- Source: Monopol Magazine

- Author: Sebastian Frenzel

- Date: Winter 2018

- Format: PRINT

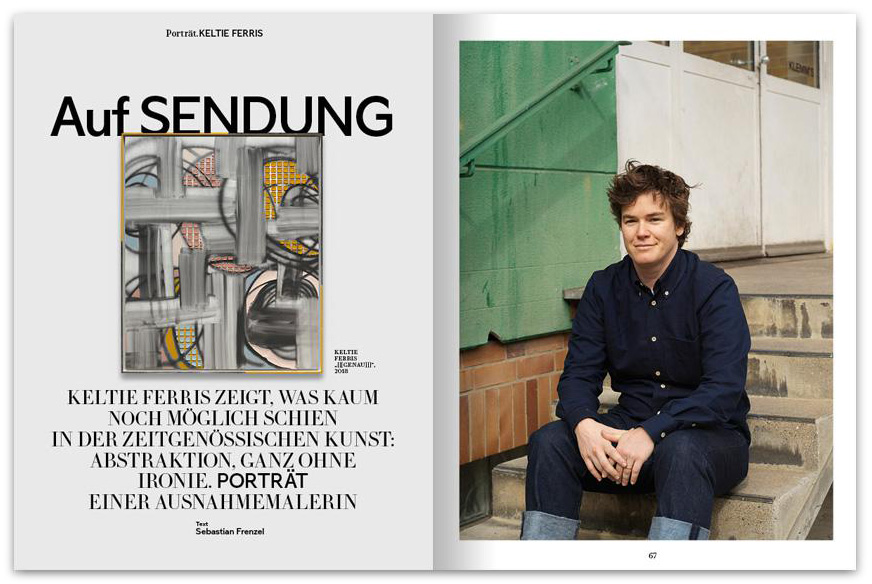

Keltie Ferris shows something that almost seemed no longer possible:

abstraction entirely lacking in irony — a portrait of an exceptional painter

As is true of many good painters, there’s one thing for sure that can be said about her work: it’s damn good painting! But we still find ourselves on the most bizarre terrain. For example, the controversial appointment of Brett Kavanaugh as Supreme Court Justice. Or the question that poses itself for big city dwellers who are no longer so young, but not yet old: whether that was enough city life, whether it might not be better to move to the country. Or the peculiarities of the German language.

The American painter, born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1977, has titled her new exhibition at the Berlin gallery Klemm’s Genau, and she explains that in the following way: “I only speak a little German, but the term seems to mean as much as the English word ‘specific,’ but in the sense of totally. We Americans are always saying ‘totally,’ that came from the West Coast and spread across the entire country and is supposed to sound eccentric. But genau doesn’t sound very hip. It expresses agreement: I am entirely with you! But also a certain sternness.” But even after this brief opening, it should be already be clear; Keltie Ferris goes about the world with her senses wide awake, with a fine sense for nuances and reverberations. She placed three brackets around her exhibition title that emit like radio waves and at the same time seem like the frames that she builds herself for her large format abstract works: [[[Genau]]]. This artist, these paintings are “on the air.” But the affirmative genau or “exactly,” also expresses Ferris’ view of painting. In an entirely non-ironic way, she professes her allegiance to abstract expressionism in the tradition of the New York school. Wholeheartedly and unstrategically, her paintings say “yes” to painting, something that is hardly a given in light of the fact that this old, reactionary medium has been under pressure to justify itself for decades now.

“Higher beings command: paint the upper right corner black!,” Sigmar Polke already made fun of abstraction in the late 1960s. This was followed by decades of good, anti-painting statements by Albert Oehlen or Christopher Wool, Amy Sillman or Kai Althoff. But in recent years in particular, there have increasingly been not such good ones, where you can barely see the art behind all the sarcasm.

