- Source: King Kong Magazine

- Author: Isabel Venero

- Date: Issue 15 Spring Summer 2023

- Format: Print

Ryan Trecartin:

In the Present Tense

Ryan Trecartin, A Family Finds Entertainment, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

After 6 years in Ohio and scores of projects of varying size and complexity, the Great Pause of 2020—despite the monumental fear and uncertainty that came with the pandemic—provided Trecartin, and his longtime collaborator Lizzie Fitch, like so many others during that strange and surreal moment, time and mental space to think about the wild ride of the previous two decades. Trecartin was able to consider his work, particularly his current multiphase project Whether Line, with more perspective and clarity, two critically important things as the maker of wildly inventive and conceptually dense artworks.

As much as it’s been a time of reflection, it has also been a time of financial anxiety. With exhibition cancellations and slowdowns of all sorts in the art world, Trecartin immersed himself in the work of longtime collaborators who had been so key to his early videos, principally Telfar Clemens and Babak Radboy. Working inside of Telfar’s world was inspiring and creatively fulfilling and allowed him to step into a different role than the one he normally occupied in his own projects. He also contributed to other projects with friends, like a film project by DIS to which he and Fitch contributed a section, and Circle Time, a collaboration between DIS, Telfar TV, and Terence Nance.

The rural property where Trecartin and Fitch live in southeast Ohio was the setting for Whether Line. Commissioned by Fondazione Prada in Milan, the artists built permanent movie sets which now function as land works. More of these large-scale projects will be added over time, of their own work and those of other artists and collaborators. The eventual goal is to create an art amusement park, and down the line, an artist residency.

The land has been a project unto itself: Trecartin’s planted countless trees, sculpted land terrains and beds for plants, extensively researched plant grafting and mutations, and cultivated a poison garden as well as plants with spiritual or ritualistic properties. Beyond that, he took up drawing again for the first time since high school, and went deep with his passion for bio-hacking which, among other things, has allowed him to augment many aspects of his physiology.

Ultimately, though, these last few years have been about returning to some essential truths about himself that had gotten lost in the mix of Trecartin’s life before the pandemic. He has even taken on a new moniker which was styled by his friends during a trip—appropriately enough—over the new year holiday. Trecartin now sees clearly how he wants to feel and how he wants to work—and in that order.

—Isabel Venero

King Kong Issue 15 Spring Summer 2023, cover and back cover. Courtesy of the artists and King Kong

ISABEL VENERO You just came back from a week in LA—well, we both did. It was an incredible trip. You lived there for so many years and since moving to Ohio in 2017, you’ve only been back a few times. As we were leaving, you said to me it was a really inspiring trip for you.

RYAN TRECARTIN I live in Ohio so I don’t see everyone as much as I would like. Raúl de Nieves is a longtime friend and his band Hairbone played a show while I was there. It was inspiring. I’ve been going to see his bands play ever since we met in person back in 2006, after we met on Friendster in 2004 [laughs]. It was just so special to see a friend who has cared so passionately about performance for so long, and has done this thing that has meant so much to him forever. And he’s still doing it, it’s as powerful and inventive as it’s ever been. It’s still loud and real and raw.

IV That commitment is pretty intense.

RT I know. And people are appreciating it in such wider ways. And so it’s not just specific to a music community, or specific to his peers and the creative people that he builds things with or that he’s inspired by. It’s larger now. I spent a lot of time with Raúl’s gallery there, Morán Morán—they show a lot of artists whom I cherish as people and whose work I love, who are of my generation, a few of which I’ve worked with in different ways. And I just felt like there’s a lot of “arriving” happening with my friends right now. Not that people weren’t arrived, but you have different forms of arriving at different periods of your life…

IV I feel as though you are in some kind of “arriving,” phase too, though in a different sense. You’re feeling an evolution in your life, both personally and professionally at the moment.

RT Lizzie and I, we’ve worked incredibly hard for nearly 2 decades. We really dove entirely head first into production after production—I think we both love being possessed by a project. But we’ve been buoyed as well by a ton of luck. So many opportunities at the perfect moment. When I was snail mailing DVD copies of A Family Finds Entertainment in 2004 to people I met on Friendster, you couldn’t stream video yet. It was a fun way to receive something like that. And borderline creepy maybe. I was cold writing strangers and asking them for their physical address without really explaining why I wanted it. I figured those who answered were likely “my people,” and Raúl was one of them [laughs]. And then two years later you could stream, and I was able to upload that movie and other things I was making to YouTube, which immediately felt like a natural home for what I was doing. And because I had mailed hundreds of DVDs of A Family Finds Entertainment, and there was this energy around this kind of thing, the movie was being played at house parties and music shows. Eventually it reached the eyes of art people during a house party in Cleveland, Ohio, and that just pushed us into the art world. Since then, we’ve gone from project to project nonstop. We never took a break. After the Fondazione Prada show in Milan a few years back which debuted a big new body of work which we are still working on, Lizzie and I just felt burnt out so we crashed a bit. And then the pandemic happened, and that encouraged the crash to just go on longer. And then it turned into this therapeutic period of healing basically, in the most simple terms. Things have transformed so much since 2019 in this way where I feel new.

