Can it be that it was all so simple then

By Bonnie Clearwater

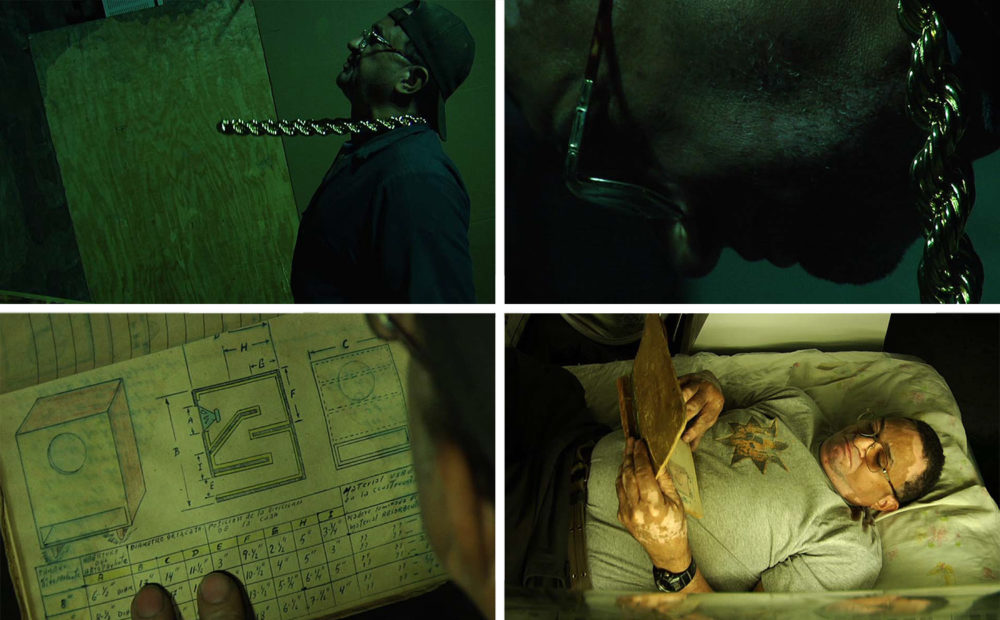

Let’s follow Luis Gispert. He has recently premiered a new film called Rene. Shot in the genre of neorealism as a three-channel synchronized film, Rene records the daily routine of Rene, an old family friend of the filmmaker. Rene fled Cuba to Miami and works in a restaurant supply shop in downtown Miami, repairing machinery. The film has no narrative, but the arc of Rene’s daily activities—waking, eating, working, and sleeping—establishes the film’s structure. How real is real? Although Gispert filmed his subject over the course of several days, he edited hours of footage to a running time of approximately fifteen minutes. The camera always seems to frame its subject to heighten the drama, intensity, and even strangeness of the scene. Each activity is filmed from a different vantage point that is projected on the three screens in the installation. Rather than being drawn into the film, the viewer becomes part of the three-dimensional space of the installation. As the film progresses, the viewer starts piecing together an impression of Rene. He lives in Spartan surroundings. In a sequence documenting Rene as he repairs a sausage-making machine, Gispert films the scene so that the gleaming, automated metal is transformed into a highly polished, fetishized sculpture. In another sequence, Rene is shown flipping through sketchbooks, displaying drawings of a variety of antiquated sound systems. We assume from the film that these are Rene’s drawings. Rene holds the sketchbook at an angle that suggests he is showing it to someone, yet in all the sequences Rene is filmed alone. No one else occupies the frame. But Rene is not alone, as Gispert and his camera are ever present. This show-and-tell also acknowledges the unseen audience who will glance at the sketches and share this glimpse into the creative life of Rene.

