- Source: The New York Times

- Author: CHARLIE FOX

- Date: September 04, 2017

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

The Beauty of Ugly Painting

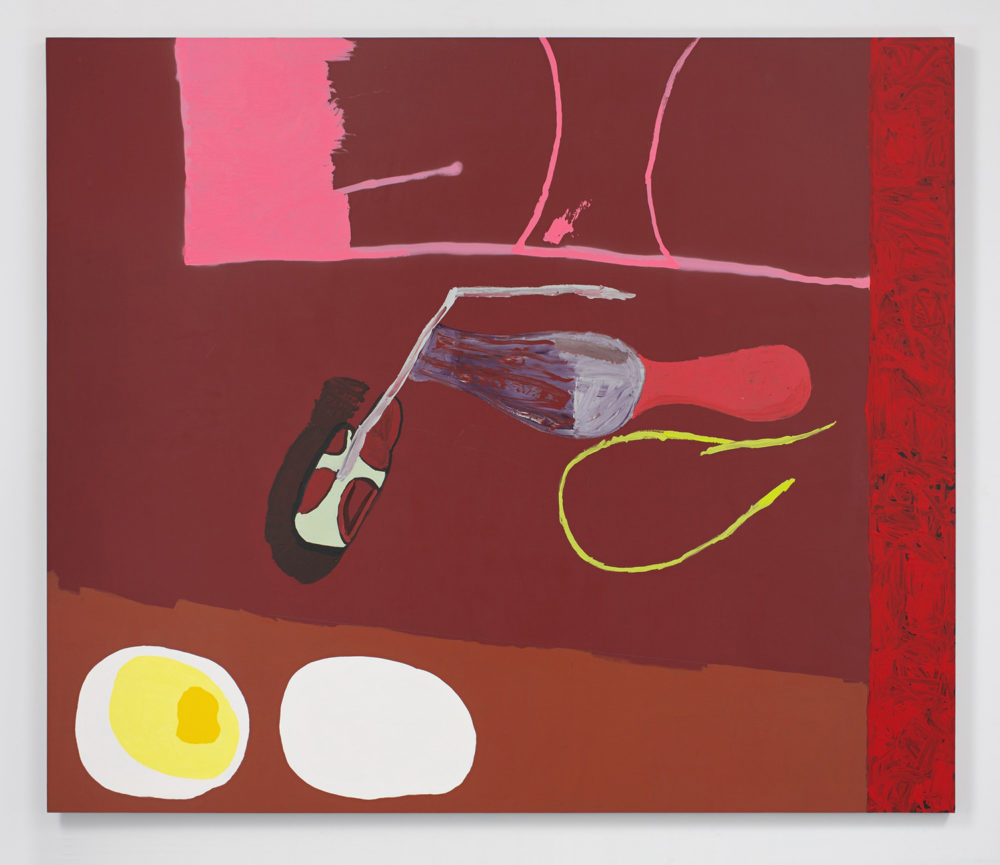

Dear Clifford Rocket, Don’t You Want a Home, 2016, by Torey Thornton, whose style combines otherworldly abstraction, collage and found materials. Acrylic paint and spray paint on wood panel, courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

Lost in the fun house of Laura Owens’s unstoppably inventive show at the gallery Sadie Coles HQ in London last year, I spent a whole afternoon eyeballing a painting of Garfield. The L.A.-based Owens transforms elements that could be too swiftly called ‘‘zany’’ or ‘‘lurid’’ — rainbow sprinkles as a psychedelic garland on wallpaper; stoned, Crayola-like squiggles; swirls of oil paint thick as cake frosting — into something ravishing. In a 2013 interview, the artist said she had no intention of making ‘‘good’’ art, art that fulfills some fussy criteria of taste or beauty; the opposite impulse, she suggested, is always more fruitful.

