- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: MIGUEL MORALES

- Date: SEPTEMBER 7, 2022

- Format: PRINT AND ONLINE

Kenny Rivero’s Tricks of the Eye

The artist is creating work that plays with perspective and scale, drawing the background into focus while blurring his own presence.

The artist Kenny Rivero at his studio in the Bronx, New York. Jon Henry

On a sweltering afternoon in the thick of August, the artist Kenny Rivero, 41, opens the door to his Bronx studio. A drum set and some guitars are kept in one corner of the room. Exercise rings dangle from the ceiling. Lego sets share shelf space with a library of art monographs, religious texts and science-fiction novels. His show at Charles Moffett gallery in Manhattan, “Steward: The Ballad of a Super Super,” is opening soon, and his studio is packed with work, though his personal effects also crowd the walls, given the same pride of place as his paintings in progress. There’s the door from his childhood apartment, his old TV from middle school, the curtains from the first place he lived on his own and a raft of fixtures reclaimed from the building where he once worked.

“I definitely need more space,” he says. “I want something clean and empty so I can go in there and make paintings without having to look at everything. But I like this, too. Having a nest.” For Rivero, who was born and raised in New York, “home” is a verb. Across his work, which encompasses painting, drawing, sculpture and collage, Rivero pulls apart and reconstructs the idea of belonging. His art draws on his Afro-Dominican American identity, as well as on a religious upbringing that incorporated Catholicism, Evangelical Christianity, Vodun, Santeria and Afro-Caribbean spiritual practices. This focus not only honors his legacy, it also allows him to challenge the tendency to flatten artists of color into biographical statements. The heritage and belief systems that have shaped him come to the fore, and Rivero himself recedes behind the painting. “It’s hard to avoid sensationalizing the ‘from the streets to Yale’ narrative. It’s part of my life, but I’m making work. Let’s talk about that.”

In just a few months, Rivero produced more than two dozen pieces for his upcoming show “Steward: The Ballad of a Super Super,” at Charles Moffett in New York, though only about half will make the cut. Jon Henry

Rivero doesn’t define himself as a painter. Art is one among many interests, and for a long time he pursued other callings. He applied to a high school specifically for its drama program, first went to college for music and art and then graduated from New York’s School of Visual Arts with a degree in fine art, eventually earning his M.F.A. from Yale. He played in several bands, and had stints as a porter and doorman before entering grad school. “I would cover the graveyard shift all the time and be alone,” he says. “It gave me a relationship to surfaces, to cleaning, and what it means to clean, to renovate and to think about beauty in that sense, too.”

Though he did not consider a career in art until later, he has been drawing for as long as he can remember. Creating these early pictures was “a form of resourcefulness” for Rivero, who was raised on hand-me-down toys and liked wandering the city. His work still evokes the dreaminess and serendipity of a stroll through the streets. He beefs up buildings and figures, makes them look almost distended, just as certain places and encounters loom large in people’s minds. When he mentions the different scales of the paintings in his upcoming show, he might as well be talking about the subjects themselves: “I like mixing dimensions. I want all the paintings to feel intimate, and I feel like the little ones bring the big ones down a bit. In a lot of ways, the little ones feel more monumental.”

“Some of these tools were my dad’s. Some I collected, or stole, from my uncle’s workshop,” the artist says. Jon Henry

Rivero’s breakthrough came in his hometown, at El Museo del Barrio’s “La Bienal 2013: Here Is Where We Jump,” when his art received praise in The New Yorker. Over the past several years, he’s been on a tear, with solo shows in Los Angeles, Mexico City, Arkansas, New York, Vermont and Delaware. Even with a loaded schedule, Rivero does not plan out his work in advance. “There’s something about discovering and improvising that feels really good. I would love it if I was a kind of artist that sketched things out first, but I get bored. It feels like a chore.” For the new show, he’s working against the clock, producing more than two dozen pieces in a few months, although only half or so will make the final cut. Still, he doesn’t feel rushed. “These paintings are so minimal that it’s made me slow down a bit,” he says. It’s fitting that the artist has taken a class on magic, and that he continues to read up on the subject; behind his playful sleights of hand is a rigorous artistic practice.