IV This is something you said to me in LA, which stuck with me. You just kept saying “I feel new, everything feels new.”

RT I feel like I let go of everything—everything I care about and every thing I don’t. And then the things that were still there were the things I knew I truly cared about. I went scorched earth on my sense of purpose basically. And then it was like somehow I was living in the present again. I used to be really good at that. Well, not good at it—it just was something I did.

IV It wasn’t conscious—it just was.

RT Yes. I’m just here and it feels really good even when it doesn’t. In this most recent trip to LA, because I hadn’t been there since 2019, it felt like a return to a home, or at least one of my homes. I thought I was returning to a familiar place, but while I was there, I felt as though this place had actually never really met me and I maybe never met it. I’m a different person now and LA is also a different person now. I lived in LA during some very active years so we basically lived inside a series of productions. Often when I talk about my time there it inadvertently sounds like I didn’t like it. That’s not it at all. Huge life lessons happened when I lived there.

IV That feeling of newness in LA was overwhelming, in a great way.

Ryan Trecartin, CENTER JENNY, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

RT Yes, definitely. I live in a rural area with my friends—Lizzie, Ria Pastor, who is Lizzie’s wife, and Alison K. Powell—they are family. We’ve all been going through a lot of changes at the same time, but somehow I didn’t fully appreciate how much evolving I had been experiencing until I got to LA.

IV I also think suddenly changing your environment, like going on a trip, makes you much more aware of the changes you’re experiencing. The context shift puts everything that is new into relief.

RT Exactly, the volume went way up. I think that’s fundamentally why Lizzie and I have chosen to move so frequently in our lives, because it’s a way to artificially…

IV …catalyze or instigate this kind of process.

RT Yeah, my family moved a lot when I was growing up, and I always loved it, because changes that are happening in your life suddenly become official when you’re in a new place. New places ask you to adapt. They encourage transformation and challenge expectations. So much can be activated in the learning curve of a new place.

IV That love of moving is your Aquarianness for sure, which I don’t really get, even though I have a lot of air in my chart too. Change in general is very destabilizing for me—getting used to new things and all that. I was just looking at an interview with you from 7 years ago, and you say that exact thing, “I love moving,” and the interviewer’s like, “What? Nobody likes moving.”

RT It feels so comforting to move, it’s like taking a life shower. It’s not like you are moving away from people.

IV Well, sometimes you do.

RT [laughs] Yeah but you can do that without changing your address. A physical move doesn’t necessarily mean you’re moving away from someone emotionally, which is some times what I think people fear most about moving.

IV What was clear to me when we hung out in LA is that you’re really excited about what is coming next for your work.

RT I’m excited about making work for people to experience. Over the last few years, I was making stuff for myself, because I’m always making something, but that’s different.

IV What have you been working on?

RT I’ve been making a lot of music. I did a series of drawings…

IV There was a burst of energy around making those drawings. Every night for many weeks…

RT I used to draw in high school, but I just stopped because I suddenly had the outlet of a video camera and a computer to edit on. These tools felt more language based to me, which is where I felt most drawn to. Drawing was a medium that worked at the time. But that impulse came back suddenly in this way that I associate with a time before I discovered editing software.

I think people have this misconception that I’m not a hands-on person, just because when Lizzie and I talk about our collaborative practice, it’s always in the sculptural realm and sets and costumes. And because I do the writing, shooting, and editing of the movies I’m more often thought of as a director type and Lizzie as a builder type but in reality we are both. We both like tinkering, we like making things and organizing things. We like breaking things, and then putting them together in different ways. And Lizzie loves directing. My drive to create and build on a smaller scale has always had a home inside of a larger project for years now. But in some ways I had forgotten what it felt like to be making stuff simply because it’s just how I process life and learn and live. I hadn’t made things like that in a very long time.

IV Yes, that all makes sense. It’s true that I think of you less like a tinkerer. My sense is that if Lizzie sits down for any period of time, something will come out of it. She’s going to knit something, she’s going to make a mask, a hat, or build something. I still have these incredible bags that she made for Christmas years ago—they were made from survival gear fabrics.

