- Source: The Los Angeles Times

- Author: CHRISTOPHER KNIGHT

- Date: MAY 17, 2021

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Review: Cauleen Smith’s marvelous Watts Tower wallpaper

at LACMA gives toile a tweak

Every now and then over the past half-century, wallpaper has stepped forward to play an unexpected leading role in art.

Yes, wallpaper.

In the 1960s there was Andy Warhol’s frilly pink cows, which queered Picasso’s self-identification as art’s macho bull. In the ‘70s, Tina Girouard went around the bend of Conceptual art, replacing rigorously mathematical wall drawings with geometric bits of grandma’s parlor décor. Later, Jim Isermann affixed abstract vinyl decals to museum walls, transforming a high art institution into a domestic home for acute DIY craft.

Now, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, wallpaper is a linchpin in a marvelously multidimensional installation by Cauleen Smith.

An L.A.-based filmmaker (she’s on the faculty at CalArts), Smith unsurprisingly brings a cinematic quality to her absorbing wall covering, one that careens through layered time and space. Her design plays on toile de Jouy, the popular 18th century style of French wallpaper and textiles that shows imaginative pastoral scenes.

Toile, produced at a factory just outside the sprawling palace at Versailles, became a staple of escapist aristocratic interiors, flush with romanticized views of happy milkmaids and contented cowherds or fantastic visions of far-off Chinese pagodas. Smith, however, assembles views more personal and closer to home.

Nestled among her organic linear designs of fields and trees are renderings of Noah Purifoy’s rambling desert sculpture garden in Joshua Tree, the peaceful ashram in Agoura built by Alice Coltrane (and consumed by flames in the awful tragedy of 2018 fires), the famous open-framework spires of Sabato Rodia’s Watts Towers and other sites of spiritual and creative life, many associated with Black culture.

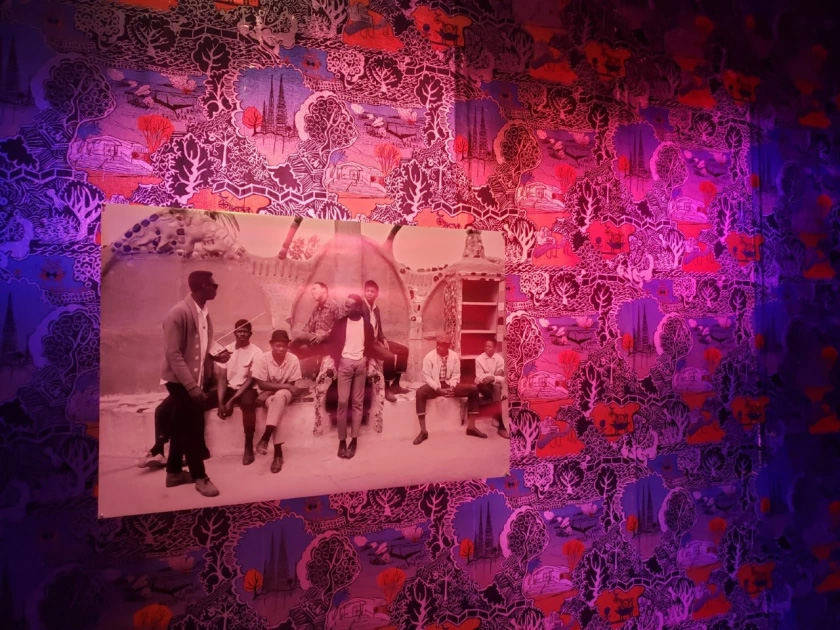

Printed on vinyl, which diffuses reflected light, the wallpaper is installed opposite a projected film of a small, white clapboard building in a grassy field — perhaps a rural church or meeting house. A single framed picture hanging on the wallpaper shows nine dapper young Black men relaxing at Watts Towers.

They were photographed by Bill Ray for a 1966 Life magazine essay on the prior year’s Watts Rebellion, but the picture was not used. The serene photograph didn’t fit the publication’s narrative, promoted on the cover as a gripping story of “arson and street war — most destructive riot in U.S. history.”

The magazine plugs “11 pages in color” inside — yet, notably, Smith’s displayed reproduction is black and white. The difference makes a stark editorial point about exclusionary stereotyping in mass media.

It also deftly conjures a once common, now-discredited history of photography as art. As declared by documentary photographer Robert Frank, whose influential picture book “The Americans” was published in 1959, “Black and white are the colors of photography.” Until relatively recently, color camera work was for commerce while black and white was for serious art. Smith, reversing Bill Ray and Life, grabs the obsolete debate and turns it upside-down and inside-out.

The light in the gallery is low to accommodate the nearby projected film, with floor-to-ceiling glass in an adjacent window wall covered in gels in primary colors. Natural light streams in, filtered through the electronic colors of TV. Like video artist Diana Thater, who has often used the device, Smith bathes the experience of her installation in the visual tints of media mingled with those of nature.

Overhead, blue spotlights illuminate the wallpapered wall. Moving in close to peruse the design and Ray’s photograph, your body comes between the spotlights and the wallpaper. Unexpected things happen. A soft halo of splintered light forms around your shadow, framing the layered scenes of spirituality and creative life. Walk along the length of the gallery’s very wide wall and the sanctifying aura moves with you.

With the memory of the Watts rebellion fresh in mind, though, the spotlight shining down from above suddenly edges into an unsettling suggestion of surveillance. You’re being followed. With the filmmaker’s time-based cinematic skills operating in fine form, you shift from an enlightened being into an object of suspicion.

This double-edged attribute embodies the power of “Give It or Leave It,” as Smith’s expansive installation is titled. (The show, which has been traveling for more than two years, was organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania.) A bit farther on, a trio of stacked video monitors shows something simple: women assembling lush arrangements of cut flowers in vases — an everyday activity that, in this context, conjoins life and death, creation and mortality.

There are more parts to “Give It or Leave It,” unfolding like scenes in a movie. A filmed ritual at Purifoy’s sculpture garden. A sculptural mound of mirrored disco-balls beneath a banner trumpeting a famous quotation attributed to a fictional bartender that journalism’s job is to “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.”

Most elaborate, a big round tabletop displays homey artifacts (dolls, books, potted plants, knickknacks) on which live video cameras are trained. The images, mingling with filmed scenes, are projected in overlapping layers on surrounding walls in ways that completely reconfigure and distort what you see on the table with your own eyes.

The room’s big, shifting, projected pictures are like Robert Rauschenberg silkscreen prints and paintings blown up to epic scale and set into constant motion. That an insistent, destabilizing environment is more captivating and compelling than the simple pleasures laid out on the table prompts a realization about our current existence that lands somewhere between perplexing and alarming.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., (323) 857-6000, through Oct. 31. Closed Weds. www.lacma.org