- Source: ART REVIEW

- Author: JONATHAN T.D. NEIL

- Date: SEPTEMBER 2010

- Format: PRINT

Ryan Trecartin: Taking the Real World to another planet

Ryan Trecartin’s manic hyperreality TV soap operas have made him one of America’s most talked about young artists; but are we looking at the real world or another planet?

ABOUT TWO THIRDS OF THE WAY THROUGH Ryan Trecartin’s I-Be Area (2007), Trecartin, Lizzie Fitch (his constant collaborator) and a plump coconspirator named Soda Pop are filming themselves inside what looks to be a hotel room or studio apartment. The jump-cut conversation (though it’s not really a conversation) turns to the subject of the end of the world. Soda Pop says she read about it in the news, to which Trecartin’s character responds, “You saw me in the news. What you saw, it was me.” This gives way to all three characters ecstatically chanting these statements like some new-age mantra, all the while looking into a mirror: “Soda Pop! You saw me in the news! What you saw, it was meeeee!” The session ends with Fitch’s character stating that “it’s all about how nobody loves me”, to which Trecartin responds, looking directly into the camera, “No, it’s not, it’s about how the world ended three weeks

ago, starting now.”

The sensibility here is not unique within Trecartin’s universe, which went bang in 2004, the year the artist graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, in Providence, and reached its current rate of inflation through standout inclusions in the 2006 Whitney Biennial (about which Jerry Saltz of New York Magazine raved) and the New Museum’s 2009 love letter to youth, The Generational: Younger than Jesus (for which Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker swooned). It brings together most if not all of the strategiesthatTrecartinusesinI-BeAreaaswellasthemorerecent K-CoreaINC.K (section a), Sibling Topics (section a) and P.opular S.ky (section ish) (all 2009): multiple characters played by the same people (avatars, copies, ‘command Vs’) in various states of undress and dress-up, often with body and face and teeth painted, sporting wigs and hats and dyed hair; roughly treated interiors (here objects and surfaces are endlessly open to alteration and defacement, if not defenestration); deft, rapid editing (as Trecartin’s most inspired psycho-caregiver of a character, Pasta, says in an earlier scene: “Your life but better! With edits! With edits!”); and a way with language that finds words slipping along their associative axis (“Being postfamily and prehotel ends today for me”), spoken sometimes with the high-rising terminals pioneered in California’s San Fernando Valley back in the 1980s (and heard now wherever a thirteen-year-old is on a cell phone: “Omigohhhhd!”) or, more often, in the lash-tongued style of the imperious, peremptory queen (for whom every line is a snapping finger).

But this particular scene is notable for two further reasons: first, it shows how everything in Trecartin’s world is gathered up into the perpetual present of each character’s ‘voice’ – as when news of the world’s end three weeks prior is condensed into the finality of Trecartin’s “now”; or when Soda Pop’s knowledge of the past is turned into the group’s repetitious chanting in the present. Voice is central. It’s both how the characters hope to register their presence and the marker of how that presence is nothing but a function of the video camera that captures it and the software that mixes and manipulates it. The best demonstration of this comes in Sibling Topics, when Henry, a character played by Holcombe Waller, riffs on some lines delivered by Trecartin’s Auto Ceader, who then stops the manic flow of the scene, as if stepping out of character, to ask for a repeat performance. It’s a momentary exchange, but as Henry treats the viewer to another vocalised riff, with the camera moving in for a closeup, we realise that one’s voice is the only thing that can guarantee screen time.

And second, this scene offers one of the only moments when we catch sight of the video camera itself, and here as it is being wielded by Trecartin. I mention this not to suggest that in this instance we might be witnessing some eruption of modernist reflexivity but rather to point out the one feature of that digital camcorder which would seem both to underwrite and to thematise, in part if not as a whole, Trecartin’s work to date: the flip-out, swivelling or otherwise articulating LCD screen, that nifty little feature that lets you film yourself filming. Not reflexivity, then, but reflectivity. It’s not for nothing that this scene plays itself out in front of a mirror.

