- Source: Texte Zur Kunst

- Author: AMANDA SCHMITT

- Date: June 24, 2020

- Format: Digital

Notes from Quarantine

THE ALLEGORICAL ACTIVIST

In this time of great forward momentum for the anti-racist and Black Lives Matter movement, social media is a tool of liberation and visibility. Nevertheless, these moments of emancipation do not lie in the medium itself, but in how the medium is being utilized to condemn (rather than celebrate) great violence and fear. In the 15th contribution to our column “Notes from Quarantine” Amanda Schmitt, curator and director of Kaufmann Repetto, looks at the Los Angeles-based artist Kandis Williams’s Instagram feed, which generates a charged media collage primarily focused on reproducing the on-the-fly documentation of protests that are happening every day around the United States. This is not simply a news feed, but Williams’s perspective of what should be news.

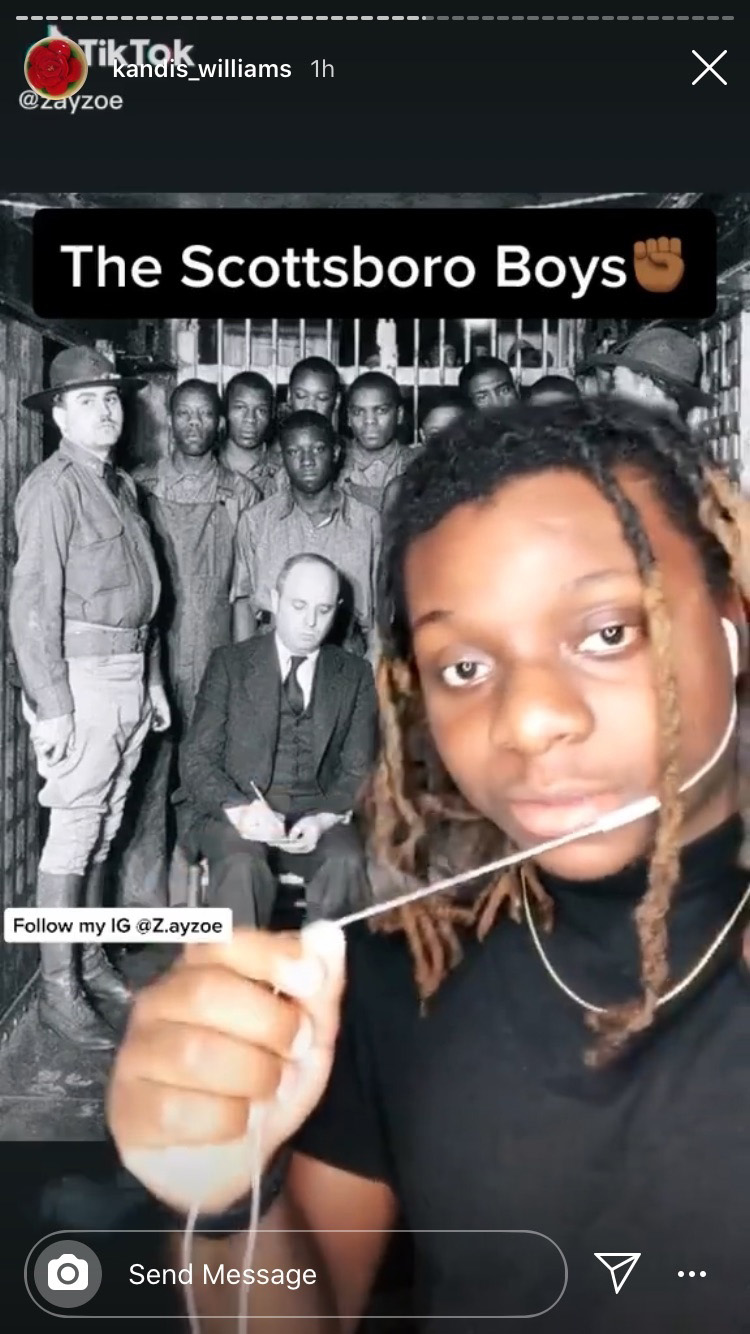

Instagram Story from Kandis Williams, screenshot

“An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of painters, sculptors, poets, musicians. […] And at this crucial time in our lives, when everything is so desperate, when every day is a matter of survival, I don’t think you can help but be involved. Young people, black and white, know this. That’s why they’re so involved in politics. We will shape and mold this country or it will not be molded and shaped at all anymore. So I don’t think you have a choice. How can you be an artist and not reflect the times? That to me is the definition of an artist.” – Nina Simone, 1969 [1]

