- Source: Art in America

- Author: Larissa Pham

- Date: March 01, 2019

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Sense of Style

Eric N. Mack

In an interview with Modern Painters, Eric N. Mack described “Misa Hylton-Brim,” his 2018 solo show at Simon Lee Gallery in London, as an outfit: “a diaphanous dress paired with a supportive combat boot.” Hylton-Brim, the stylist who put together iconic looks for rappers Missy Elliott and Lil’ Kim, is widely considered to be responsible for the eclectic, futuristic, Versace-influenced hip-hop style of the 1990s. Mack’s homage to her reflects his interest in styling and fashion, a preoccupation that guides much of his work. Though Mack describes himself as a painter, his primary medium is fabric. One might say he works in the tradition of Robert Rauschenberg, who expanded painting’s formal range to include collage and experiments with textiles, or Sam Gilliam, who paints on lengths of unstretched canvas. Working with polyester-cotton–blend moving blankets, delicate sheets of silk and organza, thrift-store garments, and found scraps of denim, cotton, and leather, Mack sews pieces together to produce unexpected compositions and configurations. Some works, hung on the wall, echo the rectangular shape of a traditional canvas, while others—draped, stretched, and flexed on wires—refer to traditions of sculpture or installation. But perhaps his most important mode of working is selection: combining fabrics and items to create a specific “look” from an existing material lexicon—the artist as stylist.