Perhaps it is coincidental, but the year LCD screens were first incorporated into video camcorders – 1992 – was also the year that saw the debut of MTV’s The Real World, and thus the emergence of ‘reality’ television in the US (itself made possible by wide access, after 1989, to new nonlinear video editing tools). The coincidence is worth attending to, because MTV’s hit show (24 seasons and counting) introduced its American audience to – indeed the show’s very success hinged upon – what it called the confessional: segments in which cast members would sequester themselves in a makeshift closet where they could offer up, to a tripod-mounted camcorder no less, their most private thoughts on the more public absurdity just outside the door. With its stationary frame and change of resolution signifying that there was no other operator behind the scene, that this person was indeed truly alone and what we were witnessing was this person’s true self, the camcorder and the confessional form opened onto that psychological ‘reality’ which the show’s producers brilliantly realised would be so necessary to sell the so-called reality that was being documented by the show’s ever-present camera crews – call it the American psyche in the age of 24/7 media.

It also seems necessary to acknowledge that the early 1990s were, as the sociologist Thomas Streeter labels it in a 2005 essay of the same name, ‘the moment of wired’ – that is, the moment when a particular conjuncture of information technology and a certain technophile professional class with time on its hands saw the online landscape unfold, or rather unzip, like some secret secondary level in a video game, one that models the original ‘real’ game but promises new and occult knowledge for those whom John Perry Barlow called ‘natives of the future’. That future had an address, which Barlow famously listed as ‘Cyberspace’ (a term itself adapted from sci-fi visionary William Gibson). So the mass consumption of reality television, with its introduction of the confessional form, and the mass migration into cyberspace coincide; and it’s worth conjecturing that the former prepares the ground for the latter’s second incarnation – that is, for Web 2.0: the rise of social media, with its increasing inducement to publicise private life (along with its correlate, the privatisation of the public sphere).

Now, the role that video played within the ‘reality’ of reality television has become manifest in the ubiquity of the online video blog, which is itself nothing other than the apotheosis of the confessional form – and this is the form in which Trecartin has professed greatest interest; it also offers the indigenous context for his work, which one really should watch on Trecartin’s YouTube channel and, more recently, in HD on Vimeo. In the gallery setting, the works’ blistering edits attract attention but rarely hold it; their distraction is more easily indulged when plugged into a laptop while reclining on a couch.

Yet the confessional form also marks the persistence of what was long ago identified as video’s very medium, which is not its technology, but rather narcissism. From the very beginning, video served as a mirror for its artists, one which enclosed their bodies between camera and monitor, and so produced the artist’s ‘self’ as a function of feedback. It was within this closed loop of feedback, now standing as a figure for the logic of the burgeoning mass media, that, as Rosalind Krauss put it in 1976, ‘consciousness of temporality and of separation between subject and object are simultaneously evacuated’.

Lest we think that the combination of LCD screen and camcorder, of monitor and camera, would squeeze the artist out of the infinite regress of that feedback loop and place him back into some concrete relation with the world, we need only remind ourselves of that scene in Trecartin’s I-Be Area, where no objects or subjects exist except within the perpetual present of the camcorder’s frame: “It’s about how the world ended three weeks ago, starting now”.

For all that seems new in Trecartin’s work, his medium, particularly as it is figured within his impressive series of recent videos, remains very much what it was found to be during its first decade of use after 1965. Yes, the technology and channels of distribution have changed radically since that time, but this only goes to show how a medium cannot be reduced to its physical or technical supports alone. All of the critics who want to see in Trecartin some ‘fresh’ or ‘youthful’ or ‘energetic’ new contribution to a stultifying artworld are looking into the mirror of his videos and finding the projections of their own fantasies staring back. What we are witnessing is a feedback loop in which history has no purchase (only purchasing power).