With the near-total lockdowns that have been ordered worldwide since the spread of COVID-19, iPhone users have undoubtedly received report notifications demonstrating an alarming rise in screen time usage. While ordered by one’s government to shelter in place, those privileged enough to live with the internet or access to data roaming have unsurprisingly turned to their screens to connect with the outside while confined to the inside of their homes. Through the interface of a screen – of laptops, televisions, and phones – many (myself included) have been horrified, even immobilized by witnessing the attempted police and military suppression of actions and events that make up the most widespread global anti-racist movement in history as it’s unfolded since May 25, rippling from Minneapolis outward. We’ve also witnessed millions spring into action, taking to the streets, contributing where they can with their own bodies, to join the protests. Those who have mobilized in physical form made a choice: to defy the 2020 norm of quarantining or keeping social distance in order to stand, arm-in-arm, for another cause they feel is more urgent than the risk of becoming infected with COVID-19 or potentially infecting others. If you are reading this, you have likely turned immediately towards your screens, to look toward artists closest in your community to make sense of these events, to look for direction, maybe inspiration or guidance, through words and images. In order to respond in meaningful ways to “the times” (as Simone describes), some artists take time, whereas others respond immediately, almost as if by instinct, in an instant reaction. Kandis Williams has taken to Instagram.

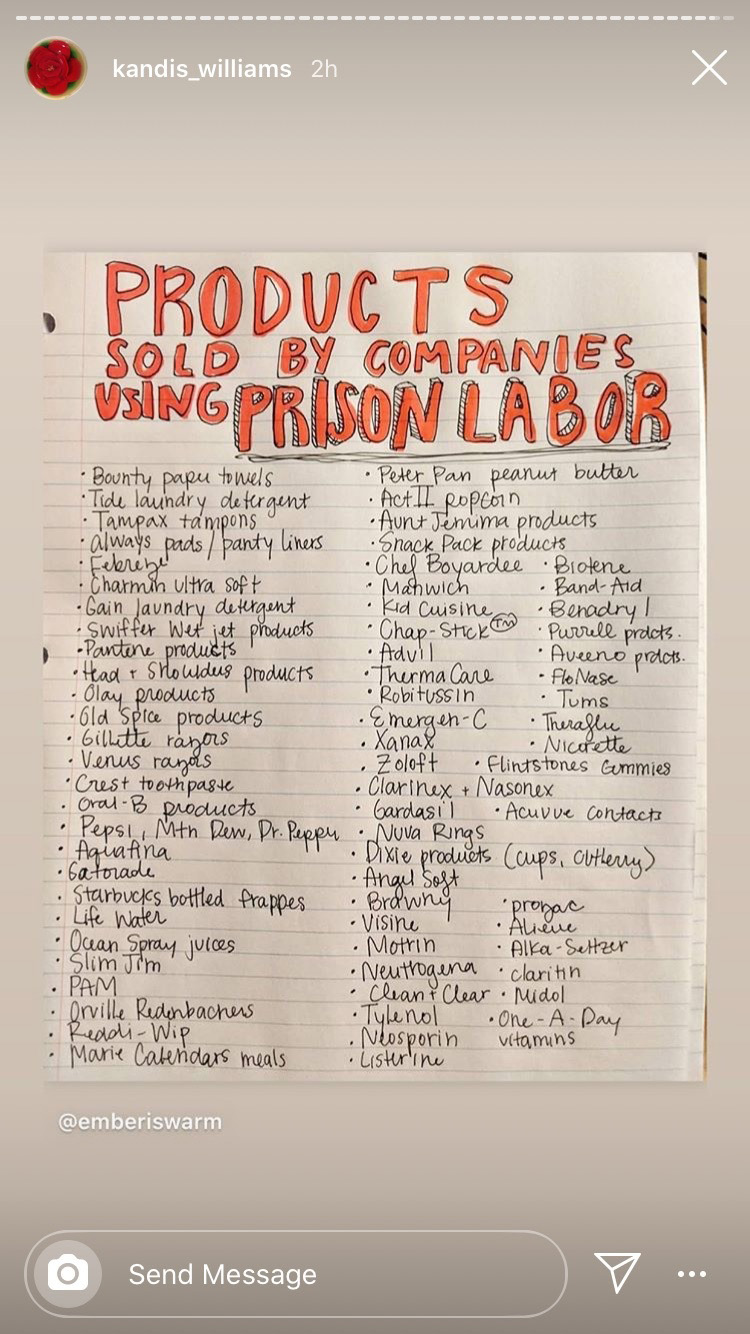

On the Los Angeles-based artist’s feed, via @kandis_williams, she generates a continuous output through the Story function which cements itself as a must-watch feed in a moment of media superabundance. Even the mainstream news outlets have exhausted their resources, reaching peak saturation, but it is still shocking to understand how little these on-the-ground, user-generated videos and images have been reproduced via major outlets like NYTimes.com, et al. Instagram Stories are relegated to a maximum of 100 posts per day, with a limit of up to 15 seconds per post. Within these parameters, Williams is generating a charged media collage with a primary focus of reproducing the on-the-fly documentation of protests that are happening every day around the country. The feed is rooted in depictions of unspeakable acts of brutality by the American police against American citizens, and intertwined with other material including diaristic soliloquies from individuals across cyberspace prompting whoever is listening to get out and take action (protest, march, write your congresspeople, etc.), as well as a mercurial mélange of other timely internet content: instructions on how to protect and care for yourself if attacked by tear gas, state-by-state information about legal rights, and updates about the seemingly daily alterations in law-enforcement procedures (such as curfews and habeas corpus), or tutorials from individuals belonging to or identifying with specific sub-sectors of protest groups – sometimes as specific as the group BLM Witches (who share testimonials and feedback about different spells and hexes that have been initiated). Each new segment is unbelievable: a semi-trailer truck rams through a crowd gathering in the street (nothing is censored); a cop groundlessly sprays mace into the face of a medic who is on-site to help injured victims in need; Gen Z individuals lecture about the threat of fascism in America through the aid of highly-organized fact sheets and charts; a police officer debases a paralyzed man by dragging him from his car and disrobing him; a lawyer explains the for-profit prison system in America; a woman erupts in a meme-worthy song and dance while being unlawfully arrested; and tragically, over and over again we see evidence of cops as they continue to use the knee-on-neck restraint method to detain nonviolent individuals, repeating the trauma of the May 25 murder of George Floyd. Most of all and most affecting is the claustrophobic repetition of unimaginable acts of violence against peaceful citizens, like a nightmare stuck on repeat.