Photograph by Einer Ausnahmemalerin

Keltie Ferris has nothing against humor, she just thinks jokes without an element of truth to them aren’t especially funny. And her truth is that she is much too interested in the world to succumb to sarcasm. She prefers to take apparently simple things like the word genau and complicate them until they reveal a higher truth: at the start of her career, when she just moved into her studio in Brooklyn, Keltie Ferris let herself be inspired by New York’s urban space, from the systems and forces that keep city life intact and challenge it. Ribbons made using a spray gun blur in a nervous urban sea, the gestural rebels against order: images full of energy and ecstasy. In the meantime, Ferris is now taking things a bit more easily: she’s had a child with her partner, moved out to the country and turned her back on New York, at least for a while. The painting A to FAR Rockaway, a title that alludes to the subway line that runs from downtown Manhattan all the way out to Rockaway Peninsula on the Atlantic, takes us along to this new world. Heavy shades of blue and purple crash like the waves of the ocean over this large-format abstraction. Shapes emerge, overlap, and cross one another, shapes dissolve. Thickly applied surfaces of paint spill off the image, drawing our gaze back to the depth of the sea, until we find ourselves surfacing somewhere else. “Waves are energy, potential, possibility: and of course they are the most abstract things in the world, and so the subject seems fitting for me as an abstract painter,” according to Keltie Ferris. “I mean, does this image have any relationship to what a wave really is? Or do we just see the effects of a wave? How do we imagine something that we cannot really imagine?”

“I’m interested in things that modernism excluded: graffiti, folk-art, decoration,” according to Ferris. Her paintings combine worlds that are actually irreconcilable. The A-train also links two actually irreconcilable worlds. For naturally there are endless numbers of wave paintings, by the Romantics like William Turner and Caspar David Friedrich or by Claude Monet, but the sea and the sublimity of nature appeared for the last time non-ironically on canvas with post-war abstract expressionism. Ferris takes an earlier point in time as her point of departure, the 1920s. In this period, painters like Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin and Georgia O’Keeffe explored a specifically American version of modernism for the very first time. Inspired by European postimpressionism on the one hand and domestic folk art on the other, they make nature the source of their abstractions. O’Keefe paints her famous flower paintings, Marin is drawn to the raw coasts of Maine, Hartley, after spending many years in Europe, returns to rural New England. In purely abstract forms, they seek to express the essence of the American experience, its vitality, its spirituality. All the while reading the drop out books by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, or Walt Whitman that some escapist hipsters are probably still lugging about with them in their jute bags.

Art history loses sight of the influence of American regionalism on postwar modernism. Clement Greenberg’s ideal of a painting where form is identical to content, or Werner Haftmann’s famous formula of the “universal language of abstraction” propagated the notion of a universalism independent of time and place. In so doing, the colorful gorges of a Clyfford Still Grand Canyon become image, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko are not conceivable without Harley and Dove nor their for nature’s sublime.

Ferris locates her pictures in two spheres: abstract expressionism and folk art, sensuality and concept, city and country. BQE to Flora + Fauna shows a flower in the grass, a motif between Georgia O’Keeffe and the pattern on a bed sheet. Black, sprayed lines result in a drawing-like scaffolding that between which the layers of paint are applied centimeters thick. Ferris colors the interstitial spaces using the exact technique that every art school condemns as children’s or hobby painting. She shrugs at this: “The picture accepts its limitations in the two-dimensional, but not in the three-dimensional.” But almost as if she wanted to counteract this animation, a grid of gray and white blurs rains through the colors, deletes the motif and send us back into the void.

Maybe it’s good that Keltie Ferris grew up in Kentucky in an environment where the profession of a painter was just not an option. “As immigrants, my parents were entirely focused on leading a proper life as a taxpayer, so it seemed to them unethical to want to become an artist.” Ferris started out as a professional field hockey player, also not a job for the long haul. She then decided to become a designer or architect, and visited a painting class as part of her preparation. Even attending art academy seemed to justify herself in her own eyes and in the eyes of those around her: at least you can become a teacher.

It wasn’t until age thirty that Ferris had her first exhibition, and recognition came as a real shock to her. “I thought what I did was really obscure. It was inconceivable to me that somebody else might be interested in it,” she says referring to her paintings. “I still sometimes think today: who painted that? Have I become a florist? As an abstract painter?! I was never tortured by the question ‘Why paint?’ But what I really struggle with is the content. Of course I’m interested in things like the refugee crisis or gaps in income or the appointment of Justice Kavanaugh. As a filmmaker or writer, you can take a position on that directly. But as a painter, the nicest thing is when people see something in your pictures that is something other than what you intended,” according to Keltie Ferris. The “exactly” of painting is placed in three brackets. A stone, that falls into the water, a hole in the matrix, a dance of the molecules, scarcely graspable, already a step further. Story’s Room is a mid-sized picture by Ferris, on which waves in light shades of gray spill over the canvas, reverberating from left to right like sound waves. The picture emerged when Ferris and her partner were waiting for the birth of their child. “Before the baby was born, when we didn’t know what it was going to be, we called our kid ‘Story,’” she explains. But that was only the beginning.