- Source: Out Magazine

- Author: ANDREW DURBIN

- Date: March 11, 2015

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Privilege and Its Discontents:

The art of Jacolby Satterwhite

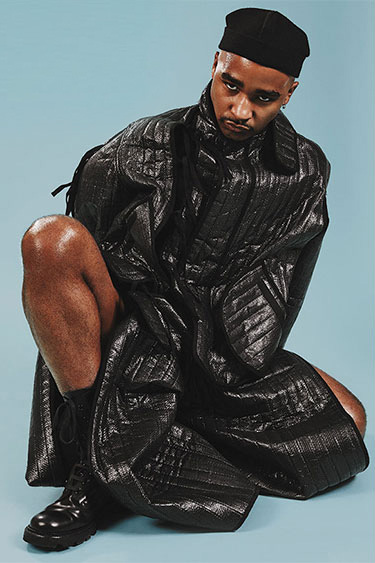

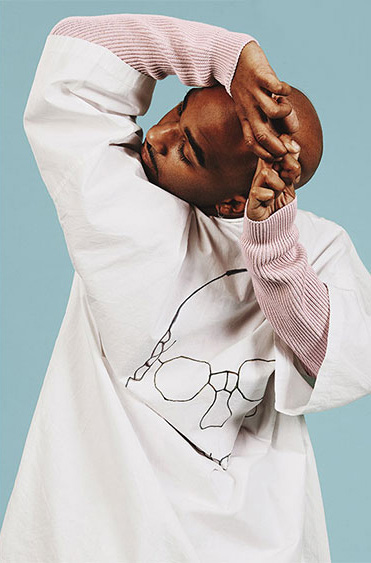

Photograph by Aingeru Zorita. Styling by David Casavant

By his own calculus, at least, the artist and filmmaker Jacolby Satterwhite could be mistaken for a pop star. “I’m having such a Janet day,” he tells me one night over dinner, pulling up a photo of the singer on his phone. In it, Jackson grimaces nervously at the camera. He has just landed in Miami for the 13th annual Art Basel, the art world’s boozy grand fête and celebrity-heavy blowout. His new autobiographical film, En Plein Air: Diamond Princess, which continues the artist’s inquiry into the nature of the body, will premiere in late April at the Pérez Art Museum, and I’m curious what else he has planned for 2015. Satterwhite, who’s wearing a T-shirt that reads just hype, pauses and sets down his beer.

Born in Columbia, S.C., in 1986, Satterwhite was schooled at a young age in New York’s distant club culture by his two older gay brothers, both of whom spent time in the city’s party scene, bringing back dance tapes they’d heard at venues like Area and Limelight to play at family picnics. (Videos of these family gatherings, recorded by his father, later served as material for one of Satterwhite’s first films, The Country Ball 1989–2012.) Satterwhite listened to the tapes endlessly while growing up, and they became important reference points for his growing aesthetic coordinates, which ranged widely — from Caravaggio in the 1590s to Janet in the 1990s. He also established an early archive of images and sounds sourced from his family that would inform much of his later work. From his brothers and their life in New York, Satterwhite learned a critical — and distinctly queer — sense of style. “They cared about Thierry Mugler, fashion, clubs, and the city. I basically learned what it means to be gay by the time I was eight.”

Satterwhite first began to make art seriously in high school, studying painting at a small institution in Greenville, S.C., before heading to Maryland Institute College of Art. His 2008 graduation thesis drew from a collection of sketches by his mother, Patricia Satterwhite, that he’d recently discovered. Over the years, Patricia — who suffers from schizophrenia — had become increasingly obsessed with the Home Shopping Network, convincing herself that she, too, could be an inventor of handy, best-selling objects. She began to produce schematics of her ideas, but her “inventions” became recognizable the more she produced them: grills, vacuum cleaners, diamond rings, toasters, even dildos. While at MICA, Satterwhite organized the drawings into an archive, copying some of the images into his own paintings. Encouraged by his professors, he continued to incorporate her work into his, “collaborating” on a thesis that focused on sexuality and object relations. He again merged his mother’s work with his own at the University of Pennsylvania, where he received an MFA in painting in 2010.

After graduating from Penn, Satterwhite began to experiment with new technologies to expand his practice beyond the canvas, beginning with Adobe’s After Effects. Finding the program clunky and insufficient, Satterwhite taught himself Maya, an extremely difficult 3-D rendering software that allowed him to digitally animate the prismatic spaces he used to paint.

“It’s about spatial terrain, the freedom to sculpt and craft spaces dynamic enough to combine my mother’s work, my live performances, and as much else as possible,” he explains. “I can make any moving image I want.” Using Maya, he rendered his mother’s drawings into glimmering videos, including The Matriarch’s Rhapsody, which was later screened at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Using Maya, he began to animate longer video pieces that combined live-action footage of himself performing in the streets. These animated videos dealt with imaginary urban architectural spaces consisting of highways, towers, transit systems, and forests, incorporating live images of him as his world’s tiny, singular citizen. Satterwhite started painting less and reoriented his process toward animated film, eventually dropping the brush altogether.

