- Source: VOGUE

- Author: Dodie Kazanjian

- Date: February 2010

- Format: PRINT

The Body Eccentric

In an exciting range of current work, artists are finding inventive new ways to depict the figure in the contemporary world

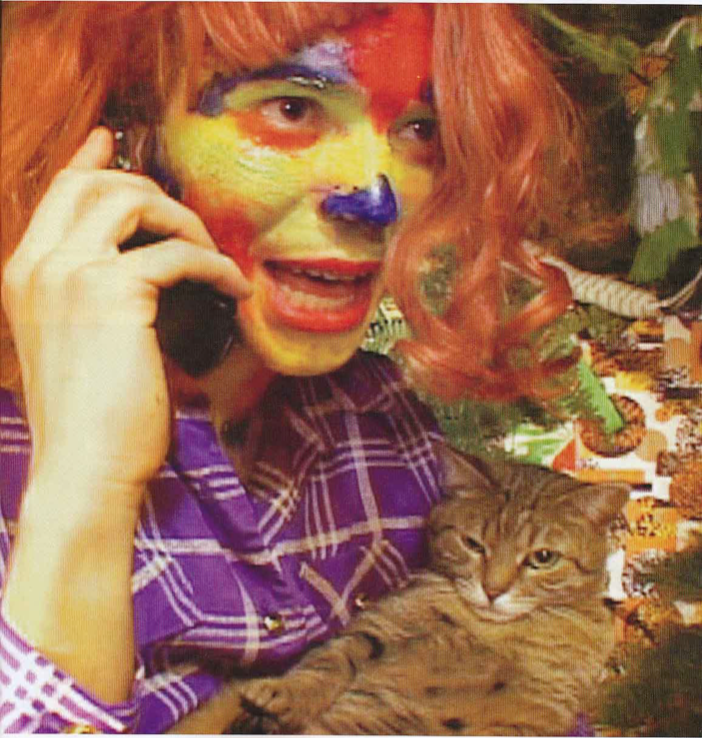

A still from A Family Finds Entertainment, 2004, an "anarchic, extreme, disjointed" work by Philadelphia-based video artist Ryan Trecartin.

The human figure is still art’s indispensable subject. A century after Kandinsky made his historic leap into pure abstraction, artists young and old keep finding new ways to make figurative art – often with abstract elements as part of the package. In the last few years, the figurative impulse has been taking a very weird turn. Grotesque, disturbing, and highly eccentric in form and conception, the work of many artists in many different places shows a pre-rational intensity that leaves the real world far behind. These artists don’t necessarily know one another or represent a movement yet, but they appear to share similar attitudes and influences. What you see her is a mini-exhibition of a trend that could be described as “eccentric figuration.”

Massimiliano Gioni, director of special exhibitions at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, tells me he’s been seeing the same tendency. (He had used the expression “hysterical realism.”) “These artists are showing characters of a personal theatre,” says Gioni. “You could say it’s the bastard child of Cindy Sherman and John Currin, a theatre where the self doesn’t matter anymore. You see not one but many selves.”

