- Source: The Brooklyn Rail

- Author: Charlene K. Lau

- Date: December 8, 2021

- Format: Digital

Kandis Williams:

A Line

Kandis Williams’s first solo exhibition in New York, A Line breathes life into Tribeca, inaugurating 52 Walker, the new David Zwirner space directed by Ebony L. Haynes. Taking performance as form and content, Williams interjects Black bodies into the canon of live art, extending multitudinous lineages: classical ballet, modern dance, performance art, and theater. This tidy show of performance on video, Xerox collages, and sculpture (all 2021) plays out like an experiment in choreography; there’s plenty of room for the viewers’ moving bodies, allowing flow and flexibility, crisscrossing the floor, and marking invisible patterns on the gallery floor as dancers might with their footwork. The works exhale in the airy space for living things, which gives the impression of a lofted dance studio, its light and warmth.

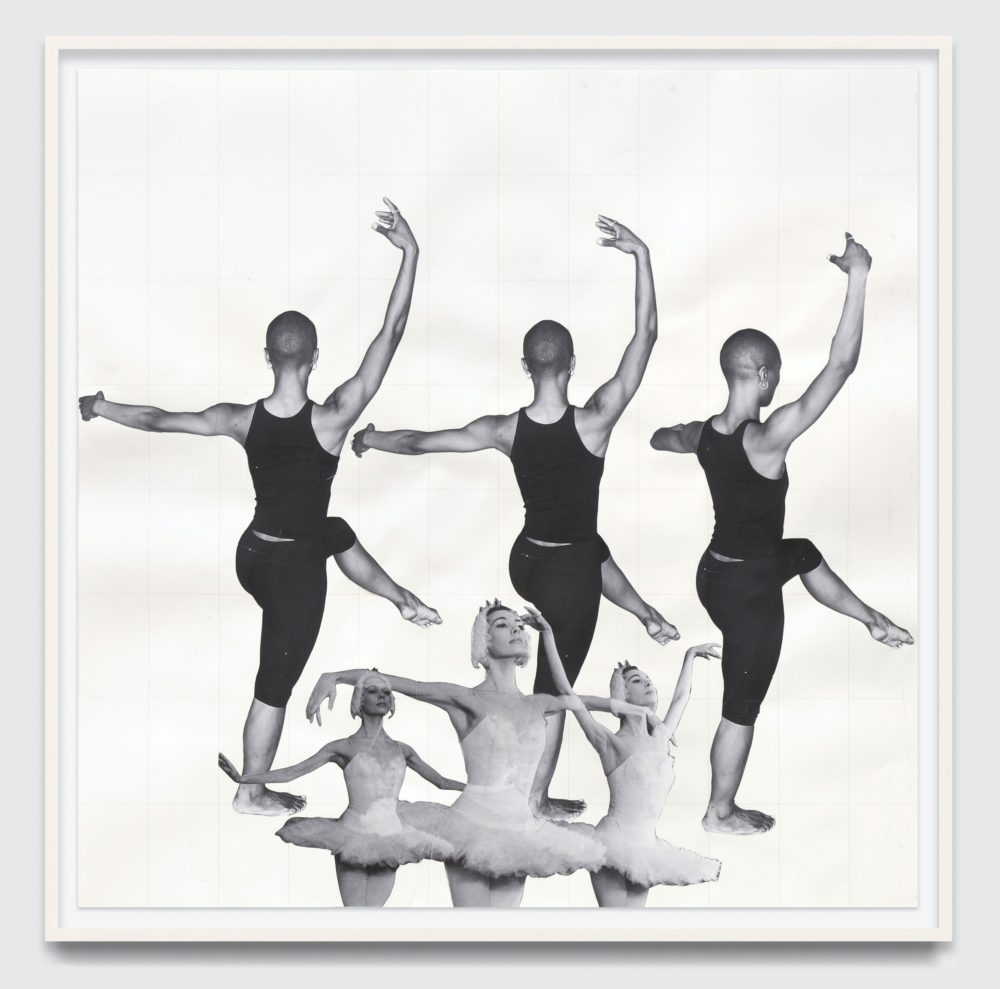

Kandis Williams, Line Intersection Sublimation: Uptown Downtown satisfactions of Swan Lake, east west Pavlova to Mezentseva, Madonna Whore Balanchine to Dunham., 2021. © Kandis Williams. Courtesy the artist and 52 Walker, New York.