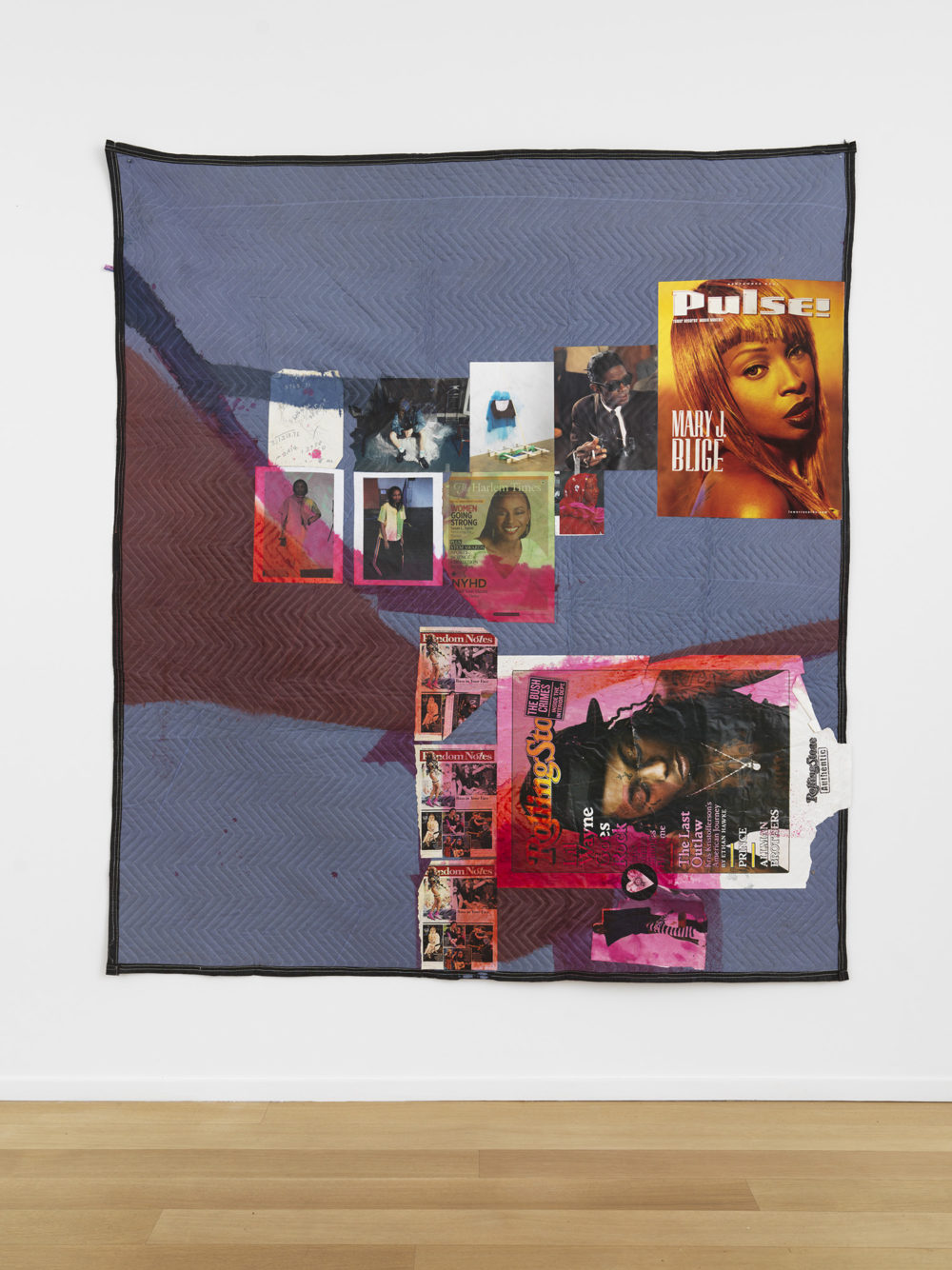

The “combat boot” in “Misa Hylton-Brim” was the moving blanket, the sturdy, quilted fabric designed to protect furniture from damage in transit. Mack used several of these as supports for collages of magazine clippings and other printed matter. The blankets that Mack uses can arguably be called paintings, in that they are stained with fabric dye in patches and streaks. On one such work, (Menagerie) The Thorn / The Veil / The Face of Grace (2018), two icons of ’90s rap and R&B make an appearance: a glowing Mary J. Blige gazes from the cover of Pulse, and a Rolling Stone cover featuring Lil Wayne has been rotated a quarter-turn and splashed with red dye. Paired with a cover of the Harlem Times, featuring Essence editor-in-chief Susan L. Taylor with the cover line “Women Going Strong,” the collection of portraits—all famous black creatives—lends the piece a sense of sparkling confidence and pride, though the work’s title, in its use of “menagerie,” also ambivalently speaks to the way that the work of black artists is often tokenized in its consumption by white audiences.

Eric N. Mack: (Menagerie) The Thorn / The Veil / The Face of Grace, 2018, dye and paper on moving blanket, 72 1/8 by 68 inches. Photo Matt Grubb. Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, New York and London.

Another moving blanket painting, The Brazen Image / The Thief of Sleep (2018)features a spread of runway looks. The models are photographed mid-stride, an array of glamorous automatons. In that same piece, also streaked with red dye, a New York Post cover screams bloody lies! The headline is from a 2010 story about supermodel Naomi Campbell, who denied knowingly receiving a gift of blood diamonds from Liberian president Charles Taylor. Elsewhere on the blanket’s surface, a photojournalistic portrait of a black man, captioned sheer terror, is paired with a black-and-white photograph of a black person in indigenous makeup and jewelry, like a classic National Geographic shot. The juxtapositions highlight the reductive mode in which the media so often depicts blackness. The mood generated here is less celebratory, more sinister: pairings of beauty and terror, beauty and deceit. In these moving blanket collages, Mack seems to ask: With all these images saturating the visual environment, how are black people allowed to be? What restrictive narratives must be transcended? What can be celebrated? United on the blankets under layers of dye, the collages seem less adhered than embedded—as though Mack were describing something not merely superficial but in fact deeply rooted.