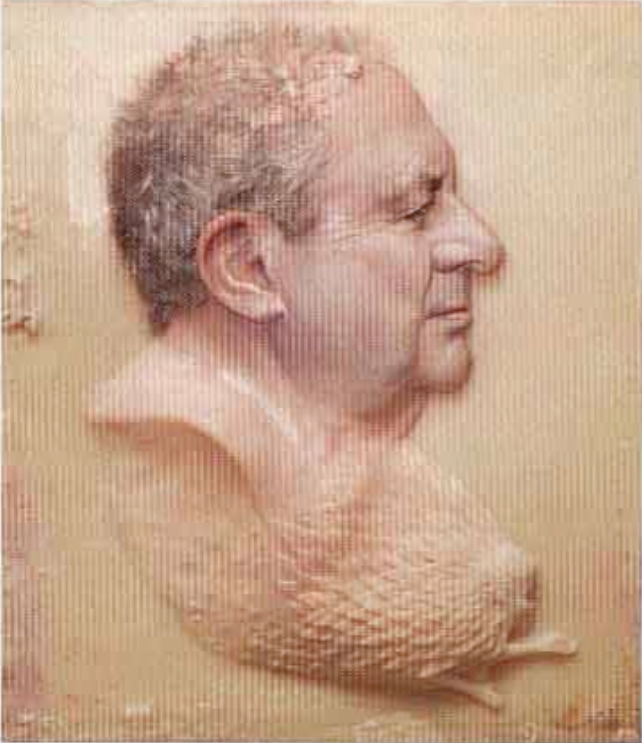

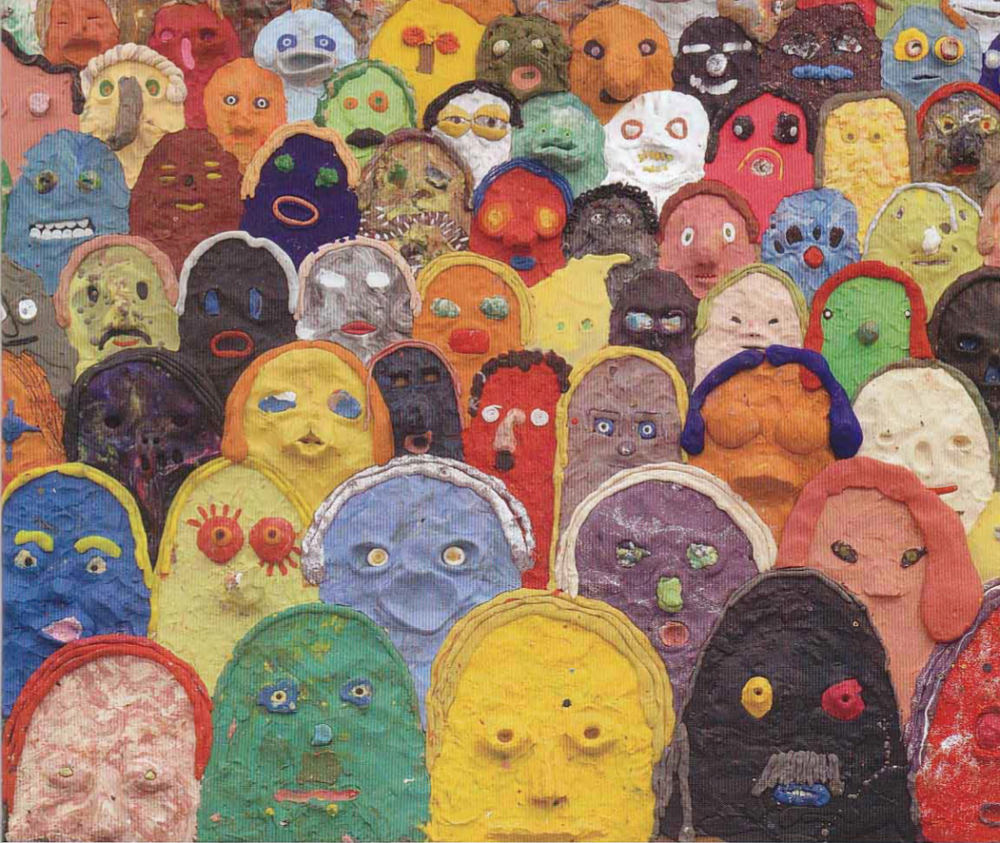

As you might expect, the artists on these pages work in every conceivable medium. Gelitin, a four-man team of artist-provocateurs based in Vienna, has created a series of imaginary portraits in modeling clay. The Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi, who made a deceptively realistic portrait in wax of the megacollector Dakis Joannou, keeps turning his own life into an eccentric artwork: He spent several years “becoming” his father – he gained weight, wore his father’s clothes, grew a beard, dyed his hair grey, and lived the same life his father was living. Cuoghi and his girlfriend now avoid quotidian distractions by living, in Milan, or Micronesian time, staying up all night and sleeping during the day. Nathalie Djurberg, originally from Sweden, tells darkly enchanted stories in stop-motion animation; her distorted clay figures are like characters in a macabre, absurdist fairy tale. Dana Shutz, bless her American heart, actually uses paint on canvas, but her characters tend to be fractured, self-devouring mutants, gorgeously painted monsters.

Mary Reid Kelley, performing in clownlike makeup in her video Sadie, the Saddest Sadist, 2009.