RT Totally, the difference in how we approach that kind of thing is what conjoins us in a special way. The part of me that makes things because I have to just function differently when I’m developing a project because a part of my brain is always pushing the things I make to fulfill a project-related purpose as material or supplies for the whole. Whereas Lizzie values having creative projects that are ongoing that she can approach in a hobby-like way and these run alongside her art practice. She thinks with her hands, loves building things, and has a deep passion for material puzzle solving—it’s so inspiring to be around. In this way she is always creating something artful outside the scope of our larger projects, although usually these creations eventually find a home inside a project [laughs]—as inspirations, techniques, sculpture materials, or movie props. Like a lot of artists, we put everything, all our resources and all parts of ourselves, into whatever project we’re working on. It was just interesting to find myself making things on a scale that can happen in a single day or a week without the intention of sharing it beyond my circle of friends. Most of this making or building energy I’m describing happened with plants and trees. I was working on a poison garden and I’ve read a lot about tree grafting. I experimented with combining trees, planting them really close together so they would eventually intertwine. I made different plant beds that were like sculptures, though I wasn’t thinking of them that way. I think about the future when we’re old and we’re visiting this site—I just want there to be aged trees that are doing weird stuff. The artist Precious Okoyomon and I have been discussing plans to develop a forest as a living sculpture. It will basically be a community of multi-graft hybrid trees and shrubs using aeroponic and tree-shaping methods with weather activated sound design. This is kind of a long-view life project. Lizzie and I hope to develop a bunch of features on the site here in Athens with artists and friends which would have long time horizons. But back to the trees: you have to start now because I mean, I’ll be old pretty soon.

IV You will. Sad, so sad. [laughs]

RT It will take that tree 30 years to begin to present as a mature tree [laughs] and that’s when I’m 70.

IV This period of exploration was something that was always part of what you do in your work, but it sounds like this recent moment has had more freedom.

RT Yeah. [laughs] I am always working towards a goal and an endpoint in whatever I do. But there are differences when it emerges out of something you’re inspired by versus something you are obligated by and you care about the obligation because you want that obligation…

IV … or opportunity.

RT Well, yes. When you accept an opportunity then it gains some obligatory traits [laughs].

IV Or a commitment.

RT Yes, “obligation” was a funny word to use. [laughs] With the trees, I’m thinking about 30 years from now and what it will become. It’s a proj ect like any other, whether it’s fully realized in 3 months or 3 decades. But I imagine a tree project as something that’s never realized, but is rather ever realizing, and I think that will be good for my brain.

IV It’s not about open-ended research. You are always looking at what something will become.

RT Yes, for example, with the music I’ve been writing, I’m now thinking of an eventual audience for it and writing more because of that. My friend and musician Aaron David Ross and I have been talking about releasing some albums. I was doing sound design for Telfar, and I began to think that the songs I was writing sounded like carpets. Once I realized it was carpet music, I began writing hallway music and garden music as well. Working with Telfar the past couple of years and working on the DIS film “Everything but the World” was so fun. In my own work, I try to create a platform for collaborators where they can have a different sense of responsibility and creative outlet than when they’re making their own work. And working with Telfar afforded a similar experience for me. I’ve worked inside of his work a lot in the past, but this was on a different level because the scale of what he’s doing with his clothing brand has expanded so much. In this process of working inside of others’ projects, I’ve grown a lot as an editor and sound designer and collaborator. It’s been so rewarding.

With DIS: they gave me a concept, and asked me to write a script, shoot and edit it, and then they would place it in the movie. I love working like this in my own work but I was able to experience the other side of that process with this project and it was a blast. Telfar and the DIS collective—Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, and David Toro—are family and it’s such an incredible way to work. I also worked with the artist Jesse Hoffman on a video piece he made. I got to act in his script which was fun and then helped with the edit some.

Ryan Trecartin, Panda Louie as Korra & Asami, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

IV I’m really interested in the rituals or preparation artists go through to make their work. My experience of some painters that I’m friends with or I’ve worked with is that they go to their studio, get on their computer looking for things to paint or they scour books for inspiration or creative prompts. That kind of research jogs something in their mind. What’s involved as you get prepared to take on a new project?

RT I think writing music and dancing, those are two things I always do before I start working, for months. And just while writing music, I start to hear a dialogue in my head. And then I start to write and then it slowly becomes a script.

IV Being around your friends also prompts a lot of your ideas as well…

RT Oh definitely, that’s the top of the list. [laughs] Friends, conversations with friends are everything. I like what happens when our energies combine when we are together. The call and response of hanging out, or the way humor emerges from a group in real-time tethered to an active experience. The ways in which people navigate the social aspects of public settings inspire me in an extreme way.

