- Source: HYPERALLERGIC

- Author: BRIDGET QUINN

- Date: MAY 29, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Spotlighting Lesbian Artists as Central Players in California’s Queer History

Lesbian contributions to gay life and liberation have long been overshadowed, including in the art world.

Gilbert Baker, Original hand-dyed and sewn 8-color pride flag (1978), hand dyed, screenprinted, and sewn fabric: powdered-coated (image courtesy the GLBT Historical Society)

OAKLAND — Visiting Queer California: Untold Stories at the Oakland Museum of California almost feels more like pilgrimage than casual museum-going. Here you will find touchstones of overlooked LGBTQ+ history in the Golden State. Such omissions are big themes in an exhibition packed — sometimes overwhelmingly — with objects, from fine art to private photo albums, posters, flyers, buttons, stickers, costumes, board games, newspaper clippings, zines, interviews, and films. Curator Christina Linden cautions that even so, this is no exhaustive retrospective. Of course, no one show could be. Instead, Queer California seeks to highlight too-often overlooked communities by examining, for example, transgender art and experience, or Indigenous queer culture of the past and of today. And one of the most revealing aspects of Queer California is how it repositions lesbians as central players in queer history and art.

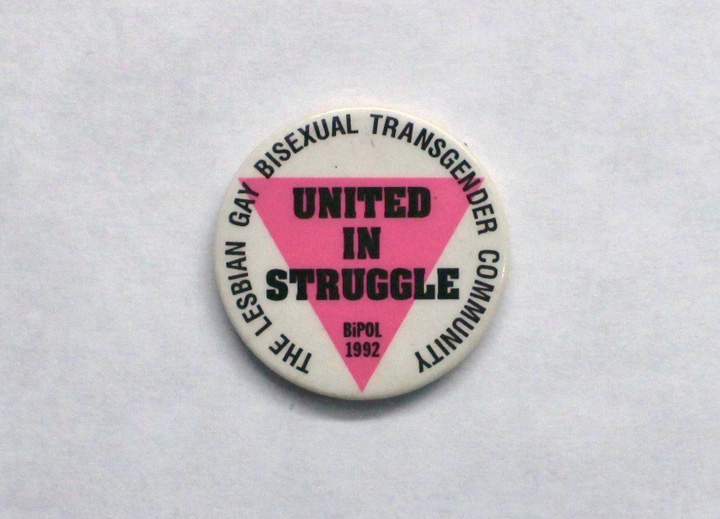

Buttons from the collection of Maggi Rubenstein: UNITED IN STRUGGLE BiPOL 1992. THE LESBIAN GAY BISEXUAL TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY (image courtesy the GLBT Historical Society Archives)

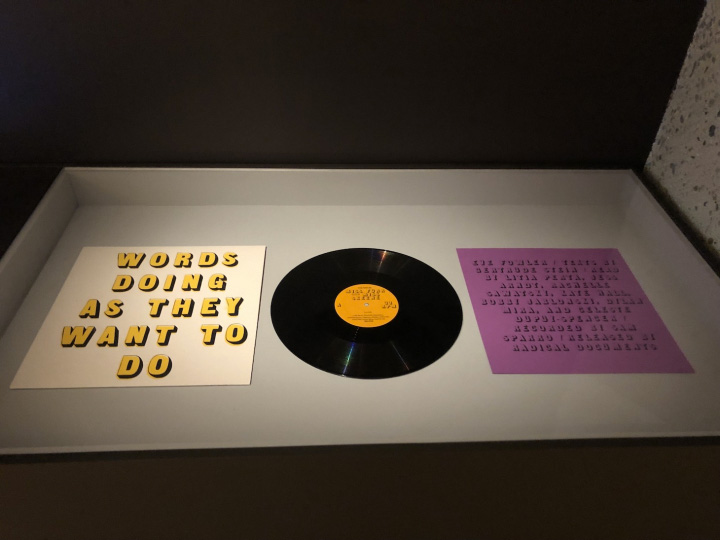

Near the entrance is a vitrine with a vinyl record beside its sleeve, with yellow lettering that shouts: WORDS DOING AS THEY WANT TO DO. It’s a 2018 work by Los Angeles artist Eve Fowler recording lesbian and trans Californians reading Gertrude Stein’s 1922 prose poem, “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene.” In Steinien “rose is a rose is a rose” fashion, words are oft repeated. In this particular poem, Stein uses “gay” 139 times in some 2,100 words (“They were very regularly gay. To be regularly gay was to do every day the gay thing that they did every day”). Via this work, the exhibition credits Stein with coining “gay” as happy shorthand for homosexual.