The sun is fading in the afternoon, and outside Rivero’s window cars crawl across the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge. He slides one canvas out of the way only to reveal another and another, each waiting its turn for more licks of color, a flame or another motif, a cryptic phrase, or an altogether different kind of spell. For now, he knows he doesn’t want to force them to be ready; he’s still playing around. “I never want to fall into that trap of making the same type of painting,” he explains. “Because then what am I doing? Just trying to maintain my wealth? I want to make sure that my paintings are still hard for me to make.”

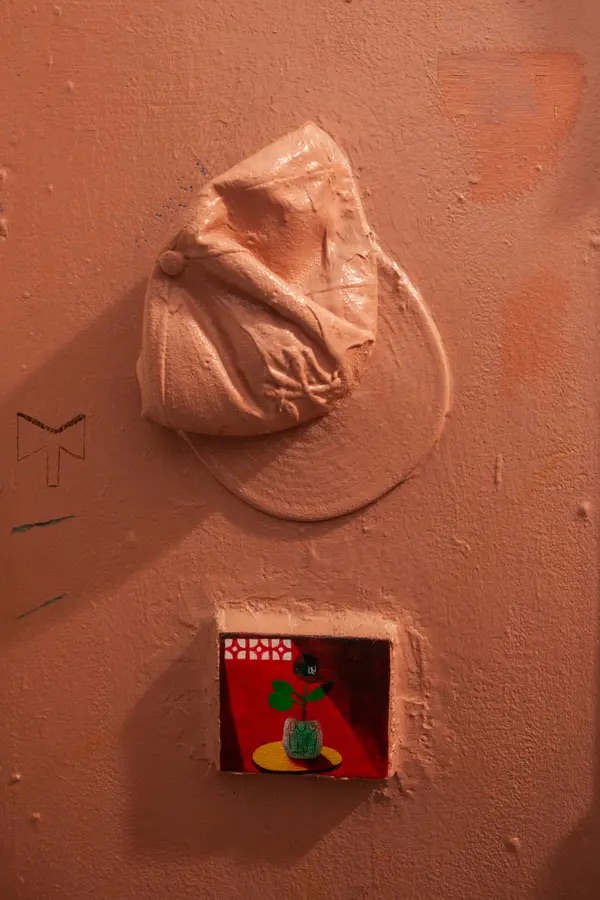

Rivero, who buys salon mirrors and paints over them, has been leaving cryptic markings in his work since he was little, initially to differentiate his drawings from those of the other students in his class. The row of smaller paintings below the mirrors will be included in “Steward: The Ballad of a Super Super.” Jon Henry

What is your day like? How much do you sleep? What is your work schedule?

I try to sleep at least six hours. I usually get here every day around 5 or 6 a.m. I like the streets being empty. Even if I’m not working on anything in particular, I come here so I can get out of my house. I’m thinking about things, developing ideas, looking at my collections, reading my books. One of the first things I do in the morning is sweep. I usually leave my studio a mess from the night before. I’ll organize things and give myself time to think. I like cleaning a lot. I’ll take a break in the middle of the day to shower and then come back and reorganize things.

How many hours of creative work do you think you do a day?

Between nine and 11. If I’m not painting or making anything visual, I’m writing about a painting I’m working on or past paintings, and trying to give myself a chance to think about the work I haven’t spent too much time with. It’s a great problem to have — selling paintings pretty quickly after I make them — but what did I just do? What can I learn from them?

What’s the first piece of art you ever made?