By inverting strategies of appropriation, Williams, in contrast, creates a veritable ideological mode of counter-confiscation (reposting from others’ feeds, across multiple social media platforms) and fragmentation (posting these feeds in short snippets): she proposes a social media millennial update of photomontage as used by George Grosz or Hannah Hoch, or video montage as used by Dara Birnbaum or Arthur Jafa. Whilst Williams is not the first artist to explore Instagram and social media technologies as a tool, a notable departure here is that the material is instantaneous, unmediated, and real: perhaps all too real. While countless artists are indeed on social media, it would be over-broad and precarious to assert that their feeds or posts are their art. Those working with social media technologies (such as Instagram) as their ‘medium’ have traditionally been recognized as ‘making art’ when their subjects and images are obviously or subtly fictionalized, designed, coordinated, and constructed. What is acutely significant here is that Williams demonstrates the art of the ‘repost,’ which although closely related to appropriation, is most adeptly compared to observation and reflection, and thus a form of representation. If we turn to genres in the realm of film or the moving image more broadly, this also relates to documentary (which is never neutral) but is more akin to social commentary. Her form of appropriation confiscates not only images but also the sovereign position of a subject in order to generate discourse even within and beyond the saturation of algorithmic spaces.

Instagram Story from Kandis Williams, screenshot

Williams’s feed, while generated in a seemingly random manner, runs parallel with recent experiments such as Jean-Luc Godard’s 2018 highly-edited film, The Image Book. Godard’s latest work is an 85-minute collage constructed with the aid of assistants, splicing together excerpts from the news, Godard’s own films, other filmmakers’ films (for example Gus Van Sant’s Elephant and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom), documentaries, and (like Williams) a plethora of user-generated content that has proliferated through the internet. The apocalyptic brutality portrayed throughout The Image Book is as intolerable as the format through which Godard stages it: the doomsday editing procedure, in which Godard distorts and renders illegible the film material and desynchronizes the soundtrack, mimics the fragmentary display of beheadings, impalings, maulings, explosions, and burnings depicted therein. The frequency of the violent imagery is merciless – he sticks the finger in the wound. Film critic A. O. Scott’s commentary on the film mirrors my own reflection on Williams’s feed: “The spectacles that thrill us and the documentary evidence that horrifies us are hard to tell apart. Are we looking at cruelty or heroism? Fact or fiction? Justice or barbarism?” [2] The streams of continuous images are utterly unbearable in terms of the horror and spectacle that bombard the viewer, and there indeed exist numerous objections to the reproduction of images of violence, such as that the already oppressed are once again violated by such images. In this comparison, temporality is the significant difference: both are collages made of moving images, although one is simply made more instantaneous than the other. Whilst The Image Book is a sort of melancholic requiem for the image of the broken world that we’ve made, Williams’s feed is the image of the world that’s broken. Both are looking at history, but Godard presumably situates himself in a neutral present that articulates the past, while Williams presents the present with the purpose of altering the future.

