- Source: ART NEWS

- Author: Brian Droitcour

- Date: APRIL 15, 2016

- Format: DIGITAL

Past and Future Camera: Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin’s New Movies

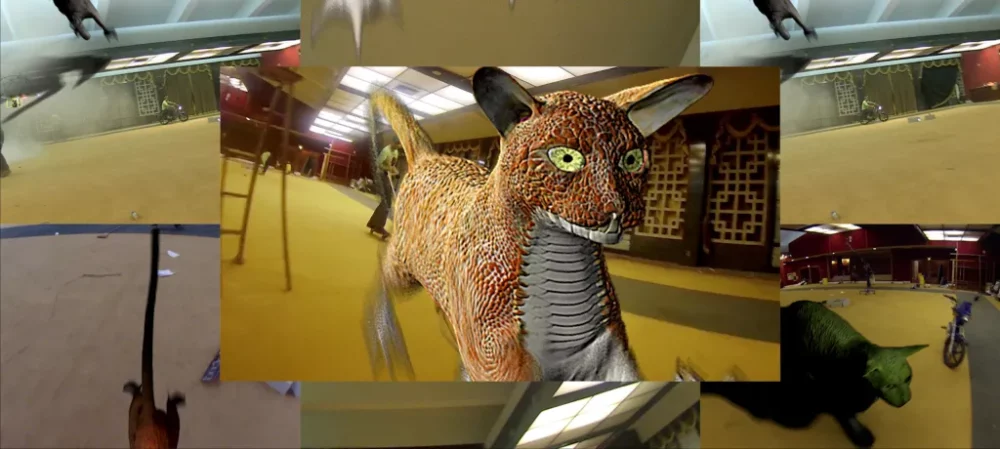

Ryan Trecartin: Mark Trade, 2016, single-channel HD video, 1¼ minutes. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

A nervous girl is sitting and fidgeting in a room. “Can you tell the difference between a camera and a camera?” asks an off-screen voice. The girl breaks her downcast gaze to furtively glance at the two cameras recording her. “Yes,” she whispers. This is one of the first scenes in Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin’s twenty-minute movie Permission Streak (2016). The question of cameras and the differences between them is one that Fitch and Trecartin may have asked themselves while editing their latest works. They used to shoot with one camera at a time and simulated a multiplicity of perspectives with montage. But in recent years their shoots have involved several handheld digital cameras, as well as drones (operated remotely by Fitch), and GoPros attached to actors’ bodies.

Permission Streak and the three other works in the “Site Visit” suite (all 2016), on view at New York’s Andrea Rosen Gallery through April 20, have all the hallmarks that Fitch and Trecartin’s movies are known for: disorienting editing and fragmented narratives; soundtracks with heavy bass and ambient noise; garish pancake makeup and K-Mart collage costuming; dialogue that sutures familiar colloquialisms and dictions into an alien creole; and the sculptural screening rooms constructed for gallery presentations, which use furnishings from Ikea and the Home Depot to remix the generic domestic environments where other audiences might be watching the same movies over the Internet. But the proliferation of footage sources is one of several stylistic innovations that make new movies like those in “Site Visit”—Temple Time, Permission Streak, Stunt Tank, and Mark Trade—strikingly different from earlier ones by the artists, who have been collaborating for fifteen years. Scenes have been shot outdoors using natural light. Some of the actors wear little to no makeup, and chose outfits from their everyday attire instead of donning ones designed by the artists and their crew. Earlier movies were carefully scripted, but the new ones include Trecartin’s directorial instructions, actors’ spontaneous commentary, flubbed lines, and physical bloopers. There’s also more physical movement. In the breakthrough suite “Any Ever” (2009–10), characters sat in one place and delivered monologues, but in “Site Visit,” they walk, explore, and perform stunts. Temple Time has GoPro footage of skydivers in freefall. Segments like this made the exhibition at times feel like the artists briefly leaped out of the tightly constructed world of their art for a gulp of fresh air.