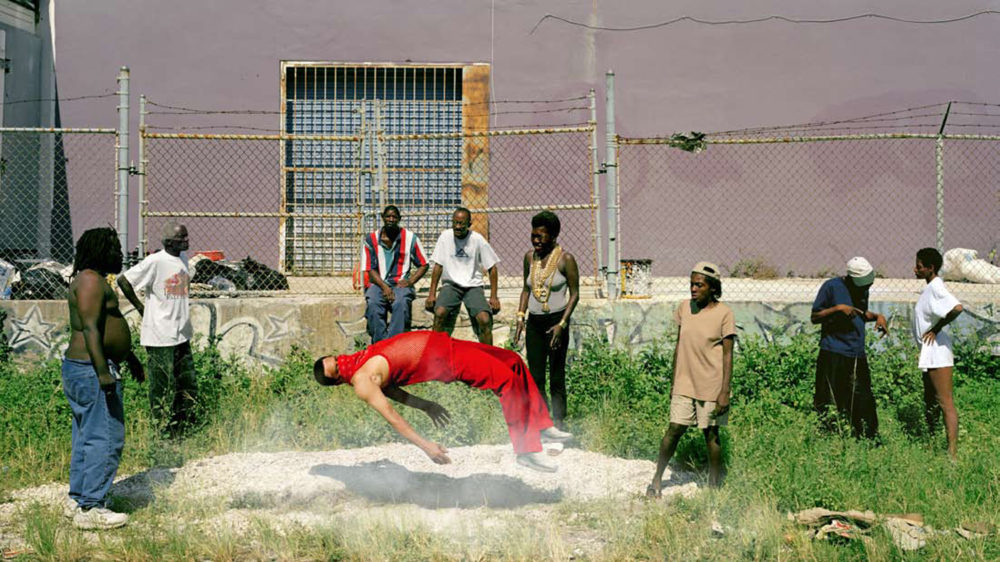

Gispert calls his film an intimate portrait, but it is easy to become suspicious of its veracity. Rene can levitate, as he demonstrates by ascending on a machine that raises his prostrate body. The chain around his neck also seems to float like magic in midair. Gispert says Rene is not acting in this film, that he is so comfortable in front of the camera that he can be completely natural. Still, questions arise regarding the action and the props. Did Gispert or Rene decide to flip through the sketchbook? Why would Rene demonstrate the special effect of levitation as part of his daily routine? Does he really live as austere a life as represented in the film? Rene, in fact, has long been a willing and versatile subject in Gispert’s work. In the photograph Untitled (Grave), 2005, he wears red athletic clothes and a red bandana over his nose and mouth as he levitates above the street. The character in this photograph is at odds with Rene’s pose as a dapper gentleman in the photograph Turntables, 2003. Gispert provides insight into his motivation for this film: “When I called the film a ‘portrait,’ I wasn’t thinking of it as a literal photographic portrait. It is an interpretation of Rene. Rene has always been a subject and collaborator, perhaps not much different from the relationship between Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski. I’ve woven Rene’s real-life narratives with scenarios of my own, many times arriving at said scenarios with Rene’s input.” When he conceived Rene, Gispert aimed to “subdue the craft of filmmaking,” especially that of “widescreen narrative cinema.” However, he explains, “In the end, Rene is just as visually stylized but in a different manner. These are just surface formal concerns. What interests me is the psychological space of my relationship to the subject.” Rene marks a move away from the widescreen impact of his films Stereomongrel and Smother, which preceded it. To some extent, Rene is linked to Gispert’s first videos. Gispert recently noted, “My earliest videos consisted of simple, single concepts executed with modest technical proficiency. Spoken language was usually omitted and musical or ambient sound was used to create a more democratic atmosphere for the work, which allows the videos to have a universal read not bound by language.” These early video works are raw and aggressive and deliberately contradict film conventions. The soundtrack plays an essential role in establishing the rhythm of the images and action. In Pony Show, the soundtrack is a 1980s pirate radio transmission by Miami-based disk jockey Jam Pony, which Gispert recorded off the radio while still in junior high school. The video is a simple slide show of images that could have been drawn from a family album. Whenever the DJ interrupts the song, the image goes black. The soundtrack also provides the structure in a number of Gispert’s subsequent videos. In Block Watching, the cheerleader’s movement is dictated by the screeching cadence of a car alarm, to which she is lip-synching; the cheerleader in the sentimentally titled Can it be that it was all so simple then seems demonically possessed by the powerful rap lyrics she is mouthing (the title and lyrics are taken from the seminal 1996 hip hop record 36 Chambers by the Wu-Tang Clan).