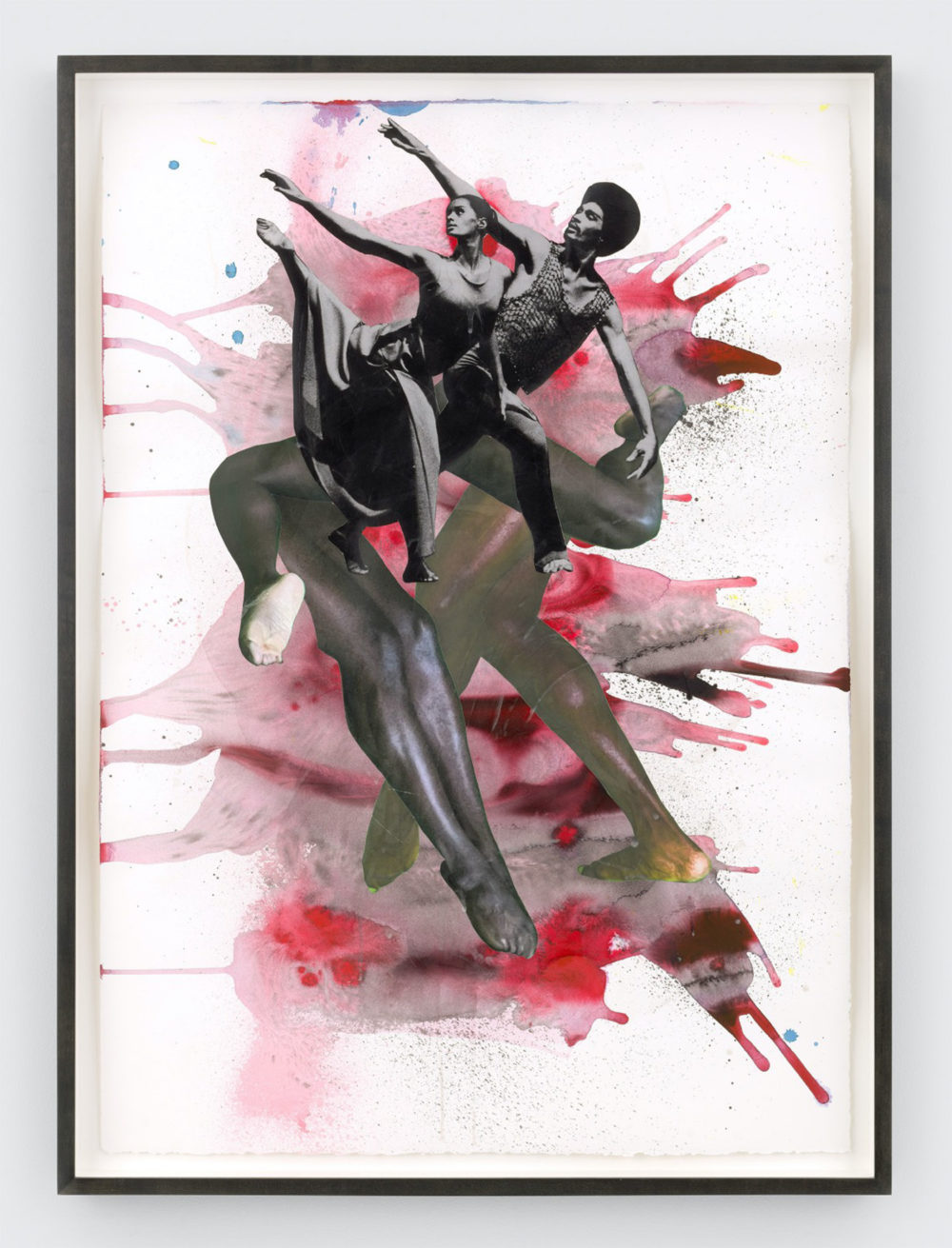

In large-format collage, Williams inscribes gridded paper with cut outs of bodies from the archival material of historic productions and photographs of contemporary dancers taken from her studio. Notes for Stage, Cult, and Popular Entertainment according to place, person, genre, speech, music, and dance depicts the frisson of bodies—including Yoko Ono during her 1964 Cut Piece performance and Merce Cunningham. Art meets athleticism in dance notation form. Crushes of figures from across performance history are depicted all on the same plane atop gestural sweeps of red, blue, and yellow ink. The bodies are full of vitality, but at the same time, their flattening on the two-dimensional surface serves as a metaphor for perceptions and stereotypes of Blackness in culture more widely. Intertwined, their display holds aspects in tension, celebratory yet pressed upon by the weight of history, literally framed and glassed in.