I first met Satterwhite in SoHo in fall 2013 at a café outside his studio. It was during his residency with Recess, a nonprofit arts organization that promotes “everyday interactions between artists and audiences.” Standing in Recess’s large open windows facing Grand Street, Satterwhite waved passersby into the studio, inviting them to do whatever they wanted in front of a green screen. Nervous tourists danced, babies crawled, a very well-hung man got naked. Satterwhite performs publicly — and in his videos — in darkly psychedelic bodysuits, usually with small screens sticking out of plastic appendages from his crotch and head that play versions of his films. For anyone walking by his studio and seeing him standing alert in the window in one of these outfits, he must have seemed crazy, but irresistibly so. Many, many went in.

Satterwhite is slight and usually colorfully dressed in leather, gold, rhinestones, and graphic T-shirts. (I once saw him in a sweater partially made of baby blue ostrich feathers.) He laughs a lot, though mostly at his own expense: He likes to refer to himself as Charlie Brown, and in some sense the cartoon character’s devotional and charming sweetness mirrors Satterwhite’s own. His humor, however, is uncannily honest, and usually directed at his own attempts to navigate the absurdities that come with a career in the art world: pushy gallerists, dubious opportunities, late payments, and dogged writers. For Satterwhite, everything is quite hilarious — a sensibility that makes him both open and accessible.

While at Recess, Satterwhite began work on Reifying Desire 6: Island of Treasure, his most accomplished and exhaustive work to date. Like the other films in the series, Reifying Desire 6 is densely literary, generating out of his mother’s drawings a dreamy architecture of profound psychological depth, and elaborating out of ostensibly nothing a locomotive-like network of bodies and places, objects and language. Linked by an intricate transit system, the volunteers filmed at Recess can be seen riding the subway throughout the film.

Reifying Desire 6 achieves a terrifying poetry, focusing primarily on birthing processes that the artist visually analogizes to the cancerous production of cells, situating himself as a mother-producer in an imaginary city of seemingly endless neon glow. For the film, Satterwhite hired the porn star Antonio Biaggi — best known for his work with Treasure Island Media, hence the film’s subtitle — to perform a mock fuck session. Footage of the two humping one another glimmers and coils around the various complex structures that appear in the film, populating trees, arches, and highways like flowers. At one point, Rihanna makes an appearance, her head tilted back as she blows smoke into the air. The film concludes with the artist lying with Biaggi on the grass, looking at an egg that eventually shatters, transforming into a spinning pagoda.

The film heavily references bodily functions gone awry. Cellular objects mutate, expand, and intoxicate the various systems of its world, collating into bodies that break apart — and down. This particular theme mines Satterwhite’s own experience with osteogenic sarcoma, a bone cancer he battled when he was 11. The cancer went into remission when he was 12, but it returned when he was 17, destroying his right shoulder muscle and depriving him of most of his right-arm movement. Toward the middle of Reifying Desire 6, Satterwhite uses his left arm to assemble a being out of cancerous-looking cells and plants, hanging it from a tree as it begins to contort and dance.

Photograph by Aingeru Zorita. Styling by David Casavant

The curator Stuart Comer later included the film in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. While the Biennial received mostly tepid reviews, Satterwhite’s film earned consistent praise, culminating in an appearance on Charlie Rose with Zoe Leonard and Comer.

In Miami, Satterwhite shows me the first few images from En Plein Air. “The film is about violence and erasure, mostly the opposite of Reifying Desire 6,” he tells me as he flips through the stills on his phone. In the film, large white men rape and repeatedly destroy the artist’s body, a systematic display of violence that continuously undoes him in ceremonies of control, conducted by the rapper Trina, whom Satterwhite filmed in his Miami studio in summer 2014.

Like his other videos, En Plein Air takes place in a series of architectural platforms that are assembled into an imaginary, moving city. Visually, however, the film differs in its breadth and intricacy, making use of a darker color palette than his previous works. The platforms where the bulk of the film’s action occurs are connected with flowing braids of hair, which float across a backdrop of fractal clouds and shimmering bursts of light. He’s already spent five months on it when he shows me the first still, but it isn’t near completion. “That’s all I can show you,” he says. “It’s just too unfinished.”