Owens, who will be the subject of a midcareer retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art this fall, is a master of what might be called ‘‘ugly painting.’’ As paradoxical as this sounds, the term is in fact ferocious praise. Ugly art is sloppy, wild and, yes, transgressive, exciting confusion and joy because it abandons commonplace ideas of what is — and looks — pretty. This is not a question of being merely grotesque, but daring. It’s a philosophy that harks back to Tristan Tzara, Dada’s chief theorist, who in 1918 trashed beauty as ‘‘a boring sort of perfection, a stagnant idea of a golden swamp.’’ The Dadaists were advocates for ugliness as not just a valid artistic condition, but as a way of shocking a public reeling in the midst of a hideous war.

Indeed, ugly art often reflects an ugly time. In the 1930s, the Third Reich labeled Otto Dix’s ghostlike figures with mutilated bodies ‘‘degenerate art.’’ In the late ’60s, Philip Guston abandoned Abstract Expressionism for creepy cartoons dealing with race riots and inner-city horrors. (The critic Robert Hughes scorned this work, with its depictions of panic-stricken eyes and Klansmen run amok, as ‘‘Ku Klux Komix.’’) Working against the backdrop of the Cold War in West Germany in the 1980s, Albert Oehlen conjured beasts with the most noxious colors imaginable — as in a portrait of Adolf Hitler rendered in sickly blue, pink and yellow. What exactly is deemed ugly, of course, remains in the eye of the beholder; mimicking infantile derangement is outrageous to some, a snooze to others. But what unifies ugly painting is its defiance of the obviously attractive, familiar or ‘‘lifelike.’’ It serves as a reminder that art isn’t a branch of mortuary science, providing faithful replication of lost beauties. It’s a mind-altering drug: It exists to cause trouble, knock things head over heels and show that there are other ways to see.

Our present moment bristles with an extra-special awfulness, which may explain not only the existence of this new generation of ugly painters, but the particularly freaky flavor of their work. They’ve emerged out of an especially dull couple of years in painting, during which a flood of derivative abstraction threatened to devolve the form into the kind of swank kitsch found in hotel lobbies. Ugly painting — even expensive ugly painting — defies a bloated art market, in which inoffensive works all too often become trophies. Ugliness is also a way of responding to the difficulty of being a painter now — self-conscious to the point of catatonia, asked to practice a medium that has routinely and falsely been declared dead since its inception. The route into that disorientating wilderness known as the future lies in figuring out, as the writer Donald Barthelme once wrote, ‘‘how to be bad.’’ To be willfully ugly is to be aggressively new, to trash convention and risk making work that isn’t easily categorized or understood.

And so many painters right now have become good at being ugly. The heartbreaking works of Karen Kilimnik recast the icons of consumerism and popular culture — from Kate Moss to drowsy dogs — as strangely deformed things: For a show last year at New York’s 303 Gallery, she stuck cat stickers onto reproductions of baroque tapestries. Torey Thornton’s paintings turn contextless objects — a roll of toilet paper, a lopsided pineapple, an egg — into disembodied abstractions, placing each in a scene that suggests a computer simulation of surrealism. Then, of course, there’s Owens, who performs daredevil raids on art history, borrowing from ‘‘Peanuts’’ cartoons and El Greco and seemingly every other artistic movement imaginable, chewing her plunder up into a hallucinogenic mess. Taking a cue from the ugly painters of the past, the best painters working now have soaked up styles, influences and history itself, only to unleash it all as a beautiful, unholy wreck.

Much like the ebb and flow of ugly art’s popularity, the reconsideration of ugly works — and their subsequent transformation from ugly to not-ugly thanks to the redemptive gallantry of critics, curators and collective hindsight — follows its own predictable cycle. ‘‘Woman, I’’ by Willem de Kooning, who once described himself as ‘‘wrapped in the melodrama of vulgarity,’’ is now the artist’s most celebrated work, and yet viewers were initially perplexed. Writing in The New York Times in 1974, the critic Anatole Broyard recalled being ‘‘startled’’ by the subject’s ‘‘ferociously bared teeth and menacing hyperthyroid eyes,’’ finally declaring, that ‘‘like all acts of drastic originality,’’ de Kooning’s paintings ‘‘take some getting used to.’’

