- Source: Ocula Magazine

- Author: Vivian Chui

- Date: April 27, 2022

- Format: Online

The 2022 Whitney Biennial Expands the Scope of ‘American’ Art

Ellen Gallagher, Ecstatic Draught of Fishes (2022). Oil, pigment, palladium leaf, and paper on canvas. 248 × 300 cm. Exhibition view: Whitney Biennial 2022, Quiet as It's Kept, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (6 April–5 September 2022). Photo: Ron Amstutz.

The eightieth edition of the Whitney Biennial in New York (6 April–5 September 2022) takes the pulse of contemporary art in America as the storied museum has done since 1932, and in contrast to the pronounced political undercurrents of the past two biennials, Quiet as It’s Kept feels distinctly lacking in thematic structure.

As explained in the exhibition statement, co-curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards intentionally eschewed specific conceptual umbrellas for a full panoply of ideas, with 63 participating artists showing works borne out of diverse intentions and processes, forging an intersection of discourses that have emerged in the wake of a global pandemic, violent insurrection, and renewed calls for racial justice.

Alfredo Jaar, 06.01.2020 18.39 (2022) (still). Video projection, sound, and fans. 5:20 min. Collection of the artist. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York/Paris.

Works by established heavyweights such as Harold Ancart, Alfredo Jaar, and Adam Pendleton, as well as a selection of videos, photographs, and mixed-media works by the late artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, whose practice has witnessed resurgent interest in recent years; collide with a generation on the precipice of new heights, among them, Aria Dean and Cy Gavin.

A handful of deceased as well as international artists joined their ranks, paying tribute to those who continue to influence contemporary practices today, while expanding the parameters of what is traditionally thought to be ‘American’ art.

Occupying two upper floors of the museum, with a handful of works scattered elsewhere, the exhibition is made of two opposing halves: the sixth floor—a complex of dark, tightly configured rooms containing largely isolated works, and the fifth floor, a light-filled atrium where paintings, sculptures, videos, and installations interacted.

Overall, the Biennial—as with most presentations of its kind—teeters on the edge of being overwhelming, while exerting commendable efforts to pose challenging questions and display impressive technical skills.

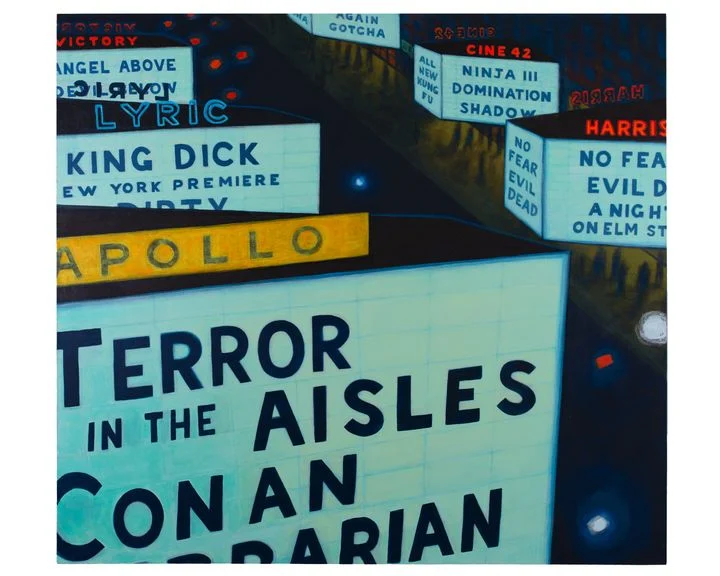

Jane Dickson, Big Terror (2020). Acrylic on linen. 165.1 x 185.4 cm. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Whitney Biennial 2022.