IV You went to New Orleans recently, where you used to live at some point in the mid-2000s. You had some kind of epiphany around your name while you were there.

RT [laughs] I went to New Orleans for New Year’s with a group of friends and while we were there, we started talking about names and our associations with different names—I said some drunk shit about how I needed a new name because I was feeling like I’m about to start a new phase with everything in my life. But as I said it half-jokingly, I realized I was serious: I wanted a new name and I wanted my friends to pick it. A name that would refer to the person my friends know. I’ve always felt plural, so having more than one name felt in line with that. For a while, I had been feeling like “Ryan” belonged to what I do, what I’ve made, and how all of that is seen or understood by the world rather than to who I am. At some point, Telfar said, “I’m gonna call you by your middle name, Burdell—you seem more like a Burdell than a Ryan anyway.” But that’s my dad’s name. We ended up in some name game chaos and once it morphed into Rydell, it just made sense—like it belonged to the act of living life whereas Ryan now seems to belong more to the things I make after they are made. I don’t hate my given name at all, it just stopped feeling like it was mine. That said, I’ll totally answer to it, and I’ll continue to author works under it. Being in NOLA somehow unearthed my sense of wanting something new to embody.

All my biggest idea moments or moments when I suddenly feel inspired or transformed, almost always come from hanging out. It’s often something about a context and the different behavior sets and sense of timing that are ignited that really gets me going. I love taking in mannerisms and behaviors—not really in a people-watching sense, I’m too participatory for that [laughs]. I just have a passion for movement—body language and eye language and hair language and facial expression … basically all forms of communication.

Beyond imbedding deeply in those friend moments, another thing I do to get ready for working is I obsess over bio-hacking and I read tons of different scientific research papers and I collect that information in a very basic way that looks like research. I try things that have only been studied in rats [laughs] and it’s not necessarily smart, but I have so much fun doing it.

IV That’s not some sort of preparatory tool for work is it? I just thought you were always engrossed in some bio-hacking activity or another.

RT Yeah. When I’m working really hard, I often give up on it just because I’m focused on the work. I might have a couple things I’ll carry through but the actual true experimenting is not really smart to do while you’re working, because who has time to recover from an experimental peptide or research compound gone wrong when there’s a deadline [laughs]. When I finally make the leap from years of research to grey-market purchasing of a research compound, I hold the thing in my hand for a while and if I get any sense that my body or the space around me is saying “No, don’t cycle this,” I immediately put it in storage. The things I’ve tried have worked out great mostly so far…. I mean, fingers crossed.

IV Speaking of being deep into a project: You’re about to start editing Whether Line again, which was that expansive body of work shown at Fondazione Prada a few years back. There’s an edit of the video shown there but that was solely for the installation and not a movie in its own right.

