- Source: THE NEW YORKER

- Author: Peter Schjeldahl

- Date: JUNE 27, 2011

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

PARTY ON

Ryan Trecartin at P.S. 1.

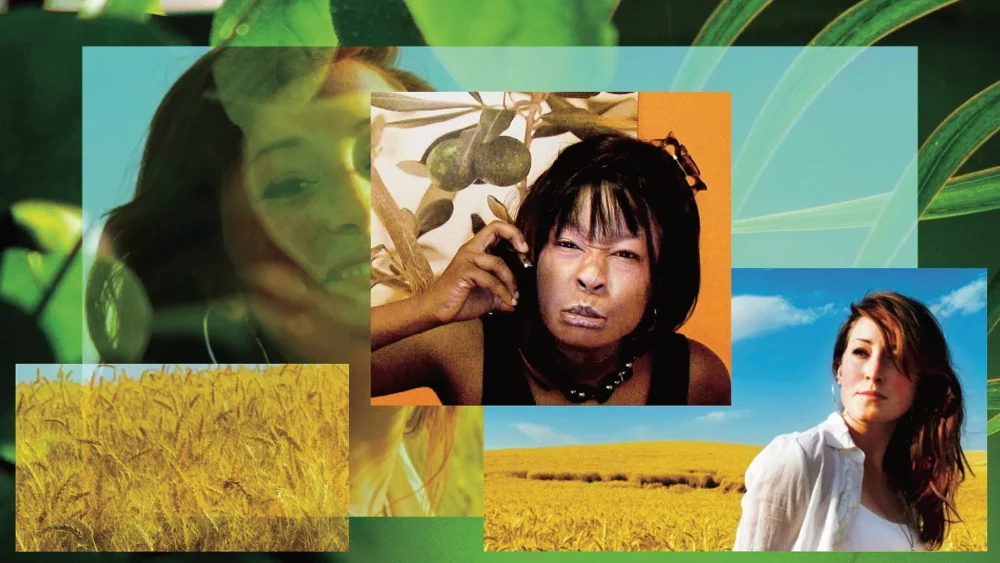

Fast forward: a shot from Trecartin’s video “Roamie View: History Enhancement (Re’Search Wait’S)” (2009-10).Photograph COURTESY MOMA P.S. 1

“Ryan Trecartin: Any Ever”—four hours’ worth of seven looping videos, projected, at P.S. 1, in rooms featuring ambient music, eccentric seating arrangements of Ikea furniture, and a party atmosphere—demands, or, rather, clamors, to be seen. It’s an exhilarating onslaught, loaded with bizarre charm, of fast, noisy, animation-enhanced performances by a cohort of uninhibited young folks, shot over a year and a half, mostly in a humdrum house in Miami, and finished last year. The show affirms a craze among many in the New York art world for Trecartin, the Texas-born wunderkind, now thirty. The furor took hold in 2008, with his triumph in “Younger Than Jesus,” an international roundup of young artists, at the New Museum. To put it simply, Trecartin—aided by his close collaborator, Lizzie Fitch, and a revolving cast of often cross-dressing cutups, starring himself—is the most consequential artist to have emerged since the nineteen-eighties, when Jeff Koons inaugurated an era of baleful glitz. Trecartin, making a big, sophisticated, operatic art of YouTube styles and sensibilities, is being hailed as the magus of the Internet age. I’ll subject that statement to some skeptical due diligence, but first I’ll go it one better: Trecartin slices through the art world’s bondage to commercial and institutional powers. Making his videos free for all, on Vimeo, he aggregates a self-selecting audience of the interested. Galleries, museums, and movie theatres are just more sociable options for presenting his work. You feel this at P.S. 1: for now, the moma affiliate is Trecartinland.

Trecartin has never lived in New York. Born near Houston, he moved at the age of six with his family to suburban Ohio. His father was a steelworker who now manages a recycling plant; his mother was a substitute teacher. He had to repeat the first grade, which made him older than his peers in the high-school class of 2000. He has said that he always loved organizing games of playacting with friends—his specialty to this day—and that he was aware early on of being gay, but that news of the aids epidemic made him shy of sex. It takes a while, watching his videos, to realize that, though they appear to suggest orgiastic goings on, they actually display little or no sex, nudity, drink, drugs, smoking, or, except for the odd smashed glass or bric-a-brac, violence. Without the abundant vernacular profanity—which is speeded up or echoed, becoming largely unintelligible, like nearly all of Trecartin’s scripted dialogue—the work would warrant a PG rating. He made his first distinctive piece as a video major at the Rhode Island School of Design, in 2004: “A Family Finds Entertainment,” in which a distraught boy at a houseparty locks himself in a bathroom, cuts himself with a knife, runs outside, is hit by a car and killed, and then is resurrected to rejoin the revels. Trecartin has not since written a plot as coherent as that one. You go with the cascading flow, viewing his videos, or you’re lost and alone.