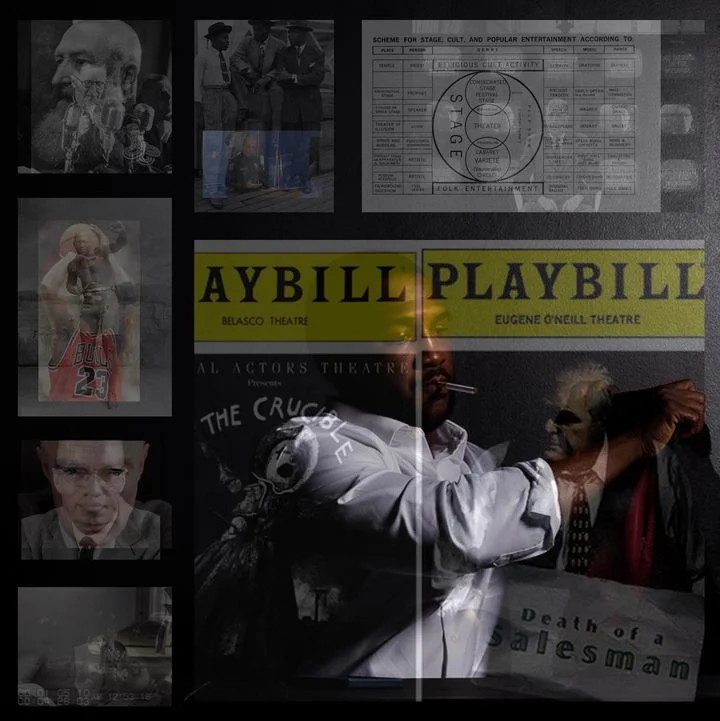

Video works dominated the sixth floor, with many standouts. Kandis Williams’ striking four-channel installation Death of A (2022) is a powerful reinvention of Arthur Miller’s 1949 play Death of a Salesman, which famously critiqued the ideological pitfalls of the so-called American Dream.

In this new take, a single actor recites, acts out, and dances through a script, blending lines from the original play with texts by figures such as Albert Einstein and Yvonne Rainer, in a poignant performance that conveys the maddening pressures capitalism places not only on individuals, but particularly Black men.

Kandis Williams, Death of A (2021) (still). Installation, four-channel videos, colour, sound. 26:51 min. Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán.

Williams—whose 2021 exhibition inaugurated David Zwirner‘s venture 52 Walker, conceived as a direct response to the lack of diversity within the commercial art industry—juxtaposes the script with a kaleidoscopic montage that splices together scenes of basketball superstars, nuclear mushroom clouds, African artefacts displayed in museum vitrines, and Hollywood portrayals of Black lives in America.

These disparate images flicker across an adjacent projection screen as the video work’s protagonist struggles with inner turmoil, mounting a scathing exposition of the psychological anxieties that mass media, culture, and politics impose on consumers.

Nearby, Albuquerque-based composer and performance artist Raven Chacon highlights the work of First Nations women musicians, with printed notations from his ‘For Zitkála-Šá’ composition series (2017–2020), and a more recent video installation Three Songs (2021).

The latter casts an intergenerational trio who sing with poignant clarity in their native tongues, about the past violence, present conditions, and future hopes of Indigenous communities. The women, each beating a single snare drum, embody an impactful means of harnessing sound for remembrance and resistance.

Trinh T. Minh-ha, What about China? (2021) (still). HD video, colour, sound. 135 min. © Moongift Films. Courtesy the artist and Moongift Films.

Extending forms of resistance on the sixth floor is What about China? (2021) by Trinh T. Minh-ha, a film that displaces the notion of harmony often touted within Chinese culture. Made of up grainy footage shot during the early 1990s, the film hones in on the unique architecture and atmospheric surroundings of villages and settings dating back to ancient times.

The artist, as the video’s narrator, ruminates on traditional values and the ideological divisions between rural and urban individuals in modern China, while casting a deeply intimate view of the people who inhabit these settings. The only criticism to be found here is that its two-hour duration felt ill-fitted for a biennial setting, especially one in which multiple lengthy video works stretch viewers’ attention spans to its limits. Hopefully, a dedicated screening will be presented at some point during the exhibition’s run.