In kindergarten, we went to Madison Square Garden to see the circus. The next day, the teacher had us draw clowns. She gave us these templates to fill in different parts. I remember being so excited about mine I didn’t want to share it. And then we all hung them up on clotheslines around the classroom, and I couldn’t find mine. Mine was so similar to everyone else’s that I didn’t know which one was mine anymore. From that point on I told myself, “I’ve got to put something weird in it, something cryptic, some kind of code, so I can recognize it,” because everything you do as a kid is jumbled up with everyone else’s work. I told myself that was never going to happen to me again.

Even when he’s not actively painting, Rivero likes to spend time in his studio, surrounded by his creations, either reading, exercising or reflecting on the work he’s made. Jon Henry

What’s the worst studio you ever had?

I haven’t had a bad studio. Maybe a studio is uncomfortable, but even then the work has always matched the space I make it in. At least I have a space.

What’s the first work you ever sold, and for how much?

The first thing I sold was for two bucks. Me and my friends used to do drawings in the street and put them out on a blanket. We definitely had this romantic idea of [Jean-Michel] Basquiat going into a restaurant and giving Andy Warhol a drawing. We thought, “Why don’t we do that? People in SoHo are wealthy. They definitely have two bucks.”

When you start a new piece, where do you begin? What’s the first step?

I try to be spontaneous and intuitive and have a conversation with the paint. I usually start with color or drawing, although drawing tends to be a bit limiting because you already have something structured at that point. I try to leave out structure as long as possible and let the material be itself, give it room to breathe — to have a cadence with each thing that I’m painting, an opportunity for discovery, as opposed to me being like, “I’m going to draw a face with a rose coming out of its mouth.” I think that’s boring, so I leave myself room to be more intuitive.

How do you know when you’re done?

I know I’m done when I arrive at a place where there’s nothing I can do to ruin the painting. If I can continue to work on it without throwing anything off its axis, I can confidently step away. When the painting begins to feel stuck in place or too attached to a predetermined plan or idea, I sabotage it and create a new problem to fix. Painting for me is about moving through different phases of editing in response to different ruptures and interventions. Sometimes those moments come from the paintings, but most times they come from me.

Rivero painted over his old Yankees cap and the door from his childhood home, which he recovered from the dump after his mother threw it away. Jon Henry

How many assistants do you have?

I’ve worked with four so far. The first one was a fairly new friend — it wasn’t a good idea. It was hard to be their boss. I work with multiple assistants at once, but I only have one person here at a time. The energy changes when there’s three people here. I did that for a week but it didn’t work out, so I just keep two assistants, whom I rotate. But the best assistant I had said, “I’m not doing this anymore. I want to be a painter.” Go for it! Hell yeah! Quit!

What music do you play when you’re making art?

Sometimes jazz, sometimes hip-hop, sometimes soundtracks and other cinematic things. I also like to play podcasts. I watch a lot of movies. One’s usually playing in the background. But sometimes dialogue and lyrics get in the way of painting, so recently it’s been a lot of instrumentals. And talk radio — I can ignore that.

Tessellated printing blocks that someone from Rivero’s building was throwing out. Jon Henry

When did you first feel comfortable calling yourself a professional artist?

In undergrad, I had to develop an ego — an aggressive ego — because it was so competitive. I started telling myself I was a professional artist before it was true. In high school, I was known as someone who drew, and that helped me connect to other people. I was extremely shy and I was bullied all the time, but if I could make somebody a drawing with their name, it felt like I had power somehow. As far as being confident and telling other people, “I’m an artist,” that was a little after undergrad, when I started having shows.

Is there a meal you eat on repeat when you’re working?

Soup. I love soup. They used to call me Sopita when I was a kid. I’m such a soup head, even in the summer. Hot soup in the summer: Your body gets hot, so any breeze feels excellent.

I love making ramen-style things. I love fish soup with a sancocho broth. Any kind of Caribbean soup. I don’t discriminate, unless it’s tripe. I can’t mess with tripe. It’s too close to flesh.

Are you bingeing any shows right now?