As a poignant positional counterpoint in forms of distance and commitment, while Godard dryly narrates his film in a despondent voice grown weary from the 20th century, Williams’s actual voice is absent, yet peppered through instances of comic relief in the feed: a man waxes prophetic (in irony, awe) at a toddler’s scribbled protest sign; a comedian displays a hilariously (and painfully accurate) impression of Trump blabbing about the bible (her position as a BIPOC female makes for a classic contradictory farce); a meme promotes BLM-flavored Doritos chips (calling out the capitalistic impulse to seize this moment); and so on. This is not simply a news feed, but Williams’s perspective of what should be news. Unlike Godard, her authorship is not shrouded in the illusion of distance. The viewer ‘taps through’ from images of peaceful protestors getting rammed by police vehicles or maced at close range, to a much-shared meme of an angelic Breonna Taylor on her birthday, to an armed military officer in his vehicle covertly professing the treason of his comrades in order to directly inform the public behind the scenes; the feed is a rollercoaster ride of ups and downs, inducing a sort of media mania. An outrage montage.

The historian Craig Owens wrote extensively on representation, appropriation, and power. His analysis of the ‘allegorical impulse’ remains a crucial tool towards understanding what Williams is doing now:

“Allegorical imagery is appropriated imagery; the allegorist does not invent images but confiscates them. [S]he lays claim to the culturally significant, poses as its interpreter. And in [her] hands the image becomes something other (allos = other + agoreuei = to speak). [S]he does not restore an original meaning that may have been lost or obscured: allegory is not hermeneutics. Rather, [s]he adds another meaning to the image. If [s]he adds, however, [s]he does only so to replace: the allegorical meaning supplants an antecedent one; it is a supplement.” [3] , [4]

While each and every image or video that Williams reposts to her feed contains electrically-charged affect, her act of reposting layered with the fragmentation and condensation of images coming from all over the world in turn generates new meaning. In many ways her technique is gestural and accumulative: she piles up images ceaselessly, with what appears (daily) to be an inconclusive narrative. Whilst the feed is in fact a continuous flux – and one could say the same thing about social media profiles in general, with their capitalization of the everyday and the present – Williams transcends the simple act of recirculating popular or syndicated media. [5] As a novel alternative, these feeds broadcast a montage distorted through the conditions of its own production and reception. It is a site of redistribution: the images (and thus, information) are reposted within a closed network as a confirmatory act aiming to form a new set of sustainable power relations. Like a chain of calls and responses on Twitter, it is not simply the message that has impact, but the act of retweeting or reposting: the sustained duplication of the tweet or post, reproduced and annotated with comments, propels it forward into the progressive hive mind with new affirmations and interpretations. An important aspect to note is that Williams credits the sources of her images and videos in the feed. [6] At the tail end of many video reposts, the feed cuts to a dark screen with the name of the Instagram or TikTok user. This democratic procedure flips the notion of appropriation on its head: the act of taking another’s feed or image to repost is not meant by Williams to claim as her own, but in fact to emphasize the faith she puts in peer-generated content as ‘truth’ rather than in mainstream media dissemination (which already pervasively contains the threat of fake news or disinformation). Often, a post is prefaced with a variation of “Read this now” or “This is important, this must be seen.” Some of the Instagram users-cum-pundits preface their broadcasts with “the truth must be known.” Whereas urgent proclamations such as these may have once been a telltale sign of conspiracy theories, it is the algorithmic bond of Williams’s community of followers that vouch for these positions. [7]