Fig. 1

Previous critical analyses of Gispert’s work have focused primarily on the multicultural and hip hop imagery in his work. Consequently his work has been perceived as a means for the artist to address the various subcultures that infiltrate the mainstream. In retrospect, the works of the last decade reveal more about Gispert and his desire to achieve a psychological romanticism than they tell about marginalized subcultures. They are the summation of a variety of youthful experiences that provided the impetus for his ambitions as an artist. As a teenager, Gispert was involved in making sound systems and customizing cars, participating in a subculture in which the customers, mostly men, aspired to establish their individuality by modifying mass-produced objects. This task required him to make aesthetic decisions long before he was aware of art history or what constitutes an art work. For his earliest sculptures, he tapped into this experience, creating highly customized race carts that were so extreme they were not functional as vehicles. Essentially, customized cars are big toys for adults; they extend childhood memories of the excitement of racing soap-box cars. Gispert’s aim for his work is a retrieval of the visceral, acoustical, and psychological impact of the widescreen CinemaScope films and the neorealist and surreal films of Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, and Michelangelo Antonioni, as well as the science-fiction and body-horror films of David Cronenberg and John Carpenter, which impressed him as a youth. He is driven to create work that lives up to the cinematic sublime.

Art history is Gispert’s source for a collective memory. The art of the past provides conventions, sensations, and expectations for the creation of new work. At the beginning of his career, he turned to artistic traditions that exalted the hero and the divine. The intense, ecstatic experience of CinemaScope movies is rooted in the theatricality of Baroque paintings. With their lush coloration, foreshortened and contorted figures, and elaborate details, Baroque paintings are a whirl of dynamic movement frozen for eternity. Saintly figures ascend to heaven, as putti float among the clouds. Gispert spent a summer during graduate school photographing Baroque paintings during a visit to Europe. This image bank served as an essential resource for his first major photographic series, the cheerleaders. Although in contemporary uniforms and ornamented with the heavy gold chains and charms associated with hip hop culture, the cheerleaders assume poses that are reminiscent of figures in Baroque allegorical paintings.

Prior to the cheerleader series, Gispert experimented with trying to photograph an airborne figure, as seen in Goalie. The mass media has transformed professional athletes into heroes of mythic proportions. Typically, sports photographers capture athletes in midair to produce dynamic action and create an image of superhuman strength. Using the fast camera employed by sports photographers, Gispert had his model leap approximately 100 times until he caught the perfect iconic moment.

Fig. 2

The cheerleader photographs build on the image of Goalie, but in these works Gispert resorts to artifice rather than the realism he used in the photograph of the leaping goalie. The compositions are staged in a studio rather than in situ. These photographs were achieved with cinematic techniques and methods to produce special effects, most notably the green-screen. Gispert used a long exposure to photograph his models suspended on wires in a chroma-key room. In movies, actors play against the green background, which is typically superimposed onto another backdrop to complete the illusion. Gispert, however, retained the green field to reveal the artifice and create a perfect void. Although the models were suspended by wire, the acrobatics typically performed by cheerleaders makes these scenes plausible enough that viewers are willing to suspend their disbelief. These photographs are seductive in their use of lush coloration and athletic models, and aggressive in their use of effusive gold chains and charms to reference hip hop and gang culture.

Fig. 3

The cheerleader photographs led Gispert to create more elaborate scenes in his Urban Myths series, in which he turned the camera on his family to create tableaux based on stories he remembered from childhood or experiences and sensations he felt as a youth. The interior settings are the actual homes of his relatives; the décor is unaltered. Although the environment is authentic, Gispert staged the poses of the figures, all family members or close family friends, after Baroque allegorical paintings (as in the cheerleader series). The photographs, shot with a large-format camera, capture every detail with a clarity that produces a heightened sense of reality. Into this realm Gispert introduced elements of the supernatural, such as levitating boom boxes and ghostly children, with the aid of special effects and digital manipulation.