Williams’s extensive titles not only function as descriptions of the works but become their own discreet mini essays, like streams of consciousness, running critical commentaries on the state of Blackness and being within the history of dance. black box, 4 points: Wading in Water, Archipelago, Myth, Revelations—B. Gottschild principle—muffled lines and ruptures—hyper-interpretation of africanist presence(s) is one in a quadrant of collages, and cuts right to scholar and choreographer Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s work on the representation of Blackness in European dance cultures and the avant-garde. Its Expressionistic splashes of red and black ink enmesh complex narratives of beauty and violence, while others from the series present seminal figures in dance: Alvin Ailey and Donald McKayle alongside racist ideologies and Greek mythology.

Kandis Williams, black box, 4 points: Wading in Water, Archipelago, Myth, Revelations- B. Gottschild principle- muffled lines and ruptures- hyper interpretation of africanist presence(s)., 2021. © Kandis Williams. Courtesy the artist and 52 Walker, New York.

Tall, artificial potted plants from the series “Genes, not Genius” flank the gallery, some sidling up to I-beam columns as if figures themselves. Looking closer, they in fact sprout leaves and limbs (images which have been taken from porn) and bear fruits painted the colors of various skin tones, inheritors of the artist’s sculpture series “Fetish Plant” named after her white partners. Avatars for the body, the fruits read as sexual and reproductive, erotic and nourishing. Williams has previously spoken about Black bodies as sites for consumption, both as images and as embodiments of colonial commodities. In “Genes,” Williams conflates anatomy and eros with racial capitalism, as if to emit a toxic off-gas from their seemingly inert, fake, plastic selves.

Kandis Williams, Britannica now: choreography, the art of creating and arranging dances. The word derives from the Greek for “dance” and for “write.” In the 17th and 18th centuries, it did indeed mean the written record of dances. In the 19th and 20th centuries, however, the meaning shifted, inaccurately but universally, while the written record came to be known as dance notation. In biological taxonomy, race is an informal rank in the taxonomic hierarchy for which various definitions exist. Sometimes it is used to denote a level below that of subspecies, while at other times it is used as a synonym for subspecies. A race is a grouping of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into categories generally viewed as distinct by society.[1] The term was first used to refer to speakers of a common language and then to denote national affiliations. By the 17th century the term began to refer to physical (phenotypical) traits. Modern science regards race as a social construct, an identity which is assigned based on rules made by society.[2] While partially based on physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent physical or biological meaning.[1][3][4]Dance notation, the recording of dance movement through the use of written symbols. Dance notation is to dance what musical notation is to music and what the written word is to drama. In dance, notation is the translation of four-dimensional movement (time being the fourth dimension) into signs written on two-dimensional paper. A fifth “dimension”—dynamics, or the quality, texture, and phrasing of movement—should also be considered an integral part of notation, although in most systems it is not., 2021 (detail). © Kandis Williams.

A series of monitors dot the back of the gallery, each playing the single-channel video titled Triadic Ballet, which revisits the Bauhausler and “Master of Form” Oskar Schlemmer’s work of the same name. On screen, a lone dancer moves to choreography informed by numerous traditions including Buffalo dance of Native Americans and jazz. Recent years have seen fresh interpretations of and references to this work including those by Kia LaBeija and Haegue Yang. Like these artists, Williams responds to this history as interlocutor, producing new choreographic narratives that complicate the iconic work’s past within the institution of modern European theater.

On the one hand, the exhibition engages with the politics of showing and displaying performing Black bodies, troubling their roles in performance history against the present day. Where and how do these bodies belong, and with what eyes do viewers gaze at them? On the other hand, it also serves as a record of breath and movement; Williams’s works enact a still and gestural choreography across the exhibition space. They rethink possibilities for how performance can look in the gallery—and therefore history—beyond a display of remnants after a live act that a viewer has almost certainly missed. A different kind of dance emerges, in the air and all around.

Charlene K. Lau is an art historian, critic, and curator who has held fellowships at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, Parsons School of Design, The New School and Performa Biennial. Her writing has been published in Artforum, Atlantic.com, the Brooklyn Rail, Canadian Art, Frieze, Fashion Theory and Journal of Curatorial Studies, among others.