- Source: The Brooklyn Rail

- Author: Thomas Micchelli

- Date: October 1, 2006

- Format: Digital

Silence Is The Only True Friend That Shall Never Betray You

Dash Snow

Dash Snow started taking Polaroids at the age of sixteen to reclaim pockets of lost time: countless nights of hard partying that neither he nor his friends could remember the following day.

Not a promising career track to be sure, but the images that trailed in his wake—scatterings of bleached-white coke, moist tawny flesh and Formica-red blood—were evidence of a reckless but real talent, a meth-aesthetic cocktail of rank prurience, beastly humor and shimmering beauty that forged an offal-stained link with an earlier generation of participant-observers who chronicled their personal demimondes by redefining the camera shutter as the window of a confessional. But even at their most outrageous, figures like Peter Hujar, Larry Clark or Nan Goldin retained an artist’s self-consciousness that lent their shots a gloss of formal structure and high Modernist style. Snow’s photos display none of that. Instead, they smack of life on the run—unmediated, flash-lit moments without an instant of forethought. No theory, no history, no design; Snow took the pictures and the art just happened.

The relatively few photographs (mostly black-and-white, large-format C-prints, though a sampling of Polaroids linger) included in Snow’s current exhibition, Silence Is the Only True Friend That Shall Never Betray You, are unframed and pinned informally to the wall. Yet the scenes they record—a naked bather at the edge of the concrete culvert known as the Los Angeles River, a bare-chested dancer silhouetted on a rooftop, a young bicyclist racing across a wide slick of water— feel more distanced and studied than his earlier work, lacking much of its darkling menace.

But the photographs are a sidebar to an installation that marks a sharp turn from the Polaroids and builds on Snow’s recent experiments with found objects. The majority of the show, mounted in Rivington Arms’ front room, consists of sixty-odd collages, assemblages, paintings, mixed media works and one luridly colored C-print of Kenneth Anger. The gallery’s back room is dominated by a six-foot-square by ten-foot-high “book fort” composed of hundreds of decades-old books of a certain paranoiac bent , piled into four chest-high walls. A smudged white canvas tarpaulin, attached to the room’s skylight, rises from the book walls like a tepee or the woozy ghost of a rank-and-file Klansman. (An inscrutable photograph of a robed figure draped in what looks like a twisted hospital curtain looms over the book fort, reinforcing the Klan association.) On the floor, two cheap, sixties-era portable phonographs run their needles over mock LPs emblazoned with flower-power catch phrases, emitting an irritating and inescapable haze of white noise.

The book fort may embody the countercultural spirit of the show, but its bulk and gravity also seem to trap it. And most of the other three-dimensional works, bristling with drug paraphernalia and cigarette butts, feel like holdovers from the Grey Art Gallery’s Downtown Show last winter. But Snow’s collages, hung cheek-by-jowl in the front room, unframed and attached like bug specimens to the wall, prove so irresistibly seductive that it’s hard to think you’re not being snookered.

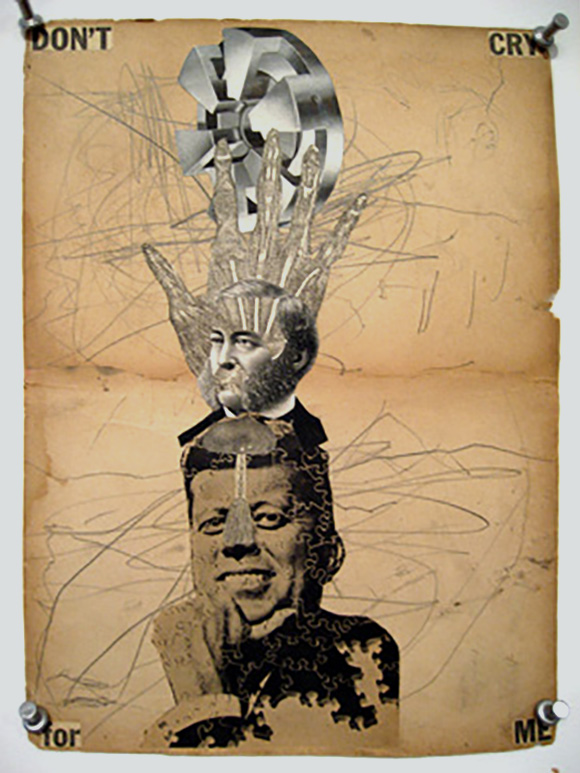

Using cheap, yellowing blank book pages, ratty cardboard backing, snippets of newsprint and moldering clippings of quaint vintage porn, Snow slices and pastes a heterodox multiplicity of images into strikingly organic icons of unadulterated automatism. The confounding historical aspect of Snow’s new pictures is that they ape, in both spirit and technique, the great Dada photomontages of Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, Raoul Hausmann and Rudolf Schlichter, to name just a few, which were so splendidly arrayed at the Museum of Modern Art this summer. But it’s not just Dada: a hundred voices echo through these works, from Fluxus and Arte Povera to Cy Twombly and Barbara Kruger, not to mention Bruce Conner and Kenneth Anger.

Dash Snow, “Don’t Cry For Me” (2006). Collage on paper. 11”× 8”. Courtesy Rivington Arms.

The same raw unselfconsciousness that made the Polaroids so indelible now seems to afford Snow a paradoxically bulletproof brand of originality. Just as it’s preposterous to posit that the artist, given his barely lucid state, could have been thinking of Larry Clark or Nan Goldin as he snapped pictures of his own orgies and drug use, the very fact that his influences here seem so overt becomes a compelling aspect of his artistic personality. It’s a rare artist who mines an art form with such abandon that anxiety over influence doesn’t come into play. To take it a step farther, it is perhaps the references we read into Snow’s imagery that tell us more about our historical moment than his own forceful but psychologically hermetic and sometimes politically simplistic works.

If Snow’s Surrealistic images and ransom-note blocks of text are borne from a style of collage-making invented by the Berlin Dadaists after World War I, conflated with a nostalgia for 1960’s rebellion and edged with 1970’s nihilism and despair, the resulting work is a stubbornly contemporary emblem evoking a fractious, uneasy but resolute us-versus-them attitude gathering in the face of certain catastrophe.

It’s curious that Snow, who was born in 1981, has had no firsthand experience with the countercultural movements he’s invoking. Yet those movements hit a chord that resonates in our current climate, as did the more remote Dadaists. A fifteen-year-old kid filling his iPod with Jimi Hendrix, the Doors and Frank Zappa—the anthems of the peaceniks and Yippies at the height of the Vietnam War—gives you a better read on the mood of the country than anything you can find in the Times. A past style is successfully revived only when it teaches us more about ourselves than we can learn on our own. Thus the galvanic response when Michelangelo first encountered the Laocoön, or when Jacques-Louis David discovered Pompeii, or, for that matter, when Bob Dylan first heard Woody Guthrie. Moving ahead doesn’t necessarily imply moving forward.