In Untitled (Living Room), 2003, Gispert posed his grandmother as an eighteenth-century Spanish maja right out of a Goya painting. Two little girls, meanwhile, create mayhem by jumping up and down in the formal living room. The scene is a humorous response to the way this formal room was off-limits to the family, especially children. Like a museum vitrine, family members were able to peer into this room but not actually occupy it. Upon closer inspection of the scene, it becomes obvious that the children are not actually in the room. Rather, Gispert added the rambunctious girls with digital modification. Nearly transparent, the girl on the right appears as a blithe spirit disrupting the sanctity of the room.

Several vintage boom boxes orbit around the central figures in Turntable (the man in the tan vest and pants is Rene). During the shoot, assistants held the turntables in place; Gispert digitally made the assistants disappear, so that only the turntables remain floating in space. The bird’s-eye view suggests that the photographer himself was levitating above the scene (images of birds, in fact, abound in the room’s decor). Gispert reveals that he has a large collection of turntables and boom boxes and that, for him, they represent a longing for innocence and for the early days of hip hop. He has also come to see them as a force for creativity and as his own surrogate. This photograph provides some clues as to why he would choose Rene as his first subject for a film portrait. It turns out that the sound systems shown in the sketchbook Rene displays in the film were his own designs for equipment he built from spare parts in Cuba. Rene’s creative past was part of family mythology, and he clearly was an inspiration for Gispert during his childhood. In Turntables, Rene is at the center of the scene and, in a sense, at the center of Gispert’s universe.

Fig. 4

The Urban Myths series wistfully captures a cultural past that is disappearing as subsequent generations of Gispert’s immigrant family assimilate in the U.S. In these photographs, the artist preserves his family’s homes and surrounds each subject with attributes representing luxury and success. The younger generation appears as simultaneously present and absent or floating above the scene.

Gispert’s family photographs in the Urban Myths series led him to make his first major film, Stereomongrel, 2005, which he produced in collaboration with Jeff Reed. Although there is a suggestion of a narrative—as the young protagonist unleashes her superhuman powers and enters a hyperreal world after her birthday celebration is dashed by the absence of her father—the film is composed of sequences of unforgettable, fragmented moments. Cheerleaders adorned in hip hop regalia come to life in Stereomongrel. They, along with the giant boom box, are a source for the film’s enchantment and mystery. As in the earlier cheerleader photographs, the figures levitate and fly. In one sequence, the girl wanders through the Whitney Museum of American Art galleries, where works from the museum’s collection of contemporary art are displayed. Like the real domestic environments of the Urban Myths photographs, the contemporary art galleries become a ready-made stage set and provide the props for the events that unfold. None of the works hanging in the galleries are by Latin American artists, making the filmmaker’s presence as exotic as the bare-chested indigenous-Latin American security guard singing a 1940s Cuban ballad by Beny More among the American paintings and sculptures.

Fig. 5

During the filming of Stereomongrel, Gispert turned to creating photographs of the “real” world that he imagined existed outside of the film’s world. He contrasted the gritty but glamorous New York City with desolate and blighted areas of Miami. The settings of such photographs as BB Matrix, 2004, and Untitled (Grave), 2004, are unaltered sites, but the action is staged. In BB Matrix, the barren landscape dwarfs the figures, as in traditional Chinese landscape painting. Gispert quartered the composition, placing a flatbed truck filled with boom boxes at the crossroads. The truck is a magnet for area youth, who carry off the boom boxes. In the tradition of neorealist film, for Untitled (Grave) Gispert employed non-actors, individuals who actually lived on the streets of downtown Miami. Gispert arranged them in natural poses around the central figure hovering over the ditch. Although the figure’s face is concealed by a red bandana, we recognize him as Rene, performing the special effect of levitation (the mechanics of which he subsequently demonstrates in the film Rene).

Fig. 6

Art history continued to inform the compositions of some of Gispert’s photographs from this time. In Senoritas Suicidio, (2008), naked maidens float as a single cluster in a pool.1 Gispert positioned this scene so that the figures are parallel with the picture plane. As a result, the girls appear to be levitating even though no special effects were used. The scene looks natural and unarranged and yet there is something very familiar about this group of nudes, especially the way one crouches at the right and another holds her arms akimbo. The rippling water distorts the features of their faces, producing mask-like visages. The astute viewer will realize that Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon served as the model for this composition, which looks so natural and real in contrast to the obviously theatrical cheerleader photographs.