While the image on a stretched canvas seems to float in space, Mack’s work has weight and wear to it. You could take one of his blanket paintings off the wall and wrap it around your shoulders. The materiality of the work is emphasized by the imperfect, not-quite-square shape of the thick textiles and their still-visible chevron-patterned stitching. Mack cites Robert Morris as an influence, especially his felt sculptures, which turn flat pieces into three-dimensional forms that come off the wall in slices, folds, and drapes. Morris’s influence is apparent in Mack’s paintings such as The Brazen Image / The Thief of Sleep, where the work extends from the wall to the floor. In Wide Necklace (2017), included in a 2017 group show at Simon Lee’s New York outpost, Morris’s influence is even more obvious. A horizontal strip of fabric with a large gingham print in yellow and beige serves as the back “collar” for the wall-size titular necklace. A kimono-shape patchwork of brick red, seafoam green, and black-and-white striped fabric hangs from the horizontal strip, attached only by its upper left and right corners, the center sagging to form an opening. The rest of the fabric trails onto the floor. The work’s shape suggests both a statement necklace and a human form with arms outstretched, perhaps in crucifixion. Its construction evokes colorful handmade garments, yet the way it hangs is uneasily tense. The slash of the neckline and the way the piece reaches into the viewer’s space recall Morris’s work, but Mack, through his choice of patterns and bright colors, conjures a figure with personality. Wide Necklace is a metonym. It represents both jewelry and the resting dancer who wears it. Where the uniform felt of Morris’s sculptures emphasizes their symmetry, Mack’s work feels highly specific, encoded and personal. His pieces are less an experiment in form than an attempt to tell a story or convey a mood.

I MET MACK as he was installing “Lemme walk across the room,” his solo exhibition currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum. Wearing a boxy, distinctively patterned outfit that looked to be directly in dialogue with his paintings, the thirty-one-year-old artist was soft-spoken and slightly under the weather, but eager to talk shop. “Fabric is so known,” he said. Everyone has immediate associations with a set of scrubs or a ball gown. Meaning can be found in the heft and weave of a textile as well as its mass-produced (or bespoke) print. In Implied Reebok or Desire for the Northeast Groover (2016), the logo on an inverted Reebok windbreaker is recognizable but disorienting at first glance, like text seen in a mirror; layered with a crystal dragon appliqué, a humble pair of checkered kitchen pants acquire a glitzy club look. Mack wants to keep his work democratic, and so prefers to use magazines, streetwear, and pop culture as his reference material, speaking especially to viewers who understand, appreciate, and perhaps even formed their identities within black American culture. He consistently explores how we build our sense of self within given systems through our choices of music and clothing.

In contrast to the heavier “combat boot” moving blanket paintings in “Misa Hylton-Brim,” sheets of semitransparent fabric were draped and stretched in the gallery’s open spaces. They were the other half of the look, the diaphanous gown Mack envisioned. In Blue Duet I (2018), two blue panels ripple at the seam that binds them. The difference in the weights of the two elements creates the impression of movement in a still object, as if the wind were caught in these kitelike shapes. The show’s pleasing polarity opposed delicate and tough, extending an ongoing inquiry into textiles and their character. As a student at Cooper Union, Mack realized that the mechanism of painting can easily be perverted, and through his MFA studies at Yale, he explored the question of painting’s materials. Instead of the cotton duck canvas most commonly used by his peers, he worked with linen, silk, and jute. Each substrate, Mack understood, related differently to what was placed on its surface. From there, the possibilities spun out: why not use patterns? Why not repurpose garments and explore all kinds of fabrics? “I was always surprised by painting,” Mack said, a note of awe in his voice. “I think I still am.” Mack’s exploration of painting takes two straightforward components of the medium—the flat surface, the use of color—and replaces the standard materials, eliminating any resemblance to traditional painting while continuing to grapple with its questions.

Eric N. Mack, Blue Duet II, 2018, Polyester and silk organza, 98.12 x 107.87 x 112.12 inches. Photo Matt Grubb. Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, New York and London.

