- Source: HYPERALLERGIC

- Author: PATTY GONE

- Date: OCTOBER 01, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Science-Fiction Dreams Rendered in Three Dimensions

Room for Living, Jacolby Satterwhite’s first museum exhibition, draws together a decade of mind-melting speed while also marking a change: he’s learning to use sculpture to stand still.

Jacolby Satterwhite, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, “Room for Levitating Beds” (2019) PLA filament, epoxy, epoxy resin, spray mount, aluminized glass beads, HD color video, steel, velour, plywood, vinyl, hot glue, foam tubing, wire, and poly-fil; 48 x 120 x 48 inches

PHILADELPHIA — A flying machine flanked by winged horses soars over glaciers and flooded deltas. Like all great sci-fi objects, it strikes a balance between future and fantastical past, powered by nude men marching on a conveyer belt, spewing fire, and traveling faster than any present-day commercial jet. Jacolby Satterwhite doesn’t abide by contemporary rules of space and time. In “Blessed Avenue” (all works 2019), he leaps from Philly to Louisiana, from live action to animation, from sex party to Shanghai noodle bar in a single jump cut. Since almost a decade ago Satterwhite taught himself Maya — a 3D animation program that allows him to import video of himself and others into any landscape, any room — he hasn’t stopped moving. Or maybe his pace began before that.

All futures worship speed. Captain Kirk accelerated to warp, Blade Runner’s cars careen around skyscrapers, and even Tommaso Marinetti and his cohort got the idea for Futurism when “Suddenly … huge double decker trams … went leaping by.” Even as he conducts a tour for me and other journalists of his show at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, Satterwhite glides us piece to piece, rattling off influences and anecdotes: Bruce Nauman, Final Fantasy, Carvaggio. But Room for Living, his first museum exhibition, draws together a decade of mind-melting speed while also marking a change: He’s learning to stand still.

Jacolby Satterwhite, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, “Room For Demoiselle Two” (2019) 60 x 45 inches

The museum’s second floor houses Satterwhite’s collaborations with the Fabric Workshop and Museum. As part of his two-year residence, he worked with FWM’s full-time artist employees to expand his practice to static objects. For instance, “Room for Doubt” reimagines Carvaggio’s 1603 painting, “The Incredulity of St. Thomas,” in which the famous non-believer dips a finger into Christ’s wound. In Satterwhite’s version, four life-size nudes mimic the poses of Jesus and company, their torsos containing small screens showing a performance in which Satterwhite grimaces as he drags his body across a floor. There’s no messiah or disciple here, only shared sacrifice. Stillness creates room to behold another’s pain.

Jacolby Satterwhite, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, “Room for Doubt” (2019)

5-channel HD color video, insulation foam, expanding glue, resin, fairing filler, plywood, faux-leather vinyl, double-faced chiffon, polyester rope, thread, automotive paint, and inkjet print on synthetic cotton. 93 x 96 x 96 inches

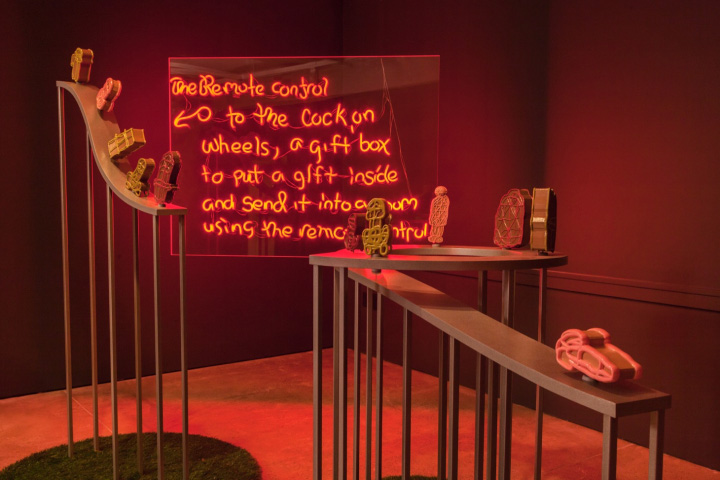

On our tour, Satterwhite said sculpture’s “permanence” makes him uneasy, and it’s taken time to feel worthy of “taking up space.” Music, video, music, and performance allow for infinite drafts, but sculpture feels definitive, a final realization, something Satterwhite’s mother couldn’t do in her lifetime. Patricia Satterwhite, who passed away in 2016, authored a massive body of work, from “155 a cappella music tracks” that inspired “Blessed Avenue,” to drawings and schematics for objects she planned to eventually sell on QVC, the home shopping TV network. Her inventions filled myriad sketchbooks and included such unrealized concoctions as “A water tub seat to soak in” and “a remote control for cocks on wheels.” Satterwhite traced her blueprints and product descriptions by hand, and with the help of his FWM crew, made her 2D dreams three dimensional.

Each piece on the second floor combines sculpture with video except for “The Remote Control for Cocks on Wheels.” Here, Satterwhite has realized his mother’s as-seen-on-TV aspirations within his own nightclub aesthetic. Her squiggly pink, yellow, and green lines are filled with caramel brown epoxy resin and set atop three steel curving pedestals, confections parked on highway off ramps. Satterwhite has used all these institutional resources to make things that stay put. He now has an inventory, meaning he can’t just pick up and leave. Pressing the pause button on the remote control has allowed him to fully reach into his past and render his mother’s legacy. The room feels equally his and hers.

Jacolby Satterwhite, in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, “The Remote Control for Cocks on Wheels” (2019) powder-coated steel, plywood, artificial turf, magnets, PLA filament, epoxy, epoxy resin, enamel, baking soda, superglue, bond filler, plexiglass, LED, and silicone. Sculptures: 62 x 44 (diameter) inches, 78 x 44 (diameter) inches, 54 x 70 (diameter) inches; neon: 48 x 59 inches

At one point in “Blessed Avenue,” a person peaks his head out from a Shanghai alleyway in the deep background to watch Satterwhite dance. A real head dangles, transfixed, enrapt. While much of the beauty in Satterwhite’s videos comes from their intricacy — figures twirling, flitting, and fucking within what feels like infinite scale — it’s nice to watch someone slow down. In another piece, Satterwhite suspends video screens from the ceiling above four black epoxy figurines with cone breasts wearing Patricia Satterwhite-designed shoes. Below a sky of screens, they’re paused mid-dance, mid-ritual, gazing euphorically upwards, maybe at the future. The piece’s title? “Room for Ascension.”

Room for Living continues at the Fabric Workshop and Museum (1214 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) through January 19. The exhibition was curated by Karen Patterson, with studio coordination by Avery Lawrence.