- Source: Art Basel Magazine

- Author: Brian Keith Jackson

- Date: December 1, 2021

- Format: Print

THE ART OF, AND FROM, HEALING

For British Nigerian painter Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, the restorative power of art is viscerally realized through his latest work.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones in the studio.

When I reach British Nigerian painter Tunji Adeniyi-Jones at his studio, he’s just returning from physical therapy to address lower back issues. “My lower half isn’t as strong as it should be, so I do all the lifting with my top half,” says the 28-year-old New York City-based artist. He’s trying to strengthen his glutes. “I’ve aged during the pandemic, in myriad ways. Time is just, like, it’s been five years’ worth of emotional aging and weight.”

That transitional pull of time is evident in his latest dreamlike paintings for his first UK solo exhibition, ‘That Which Binds Us’ at White Cube last November, as well as new work that will be on display with Morán Morán gallery at Art Basel Miami. The impetus of this body of work stemmed during fall 2020, while Adeniyi-Jones was at Black Rock Senegal, the artist residency started by artist Kehinde Wiley.

“I was ultimately in this place that was still so foreign,” says Adeniyi-Jones, who was born and raised in London, of his time in Dakar. “I had no connections or ties but felt so connected. I felt the ability to be a Black body in a space and learn and experience without having to be a minority. There were moments I was like, ‘Damn, I haven’t seen a white person in weeks.’ It was a compounded experience, which I think some people can’t understand, which is valuable too.”

Dakar, the space and lack of pressure, as it pertained to time and just being, allowed Adeniyi-Jones to broaden his visual vocabulary. The concept of fluidity, migration and immigration have always been a cultural foraging field for Black and brown existence. He has used his work to explore the navigation of space, allowing his vibrantly colored characters, figures, to become less specific to his prior oft-referenced Nigerian Yoruba characterized imaginings, and more about the ambiguous body and form, reflecting a transcultural experience, within Blackness.

Having trained at two long-noted bastions of white privilege (Oxford for his BA and Yale School of Art for his MFA), Adeniyi-Jones was continuously revisualizing how to navigate space, exploring his own voice and history, rather than being beholden to what he felt was expected of him as a young Black painter within the consideration of the white Western gaze. “Inevitably, I do think I’ve fallen victim to that [what they want from me] for a large period of my life, in terms of the work I was making right after undergrad. It’s a thought process that I’ve been gradually undoing and unmaking within myself,” he says. “I became more reflective when I moved to America. I was able to analyze my Britishness from a distance, and that distance is important when looking at the versions of myself”

“The characters in my work are about movement, the conditions by which a different kind of cultural context, of country and environment. History. In that process, I’ve added so many layers, just to myself, outside of the work.”

In light of a global pandemic, the discourse, like his work, has broadened when, perhaps, for the first time the movement of whiteness is also impacted, forcing the dominant culture to reevaluate their navigation of space, here on Earth.