In this time of great forward momentum for the anti-racist and Black Lives Matter movement, social media is not only a tool of liberation and visibility; it also must be recognized that these tools are increasingly being abused by the right wing. These moments of emancipation do not lie in the medium itself, but in how the medium is being utilized to condemn (rather than celebrate) the moments of great violence and fear. [8] What Williams’s feed thus demonstrates, along with others at this moment, is that the left is finally learning to use the tactics the right exploited to put Donald Trump in power: memes, aggregation, and trolling as a digital forum for politically-propelled debate and action. Dehumanizing reactionary politics was the modus operandi of the alt-right and alt-light in the years leading up to Trump’s election. However, the left can perhaps now appropriate the form of conspiracy theory rhetoric to dismantle and demolish the patriarchal, ossified fortifications that uphold police-state control and white supremacy in America. It’s not ironic that at this moment when all universities have closed their doors (in an effort to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus), the students (and youth in general) have taken to the streets. Here and now, figures like Williams and the cultural and political left are finally reclaiming the guerilla tactics the alt-right and the alt-light had co-opted in the previous decade. This is a culture war; the first battleground was the digital sphere. [9] Its connection to the actual public space, and further, to the legislative sphere, are the two steps that connect Williams’s feed to the future.

In 2017, a young woman named Heather Heyer posted an oft-repeated activist slogan on Facebook before heading to a march in protest of the neo-Nazi Unite the Right rally Charlottesville: “If you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention.” Hours later, she was killed by a white supremacist who rammed his car into the crowd of people joining Heyer in solidarity against the racist position of the rally that had been organized that day. The horrific crash and deadly aftermath were of course recorded and disseminated widely on social media. This image, and many posted on Williams’s Story feed are almost too painful to bear. Why share them? To grab attention, and to prompt action. Why look? Watching the feed is not glorifying: it is a painful act that only multiplies the feelings of anger provoked by these injustices. The debate surrounding whether or not these images should be shared or censored is not a new one, and I don’t have the answer. In the feed, one woman succinctly ends her TikTok presentation with a clear message: “I ask that you share this knowledge, because ignorance is no longer an excuse.”

There is no proper way to depict horror. There is no effective way to demonstrate despair. The transient and sometimes trivializing nature of the Instagram Story medium may even make it feel more consumable, and in turn, more tolerable in the public arena via naturalization. An artist like Williams composes a palimpsest of images that thoughtfully condenses and redistributes these fragmentary images that reflect this despicable moment framed by the Trump presidency. Her Instagram Stories collapse the dominant cultural legitimacy of art and the urgency of activism.

Amanda Schmitt is is a New York-based curator and director of kaufmann repetto.

Image credit: Kandis Williams, Amanda Schmitt

NOTES

[1] Stroud, Andy. Interview from film Nina Simone Great Performances: College Concerts and Interviews, Andy Stroud Inc., 2009.

[2] A.O. Scott, “‘The Image Book’ Review: Godard Looks at Violence, and Movies,” New York Times, January 25, 2019, section C, p. 6.

[3] Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism”, October, vol. 12 (Spring 1980), pp. 67–86.

[4] Brackets added by the author.

[5] Mainstream media is hierarchical and clunky: it only allows the world to move at the pace it sets. With a 24/7 news cycle, this creates a stagnant vacuum chamber. Furthermore, it is not altruistic: it posts to produce clicks, motivated by capital investment alone.

[6] This is in part due to the implicit and automatic repost function generally available to users of Instagram, but anyone willing to spend a little more time on editing or downloading a hack-worthy repost app could easily ‘opt out’ of the repost credit and claim these images as their own.

[7] Often Williams will repost screenshots of other users’ recommendation to follow the @kandis_williams profile. Many of these are artists in our own communities, which leads the readers here to judge for themselves.

[8] It must also be cautioned that although Williams’s feed (like other social media profiles) may appear liberated, or even covert, it is hosted under the auspices of the terrifyingly influential algorithmic power of Facebook, which owns Instagram. We could analyze this debate vis-à-vis Facebook’s recently exposed ‘Community Standards’ which profess to define terms like ‘violent imagery’ in relation to their ability to ‘dehumanize,’ disquietingly ranked by ‘tiers of severity.’ Instagram (in a separate set of ‘Community Standards’) offers an explanation: “We understand that people often share [graphic] content to condemn, raise awareness or educate. If you do share content for these reasons, we encourage you to caption your photo with a warning about graphic violence. Sharing graphic images for sadistic pleasure or to glorify violence is never allowed.” It continues, “When you see an upsetting post, caption or comment on Instagram, consider the larger conversation it may be connected to. Step back and determine the context of the post.” In other words, they urge and require both the use language and the practice of critical analysis when faced with violent imagery. While I am vigorously wary of the emerging hegemony of Facebook and other Silicon Valley conglomerates, we must remain aware that they are the engineers and mechanics that enable this tool, which is being used by communities on every end of the political spectrum (within democratic nations that allow its use, that is).

[9] Further reading: Andrea Nagle, Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump And The Alt-Right (Alresford, UK: Zero Books), 2017.