She Did It

Cajsa Von Zeipel

by Will Perkins

When given the opportunity, the leg room to reflect can burden the procrastinate soul to ruin. Put-off concerns clench and release, stumble into each other and clumsily spill over. In the wake of a crisis, while you struggle to hold onto a life both slipping and standing still, a leap of faith and the adrenaline of arrogance assumes you might make time for me.

I came into Cajsa’s orbit by chance encounter, popping in and out of the Roosevelt hotel’s rooms turned pop-up galleries at the Felix Art Fair. Like an after-hours fling, Cajsa was waiting in room 1105.

Fig. 1

Her gallerist, Taylor, was there to greet me. Taylor and I go back a bit. She has a dog, Misty. Misty is about the size of a cat. She has a dark hairless body with light spots spread all over, wears fur boots for paws, a long bushy tail and messy bangs. Her unmistakably camp sensibility is accentuated by her dangling tongue, conspicuously propped to the side of her mouth like a long drool just about to pop but never does. If John Galliano took a shit before a show, Misty would crawl out the bowl.

Taylor has a husband, Will. Will is a painter and tattoo artist. I have two tattoos by Will but only one “Sheldon.” Sheldon is Will’s last name and a “Sheldon” tattoo reproduces the abject, puckish psychedelia that show up in Will’s paintings; spindly crypt keepers, ghastly skulls, tear glinting eyes, dismembered body parts, wilting trees and flowers, all stirred up into a sensuous drama of macabre euphoria. On wall or in skin, dispossessed of ego, they affect and effect in the cinematic agonizing of the Baroque; They beguile you into suspended belief of a grotesque reality, disrupt the scene and fight for attention wherever they show up.

Taylor and Will came into my life because of their best friend Jessi. Jessi and I used to date for about two years, now about two years ago. As a best friend, Jessi is a bleeding heart. One time, at the opening for Will’s show at White Columns, she suddenly broke down into tears overwhelmed by the joy of being surrounded by a room full of his paintings. Like spilled cream, I heard the alarm before I saw it, looked up and rushed her into my arms. Struggling to turn her face away from my chest, she smiled and muttered silently, “He did it.”

