a way, the work has more of an emotional spirit because I understand how to use the tools enough to convey a lot more than I was able to before. It has more jazz. I’ve learned to be more lyrical and free. I learned to not constrict it to the video, to the 3-D animation, to the processes in the 3-D animation. I feel like I’m less of a tech artist now—I’ve revived some of my artistry.

SMALL: Your show at the Fabric Museum—which is also your first-ever museum solo show—includes slightly larger-than-life but otherwise naturalistic figurative sculptures, including four male statues comprising “Room for Doubt” [2019] that have screens in their abdomens displaying video documentation of a live performance you did. Incorporating large-scale sculptures in this manner marks a new direction in the broader arc of your practice. Can you tell me more about this piece specifically, and in general how you arrived at this new concept?

SATTERWHITE: It’s based on Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas [1601-2]. Doubting Thomas is the ultimate allegory about skepticism. I wanted to deal with the skeptic as a personal narrative and reaction. I’ve been speaking about curiosity as an infection: You have to lance the boil to figure out what the meaning is. I’ve appropriated this piece in different mediums since I was a teenager. The allegory of Doubting Thomas is believed by some to be something to get people to believe in ritual as a way to concretize faith.

Being a cancer survivor and playing games in the hospital with chemotherapy for two years when I was 12 and 13 … I was supposed to die. When I came out and I was able to continue making things, naturally there was a skepticism around my mortality. I’ve feverishly produced art objects since I was an adolescent in order to prove that I’m still here. It’s like leaving behind big sculptures and animations is a mortality defiance stand. I think that’s what this piece is reactionary to, and why I keep making it.

SMALL: It’s like you’re surprises at your ongoing existence—or also wanting to prove it to yourself.

SATTERWHITE: Mmhm.

SMALL: Overall, what do you hope people take away from the exhibition?

SATTERWHITE: It’s the most clear, succinct, and comprehensive summary of my vision that I’ve been trying to generate and develop for more than a decade, so I can build it in other mediums—as many mediums as possible. I hope that I’m more understood after this exhibition and the blueprint of my vision truly comes through. I hope that the complexities and nuances of my visual language registers with the public in a way where I can have a better conversation next time.