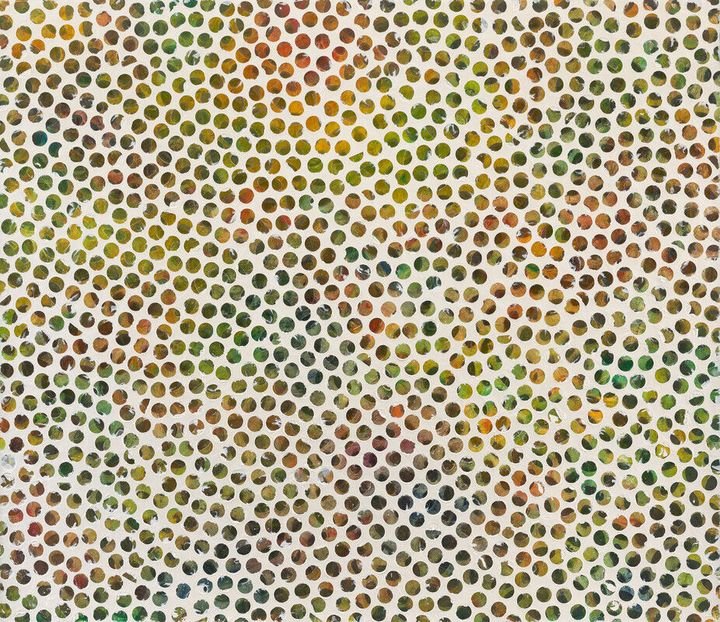

Downstairs, abstraction emerges as a dominant sub-theme. A suite of recent paintings and works on paper by Matt Connors taps into the legacies of Minimalism and Abstract Expressionism, in vibrant compositions that are fluid and ambiguous in meaning, whose visuals made up for a room broken up by wall-partition displays that functioned as lacklustre vessels for otherwise outstanding works.

The Chicago-born painter taps into the legacies of past art movements in paintings like I / Fell / Off (after M.S.) (2021), whose vertical red and pink stripes are demarcated by black striations reminiscent of a Rorschach test, transforming graphic lines and shapes into vehicles for chance and introspection.

Woody De Othello, study for The will to make things happen (2021). Courtesy the artist; Jessica Silverman, San Francisco; and Karma, New York.

James Little and Duane Linklater also adopt abstraction as a primary tool for communication. But while Little—a contemporary of pioneering painters such as Ed Clark and Jack Whitten, with whom he abandoned the social realism dominant among Black artists during the 1960s and 70s—regards abstraction as the only visual means towards absolute freedom, Linklater uses it to convey the severe sufferings that white colonialists inflicted upon First Nations peoples, which in his view, could never be captured by figuration.

Within the Biennial, Little presents recent works wherein thick applications of white paint are masterfully stencilled atop frenetic colour fields; another suite of paintings, made up of precisely rendered geometric patterns alternating in varying shades of grey, were on view upstairs.

Linklater’s monolithic works, each cut from tipi cover patterns, command attention as they hang from the ceiling at the centre of the gallery. These linens and canvases bear markings from materials such as sumac and tea, which were left to dry outdoors as a way of registering organic records of the artist’s ancestral land.

Woody De Othello, study for The will to make things happen (2021). Courtesy the artist; Jessica Silverman, San Francisco; and Karma, New York.

Beyond abstract paintings, Woody De Othello, a rising star from California’s Bay Area, put his ceramic skills on prominent display with the installation The will to make things happen (2021). Referencing the importance of self-care during an era inundated with ‘trauma’ and ‘bad news’—in the artist’s own words—the sculptures lend a surrealist twist to vases resting above commonplace household objects rendered in larger-than-life scale.

De Othello’s sculptures embrace themselves with anthropomorphic limbs, projecting the comfort in domesticity many of us have found over the course of the pandemic. Far from simplistic, these objects emblemise current conditions with whimsy and originality.

In its entirety, Quiet as It’s Kept serves up apt metaphors for the current state of America: a tale of two diametrically opposed halves—a diverse hotbed of ideas and methodologies that defy categorisation. Revelling in difference—not just of opinion but of style, focus, and approach, it pushes for meaningful exchanges between objects and viewers alike. —[O]