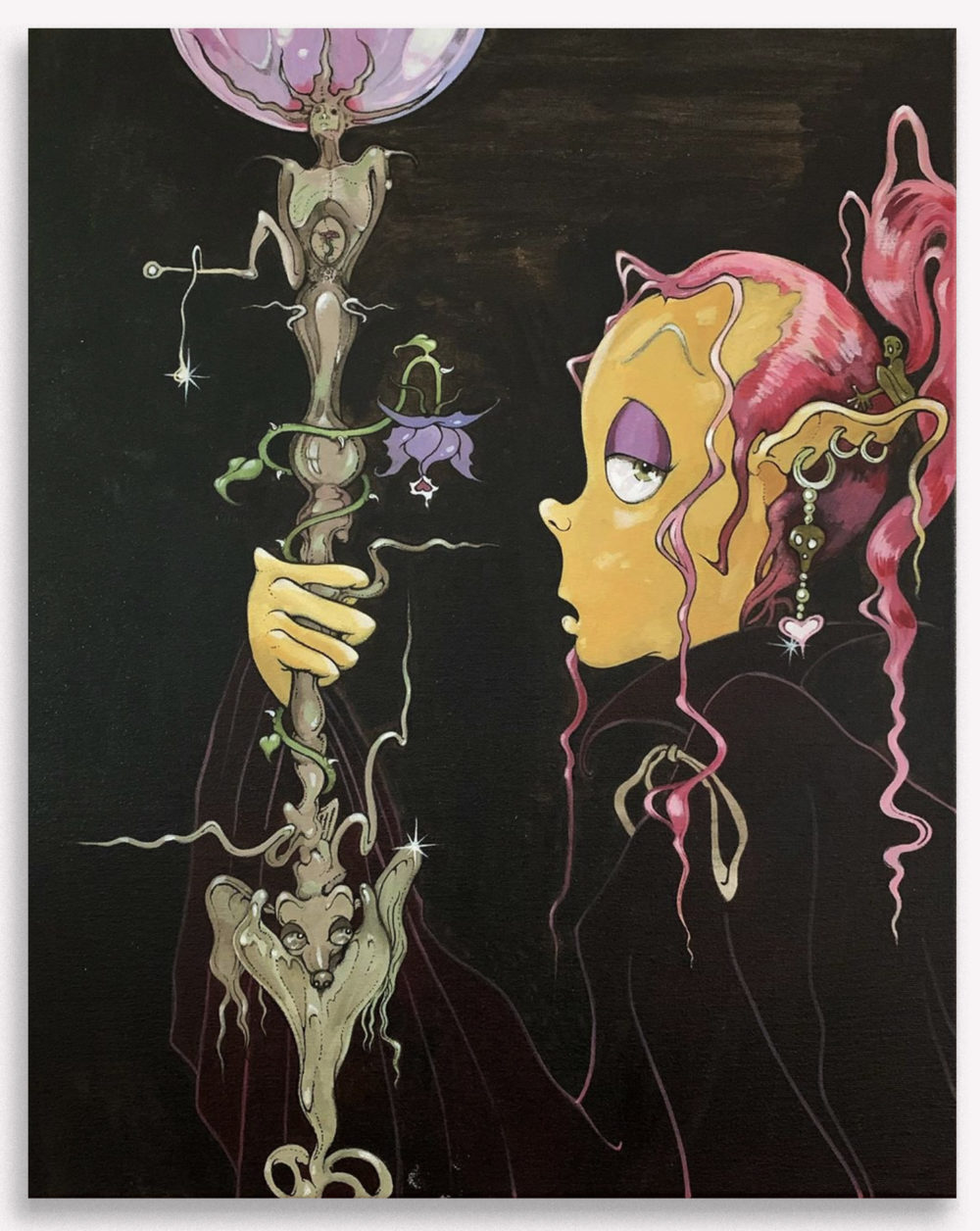

Fig. 2

As an artist, Jessi is a sculptor. From trash and found objects, she creates preposterous assemblages that disembody tropes of modernist design and sweat out ruminations on function and dysfunction. In their presence, the world you used to know brought to its knees. In this new world, bewilderment and haunting arouse anxious curiosity. Here, tumbling dust bowls gather fragments of the past: glass, sawdust, polyester, rubber, metal, graphic t-shirts and driftwood.

Against their will, these sculptures have contorted into freak plot-twists that resemble furniture – function – but destabilize corporeality – dysfunction -. You take a seat on “Blue Heart Shelf” (2019), wipe the dust from your eyes and rest your chin into the palm of your hand. Staring blankly over the horizon, you contemplate a wasteland of voided formalisms gasping to reclaim their inner life.

Jessi and I would eventually fall in love. Though, through no fault of her own, I would repay her by packing up and moving across the country. Before all that could happen, Jessi had to find me the way most women had; preoccupied with ambition, helplessly selfish, damp with the stench of past lovers, slipping down the promise of the unknown. Of options that come up short. Willfully tossing my bucket down the busted drinking well of single life in New York City.

Jessi found me not entirely unlike I find myself these days. Fifty days or so to be sure. Alone, with far less options, mostly my thoughts to keep me company, trying to make sense of my motivations.

Fig. 3

I imagine past and present lovers in a police lineup and attempt to identify cause and effect. What was it about this one that filled me with so much joy the next morning when I opened my eyes to see her still lying in bed next to me? What unmet, most likely, unspoken desire made me dread the thought of ever seeing that one again? Who made me feel safe?

In another moment, I see myself as a child sneaking into my father’s dresser drawer to discover the diary he never kept. I thumb through it to find an entry that explains why I had to bear witness to the infidelities against my mother. How when he and so and so would go in the bedroom to “talk”, they could hear me turn up the volume on her TV to shelter my imagination from reality.

Before he can catch me, I nervously slam the diary closed and emerge in front of my laptop, taunted by the flashing cursor of an empty page. In the back of my mind I hear footsteps of lurking ideas inch closer and closer only to make inspiration appear by shifting it someplace else.

And on and on in this way.

Like a prisoner, I walk around my apartment in circles confined to reflection, negotiating with ghosts of the past and a hypothetical future. Reckoning with the self-indulgent decadence of isolation.