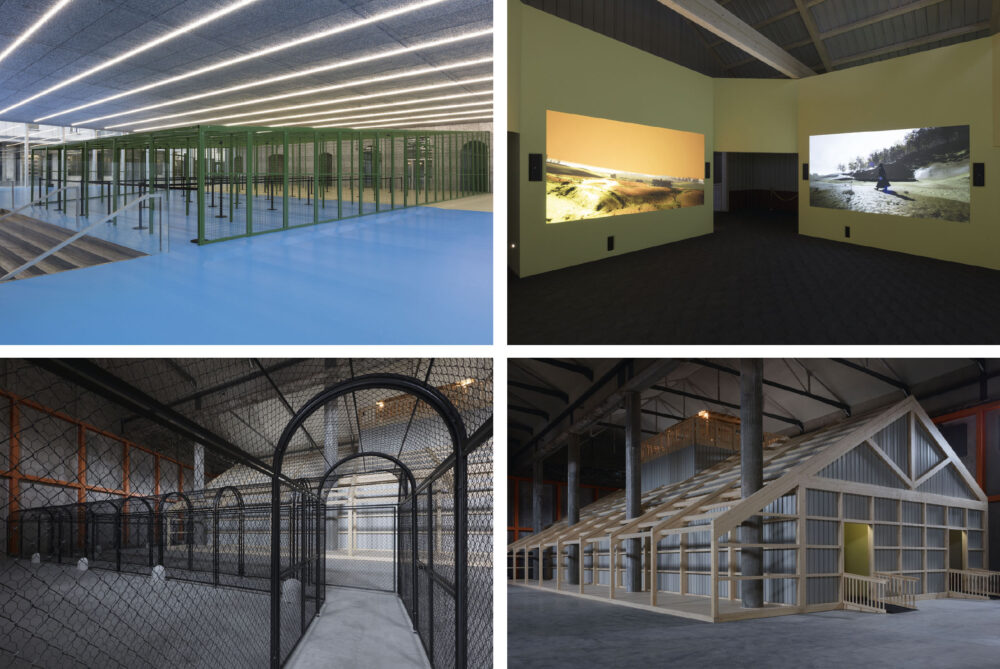

RT Yeah, it was a series of sculptural settings that functioned as one large work. The experience of navigating the path of the show was the work really. Different parts had titles, but the entire experience we considered to be a single work. Plot Front was the room that featured the most movie-like video, but it was not a stand-alone movie. In Property Bath, an adjacent room, we developed something with the artist Rhett LaRue who had been working with Unreal Engine, which is software for game development and 3D/VR world building. Rhett and Ria put the land surrounding our house into a 3D space using drone mapping and documents from the county. We designed the house I now live in and the other permanent sets with Rhett—they existed as 3D models in Maya before they were built. Rhett rebuilt the land and all the sets both in Maya and Unreal so that we could work with the entirety of the landscape and sets as an animated space that was fully navigable like a game. We hope to eventually develop Neighbor Girl, the main character in Whether Line, as a game.

The entire installation opens with Neighbor Dub—a path-like space with a sound piece that moved you into the building that housed the video work. This part of the piece was meant to conjure several different kinds of paths: trails in the woods or a park, or the winding queues waiting for a roller coaster at an amusement park, or the security checkpoints at airports, or the corrals used to trick cows into walking into a slaughterhouse.

After this show closed, my plan was always to further develop the main video piece into a movie. But I needed a break. And then the pandemic made the break longer, and then I made it longer. And so this will be the first time ever that—besides the footage I shot in 1999 while in high school which became the movie Junior War in 2013—I’ve taken years away from footage before working it into a final movie form. I worried such a long pause would fuck me up a bit, but it’s the opposite—I’m so excited. With this long break, I will have a kind of perspective on the footage that only time can provide and that feels generative.

We had a total of 59 shoots, and the video Plot Front uses only a portion of 15 shoots, so there is lots of material to craft more movies from. And I’ll probably end up wanting to shoot more just because during the construction of our permanent sets, extreme rain and so many other things caused the builds to collapse essentially. It was a huge logistical challenge. The builds and the movie were on different timelines as a result. Timelines that my scripts hated at first. [laughs] And so we started shooting while things were still in progress, which ended up being really cool for the project. In hindsight I’m so thankful this happened, but it wasn’t a part of the initial movie scripts or plan. All of this affected my sense of what was actually done or not—I kept on behaving like a script wasn’t done when it was. So I would shoot it 20 times while asking myself, “Why am I still shooting this script?” The fits and starts of the builds were mirrored in the way I wrote additional scenes, developed characters, and the way I structured and shot the scenes. With things like this, once I notice something emerging on an intuitive level that contradicts our initial plans, or seems to be working against what I thought the goal was, I’ll double down on it, and try to figure out where it’s coming from by letting it happen, even purposefully mimicking it. Eventually I’ll rework my scripts to harness meaning out of it, and purposely mobilize it as a concept that is generative and specific to the project’s conditions. For me a mutated plan that wanders off-path is where I end up uncovering the deeper, more challenging questions I want to be exploring.

IV So what was happening with the site was infecting the movie process and the content?

RT Deeply. I imagine as I dive back in I might find holes in the material because I’m looking at it all through a different lens—my sense of what can be created out of the footage has expanded a lot. The scripts and shoots were pre-pandemic but they weirdly feel somewhat of that time. Or maybe the material just feels more complex post-pandemic.

IV How did you feel about language inside of Whether Line? The movies are known for their language. Some of the movies are more conventionally narrative, and it seems, at least in the video that you’ve already shown, that it will be more like that.

RT I think the script for Whether Line has this weird quality where, in some ways it’s more narrative, which may feel more akin to earlier movies like I-Be Area. But in other ways it doesn’t unfold like a story and characters recite dialogue that is merely descriptive, observational. Narrative plot points are framed as locations on a map, as fixed places that can be visited, rather than being delivered through the actions of characters. So much of the dialogue has narrative implications that suggest a sequential sense of time but, instead of moving along with the events that are unfolding as story, the idea of an event eclipses the activity of it. By that I mean, the dialogue is delivered as though it is a reminiscence not of a previous event but of the present moment—there’s a strange temporal disjointedness that happens because of this. And, again, these moments are talked about as if they were locations. Even when a character is among other people, they talk as though they are alone commenting to themselves or to a friend who wasn’t there. I don’t know when this quality became clear to me but I noticed it emerge in the writing process and then I doubled down on it. I think this approach evolved out of a few things: The ways in which the movie shoots were out of step with the building of the sets, and this concept that I wanted the movie to somehow feel map-like in form. Most of the dialogue is written as a two person dynamic in ways that feel particularly tied to a “on the front porch sitting in a rocking chair” ethos [laughs], where characters say to one another, “I wouldn’t say this to just anyone so don’t repeat what I’m about to say.” And at the same time, all the exchanges feel like they have happened before and will happen again—repetition is a device that I use a lot, in this movie and in others. Here, it’s like the plan versus what’s actually happening versus what you think about both the plan and what’s actually happening—all these states coexist simultaneously.