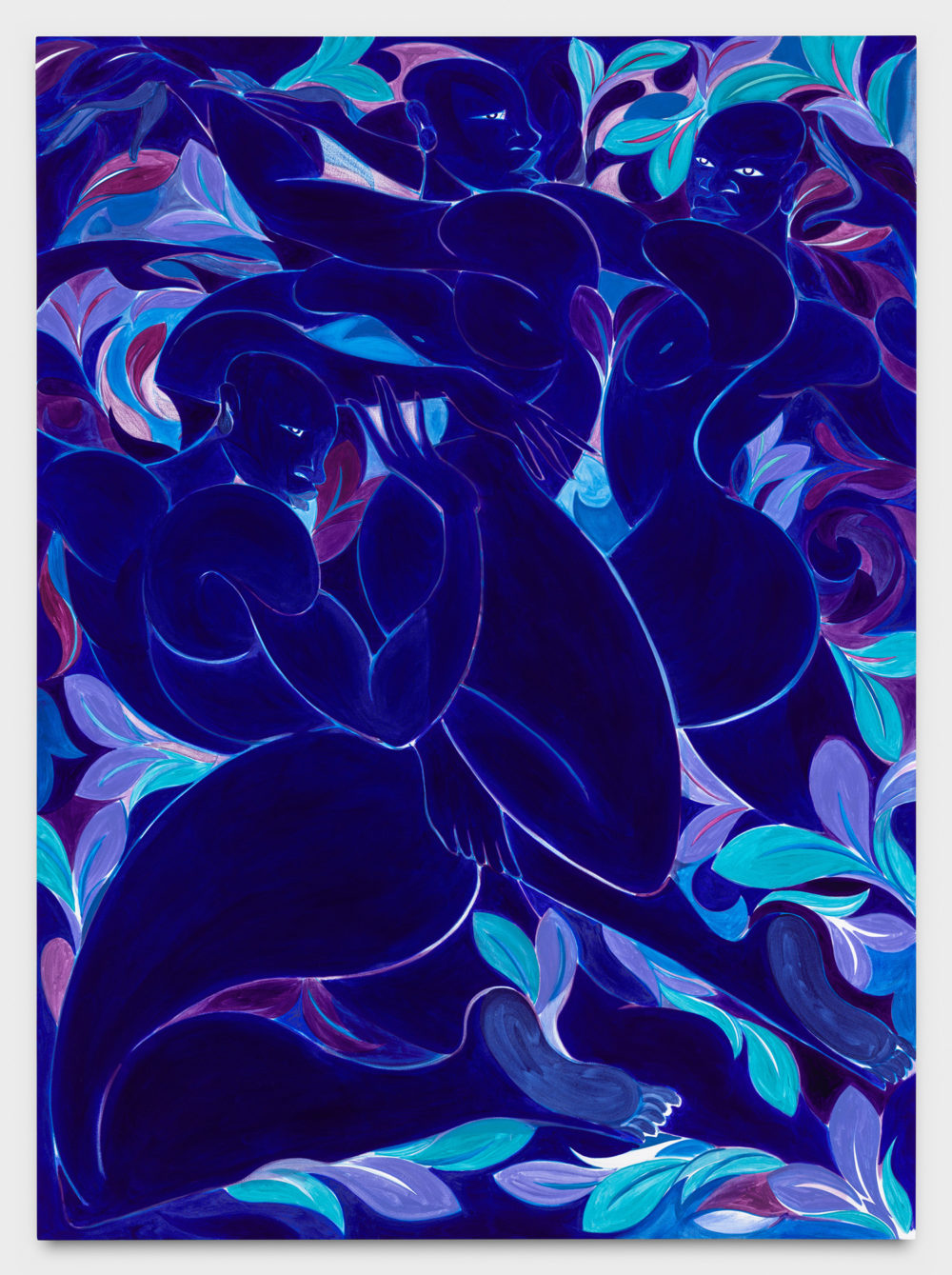

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

Verdant Youth, 2021

Oil on canvas

82 x 60 inches

(208.3 x 152.4 cm)

Photograph by Stan Narten

“There will continually be a push back between any sort of mandated, restrictive ‘you can’t go here or there,”‘ he says. “It’s a completely foreign phenomenon, specifically for white people in America, but also Europe. They aren’t used to it.”

With his new sense of exploration, and the vastness therein, he’s pushing those boundaries in his work. The figures are no longer just the focus. Adeniyi-Jones is highlighting the ornamental and patterned aspects, amplifying the surroundings that are environmentally present, placing his figures in a active existence. Through his spiritlike characters, he’s going within himself, searching for an organic manifestation, the process and translation of grief.

There are gestures where you can see his initial touch of the canvas, the under drawings of the painting peeking through these pockets of imperfection, the unfinished edges, and the tension that comes when something is clearly made by hand, the quiet moments in things, otherwise large at first sight.

But while playing with various layers, through the difficulties of the pandemic, he was also in the process of purging. In November 2020, shortly after his stay at Black Rock, his father passed. It was that which propelled him not only to physical, but mental health therapy as well.

“There was a flipping of my headspace into the moment of, obviously, survival mode. Trying to take care of everything, but also eliminating empty calories’ worth of emotion and time for certain people.”

It brought to the fore the pressures and demands of young artists trying to make their way, living up to promised expectations, even during a pandemic, a time of loss, of constant reflection, that the viewer rarely knows or cares about. “[My father’s death] is the most real thing in my life, but people aren’t trying to hear about that or address it,” he says. “It’s not the reality wanted from a young painter who is doing all these great things. It’s not their romantic notion.”

“All this work I’ve made in the last year are grief paintings. I’m making these to make myself feel better, at the core of absolutely everything. That’s a conversation I’m not having as much as I’d like to. I’m not the only person who lost someone over the past year, far from it, but it’s weird how no one is talking about that shit or the effect that can have.”

His new works and the growth they expose speak to the power of art, not just as a practice, rather the release that comes with its creation. A lifeline to pull away from the barreling siren sounds, often associate with life, and market. “For six months, I was like, Am I ever going to be able to paint again?’ I’m happy I can. I’m being more productive than I’ve ever been. I’m driven. But the full picture is important,” he says. “This work is making me feel better, which is a blessing. The healing happening in real time, through the work, is a real thing.”

Losing a parent, for anyone, is a difficult process, but as an only child of immigrants, which Adeniyi-Jones is, it contains a different physical, visceral and mental grasp. “I’ve always thought about why I paint bodies, or people will ask that question, maybe looking for something more specific,” he says, aware that his answer is not complicated. “I do it because I like their presence and the support that offers in other ways. Me bringing all these bodies out here and presenting them, then kind of crowding myself in the studio with them, is like they’re a force field, protective bodies. This is how they function for me.”