But back to Cajsa. Between hope and hopelessness and somewhere between the news and @Patiasfantasyworld, the memory of Cajsa’s “Fluff You, You Fluffin Fluff” (2020) teases my boredom into a kinky mirage. “Fluff You” is a figurative sculpture imagined in the uncanny image of the artist herself. This is true of all of Cajsa’s sculptures, made of silicone and mixed media, brought to life through some combination of her own body, the body parts of friends and admirers, male and female. The effect creates a decentered experience of the body, one that refuses to abide by sexual hierarchy arriving both gendered and genderless.

“Fluff You”, with its large breast reads as a “she.” She’s hot. She looks like a rejected, Amazonian techno princess from the future sent back in time. Spat out, her clothes are phlegmy and wet; a holey pompadour pink blouse, lavender tights, and violet platform jelly shoes. The two-filter mask she wears as a hat, cocked upside down above her forehead, puts on that this is a self-portrait of Cajsa who we can imagine wearing personal protective equipment while in the studio to safeguard her own life as she breathes life into her others.

Cajsa is sitting atop a globulus apparatus that suggests a sort of post-apocalyptic Segway, molded from aborted relics of industry from a time she never knew. What we can make out: a wheel of a stroller, exhaust pipes sticking out at odd angles, exposed wires connecting to her platform jelly shoes, a kitsch dreamcatcher hanging from the window shield like a navigational device, its center weave held together by zip ties, its feathers replaced by fishing lure, macaroons, chains and metal carabiners.

An iPhone mounted to the windshield displays a lenticular photo of a topless woman. Seen at one angle the woman, a brunette, lies on her back seductively gazing at the camera. Seen from another, she playfully models a cowboy hat. The intimacy of these portraits might imply a significant other, one she fell in love with and left behind or come back to reclaim.

Cajsa’s body is set in motion, her torso slightly twisting away from the iPhone calling up Michaelangelo’s painting of a Sibyl, a figure from Greek mythology who foresaw the future. Adding to the contrapposto effect, two stuffed puppies peek their head out from her pant and blouse. Their facial expressions match Cajsa’s: open-mouthed, dejected and longing, begging to be fondled. Set between her ass and breast, the sexual orientation stresses the urgent desire of the figure and confirms her relationship to the women in the photo. It is a lover. And what we’re witnessing, perhaps, is Cajsa agitated to ecstasy, overcome by lust and yearning caught up in a wet dream.

Fig. 4

Like a Sibyl, Cajsa’s gas mask, iPhone, and macaroons – safety, community and nourishment – emerge somewhat prophetic, anticipating our basic needs. In her image we discover a stand-in for our own:

A. Bodies transformed into hyperbolic containers that shift through various states of collapse and reconfiguration.

B. Bodies overworked by seemingly irrational conditions under which systems, things, sense and knowledge have broken down and stopped working.

C. Bodies in Heat.

Even still, the pursuit of happiness can continue, reframed having had all its complications removed. Pleasure without consequence, beauty without judgement, inspiration without realization, praise without jealousy, nudity without modesty. Raw passion, without boundaries.

No doubt, no guilt, no hesitation.

To say nothing of love. For now, only passed along artificially, like fluff. Tempting desperate bodies stuck inside all of the world, full of cum, bursting at the seams for the real thing.

Figure 1: Cajsa Von Zeipel, Fluff You, You Fluffin Fluff, 2020, Mixed media and silicone, 72 x 52 x 40 inches (190.5 x 132.1 x 101.6 cm). Image courtesy of the Artist and Company Gallery, NY

Figure 2: Will Sheldon, 🧚♂️🦇🧘♂️💀🔮, 2020, Acrylic on Canvas, 20 x 16 inches (50.8 x 40.6 cm). Image courtesy of the Artist

Figure 3: Jessi Reaves, Blue heart shelf, 2019. Wood and metal chairs, woven fabric, plexiglass, paint, plastic, sawdust, wood glue. 96 × 21 × 30 inches (243.84 × 53.34 × 76.20 cm). Photograph by Greg Carideo. Copyright Jessi Reaves. Image courtesy of the Artist and Bridget Donahue, NYC

Figure 4: Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Libyan Sibyl, C.1511. Creative Commons License.

Will Perkins is a Creative Director and Writer who holds an MFA from Parsons School of Design. His writing has been featured in Franchise and Office Magazine.