A detail shot of the sculpture Sneakers 1, 2008, by Zurich-based Georgian artist Andro Wekula

The sources of eccentric figuration range from Goya’s Caprichos to tomorrow’s scary headlines, from conceptual performance art to reality TV and cyberspace, from the late paintings of Philip Guston to Darth Vader to George Condo. “Figuration came to me primarily through comic books, cartoons, and movies,” Thomas Houseago, a British sculptor of hulking, Neo-primitive forms, tells me. “Those Beatles albums, like Magical Mystery Tour, created another space in my head.” So did the late-Picasso show at the Tate in 1988, tribal African sculpture, Jacob Epstein, and prehistoric art. “I felt like I had all these friends, this lineage,” he says, “this weird mix of high-low, low-high.”

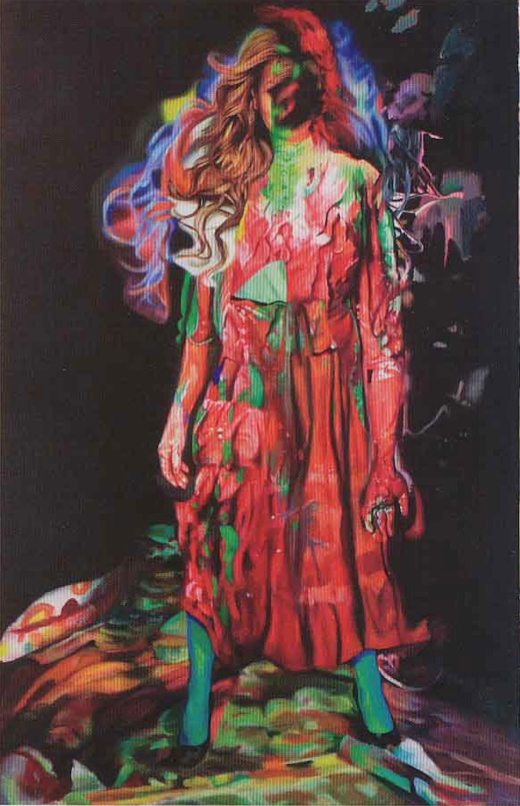

There’s no doubt about it-high art and popular culture have merged. Jeffrey Deitch, the dealer and art impresario who has done as much as anyone to erase these boundaries, says the crossover “reflects the way the culture really is right now.” Deitch’s influential “Post Human” show in 1992 explored the cultural implications of plastic surgery, genetic engineering, and other modes of self transformation. He’s now at work on a show called “Carnival,” which will deal with some of the same eccentric figurations that we see on these pages. “It’s not expressionistic or psychological,” he says. “And it’s certainly not figuration that comes from observation of the model.” The new work is straight from the artist’s imagination, or what Kandinsky called “inner necessity.” The stories it tells- and narrative is a central component here- are pure fiction, more disturbing than funny, highly theatrical, and sometimes even entertaining.

“It’s about going into another reality,” says Francesco Bonami, who is curating this year’s Whitney Biennial and who’s also been struck by the new figurative weirdness. “It’s a reality that doesn’t necessarily belong to reality, a kind of anti-digitization. Our lives are shaped by the new digital technologies. The computer can generate so many forms that it’s almost impossible to create your own style. These artists are going back to a more intimate dimension where they can find or rediscover boundaries and limits and create their own imaginary set of characters.” Thomas Houseago will be in Bonami’s Whitney Biennial, and so will George Condo, whose outrageously eccentric paintings have become newly relevant for this younger generation.

Westworld, 2009, by Francine Spiegel, who uses acrylic and airbrush on canvas

Megan Dakis, 2007, portraying collector Dakis Joannou, by Milan-based artist Roberto Cuoghi

Felt-S, 2009, by Thomas Houseago, whose sculptures reference neo-primitive forms

“People can’t get away from people,” as Condo puts it. “Guston broke the barrier of abstraction in our time and brought in this comedic, dark, ironic, idiotic, and heroic side of humanity. The thing that I look for in figurative painting is a feeling that the person walked onto the canvas, stood there for a moment, and will eventually walk off it. You’re just catching them alive at that second.”