IV I know the writing process was harder with Whether Line, though I think not just because of what you said earlier regarding the movie shoots and the building of the site being out of sync. I think there were other impediments.

RT I think I questioned whether I wanted to make something different, meaning not make a movie, and find another way to realize the ideas in the project. I think this showed up in the Milan show with how I decided to make an edit that was only meant to function in the setting of that room where it showed. And while I was writing, this idea kept coming up in the scripts. There are characters that actually say, “I don’t want to make a movie anyway.” I also merged my movie-making angst with some shifts I was noticing in the ways people were telling stories in real life. I got really obsessed with the idea of stories, the ways in which they can be used, and this idea that people don’t actually want stories anymore.

IV That’s right—I forgot there was a strong anti-story sentiment from the characters.

RT Yes anti-story. [laughs] But I was also coming at that from two different angles. I was thinking about the larger conversations everyone was having at the time about one’s truth. And that veered into discussions about who can narrate what stories. At some point I was like, Wait, what’s the story? Do I know what a story even is? A story is fundamentally different than a list of facts or events, of course. It’s a perspective, not an inventory. In the larger culture there seemed to be a complex negotiation about what a story is and how it should live in the world. I extended this idea to imagine a world in which people had decided that we don’t need stories anymore. I thought, What if people start to prefer data in the form of personal truths and facts, over the messiness of storytelling.

IV I think it’s about, like you said, who gets to tell anyone’s story. It’s about permission around your relationship to everything around you.

RT Yes, it’s a super important conversation. I process the world by imagining everything as a movie scenario, basically [laughs], for the sake of exploring the guts of an idea in my head. And it’s usually some kind of a very twisted perverse social sci-fi thriller horror drama mess with lots of physical comedy and reckless behavior. Whenever I notice cultural shifts emerging that represent changes in the perception of collective value systems, understandings, and meanings of things, I find that I want to explore by fixating on it and having an overly simplified, extreme reaction to it. Like, “Well, we hate this now. And everyone agrees that it is fucking fun to hate it.” I always found that to be a compelling way to start to break anything down. It’s really hard for me to hate something, so that attempt ignites novel ways of thinking or looking at the thing so that I can have a different relationship to it hopefully. If I actually hate something I might even try to write it as a love story in my head. One of these attempts at understanding something for Whether Line was “We hate stories now.”

Lizzie Fitch / Ryan Trecartin, Whether Line, 2019. Courtesy of the artists.

IV Beyond this idea of hating stories, what else is Whether Line about?

RT The concept of property—in all the meanings of that word—is a critical idea. I’ve often talked about characters as being vehicles that have properties, as in qualities or characteristics, that are transferable. For example in Any Ever I suggest personality traits are something you can access, design, and share, or even subscribe to, rather than something you inherently are. Within Any Ever, these ideas were dependent on a reality in which models of ownership were replaced with usership. I thought about the liberatory potential of this particularly as it relates to identity, but there is a more sinister side of this idea, in thinking of the way property, meaning something you own, actually functions. The notion of physical property— land as one of the obvious examples—is inextricably linked to the history of colonialism, occupation, and capitalism.

I described some important ideas in this body of work in the interview on our sound practice in this issue but I want to reiterate them here: Whether Line complicates concepts of personhood, property, history, story, access, and class by placing them in tension with a type of tourist-based mobility that is enforcing concepts of preservation beyond land, nature, objects, and architecture. It’s sort of a horror movie disguised as a security screening. In this movie, we are imagining a type of settler class that colonizes context and history in the guise of an amusement park. People are turned into features where their conditions and abilities become prescribed properties of the park—the approximation of a person’s local-hood, implied experiences, sense of purpose, and endangered identity status are registered and then reduced to a set of rules determined by the town’s memory which is “written” by the tourist class, or access class as it’s referred to in the movie. The town’s memory and “code” no longer belong to the local community. I think of this as the stanchion rope effect. These ideas of a place and time under protection are described as inherited culture preserves on a larger concept map known as the Anthro-Apology Tour.