The most unmistakable symptom of the art world’s present embrace of the age of ugliness is that artists who have skulked the margins of art history for years by ignoring any sort of accepted notions of aesthetic beauty are increasingly receiving institutional recognition, such as Llyn Foulkes, who once produced a self-portrait in which Mickey Mouse burrows through his skull. Then there’s Francis Picabia and Sigmar Polke, who have both received retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art in the last few years. Two outrageous polymaths who left their kinky imprint on whatever they touched, Picabia and Polke acted as if painting were a prankster’s task, cracking jokes and enacting wicked provocations through the medium. A self-proclaimed ‘‘beautiful monster’’ and thoroughly a Surrealist’s Surrealist, Picabia painted arch rip-offs of Impressionism in which lovers resemble smooching gargoyles. His assault on good taste was so grotesque that by 1921 he had renounced even Dada, albeit with the ultra-Dadaist proclamation that ‘‘I believe in happiness and I loathe vomiting.’’

Polke dealt with the patricidal energies stoked by World War II by mixing together the traits the Third Reich imputed to so-called degenerate art — Modernist, Surrealist, Impressionistic — a Dr. Jekyll playing with chemicals in the lab, making art that was perverse, anarchic and acid in its critique of German capitalism. Polke’s enormous ‘‘Paganini,’’ 1981-83, looks like the work of multiple deviant hands, incorporating an etching of the devil mid-fiddle solo, fogbound expanses spiked with graffiti swirls and a stencil of a jester turning a skull into a radiation symbol. It’s a panorama of a diseased environment — or, given the artist’s mystical slant, a record of some sinister alchemical process.

But it was Martin Kippenberger, another German, who found new turf throughout his career simply by being crude, and whose influence might have most infected our current ugly era. Living up to the degenerate tag in his own crazed way (see the self-portraits in which he reminds one of a drunk troll in his underwear), Kippenberger was equal parts Picabia and Andy Kaufman. He bought a gas station in Brazil, dedicated sculptures of lampposts to Santa Claus and, even as he worked like a demon, pretended painting was just a distraction from his relentless carousing. His 1982-83 portrait of Lemmy, leader of the English rock band Motörhead, shirtless and posed before a Confederate flag, is fuzzy, as if he was too soused to keep the scene in focus.

Kippenberger died in 1997 at the age of 43, and like his predecessors in bad taste, his reception during his lifetime was mixed. But in the years since his first major American museum retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 2008, Kippenberger’s legacy has become so huge and mutant it could be split among six radically different artists. Some of its most unusual aftershocks appear in the art of Sam McKinniss, who is based in Brooklyn. As with the fun-loving ogre, McKinniss has a penchant for sweet but sickly textures and assumes the role of painter with irreverence, attending to supposedly kitsch subjects: Winona Ryder in ‘‘Beetlejuice,’’ Michael Jackson, the rapper Cam’ron in a pink fur hoodie. He makes everyone lush and eerie, the paintings hailing from the fancier suburbs of ugliness: homages to Fragonard, but painted by some kind of undead dandy. You can O.D. on the tongue-in-cheek prettiness of his painting’s soft-focus glow or marvel at the discreetly dysmorphic bodies of his subjects. This year, McKinniss provided the cover portrait for goth pop chanteuse Lorde’s album ‘‘Melodrama,’’ in which the singer lies in bed like an insomniac princess. It’s sexy and odd; the oozy play of color across her face (pink, winter blue, peach) suggests Christmas lights on a Disney snow. Sly details disconcert: The photographic verisimilitude slips away when the covers’ outline gets fudged, and the paint sometimes runs — a weeping heroine’s makeup. With these bewitching pictures, McKinniss provides a millennial illustration of the wise words haunting the best ugly art — was it Jean Genet or John Waters who said, ‘‘to achieve harmony in bad taste is the height of elegance’’?