Many of the new developments in “Site Visit” were first introduced in “Priority Innfield,” a set of four movies that premiered at the 2013 Venice Biennale. They were inspired in part by Trecartin’s rediscovery of camcorder footage he shot in high school, which he edited into Junior War (2013) and released along with “Priority Innfield.” Junior War shows teenagers grappling with the oppressive freedom of white Midwestern suburbia. They tool around in minivans, vandalizing mailboxes, and strewing lawns with toilet paper. They confront the cops. They experiment with drugs and alcohol at house parties and raves in the woods. When Trecartin watched his old footage it struck him as a time capsule of obsolete attitudes toward being filmed. If high schoolers today are in the habit of sharing their downtime on Snapchat, in the nineties encountering a camera at a party was a surprise. (“Ancestors weren’t capture ready all the time,” as a character in Temple Time says.) Cries of “stop filming me!” and “don’t point that at me!” sound as a litany throughout Junior War. While the kids protest at first, Trecartin keeps his camera on them until they relax. One boy smiles, then looks nervously to either side, and then, indifferent, picks his nose. A girl who initially doesn’t want to be filmed confides to the camera once she’s drunk. Junior War is about adolescents testing the limits of their social environments and of their bodies, while simultaneously negotiating an unfamiliar regime of surveillance.

Each body of work that Fitch and Trecartin have produced—sometime between the filming of Junior War and its postproduction—feels loosely affiliated with a certain genre of camerawork. A Family Finds Entertainment, 2004, is redolent of home videos made by kids with camcorders—as if Trecartin’s high-school habits of cinematography lingered at the back of his mind even as he tried to invent new ones. The videos included in “Any Ever” (2007-2010) use the frontal directness of Skyping and vlogging, imagining the webcam’s lens as a means by which selfhood leaks into otherness and vice versa. Though the works Fitch and Trecartin have made since moving to Los Angeles in 2010 retain those flavors of social media and DIY video, they have more to do with Hollywood’s broadcast media. Most have been shot on a Burbank soundstage, or on location. The multiple people named Jenny in Center Jenny, 2013, part of “Priority Innfield,” run around screaming as they compete for an obscure prize, like contestants on a game show or reality TV. Temple Time feels more cinematic. It was shot in an abandoned Masonic Temple on Wilshire Boulevard, which the Marciano brothers (of clothing brand Guess) bought to house their art collection. They let Fitch and Trecartin run wild in the derelict space until renovations began in spring 2014. The temple’s urban ruin is a wilderness to Temple Time’s characters, who fill a cavernous, windowless ballroom with tents and bug out like they’re at Burning Man. The way they explore the dilapidated interior’s various levels recalls horror movies, action movies, and adventure shows for children.

In a conversation last week, Fitch and Trecartin told me they think of the LA works—both in “Priority Innfield” and “Site Visit”—as being about gaming. While the exploratory mode of Temple Time has an affinity with fiction film, it also mimics the behavior of video-game avatars: seeking objects, identifying their purpose, finding the rules and limits of their world. (Rhett LaRue, who has acted in Fitch and Trecartin’s movies and worked extensively on their postproduction, has built a 3-D model of the Masonic temple using game-design software, and the artists plan to make a video game.) That orientation determines the characters’ attentive relationship to everything directly outside their bodies. They talk about what they see more than what they feel. That’s what makes the “Site Visit” movies different from “Any Ever,” where characters explore and transform their inner worlds by externalizing their imaginations. And if Trecartin’s high-school classmates in Junior War were actively, even violently, engaging with their physical environment yet timid and passive about being filmed, the characters in Temple Time are all too familiar with cameras but feel lost and amazed in the world.

“How did this get here?” is to Temple Time what “Don’t film me” is to Junior War—but in Temple Time the characters are the ones who created the situation they’re in even if they don’t remember doing so. Everything is always new. “I went in the basement and I saw something so I got his camera,” one character, played by Trecartin, says, pointing to a GoPro on his head. “I’ve never used a toilet before,” says a guy loitering in a bathroom stall. In one of the tents in the ballroom-forest, a woman says: “It feels like someone is watching us.” She’s wearing a contact mic. The guy beside her says: “I’ve been filming you with this camera I just found.” The way the characters of Temple Time move through their surroundings seems to double the way Fitch and Trecartin make art. The habits and modes of behavior catalyzed and normalized by cameras, by social media, and by reality TV have, in the artists’ eyes, hardened into artifacts. Those norms belong to a cluttered media environment where they exist as parts that the artists can observe with wonder, use, and discard before continuing to explore.

Ryan Trecartin: Temple Time, 2016, single-channel HD video, 49 minutes. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

Ryan Trecartin: Stunt Tank, 2016, single-channel HD video. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

Ryan Trecartin: Temple Time, 2016, single-channel HD video, 49 minutes. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.

Ryan Trecartin: Stunt Tank, 2016, single-channel HD video. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York.