History, then, would suggest itself as the means of accessing what might be interesting and urgent in Trecartin’s work, and this requires working against a very odd and rather specific amnesia. Because, inasmuch as no shortage of critics have mentioned those filmmakers from the 1960s and 70s whose sensibility Trecartin is seen to share, filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger and Jack Smith and the young John Waters (figures of whom Trecartin claims to have been largely ignorant when he began making videos), there has been shockingly little mention of the one word that describes that sensibility – and describes it exactly, I want to say – nor has there been any mention that I have found of the one figure whose first significant critical achievement it was to have articulated that sensibility – and articulated it exactly, I want to add. The word for that sensibility is ‘camp’, and its earliest and most insightful champion was, of course, Susan Sontag.

Why the amnesia? Is it the fact that Sontag died at the dawn of Web 2.0 – of MySpace (became a social networking site by 2004), YouTube (online in 2005) and Facebook (founded in 2004 and open to a public beyond corporate and educational institutions in 2006) – which has kept her out of mind? No Facebook page, no life, online or otherwise? Again it is surely coincidental that A Family Finds Entertainment (2004), widely regarded as Trecartin’s breakout piece, marks both the year of Sontag’s death and the 40th anniversary of the publication, in Partisan Review, of her own breakout piece of criticism, ‘Notes on “Camp”’. Yet sentence after sentence of that piece reads as if it were directly addressed to Trecartin’s enterprise, which is nothing more, and nothing less, than a pure embodiment of a straight-up camp sensibility (not ‘postcamp’; not ‘neo-camp’):

Camp is the triumph of the epicene style. (The convertibility of ‘man’ and ‘woman’, ‘person’ and ‘thing’.) Camp discloses innocence, but also, when it can, corrupts it. In naïve, or pure, Camp, the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails. Of course, not all seriousness that fails can be redeemed as Camp. Only that which has the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve. Camp… cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much’. What Camp taste responds to is ‘instant character’… and, conversely, what it is not stirred by is the sense of the development of character. Camp taste is by its nature possible only in affluent societies, in societies or circles capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence. Camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralizes moral indignation, sponsors playfulness. Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation – not judgment.

This is probably where Trecartin’s particular camp sensibility departs from Sontag’s assessment: his is a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation and of judgement. This is what ‘camp’ has become 45 years on: an air kiss and a bitch-slap at once. The elasticity of ‘family’ in Sibling Topics (section a), or the assault on ‘identity’ in I-Be Area and its multiplication in K-CoreaINC.K (section a), or the rough handling and gleeful destruction of so much stuff (glassware, cars, sets, bodies) in P.opular S.ky (section ish) – it’s all an implicit condemnation, while at the same time it can’t be bothered to take the time to exhibit any kind of ‘care’ at all.

Sontag no doubt sensed this tendency in advance, because it is manifest in what she claimed as that ‘ultimate Camp statement’, a statement that I will adopt as my own in order to say of all that Trecartin & Co have done: ‘it’s good because it’s awful’.

WORKS

(IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE)

Any Ever, 2010 (installation view, the Power Plant, Toronto), with Ready (Re’Search Wait’S), 2009–10, HD video, 26 min 49 sec