IV In thinking about how you construct Neighbor Girl’s identity—which is defined as a function of her position, her physical location as the place where borders meet—you provide a somewhat different understanding of identity formation as developed in I-Be Area.

RT With I-Be Area, I was trying to describe what I thought personhood was, basically, and that it did not reside in the body, it was not of the body. Rather it was about the negotiation of experience. And it’s of all the shared spaces, whether you want those spaces to be shared or not. And you don’t get to fully decide who you are because you’re interacting inside of a world, you’re of the world. So the world you inherit, and the conditions you inherit, create feedback, and you’re participating in something that is a whole, and so as a being, you’re an area, you’re not just a body. And I try to write from a place that assumes that as the definition. So the stories have these weird qualities because of that.

But like you said, with Whether Line, I was thinking about physical space. I was interested in people living in homes that are considered historical and how, when they want to alter them in some way, they’re not allowed to do so freely—I think this is hilarious. How do we define what has historical status and what doesn’t? I find the whole concept of preservation funny for some reason. It’s super extreme what it says about what we prioritize and what histories we value and those we don’t. Digging deeper into this idea of historical preservation I began to think of the conversations around identity politics and this led me to this horror movie idea of defining a person as a historical site.

IV In how you are describing Whether Line there seems to be some parallels to CENTER JENNY. In that movie, characters navigate a system with lots of rules, much like a game, and they move through this hierarchical system through assimilation. Is that accurate?

RT Sort of. There’s a side plot that a rich kid is using this gaming environment to outsource their human era history homework—her name is Sarah Source. There are different Jenny Levels in the system and the goal is to be as close to the source material as possible without becoming it, because you still want to be noticed. You don’t want to be so far left of center that you’re no longer considered a Jenny. In the system, when you become overtly left of center you gain host status, you represent the margins of the game’s playability and so you are literally embodying the limitations of the system. Some characters seem to activate host status for a different type of mobility that is creatively more freeing, but it’s a mobility that is more laborious and oppressive because the system is Jenny centric. Since it’s a gaming system you get the sense that this status, the left of-center syndrome, is maybe accessed for recreational reasons that are actually pleasurable for the players—maybe there’s a community of players that have built up around using the Jenny system game in off-brand ways to see who can best “self-marginalize” under the terms.

Back to the Jennys: If you are trying to be a Jenny, and you get too close to the Jenny source, you become the source and you’re not…

IV You don’t have mobility anymore.

RT You don’t have mobility. So it’s this game of being … I keep thinking of the word “dissonant” in music, where you’re supposed to play this note for it to sound like harmony, but you play another note instead. You want to be the dissonant note.

IV To an extent though, right? Ultimately you still need to be able to navigate the system which is dependent to some extent on your sameness to others in the system, your assimilation.

RT Yeah, still somehow harmonious if your goal is to be a mobile Jenny—if the note is overtly dissonant, then you host. And while conformity is key, the goal of the game is micro-difference—to become as similar to the source material as possible without disappearing into it. Since this is a multi-player game, the conundrum of “unique conformity” is the puzzle being solved. If you are playing by the system’s rules you are attempting to be noticed as a member of the Jenny chatter, not a host.

It’s like when people talk about themselves as being different, they’re often conforming in a way that’s just a little adjacent to the norm, so that people can even understand that it’s different. The Jennys are trying to be the same but also minorly different—and this very minute difference is overly valued.

IV In so many of your works, in particular CENTER JENNY, permissions, limits, and rules are critically important to the content. And the concept of borders is also related to these ideas, and they come up a lot in Whether Line, as you described. These worlds you build in your movies are heavily influenced by your interest in games, about a set of rules and applying them and navigating them. And to me that’s a really interesting through-line of the work.

RT You saying that is making me realize that all the movies are about rules. [laughs]

IV Do you think this idea of navigating systems, about the preoccupation with assimilation or dissonance or difference is related to code-switching? How we all have to manage living in certain contexts?

RT Well, yeah. I think code-switching’s a beautiful thing, or it can be at least. You and I have had conversations about me being closeted as a teenager before I came out when I was 19, and I think certain defense mechanisms that are developed by a person or a community often become talents—like protective adaptability and skills are often deployed in social settings as play. It can become a place where humor is created and joy is found, and it’s where pleasures and languages are made that are specific to how your community negotiates the experiences and conditions of navigating the larger world—I think a person doesn’t necessarily drop these things because they’ve healed or found their people or fixed something. Because we are adaptable and find ways to have fun, and so the fun part of it will likely shift but still be fun. So I feel like there’s a lot of creativity in code and the urge to compartmentalize code and shift and use it as supplies definitely shows up fast for a queer kid growing up at a time and place in the country where you were afraid. But when you’re in your adult life, maybe you’re not using it necessarily because you’re afraid. You’re using it because it’s something that became naturalized to you, and it’s maybe become a place of joy and a route to humor.

