- Source: FLAUNT

- Author: ANDIE EISEN

- Date: FEBRUARY 14, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

KELTIE FERRIS

The rising painter discusses her new work, a busy year ahead, and the realization that the “rarified” art world isn’t impenetrable.

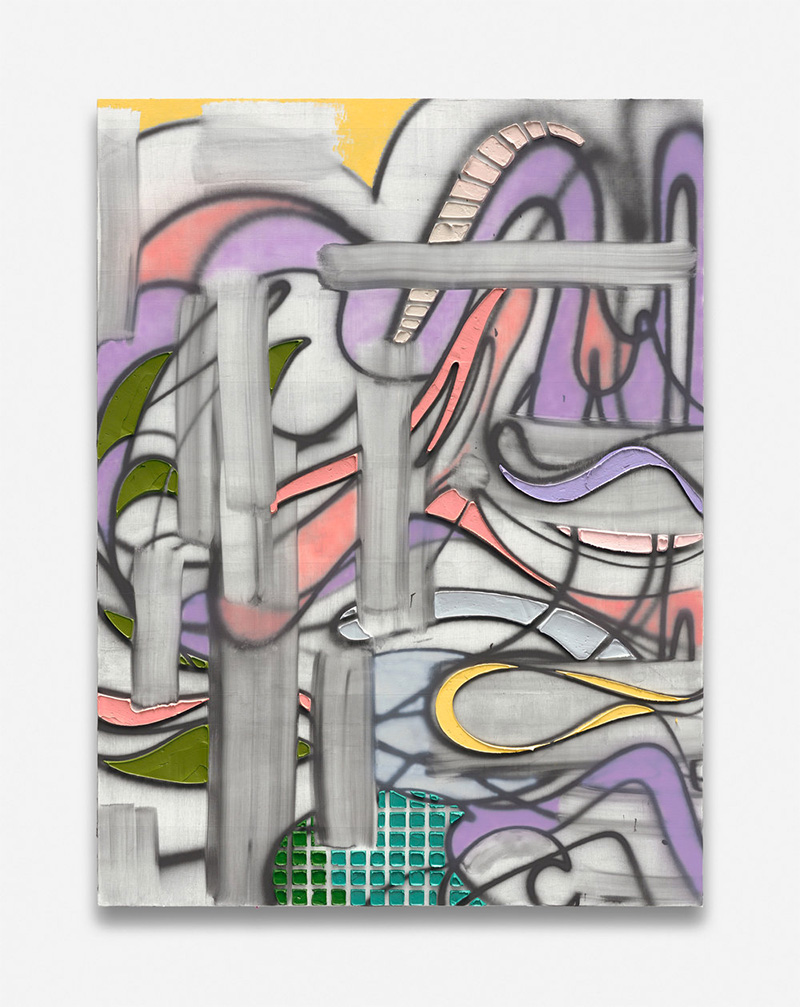

KELTIE FERRIS. “1WAVE1DAY1” (2018). OIL AND ACRYLIC ON CANVAS. TRIPTYCH; EACH PANEL: 80 X 60 IN. © KELTIE FERRIS. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NEW YORK.

“I was making myself some tea, so you might hear me slurping a bit.” Phoning from Woodstock, New York, Keltie Ferris settles into our conversation. I appreciate this detail, remembering a published study from Yale stating that people who held something warm (in this experiment: hot coffee) were more likely to perceive others as “kind, trustworthy and generous,” whereas people holding an iced coffee see others as “distant and selfish.” Emboldened by the good graces secured for me by her beverage choice, I commit the journalistic faux pas of telling her I’ve been a fan of her work for several years. My assumption validated, she gracefully indulges my praise.

In the fall of 2015, myself and my then-partner were bobbing through Chelsea for the perfunctory NYC gallery hop. Driven by that pretentious, guileless swagger of recent art school graduates, we were anxious to consume. Consume what? It’s difficult to explain that insatiable hunger. A hunger for that glimmer of a swoon, that seraphic electricity that certain artworks can inspire—in other words, that bombastic and elusive sense of meaning. My partner, an abstract painter herself and a devout planner, had prepared a hefty itinerary beginning with Ferris’ show at Mitchell-Innes & Nash.