After graduating, Trecartin moved with friends to New Orleans and set to work in a house that, a year later, was destroyed by flooding from Katrina. He was in Philadelphia when his video “Sibling Topics” débuted, in the “Younger Than Jesus” show. One plot, or plotlet, involves two sisters in a set of quadruplets who oblige their father’s preference for triplets by merging into one. (Or so I read; with Trecartin, story matters less than what may be termed “storyness”—a Rorschach-like quality of seeming to agree eagerly with whatever interpretations occur to you.) He now lives in Los Angeles, and, wouldn’t you know, he has been befriended by James Franco. In person, Trecartin is confident but unassuming, polite and open-faced. Although he chooses to remain on the fringe of the art world, he says that he likes it, as a realm “where people attempt to be able to do anything, as long as they can create a context for it.”

His context, it seems, is culture at large, with no distinction between high and low. In his work, it is neither critiqued nor satirized but “digested.” His all but incomprehensible scripts are spattered with buzzwords from technology and business but veer steadily into nonsense. Here’s an atypically cogent nugget: “Guys I just Wanted to show You Your New Office! Health Care, I don’t Care, It’s all we Care, That’s Why we don’t Care. this is global!”

Trecartin’s videos are gloriously funny but rarely permit laughter. In effect, they are rapid-fire successions of punch lines with no setups. Any shot lasting more than two seconds feels leisurely. Outlandish wigs and makeup, including painted teeth and varieties of skin color, may change in mid-scene, and keeping track of characters—with names like Demo, JoJo NoBrand, and Post-Canadian Retriever Korea—is a tall order. The costumes are mainly off-the-rack mall chic. Most of his characters are women and girls, either born that way or enacted by him and such others as the sublimely talented Telfar Clemens. Many are very pretty; all are piquant, tilting heads and tossing hair while hectoring the camera or one another. (In Florida, Trecartin availed himself of the vast pool of young performers who sing and dance, or aspire to, at Disney World.) Am I not being terribly clear about what happens on the screens at P.S. 1? I’m sorry, but you have to be there, if only online—overwhelmed utterly for a while, then gradually caught up in rhythms, more musical than dramatic, that are very likely to commandeer your next night’s dreams.

Trecartin’s focus, he says, is on individuals exercising “total freedom” to be, behave, and perform as they like. The effects would be freakish if Trecartin acknowledged any social norms, but he doesn’t. In my view, comparisons of him to cinematic masters of anarchic transgression like John Waters and Jack Smith are wrong. His nearest precedent is Cindy Sherman, whose photographic impersonations of people and creatures who are instantly recognizable, though they happen not to exist, relate rather directly to Trecartin’s shape-shifting, goofing, yammering characters. But Sherman’s demonstrations of the mutability of selfhood are reliably disturbing. Trecartin’s are clownish and relentlessly upbeat. This may be a serious weakness. I am unpersuaded by his oft-stated prophecy of a future in which personal, sexual, racial, and all other identities will be masks donned or discarded at an individual’s whim. It suggests a peculiar state of adolescence not just extended but universalized. As a premise for art, however, Trecartin’s determined naïveté pays off beautifully, dropping us down a cosmic rabbit hole into a realm where imagination is interchangeable with reality—a condition partly inspired, he has said, by reality-TV shows, which he likes because they diminish the shame of being embarrassed in public.

Trecartin’s blithely renegade relation to the art world evokes a principle of revolutionary warfare: never mind winning; just don’t lose. Exasperate the enemy. Like General George Washington confounding the British, he exploits the strategic advantage of a limitless hinterland, in his case the digital jungle. Fluidity of personhood—a kind of opened-out, participatory narcissism, with aspects alternately benign and worrisome—is becoming a widely shared, common-sense aesthetic. Trecartin’s affinity to others in his own and younger generations attests to his significance, as an artist who gives form to new intuitions that will unforeseeably but certainly carry social, ethical, and even political weight in the near future.