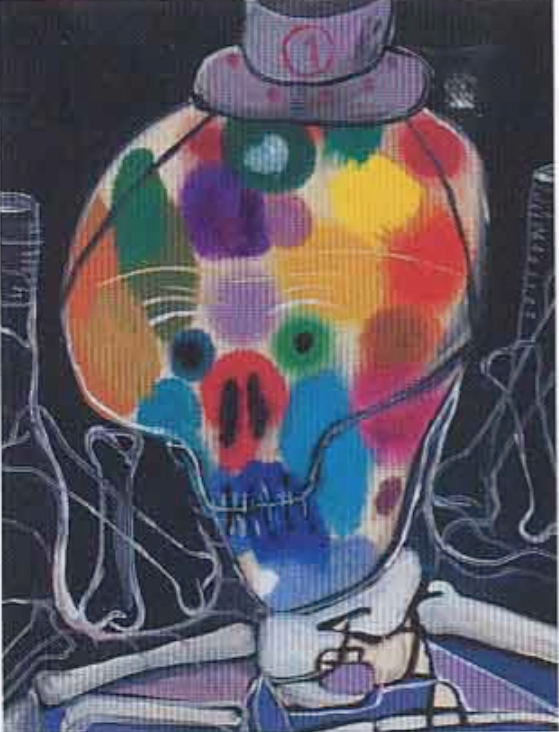

Untitled, 2008, by Polish Painter Jakub Julian Ziolkowski

The anthropomorphic cakeroast, 2008, by Cassandra MacLeod

Shaking, Cooking, Peeing, 2009, by Dana Schutz

Asked to name a young artist who’s doing something on that order today, he says, “Ryan Trecartin’s concept of figuration excites me. I like the insanity and the hysteria he puts into extremely commonplace situations. I think it mirrors the fear factor that runs rampant through the media and through people’s lives, and keeps us on edge.” Donna De Salvo, the Whitney’s chief curator, is also high on Trecartin, whose work is already in the museum. “He has an understanding of narrative that is very much now,” she says. “It’s anarchic, extreme, disjointed- things don’t really add up.”

Trecartin, 28, is an American video artist whose characters, with gaudily painted faces, often argue and bicker in fragmented conversations- in cars, in kitchens, on the telephone. His work channels transgressive downtown performance art and reality TV. “I feel part of something that is larger than the art world,” he tells me, “something that includes advertising and TV shows and journalism. A lot of people think that the new technologies are dehumanizing, but I feel like we’re becoming more human and more connected. Everyone can participate in culture and change it. This eccentric work we’re seeing right now might seem creepy, but the world is full of creep, and it’s good to show the creep and embrace it and see what productive, creative things can happen.”

Jakub Julian Ziolkowski, from Poland, moves in the opposite direction from Trecartin. Instead of engaging with the technological present, his paintings well up from deep recesses of fantasy and folklore. Like most of this new crop of figurative artists, Ziolkowski devotes obsessive attention to craft and technique. By and large, these are not conceptual, post-studio artists acting as creative directors of a fabrication team. They do it themselves, in the studio.

As Massimiliano Gioni points out, we live in a figurative culture. “You look at magazines, you look at TV, and you’re surrounded by faces. So much of what we see are faces that are Photoshopped or transformed in some way, and I think these artists are reacting to that.” Mary Reid Kelley, fresh out of Yale’s graduate school of art, writes and plays all the roles in her hypnotic black-and-white videos, which evoke past lives. In Sadie, the Saddest Sadist, wearing black, clownlike patches on her eyes and black lipstick and speaking in rhymed couplets, she portrays a munitions worker in World War I Britain, and also the sailor who give her “the clap.” I think you could say,” she tells me, “that, bad as things are today, we still have this basic human element of telling stories. Trying to imagine ourselves into other people’s lives is evidence that all is not lost.”

“The figure never goes away,” Donna DeSalvo says, “It’s a fundamental vehicle. Human identity is the one thing you can hold on to in a world that’s spinning out of control.”

Nontraditional approaches to figuration by the Viennese collective Gelitin in a 2008 untitled work made from modeling clay.

Untitled, 2008: plastiline, wood, 41 x 49 1/2 x 4 inches/Courtesy of Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Paris & Miami.

A still from the stop motion series Once removed on my mother's side, 2008, by Berlin based Nathalie Djurberg.

One removed on my mother's side, 2008: clay animation, video, duration 5:20, edition of four/Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, NYC, and Bio Marconi, Milan.