Fowler’s recording captures the giddy freedom of being gay and saying so (again and again). I lingered by the vitrine listening to Stein’s story from a speaker overhead. It’s hard to hear “gay” more than a hundred times and not feel cheered, and it’s a winning kick-off for queer history in an Oakland museum, as local and stage-setting as anyone could hope for.

A young person working in the gallery asked if I had questions and when I didn’t, remarked, “I was surprised to find out Gertrude Stein was from Oakland.” I did know that California’s most influential Modernist — as both author and art collector — was local, though people tend to associate Stein with Paris, so I nodded in understanding. But what came next was shocking: “Not many people realize that Gertrude Stein was a lesbian.” This is widely known, I insisted. But the gallery attendant persuaded me that the lesbianism of Gertrude Stein is now often overlooked, even sometimes forgotten.

Later, after poking around the internet and speaking with folks a lot younger than me, I discovered that Stein is remembered for a great many things — poet, collector, mentor, modernist pioneer, Parisian — before her love of women. Stein’s sexual orientation is these days mostly mentioned in passing — “her partner Alice” — rather than made central to her story. This is no doubt a kind of progress, but something of history, and of herself, is also lost.

Lenn Keller, “Black lesbian glockenspiel player w/ SF Lesbian & Gay Freedom Band, SF Pride Parade” (June, 1983) (courtesy H. Lenn Keller)

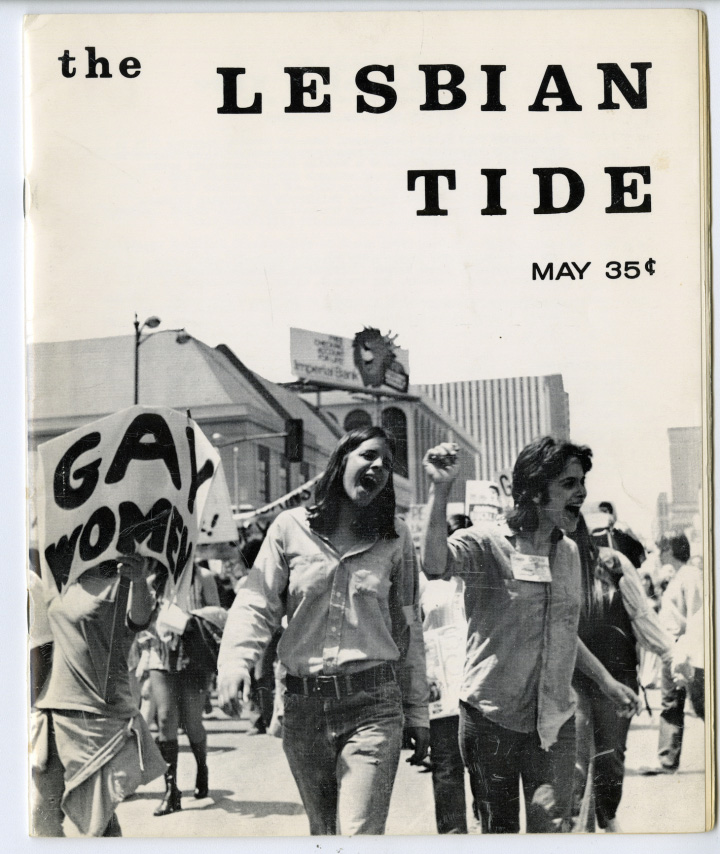

While Stein’s lesbian erasure may be surprising, it’s clear that lesbian contributions to gay life and liberation have long been overshadowed by those of gay men. The art world is one obvious example. While gay men are legion in American art — Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring, among many more — lesbian artists have been nearly invisible (even given the limited ranks of women acknowledged by mainstream art history). Such underrepresentation isn’t restricted to fine art. When Oakland Museum curators went looking for pieces for the show, they found the majority of material in archives across the state was dominated by that of cisgender gay white men. Fortunately, there’s also a lesbian archive in the museum’s backyard.