The act of “describing” an abstract painting is almost as obscene as trying to explain why a joke is funny, but I will try to accurately record my impressions from Ferris’ show in 2015. First there’s the scale, something that reproduction in a magazine can’t communicate. In reading Ferris’ previous interviews I often heard her describe the scale of her work as “a stage built just for me.” When I ask her about this nearly 10-year-old metaphor, she says, “It was organizing to have a reason for the scale and to fit it to literally my reach and my body. I come from an athletic background, so making something just a little bit bigger than my full reach just seemed right. It’s as though I’m the actor, and it’s the area that my body needs to make a painting.” With her contemporary work, Ferris’ relationship to the metaphor has shifted. She explains, “More and more now I’m sort of thinking of the painting as the actor. I would even go so far as to say if the painting doesn’t feel active and alive, if it feels passive, then it’s probably just not a good painting.”

KELTIE FERRIS. “STORY’S ROOM” (2018). OIL AND ACRYLIC ON CANVAS IN THE ARTIST’S FRAME. TRIPTYCH; EACH PANEL: 35 X 40 IN. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NEW YORK.

When I saw Ferris’ work for the first time in Chelsea, the paintings were assertively cast as the active participants in the space. The tension between her colors creates shifting optical layers, pushing in and out of the foreground, as if you are racking focus in a pair of binoculars. It is a confident chaos. Fully organized even in its improvisational nature.

I ask Ferris about the atmospheric nature of her work. Is she aiming to express an interior psychological state, or synthesizing something more universal and ‘cosmic?’ She pauses to mull over this clunky question. “They definitely come out of me in a way, but they feel very separate from me. I do see my paintings as expressions of energy and potential. Like a rock teetering at the top of a hill, it has potential energy. There’s nothing more universal and abstract than energy.”

Though Ferris states that her paintings “do not feel like self-portraits,” she has become known for an evocative series in which she covers her body in oil, presses her body directly on the canvas, and renders the print in pigment. She explains, “The body prints partly came out of an intellectual space where I was thinking about indexicality and this conversation around painting as a residue of a human being. That is a very personal residue. The way that handwriting is very personal, and the index of a touch.” When I ask if she views her body as a tool, she concurs, and laughs, “It’s a very limited tool, you can’t really change yourself, you can’t get a different one for a day— with all other painting tools you get them in like five different sizes.” She explains that she divides her body prints into two categories: ones with just her torso, and ones that include her face and hands. The ones with hands and faces, she says, feel more personal, “And so maybe it does become a self-portrait, in a way.”

I tell Ferris about a book I remember reading about surgeons in training. Apparently, for medical students, hands and faces are the most difficult parts of the body to operate on, because they’re too hard to depersonalize. Ferris agrees. “There is something about fingerprints and handprints that’s so charged. Sometimes with the body prints, if there are a lot of hands involved, it comes off very cheesy.” “Like a hand turkey?” I ask. “Yeah! Also like handprints of children when they’re born— fingerprinting has a child aspect and a criminal aspect and it just feels very familiar and not transformative.”

I invoke the 20,000 year-old Lascaux cave paintings. The idea that a handprint represents an innate urge to document the “self.” Ferris affirms: “I mean, 100%. I think it’s so bizarre that I’ve stumbled into the oldest terrain the world.” Discussing Lascaux, I remember that Werner Herzog, in his documentary about Lascaux cave, calls the cave paintings “the first evidence of a human soul.” Inspired by his infamous dramatics, I ask Ferris, “What is that human urge to record oneself? Is it a desire for immortality?” She answers quickly. “Yes. I think of the body prints as useful in that regard, as a practice of acceptance. It’s so insistent, and as I’ve said before, there are these very strict contours and rules that are really pared-down tools and possibilities. It’s kind of a like an ‘acceptance prayer.’”

