- Source: ARTFORUM

- Author: Hannah Black

- Date: March 2020

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

OPENINGS: KANDIS WILLIAMS

Hannah Black on Kandis Williams

Kandis Williams, Nathan, 2017, sublimated prints on cotton paper, copper wire, plastic, glass, organic potting soil, 15 × 12 × 9".

IN THE MYTH OF EURYDICE, she dies from a snakebite while in flight from a rapist god and goes to the underworld. The underworld here, in Greek myth, unlike in Christianity, has no moral meaning. Life and death are collaged together: Even the dead have to live somewhere, once they are no longer alive. Eurydice’s wannabe rapist, Aristaeus, is a minor god, associated with pleasant everyday things like honey, cheesemaking, and medicinal herbs. Eurydice is hounded to death by the representative of home comforts: That’s her fate, and not hers only.

Eurydice’s husband, Orpheus, is heartbroken. Nymphs hear his mournful song and are so moved they send him to the underworld to retrieve her. They give only one condition: While leading her back up to the surface, he must not turn around and look at her. The rule, like the one about the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden, contains its own transgression and therefore fulfillment, as if narrative were born from broken places in the law. Orpheus is compelled to turn toward Eurydice, and in doing so banishes her back to her permanent death. (It could be worse; in The Odyssey, as Circe observes sympathetically of Odysseus, “other men die once; you will have died twice.” On safari in the underworld, Orpheus doesn’t seem to consider how Eurydice might feel about dying twice over.)

Kandis Williams, Viola, 2017, sublimated prints on cotton paper, copper wire, plastic, glass, potting soil, 10 × 13 × 11".

Across performance, video, sculpture, painting, photography, and collage, Kandis Williams’s cluster of Eurydice works, 2018–20, stage Orpheus’s destructive backward gaze as a problem of relation as such, especially, though not only, in the context of black performance. Williams’s close attention to what she often refers to as the “scopic regimes” of meaning reveals that, like Orpheus’s longing/killing glance, the gaze negates what it desires. This unreal gaze is the folk belief of a culture that believes in the destructive power of looking. Since the abolition of gods, Williams’s work suggests, this once divinely mediated power has curdled into secular—in both religious and economic senses—harm. It traverses the real violence of social systematization, a falling bridge, a second death. Though aroused like an apex predator by signs of vitality, it transforms everything it touches into inert material. This essentially psychoanalytic problem has been given new urgency by a phase of high-speed mass communication in which all aspects of the social feel riven, like an embarrassing dream, with the manifest content of race/gender. The unprotected substrate undergirding civil society has been frothed up into a torrent of poor images and rich returns.

The unprotected substrate undergirding civil society has been frothed up into a torrent of poor images and rich returns.

As the theorist Maurice Blanchot says, Orpheus “wants to see [Eurydice] not when she is visible, but when she is invisible, and not as the intimacy of a familiar life, but as the foreignness of what excludes all intimacy, and wants, not to make her live, but to have living in her the plenitude of her death.” The pseudopolitics of art draw the artist into the orbit of an extractive demand that she express her death’s vitality. She is asked, implicitly, to report back from the underworld, to be both dead and alive. Williams deploys exaggerated tropes of beauty/desirability to both emphasize and evade this demand, transposing it from one form of visual obscenity (death, death, death, multiple deaths like a demigod) to another (sex, sex, sex, like the exact opposite of a perfect mother). The sculptures in her 2018 show at Los Angeles’s Night Gallery, which was also titled “Eurydice,” are vases of artificial flowers printed with, in her own words, “black porn stars that my non-black exes loved, and white cocks from a website called whitecocksupreme.com.” One is additionally decorated with one of Williams’s occasionally extravagant titles: I have everything but respect for you bouquet: Erica orchids, My so called lilies and People talk bad about Jesus also; the flowers are drinking from a vase of black ink. The undying flowers offer up unborn, static images of pleasure that, as psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott says of the mother’s hatred for her baby, frustrate because they can’t be eaten.

