- Source: Ocula Magazine

- Author: Nicholas Nauman

- Date: July 6, 2021

- Format: Digital

Maintained as a function of Kandis Williams’ multimedia art practice,

Cassandra Press is a publishing platform and pedagogical resource that puts out books and holds classes, workshops, and art residencies.

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

The project is a singularly effective elucidation of anti-Black racism’s persistent structuring of the world as we know it. Best known for an ongoing series of readers that compile wide-ranging texts and images around such themes as ‘Faces of the Colonizer’, ‘Cannibalism, Blackface, and Minstrelsy’, and ‘Double Consciousness Then and Now’.

With classical philosophy, pop culture, and contemporary theory, these readers make obvious the ever-proliferating apparatuses of power that realise classed, gendered, and otherwise fucked-with limits to living that are never not also raced.

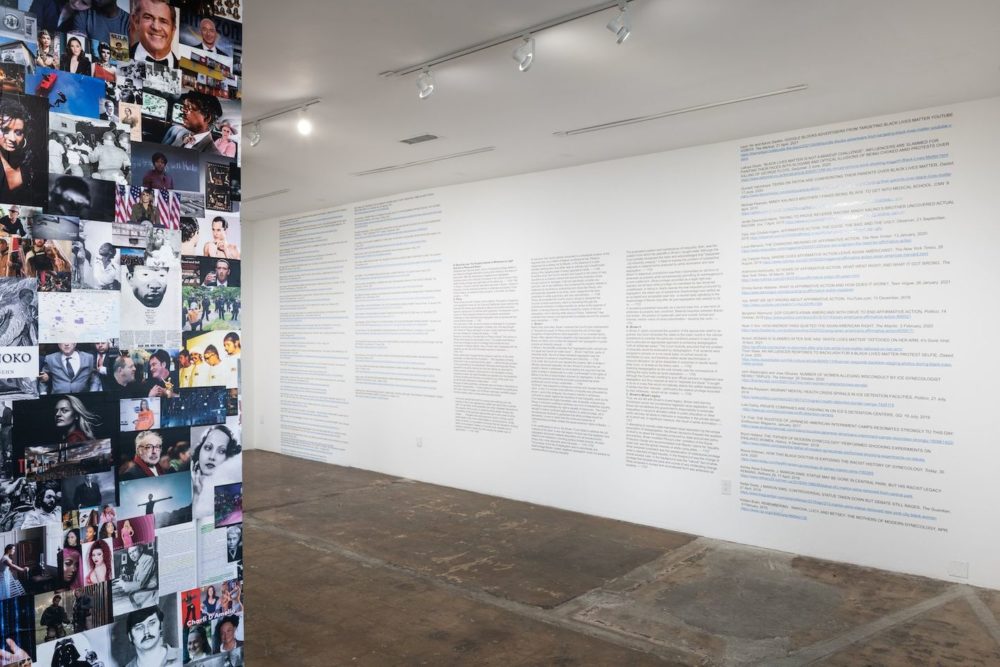

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris’ Whiteness as Property is Cassandra Press’ installation exhibition at LAXART in Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). A facile glance could say the show turns the gallery into a reader. The walls are filled with cut-vinyl text from Harris’ ground-setting 1993 essay, in which Harris describes the legal-historical codification of whiteness according to its supremacist expectations.

Alongside the Harris excerpts are questions that provoke deeper engagement: ‘Is the creation and securing of property inherently violent?’ ‘To what extent does speaking of whiteness as something “possessed” and “guarded” put the sexual purity of white women at the center of Harris’ argument?’

More text, from floor to ceiling, lists web links to other crucial contributions to critical race theory, as well as to articles and op-eds from all manner of media outlets.

Both sides of a wall in the middle of the gallery are covered with hundreds of internet images, pasted over each other’s edges in an intense density of memed celebrities, advertisements, movie stills, and historical artifacts: Kanye West in his red hat, white TikTokers saying ‘I Can’t Breathe’, Marvel heroes, Trayvon Martin, The Great Gatsby, Jesus.

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

In LAXART’s second room, new, perfect-bound editions of many Cassandra Press readers are available for purchase and perusal. People can take home a book of footnotes to the exhibition.

As this description suggests, the teeming text and images could tease a visitor toward feeling subsumed by a world of reference and signification that one couldn’t possibly attempt to know or map totally. Which is the case. You are always already occupying inscriptions of predetermined meaning; the array of words and pictures is less disorienting than properly orienting.

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

As so many scholars, activists, and artists have made clear, race is both a discursively elaborated fiction and an embodied reality. It is a point of conjuncture where the meanings of power sort access to the stuff of life on earth. The Absolute Right to Exclude simply and palpably emphasises the encounter between the visitor’s body and text and image as vessels of historically ordained signification.

To wit, I’m white. I can daily commit to the exhaustive decomposition of the anti-Black world, but the whiteness attendant to my body precedes and exceeds my individuality. The show’s citational spiraling renders me a reference, limning my borders, their porousness, and their entanglements.

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

Harris wrote ‘Whiteness as Property’ in response to the impeded efforts of affirmative action to effect structural change in U.S. institutions. The essay examines race-centred legal cases, from Plessy v. Ferguson to late 20th-century decisions on workplace discrimination, to illustrate the intractability of baseline norms that protect white interests.

Her conclusions are exactingly argued: post-Jim Crow insistence on ‘colourblindness’ just shores up pre-existing conditions that serve whites at the expense of racialised others. Recent white-wing salivation over ‘banning’ critical race theory is pathetic, predictable proof of the theories’ veracity, and Harris’ essay is a classic.

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

Harris begins the article with an account of her Black grandmother, who passed as white for a job at a department store: ‘She came to know [her white co-workers] but they did not know her, for my grandmother occupied a completely different place. […] They remained oblivious to the worlds within worlds that existed just beyond the edge of their awareness and yet were present in their very midst.’ 1

Exhibition view: The Absolute Right to Exclude: Reflections on and Implications of Cheryl Harris' Whiteness as Property,

Kandis Williams, Cassandra Press, LAXART, Los Angeles (28 May–31 July 2021). Courtesy LAXART.

The Absolute Right to Exclude traces the preponderance of these worlds as they manifest in a present which is never without the past. This is no revelation that dissolves the boundaries of whiteness as property; of whiteness as centred axis in the mechanics of global order. That’s all still enshrined in legal institutions, and their structures of allocation continue to affirm white expectations for access to food, shelter, power, and lives that matter.

But with its vast intertextuality and focused inquiry, The Absolute Right to Exclude aestheticises rigorous indifference to the shrouds of linearity and closure that history still tires to impose. The exhibition’s radicality is profound; it is mundane; it shows writing on the wall.

1 Cheryl I Harris, ‘Whiteness as Property’, (Harvard Law Review. Vol. 106, No. 8 : June 1993): pp. 1707–1791.