KELTIE FERRIS. “DRAG TRAP” (2018). OIL AND ACRYLIC ON CANVAS IN THE ARTIST’S FRAME. TRIPTYCH; EACH PANEL: 80 X 60 IN. © KELTIE FERRIS. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MITCHELL-INNES & NASH, NEW YORK.

In her newest series of paintings, which will debut at LA-based gallery Morán Morán this February, she employs a different set of “strict contours and rules.” Using the medium of spray paint, impasto, and linear marks of erasure, Ferris strays from classical conventions of mark-making that one associates with a brush and paint. In the context of the historicity of the medium, I ask Ferris, “What do you feel is the language of these materials?” She takes a moment with this question, prefacing her answer first by saying, “This most recent work is really hard to talk about, and I haven’t really figured out how to talk about it yet.” She continues, starting and stopping as the ideas develop. “I’ve always had those erasures in my work, but they’ve usually gotten covered up. Erasure should be an actor of its own, an active participant. The line work is all curvilinear right now. My previous works have been so much about color and soft edges, so to embrace the classicism of the line has been such scary but exciting terrain for me.” Recalling her training at the Yale graduate painting program, she says, “One way you’re not supposed to make an abstract painting is to make a drawing and then fill it in. That’s not how a serious painting is made. But maybe there’s something interesting there—why are you not supposed to do that? It was really furtive ground, at least for the moment.”

Spending the first 18 years of her life in in Louisville, Kentucky, which she describes as, “a very gentle place,” Ferris took a circuitous path to becoming an exhibiting artist in New York City. “When I moved to New York, I had a lot of jobs making things for other people, a prop shop being one of them.” Before attending Yale, Ferris worked at Izquierdo Prop Studio. “In art school you learn more about, ‘What is art? How does it function in the world?’ But where I learned to actually make something was working for other artists and working at that prop shop.” When I ask her about her favorite props, she laughs. “We just made all kinds of unpredictable things…we made Victoria’s Secret angel wings for the models. The things need to function you know? The wings need to stay on basically a naked woman and can’t show the mechanism of how they stay on. It’s not easy.”

Always a banal question to ask, but one that always feels necessary: Did she always know she wanted to be an artist? Ferris answers, “I thought painting in particular would be something I would pass through because I saw so many other people pass through it, but honestly, I loved it from the very beginning, so I don’t know why I thought that would happen.” I understand the feeling, the way that the world makes art feel like an indulgence, that it’s somehow an unsustainable or self-concerned enterprise, even though it’s what you love most. “Exactly!” Ferris replies. “I really thought that way growing up, that saying ‘I want to be an artist’ was like saying, ‘I want to grow up and be Brad Pitt.’ I thought it was so specific and rarified. We’re fed so much garbage about how only the lucky can do it, so ‘Don’t even think about doing it yourself.’ I didn’t even really know it was something you could do.”

I ask Ferris when she felt she overcame that hesitation, when she realized that being that “rarified artist” was something she could do. It seems she didn’t have to wait too long. “When I was in grad school I was in my first group show, and I was shocked that there was an audience and that people were genuinely receptive and interested. But that was also so idiotic, because I had been looking at art myself. I was part of the audience, but I didn’t respect myself as part of it. I was really an idiot, honestly!” She laughs.

Her anecdote presents an interesting distinction: it wasn’t a lack of confidence but a reversal of roles. I tell her that, in my experience, creative people always underestimate how hungry the population is for something new. It’s not even insecurity— it’s hard for aspiring artists (or writers, or musicians…) to accept that they can be part of the ‘observed’ sphere and not just a part of the ‘observing and digesting’ sphere. She agrees wholeheartedly. “It has been one of the major shocks of adulthood for me. It’s just perverse that I was shocked by it, because I was going to museums and buying art books, you know?” She adds, with a laugh, “I am one of the hungry people.”