Kandis Williams, I have everything but respect for you bouquet: Erica orchids, My so called lilies and People talk bad about Jesus also, 2018,

Floraform, ink-jet print on chiffon, wire, India ink, vase, 31 × 28 × 24".

In the twenty-one-minute video Eurydice, 2020, the dancer Josh Johnson (a close collaborator and friend of Williams’s) plays a hybrid Orpheus-Eurydice figure, leading the audience along streets and highways, almost disappearing in dusk or smog, gazing blankly or covering his eyes. The video is made up of footage from five different performances from 2018 and 2019. In each, the bodies of the audience line the shifting edges of the performance space; sometimes Johnson walks into them as if into a pliant wall, changing the borders of the informal stage as his witnesses move clumsily out of the way. Blanchot thinks of Orpheus as “he who always dies . . . Orpheus dies a little more than we do.” To die a little more than we do, the performer must find a way to appear more alive. The video’s searching, erratic cinematography seems magnetized to Johnson’s movement, restaging the desiring knot of Orpheus/Eurydice. Blanchot claims that Orpheus “leads and attracts us toward the point where he himself, the eternal poem, enters into his own disappearance, where he identifies himself with the force that dismembers him and becomes . . . the god’s absence, the original void.” The void has no economy, no regime, no meaning. It’s a horizon or disappearing point, a pliant wall.

Previous four images: Stills from Kandis Williams’s Eurydice, 2020, HD video, color, sound, 20 minutes 13 seconds.

Myth expresses a balance of active and passive elements concretized as gender and desire, knotted together by form. This knottiness produces the textural thickness of love/hate that makes the mythic a rich resource for the real. A myth is different from a story because it moves comfortably around the terrain of eternity. The demigod destroys himself, but many times, because he is able to come back to life. In myths, though love and loss exist, death has not yet been introduced with the modern as biological and scientific fact, has not yet been unevenly assigned. In the work of some of the greatest exegetes of modernity—Freud and Marx among them—the myths of the ancient world serve as primordial material, a time before repetition that provides repetition’s fabric.