Lenn Keller’s large, black-and-white photographs documenting Black lesbian life in San Francisco in the 1980s and ’90s hang directly across from Fowler’s Stein piece, updating and expanding local lesbian art and history. Keller’s images, such as “Black lesbian glockenspiel player w/ SF Lesbian & Gay Freedom Band, SF Pride Parade, June 1983,” offer an alternative history of everyday California life. Keller saw the need for documenting and making visible her Black lesbian community at a time when “gay” had mostly come to mean white men. In addition to producing decades’ worth of photography and filmmaking, about five years ago Keller co-founded the Bay Area Lesbian Archives: a bulwark of material artifacts against a disappearing history.

Disappearance is one of the show’s major themes. Anchoring the far end of the entry space is the 1978 “Prototype for original 8-color rainbow flag” by Gilbert Baker (whose posthumous memoir, Rainbow Warrior: My Life in Color comes out June 4), done in collaboration with Lynn Segerblom and James McNamara. Rainbow flags fly by the hundreds in the Bay Area on any given day. But this one is a kind of sacred artifact, as spiritual and moving as any arm bone of a saint. Seeing the rich colors and visible stitching of the “original” rainbow flag is stirring. As are its two additional colors, not found on big flags flying over the Castro in San Francisco — or anyplace else.

Amanda Curreri, “Misfits 1979 (Sex and Art)” (2013), hand-dyed, screen-printed, sewn fabric (image courtesy the collection of Amanda Curreri)

Baker had a symbolic idea behind each color: red meant “life,” orange “healing,” yellow “sunlight,” green “nature,” indigo “serenity,” and violet was “spirit.” His original flag also included hot pink for “sex” and turquoise for “magic/art.” But hot pink and turquoise can’t easily be mass produced, so were left out of later iterations. A queer flag without sex and art? Ouch. Amanda Curreri “corrects” this sin of omission in her 2013 piece, “Misfits 1979 (Sex and Art),” a hand-dyed flag of pink and turquoise that hangs directly behind Baker’s.

Another kind of corrective appears in Laura Aguilar’s nude photographs of herself and friends in California landscapes. Aguilar, a Latina artist who passed away last year, offers the female body as Great Goddess, curvy and ample and in nature. Other images show patrons at the Plush Pony, “a working-class lesbian bar” in Los Angeles frequented by Mexican and Chicana women from the 1960s until its demise in 2008. Women in bars, as natural as any California landscape.

Kaucyila Brooke, “The Boy Mechanic” gallery view (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

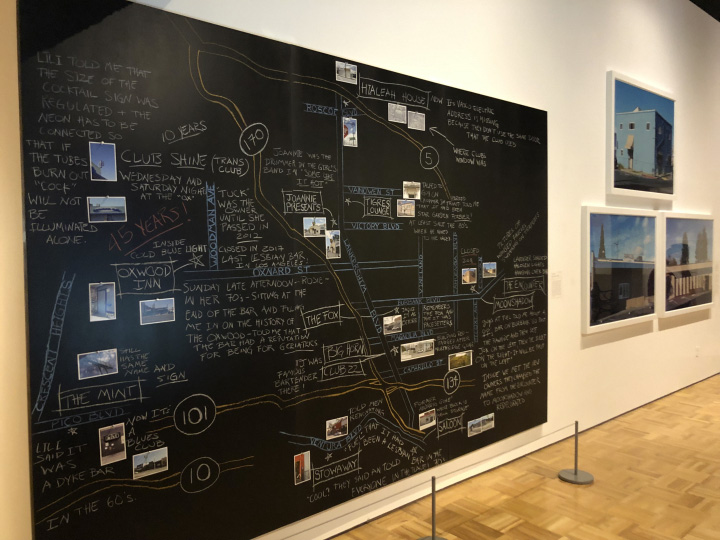

Lesbian bars are also central to one of Queer California’s most compelling works, Kaucyila Brooke’s “The Boy Mechanic,” an ongoing project begun in San Diego in 1996 that here documents lost lesbian bars of California in various ways. There’s an intricately researched and reported wall map, a framed list of bar names, divided by theme (“Girls”; “Naughty”; “Misc.”), and big-framed color photographs displaying bar exteriors, nostalgic and moving emblems of the architecture of loss.

Queer California packs a small space with more than 200 years of queer culture. It can feel hard to parse, but it’s also abundant, fecund, flourishing. Even within much oppression and loss, Queer California mostly feels celebratory and hopeful. Insistently flying the flag of art magic.

Queer California: Untold Stories continues at the Oakland Museum of California (1000 Oak St, Oakland) through August 11. The exhibition was curated by Christina Linden.