IV You see code-switching not as a denial of who you are but as a talent, I think.

RT Yes that is how I have thought about it. But maybe when it’s that, it’s no longer considered code-switching, I don’t know.

In I-Be Area, there’s a lot of homophobia. It’s said from a perspective of being gay and queer. That aspect of the movie is maybe less funny today, but at the time, it was really funny to me. Perhaps originally it was coming from a place of pain, but at that moment in my life, it wasn’t. You know what I mean?

IV Sure, I’ll take your word for it. But who knows?

RT Well, I know I hope. [laughs] And what I’m saying is that it was birthed out of pain, but the exercise of it at that time was a form of play and fun.

IV Because you exorcized it? As in exorcism?

RT Well both exorcize and exercise, and even a form of therapy. Exercise like practice, and exorcism, where playing with code-switching— adopting a position that is more the norm, even if it means you’re attacking yourself—is a type of processing and release.

The lazy river / trench in progress, Athens, Ohio, 2018. Courtesy of Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin

IV You were discussing earlier how the build-outs of the various large-scale sets and land features for Whether Line and the problems you were experiencing with them because of the weather, etc, were “infecting” the ideas in the project. This project has been the most ambitious you’ve ever undertaken for lots of reasons but in large part because of the land features, which are, in essence, artworks that also functioned as sets for the movie. These land works will have their own life as well outside of this project though. In 2017, you and Lizzie bought this property in Ohio because you envisioned a project of this scale. You’ve described the site over the last few years as a conceptual amusement park. I remember talking to you 10 years ago about wanting to do something like this and in particular the idea of a large scale pool or water feature. You’ve finally been able to realize that vision.

RT The three “amusement park” features/permanent sets include a public pool–size lazy river / trench we embedded in the hillside, a 50-foot watch tower in the woods on the top of a tall hill, and the composited hobby barn house where I live, which was created from materials ordered from a farm supply store. These were the builds that were so rowdy—the land kept eating equipment and mud sliding because of the severe rain. It was impossible to predict one day to the next what would happen. So the process was long, comical, and difficult. But it all served the larger project in inspiring ways, and obviously most importantly, we have built something that will be a lifelong project. I mentioned earlier that Precious and I are working on a project relating to the trees. Other friends and collaborators will eventually build experiential park features on the site—a sculpture or a structure or a ride, either temporary or permanent.

IV Before we end, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the most important femme in your life, your cat Panda Louie. You have some ideas about her being a reincarnation of you from an earlier life.

RT I live in a house with Alison, which is next door to Lizzie and Ria. They always have tons of animals so I get to have all these interactions with cats without the responsibility [laughs]. I still don’t know what I think about the concept of “pets,” or I guess, the notion that an animal is yours is weird, but I guess many people don’t view pets that way. I do know that I think interspecies relationships are so important and deeply life changing and special. I always thought that I would want an animal to find me and choose to live with me somehow because I would want to know the animal wasn’t forced into companionship simply because beings adapt. So I put it into the universe that I was ready to have a roommate who isn’t human, and I was hoping one would find me. Then a few weeks later this black cat starts mirroring my movements outside, walking around very far away from me but watching me the whole time. Each day she came closer and then suddenly it was clear she wanted to be inside, so I let her in and now she comes and goes whenever she wants. I knew her name instantly, as if it used to be my name or like she told it to me telepathically—Panda Louie. I had the weirdest sensation, like I jumped into her body and she jumped into mine, and that we were both each other’s past lives. She remembers living my life and I remember living her life. I started obsessing over the yard and making cool things for her to experience—I thought, Well, when I experience this as Panda in my next life, I want it to be fun, or when both of our lives are merged again in the other realm and we experience both perspectives as a whole, I want to know that I made decisions with our shared future past in mind. She goes on long hikes with me in the woods. She’s developed a lot of ways of communicating with me and she has trained me to do tricks for her. This cat has domesticated me.

IV I’ve known Panda Louie since she adopted you and you have lots of stories about her but somehow I have never asked you this: Have you ever felt this way about a human being? [laughs]

RT Not yet. I’ll keep you posted.

Installation views, Lizzie Fitch / Ryan Trecartin, Whether Line, Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2019. Courtesy of the artists and Fondazione Prada, Milan

Isabel Venero makes books with, for, and about artists. She lives in New York City.