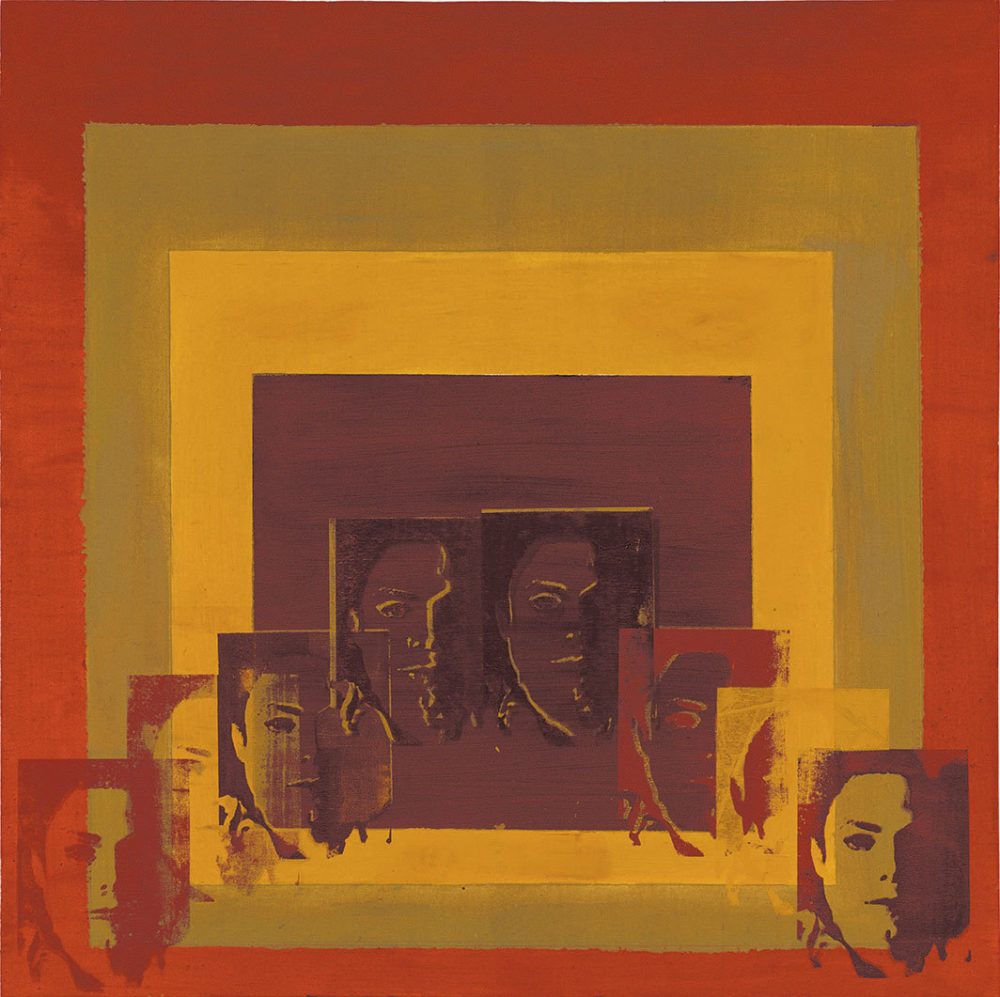

Williams’s editing strategy in the video Eurydice uses this mythic dimension of repetition. Elements repeat across transforming ground: Johnson lies down in one space, and we are immediately elsewhere, with Johnson in the same posture but different audience members looking on. The guarded fascination on their faces—consistent everywhere, that particular way of looking (at a performance) while trying not to look (too hard at the individual performer)—takes on the texture of a landscape; and then the space of the performance fully disappears into footage of roiling lava or burning forest. It is as if the performances had unfolded in a fiery underworld where we’re all politely pretending to be still aboveground. There’s a similar spatial arrangement in Williams’s collages and paintings, such as Primitive accumulation: kant, marx, albers, jackson, 2019: A face repeats several times, morphed or degraded by its assimilation into the fragmentary field of the image as a whole. The wall-based works “open the so-called body and spread out all its surfaces,” as the French theorist Jean-François Lyotard, one of many important influences on Williams’s thought, commands in the first line of Libidinal Economy, 1974.

Kandis Williams, Primitive accumulation: kant, marx, albers, jackson, 2019, acrylic and dye on canvas and board, 48 × 48".

Williams, born and raised in Baltimore, spent more than a decade living in Paris and Berlin and is fascinated by the different inflections of racial fantasy in Europe and the United States. Her work draws together the relational melancholia of French psychoanalytic thought with the semantic intricacies of black American life. She has expressed, in an interview with Emily Mei-Mei Rose for Numéro magazine, that her Eurydice works aim at the anti-revelation that Eurydice “has no face,” that she and Orpheus “have no face to each other.” The social cataclysms of capitalist modernity have produced a model of selfhood that is historically unusual because it is highly individuated and atomized. This is the lost and searching form of self that psychoanalysis attempts to treat: the obsessional neurotic, who asks, “Am I dead or alive?” The hysteric, who asks, “Am I a man or a woman?” Much of the force of what is celebrated and derided as “identity” is, paradoxically, drawn from this pained atomization, as convenient Others come to stand in for a missing Real of embodiment or nature, whether that’s interpreted as pathetic atavism or inspiring survival. “If the sign and the signifier cannot meet, they cannot look each other in the eye. . . . If he really loved her,” Williams has said of Orpheus, “maybe he would have killed himself when she died? But instead he creates form.” Form is the beyond of impossible relation, as the gaze is the beyond of the mask.

Hades, the name of the god of the underworld, means “the unseen.” Though looks of love are objects of longing, it’s being seen while unseen that confirms Eurydice’s place in the underworld, and Orpheus doesn’t think to join her there by other means because he doesn’t want to know he can also die. Don’t look back—or if someone comes promising to save you from your god-given death, don’t follow.

Hannah Black is an artist and writer based in New York.