After this series of neorealist photographs, Gispert delved once again into experimenting with CinemaScope film, in Smother, 2008. As in Stereomongrel, Smother’s narrative centers on a child, this time a boy, whose complicated relationship with his beautiful, flawed, and obsessive mother leads to a sequence of startling and brutal scenes. The setting alternates between the “narco-nouveau riche mansion,” which had belonged to the boy’s deceased drug-dealing father, and a barren wilderness, where the boy encounters the “bad man.” Technically, Gispert aimed to mimic the optical texture of the sci-fi and horror movies he saw as a youth, especially those by John Carpenter and David Cronenberg. The look of Smother is the Miami of the iconic 1983 film Scarface by Brian de Palma. The film, however, was shot mostly in Los Angeles, which today more closely resembles 1980s Miami. The “bad man” in Smother is played by Steven Bauer who, as a violent gangster in Scarface, terrified Gispert when he saw the movie at age 12. Overall, the laconic pacing is similar to the B-films of the 1980s and the special effects mimic the pre-digital animation of the period. The transformation that occurs at the end of the film, with the boy’s mongrel dog (based on Gispert’s childhood pet) immersed in a pot of boiling liquid, is also typical of the horror films of Gispert’s youth. As Gispert notes, “The expulsion of the boom box from the dog’s chest cavity is a trope taken from sci-fi horror films such as Alien, The Thing, Videodrome, and Invasion of The Body Snatchers, where a foreign entity takes over a body, gestates inside, and ultimately exits through the chest cavity.” Gispert introduced elements of neorealism in Smother, noting:

“The slaughterhouse scene was shot at a real abattoir where I incorporated the actual daily operations into the narrative of the film. The cameras rolled as [the workers] completed their daily quota for slaughtering pigs. I shot this in widescreen CinemaScope, which aestheticized the grizzly act and brought into question the reality of it. I remember reading Orson Welles criticizing Luchino Visconti for over aestheticizing the plight of poor Italian fisherman in La Terra Trema a supposedly neo-realist film. That impulse to aestheticize a banal or repulsive act is something I wrestled with in Smother and Rene.”

Fig. 7

The widescreen grandeur of Smother and Stereomongrel influenced Gispert’s recent photographs of elaborately customized vehicles, taking him back full-circle to his early fetishized sculptures. For this series, he tackled the problem of creating landscape photographs, perhaps the most clichéd genre of the medium. He shot hundreds of sheets of film for each landscape in an attempt to capture the perfect vista, but ultimately digitally composited various details to produce landscapes that most closely matched his ideal. These landscapes, mainly viewed through the front windows of the customized luxury SUVs, military vehicles, and low-riders, provide the viewer a strong physical sensation of actually occupying the driver’s seat. By splicing together sheets of film, Gispert was able to capture an uncanny amount of detail, all of which is in sharp focus. The photograph neither replicates the way the eye sees nor what the camera is capable of capturing. The scale of these photographs is so large that the image’s anomalies are not immediately apparent, as the eye wanders around the composition focusing on smaller sections and fascinating minutiae, such as the tribal procession spied through the tricked-out car in Untitled (Processional Litter), 2007.

Although each of these photographs is presented as a single scene, the viewer could spend considerable time sorting out the various details and puzzling over the locales. History will absolve me, 2008, was shot in an abandoned iron mine in the California desert. The scene is deserted except for the lone dictator, in an antediluvian uniform, playing records like a DJ through an antiquated sound system. Although the title references a famous quote by Fidel Castro, the various elements confound attempts to identify the dictator or the specific period or place that this compelling photograph depicts. Contributing to the confusion is the graffiti in various languages on the walls, and the New York-style block construction housing project that peeks out over the wall.