I am. “Obi-Wan [Kenobi]” (2022) and “The Sandman” (2022). I grew up with comic books. That was my thing.

What’s the weirdest object in your studio?

Everything is weird in here. Studios are supposed to be weird.

Rivero, whose studio contains guitars and a drum set, played in bands before deciding to pursue a career in art. Jon Henry

How often do you talk to other artists?

Every day. The majority of my friends are artists, writers and musicians. Many of them aren’t in New York, so I touch base with them, show them the work, see how things are going, hear what their ideas are about it. I feel like the majority of the people I get in here are yes people, and I don’t need cheerleaders right now. I need to know what I’m doing and how it’s resonating with people.

What do you do when you’re procrastinating?

Play music or video games. Or work out. I try to still be productive and have my mind firing off signals somehow. I tend to procrastinate a lot.

What do you usually wear when you work?

I like to wear a uniform. I rotate the same three pairs of pants. They’re the pants I used to wear as a porter. For a shirt, I’ll wear something very factory-worker looking. I want to lose my body a bit. I like to wear things that make me anonymous in my own space. Just custodian clothes. I have a custodian vibe. When I was working in that building, I was a porter, too. Seven years of that. At [David] Zwirner, I was a custodian. After dropping a Henry Darger, although nobody saw, I decided never to be an art handler again. I don’t want that stress. I like the idea of being a super, someone who’s meant to hold on to a space and nurture it.

I was at Zwirner for three years. The first three years I cleaned the gallery, from 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. before they opened. I would just be there by myself. I was the only one allowed in David’s office, and I would do something silly for him every time. I would put all his stuff at an angle, something like that. I like the idea of communicating with people when I’m not there, of having this dialogue through cleaning. The idea of being anonymous helps in terms of not putting myself in the painting too much. I want to be private, and it lets me communicate in these really weird ways. I’ve always kept in my head that I’m still a janitor.

“I might have a color in mind or a combo of colors, and I start from there,” says Rivero about his process. “If I was the kind of artist that sketched things out first, I would love it. It would cut down on so much time. But I get bored.” Jon Henry

What do the windows of your studio look out on?

It’s south-facing, so I get to see the whole landscape of downtown Manhattan, the Triborough [Robert F. Kennedy] Bridge and Governors Island. The roof is amazing, too. You can see Rikers Island.

What do you bulk-buy with most frequency?

Paper towels and paint. I go through a lot of paint.

What’s your worst habit?

Smoking. I’m in the process of quitting; I can do four, five days without it. I did a month recently. It’s the one thing that I hate that I do. What else? Stressing myself out for no reason. I do that really well.

Completed in high school, this work is made of transfers from other paper — “almost like printmaking,” Rivero says. The frame originally held a pastel portrait of his mother, which she hated. When she threw out the portrait, Rivero kept the frame. Jon Henry

What are you reading right now?

“I Know What’s Best for You” (2022). I got really absorbed by that. I’m still reading “Dune” (1965). I love sci-fi — anything that connects to the idea of diaspora, and of people not having a home, being displaced. The hero’s journey is something I’m really interested in.

I’ve also been reading a book by a magician who used to be a card mechanic: “Amoralman: A True Story and Other Lies” (2021). Magic is so related to painting — thinking about your audience, thinking about expectations, how to manipulate somebody’s eye into seeing something. How do you distract somebody? How do you lure them in?

What’s your favorite artwork by someone else?

There’s a forever one: “Gladiators” (1940) by Philip Guston. I’ve stolen so many things from that painting. There’s a little door in the background where you see all these storefronts. It’s half a doorway with these steps going up. That’s one of my favorite paintings — the color, the texture, it’s amazing. For something more contemporary, Chris Ofili’s “Afro Muses” (1995-2005) [series] is something I always think about. I love how he had very specific and limited parameters for making those works: a very loose pencil mark followed by a quick portrait in watercolor, all the same small size. It really taught me the freedom that can come with limited resources or tools.