For “Lemme walk across the room,” Mack has chosen an installation approach that directly engages the site’s architecture. Mack’s upbringing has shaped his interest in art’s relationship to space and surroundings: his father worked as a display expert at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The young Mack grew up not only surrounded by art but with the behind-the-scenes knowledge that its presentation, too, is a craft, from the construction of a vitrine to the color choice of a background. In Mack’s latest show, one long, gauzy strip of white fabric, intersected by another, shorter one divides the Brooklyn Museum’s Great Hall with an X. The two long sheets are streaked in a red, green, and black tartan pattern by large paper cards that were soaked in dye and dragged across their surfaces, creating a stroke reminiscent of a giant fabric marker. Above, a slowly oscillating wall-mounted fan makes the fabric gently ripple. This diagonal barrier has the effect of occluding the exhibition’s introductory wall text. In order to read about the show, visitors must walk, counterintuitively, between the sheet of fabric and the wall toward a dead-end corner where the two long sheets intersect. This narrow passageway creates a zone apart from the work: the institutional text is blocked off from the installation, suggesting that Mack intends visitors to develop their own interpretation. “Lemme walk across the room,” Mack explained, is “more of a closet,” as compared to the outfit of “Misa Hylton-Brim.” He listed its components: “Some jewelry, a jumpsuit. A pair of shoes. And definitely a hat with a brim.” Indeed, at the center of the show, a white cowboy hat dangles off the edge of a pipe, above an inside-out red-and-orange plaid bedskirt, which spills across the ground like the ruffled hem of a woman’s evening gown. The sculpture, resting on the armature of a metal stepladder, also features a crumpled metal chain-link fence, bent and warped to resemble the undulation of water. Titled The opposite of the pedestal is the grave (2017), the piece looks both barbed and costumed, conjuring the ping-pong between conditions—life and death, elevation and failure—that the title implies. The cowboy hat lends the sculpture a playful posture, like a performer taking a bow, and the skirt has a kind of regal yet folksy grace. But the sharp edges of the crushed metal fence give the ensemble the spiky double valence that characterizes much of Mack’s work. A stepladder may take one up to greater heights, but a height is still a place to fall from.

One wall in the Great Hall features a large collage on oilcloth, less textured than Mack’s moving blanket pieces but with a similar mix of magazine clippings worked over with streaks of fabric dye. Kelis poses on the cover of the Fader, while Courtney Love (styled to look like Marilyn Monroe), Janet Jackson, and an advertisement for the West African airline Afrik Air also make appearances. The airline ad is a reminder of the distance that separates immigrants from their home countries and families, but it also serves as a symbol of how ideas and images travel; together, the set of references conjures the experience of identity formation, of mixing and meshing cultures to find a personal style. On another wall, sheets of paper hung salon-style, edges curled from dye, offer a new element to Mack’s work, and are the artist’s most traditionally painterly pieces. The paper cards, colored and streaked with gradients, were used to dye the tartan-patterned fabric divider. They are the byproducts of making the work. In an installation, they feel slightly unfinished: while the upturned edges speak to Mack’s interest in punctuating space with form, the cards as a whole offer little more than color. Nevertheless, they suggest a compelling direction for Mack. One wonders what other artifacts of his process could be put on display, and how.

As a closet, rather than an outfit, “Lemme walk across the room” feels like the beginning of something new. It’s an array of Mack’s tools, a dressing room with clothes and jewelry laid out, displaying what the young artist can do, and indicating that more is to come. Mack collaborated with fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner in 2018 to create a backdrop for her London Fashion Week men’s show, and when we spoke, he mused on how his work at the Brooklyn Museum could similarly function as a set for a party or other gathering, bringing club vibes to the space and transforming the museum. He envisioned a live performance that could be recorded and played back through the show’s duration, adding another dimension of experience to the work—a fitting choice for an artist who works with layers of material and cultural meaning.

Eric N. Mack, Untitled, 2018, Cotton, denim, dye, linen, polyester, and silk, 98.12 x 113 x 112.12 inches. Photo Matt Grubb. Courtesy Simon Lee Gallery, New York and London.