Fig. 8

Gispert typically starts his projects by posing questions to himself and creating new challenges. This occasionally requires the obliteration of elements of past projects. He marked the end of the cheerleader series by incorporating all the jewelry he used for his props into his sculpture Fucking Fake Flondes. The wooden structure is the logo for the band Black Flag, which was designed by artist Raymond Pettibon. Gispert made this work from the outside in, first curving the words into a cylinder and then building the intricate interior structure. Encrusted in gold, the sculpture suggests a sacred reliquary and continues the allusion to the Baroque religious paintings that served as the inspiration for the cheerleader photographs. The reference to “Fake” in the title underscores the artifice Gispert employed to create the cheerleader photographs.

At the end of the film Smother, Gispert once again symbolically destroys the past in order to make way for a new path to explore: The boy becomes the mongrel, which when pulled from the symbolic baptismal well of the boiling pot of liquid, emits cosmic rays before bursting open to reveal a boom box. Out of destruction comes creativity and a true “stereomongrel” emerges.

Fig. 9

Gispert says his film Rene is a break from his past films and the self-analysis of his earlier work. Yet this three-channel film, projected on three free-standing screens, literally and physically forms a circle with the artist. Rene’s portrait is fleshed out when the mysterious references in the film are connected with the scenes in earlier works, and Rene’s gestures suggest his awareness of the filmmaker’s presence. Although Gispert claims he killed off the boom box with the Smother film, it is resurrected in the drawings of sound systems in the sketchbooks shown in Rene.2 Much as he strives to distance himself from his subject, Gispert creates work that continues to revolve around him as he launches each new series with a new set of problems that only he can resolve.

1. The women in the photograph are porn stars from the internet site “suicide girls.”

2. According to Gispert, “The sketchbook complicates my relationship with Rene. Since his youth he’s been an audiophile and enjoyed fabricating homemade sound systems. Also he had a stint in art school after two tours of duty in the Angolan war for the Cuban army. The sketchbook is the only personal item he smuggled out when he escaped Cuba. There are uncanny parallels between Rene’s 25-year-old sketchbook and mine when I was in art school. In the first 12 years that I’d known Rene, there had been no mention of the sketchbook; its existence was brought to my attention through the extensive conversations we had during the week I filmed his life. Also note that Rene is a great storyteller and I made the conscious decision to turn the camera off when we spoke. What I filmed were the moments in between, which are loaded with the context and narratives of whatever conversation we had. Perhaps my next project with him will be to record his stories and intertwine them with a story of my own. Rene has been a friend, a collaborator, and a muse.”

Figure 1. Luis Gispert, Installation view, MOCA at Goldman Warehouse. René, 2008 Digital video, color, and sound. Photograph by Steven Brooke.

Figure 2. Luis Gispert, Untitled (Hoochy Goddess), 2001, Fujiflex print, 72 x 40 inches (182.88 x 101.6 cm)

Figure 3. Luis Gispert, Goalie, 2000, Fujiflex print, 30 x 50 inches (76.2 x 127 cm)

Figure 4. Luis Gispert, Turntables, 2003, Cibachrome print, 50 x 64 inches (127 x 162.56 cm)

Figure 5. Luis Gispert, Stereomongrel (detail), 2005 (In collaboration with Jeff Reed), Super 35mm film transferred to high definition digital video, 10:00 (looped), Color and sound

Figure 6. Luis Gispert, Untitled (Grave), 2004, C-print, 32 x 56 inches (81.28 x 142.24 cm)

Figure 7. Still from Smother, 2008, DVD, color, and Sound 28:00 (looped)

Figure 8. Luis Gispert, History will absolve me, 2008, C-print, 65 x 120 inches (165.1 x 304.8 cm)

Figure 9. Stills from René, 2008 Digital video, color, and sound

An acclaimed curator and scholar, Bonnie Clearwater has extensive experience as a museum director and arts administrator. She has organized numerous historically important exhibitions for MOCA, North Miami, as well as for such institutions as National Gallery of Art and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, among others. She has written extensively on Modern and Contemporary Art and is author of titles including The Rothko Book (Tate/Abrams, 2006). Clearwater holds an M.A. in Art History from Columbia University and a B.A. in Art History from New York University.

©2009 Bonnie Clearwater, published in Luis Gispert, 2009