I-Be Area, 2007, video, 1 hr 48 min

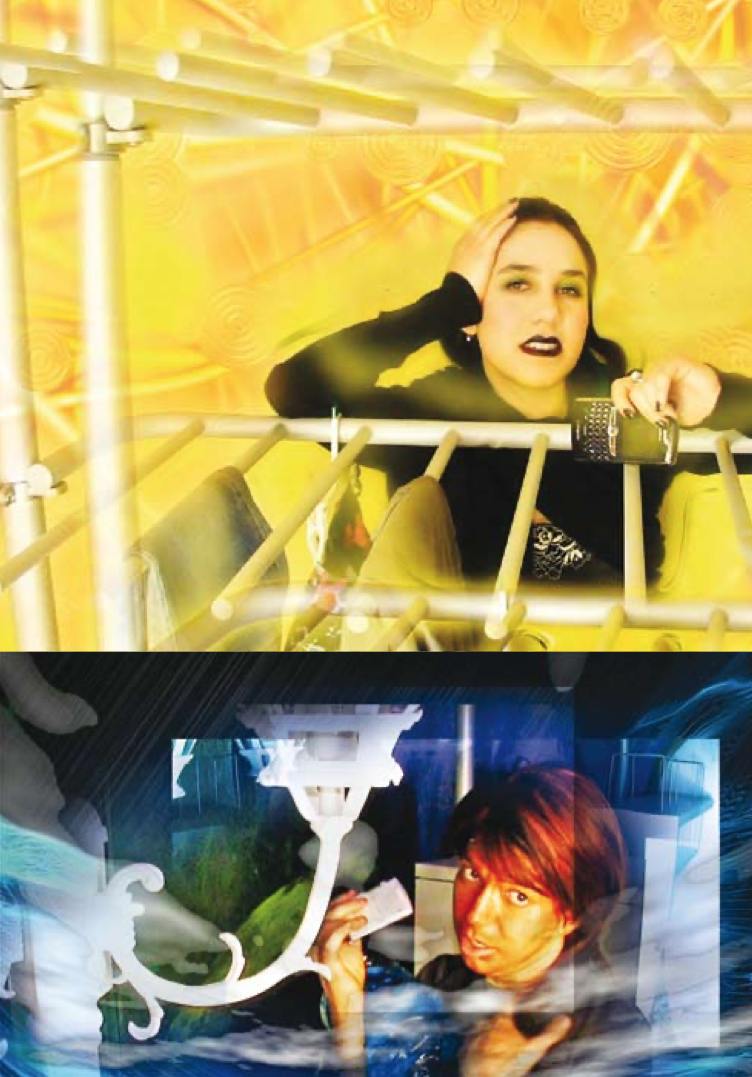

Two stills from P.opular S.ky (section ish), 2009, HD video, 43 min 51 sec

Two stills from Ready (Re’Search Wait’S), 2009–10, HD video, 26 min 49 sec

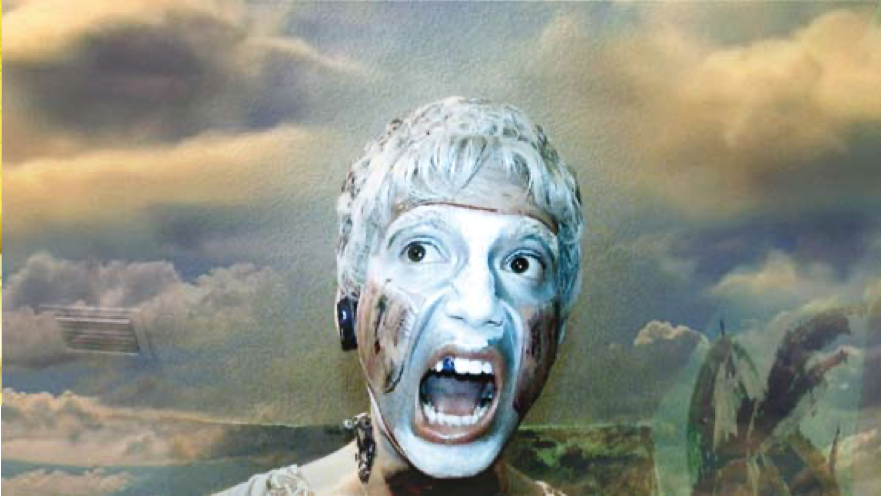

Two stills from Roamie View – History Enhancement (Re’Search Wait’S), 2009–10, HD video, 28 min 23 sec

all works

Courtesy the artist and Elizabeth Dee, New York