Throughout the week of Art Basel, Satterwhite and I jump from party to party, spending the afternoons at various meetings and lunches — or hungover in a hotel room. Occasionally, we discuss Ferguson, Mo., where rioting over the non-indictment of Darren Wilson in the killing of Michael Brown had been raging. In the art world, the lack of much of a response — or even any interest — seems deafening in South Beach’s densely packed bars. The sweaty, cokey atmosphere of the party rage feels terribly out of sync with the rest of the country, where “rage” retains its original meaning. In Miami, we drink for free and watch Miley Cyrus perform. In New York, Oakland, Ferguson, Chicago, and elsewhere, they march.

I never hear Satterwhite compare himself to Cyrus, and he doesn’t seem to put much stock in her career, but when the show ends and a few friends begin to grumble about the quality of the performance, he is quick to defend her: “She’s just young and nervous and high. It was cute!” I tell him I think Cyrus’s use of a black woman as a performance prop is dubious and unsettling. He waves it off: “She’s just young.”

Satterwhite’s own performances often reach the frenetic, if somewhat confusing eclecticism of Cyrus’s, and they’ve faced similar criticism. The chaotic mix of dancing and audacious audience engagement can be bewildering. (Satterwhite sometimes pulls in random people to dance with him, shoving his face in their crotches and stripping them of their pants and shirts if they consent.) “I always lose half my supporters when they see me perform,” he told me once, after he’d danced for M/L Artspace in Bushwick, Brooklyn. “But then again, I usually pick up a new audience, too.”

Later, over drinks in the Delano’s palm-lined backyard, I ask Satterwhite if he thinks the art world has a race problem. We are surrounded by hundreds of predominantly white collectors and curators.

“Yes. It’s the problem I’ve never not known. It’s hard to even think about it.” During the Whitney Biennial, HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, a collective of black artists and writers, withdrew from the show, partly in protest against the inclusion of Donelle Woolford, a black female artist who happened not to be real — she was actually the invention of a white male artist, Joe Scanlan, who makes work “as” a black woman. For many, the inclusion of Scanlan marked a low point for American museum culture, which still disproportionately privileges white males over anyone else.

For Satterwhite, this privilege, which is often felt on a smaller, micro-aggressive level, suddenly loomed large, souring some of the Biennial’s better coverage, including his own. At the time, he didn’t know how to respond. Neither pulling out nor making a public statement felt like viable options, and the result was a troubling silence on his part. Satterwhite regretted it, and resolved to make his next project — En Plein Air — a meditation on institutional violence and race.

Often, the art world’s aggressions feel very focused. While talking with a group of artists at an opening on the Lower East Side in mid-December, a week after Art Basel, Satterwhite stood mostly quiet, his arm raised to dangle over his head, a signature, though idle, move he often makes when he’s anxious to talk — or otherwise move on to something else. A white artist approached the small crowd around him and said with a laugh, “Hands up! Black lives matter!” We were silent. Satterwhite stood there quietly, almost amused at the absurd — if unexceptional — theft of the phrase that had been echoing throughout the city. Online, right-wingers, cops, and the aggressive supporters of cops had been poking fun at the phrases, altering their meanings to grim political effect: The pro-police hashtag #ICanBreathe was trending on Twitter. Satterwhite wasn’t shocked. It was behavior he had seen before, at other openings, at other galleries, here and elsewhere.

Someone told the white artist to “fuck off,” and he did.

Photograph by Aingeru Zorita. Styling by David Casavant

Throughout the 1990s, Patricia Satterwhite produced a body of work that Satterwhite has yet to incorporate into his own: eight pop albums recorded using a tape player in her home. In his studio one afternoon, Satterwhite plays me some of her album Healing in My House. We listen to a few tracks, repeating one, “Model It,” several times. “Put on your best dress and go model it,” Patricia sings over a jangly, synth-heavy house instrumental that Satterwhite later added. “Pull yourself together and put it all on / You’re going to a place where pretty is known / We’re going to put it to the test.” It is a gorgeous, sweetly sincere song, a parenthesis of hope and calm in Patricia’s otherwise turbulent output. We play it a few times before Satterwhite stops the tape. “I tried to use this for some videos in 2008 and 2009,” he says. “But it was too heavy. It’s full of so much hope. I might revisit it one day — to actually have my Rihanna moment — but then again I may never use it again unless the art overpowers the heaviness of it.”

He shows me a two-channel video he had made using “Model It.” In it, Satterwhite vogues around Manhattan’s luxury store windows and limousines at night, dressed in one of his bodysuits. He points and gestures toward the various displays of upscale goods, darting across town while the camera shakily follows him. A mask attached to his suit covers his face, transforming him into a shadow dancer ghosting Manhattan’s empty streets. He imitates the advertorial logic of the displays, modeling their presentational format with his arms, framing the objects to the soundtrack of his mother’s singing. “I gotta put myself together,” she declares, her voice gaining momentum just as Satterwhite leaps in front of a Versace store. I laugh. Satterwhite turns to me and smiles. “I know,” he says, and looks back at the screen, where the letters of the Versace logo flash gold in the night.